“Has ‘Ringu’ (1998) changed both Japanese and American/western cinema and if so, how?” by Sara Clyndes: Part Two

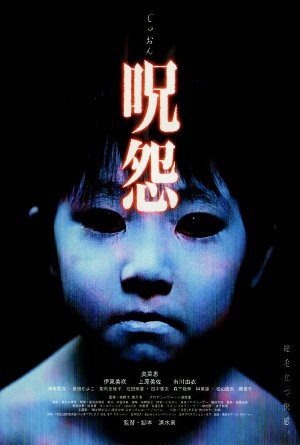

Chapter four – Ju-on: The Grudge

Described by Harper (2008:155) as ‘the most important of the post-Ring horror franchises,’ Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) originally came on the scene in Japanese horror in 2000 as a V-cinema release (straight to video). Its sequel Ju-on 2 was also originally a V-cinema release which arrived in 2000.

After its success on video, Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) was theatrically funded and released into Japanese cinemas. The theatrical release doesn’t really differ from its predecessors; it’s a more technically polished effort and gave Shimizu room to play with his elaborate death scenes.

Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) focuses around a haunted house in Tokyo with an unpleasant past. Kayako (Takako Fuji) and her son (Ryota Koyama) are brutally murdered by Takeo Saeki (Takashi Matsuyama). Takeo (Kayako’s husband and Toshio’s father) discovers his wife is obsessed with a Toshio’s schoolteacher and in a fit of rage murders his family and then proceeds to the teacher’s house where he kills his pregnant wife. Ever since their violent deaths, Kayako and Toshio have remained in the house, tormenting and murdering anyone who dares to enter.

There are a number of different central characters; each segment for them is broken up into about 10-20 minutes of screen time. Their time in the house spans across two decades and they aren’t presented in chronological order. This is also interwoven with Kayako and Toshio’s story and if careful attention isn’t paid it can render the film quite confusing.

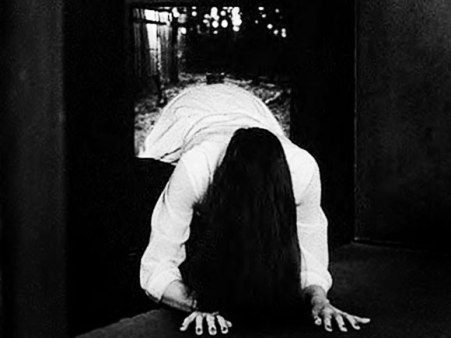

So what makes it stand apart from Ringu (1998)? Well first the similarities need to be noted. The obvious comparison to make is the likeness between Sadako and Kayako. Kayako resembles a traditional Yurei but also has the ‘insect’ like movements of Sadako; her sudden appearances (especially when crawling down the stairs) are very reminiscent of the final scene in Ringu (1998) when Sadako crawls out of the television. According to Harper (2008:157) ‘Shimizu has also learnt some valuable lessons from Nakata about the use of sound as an effective replacement for more expensive special-effects driven scares.’ This most noticeable with Kayako and Toshio – Kayako makes a distinguishing croaking noise when approaching her victims which is extremely unsettling. The croak is due to her throat being slit moments before her death; this was the only sound she could utter. Toshio however, makes a menacing meowing noise (his cat was drowned along with him, this could be a suggestion that they are now some kind of hybrid) and his feet distinctly ‘pitter-patter’ through the house when he is off screen. The other noticeable similarity is the use of technology, it is not as central to the storyline in Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) as it is in Ringu (1998) but it is definitely present. Characters receive phone calls where only Kayako’s croaking can be heard and in one memorable scene the television screen distorts and freezes, deforming the head of the reporter talking on the news.

Whilst there is a definite connection between Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) and Ringu (1998) and Kayako’s frightening presence owes debt to Sadako, this film warrants its own success. It is a significant contributor to J-Horror in its own right, but why?

According to ‘Jay McRoy’ (2005:178) Ju-on: The Grudge’s (2002) success lies in its relationship between U.S. and Japanese horror, ‘Ju-on: The Grudge is a curious filmic hybrid, combining carefully chosen aesthetic trappings of western – particularly US – horror films with visual and narrative tropes long familiar to fans of Japanese horror cinema.’ I agree with this statement, Takashi Shimizu is a self-confessed U.S. horror film fan, especially of the splatter films of the 1980’s. A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and Friday the 13th (1980) are two of Takashi’s personal favourites and have had some cinematic influence in Ju-on: The Grudge (2002). This can be seen in what Carol Clover (1993) describes as the ‘stalker cycle’ which is a narrative trope most associated with the splatter horrors of the 1980’s. Kayako and Toshio, once they have encountered their victim in their home proceed to follow them wherever they go – their menacing presence is always at the forefront of the victim’s life. Combining the visual logics of the ‘stalker cycle’ with narrative tropes of Japanese horror is what McRoy (2005) thinks makes Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) so successful. Although I am in agreement with this I think it goes slightly deeper, more so than just Kayako haunting her victims wherever they go its exactly where she appears that makes the horror of the film so effective. Instead of drawing on folklore Takashi Shimizu brings a pure element of Japanese convention in a U.S. influenced horror by focusing his attention on the traditional Japanese home. Harper (2008:157) cites ‘The director pays close attention to the uniquely Japanese characteristics of the house – the tatami mats, the sliding doors, the family altar, and the closets in particular’. This use of domestic items is very effective, doors sliding by themselves at the end of the corridor, closets shutting and the pitter-patter of feet across the mats makes the atmosphere of the film incredibly tense and uneasy. The house where Kayako and Toshio reside is full of closets, occasionally there is almost a bird’s eye view of the rooms, obscuring the cupboards from view and isolating the audience from the whereabouts of the Onryou. This, however, is not where the true scares lie. Takashi’s use of the traditional Japanese home is in depth and effective but what is most unsettling is the appearance of Kayako outside of the house. In a memorable scene she materialises underneath a character’s bed sheets in which they are currently hiding, this complete invasion into the audiences comfort zone is incredibly disturbing. Richards (2010:79) cites ‘for this writer’s money, Ju-on: The Grudge is flat out the most frightening of all modern J-horrors.’ Another unforgettable scene is Toshio appearing underneath a restaurant table, shattering the illusion of safety in busy public places. Takashi’s effective use of the traditional Japanese home combined with U.S. horror influences and incredible sound production makes this film stand shoulder to shoulder with Ringu (1998) but without Ringu’s success (1998), Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) may have never come to a theatrical release and may to this day have remained one of Japan’s hidden gems.

Chapter five – Ringu’s (1998) impact on the west

Whilst Ringu’s (1998) success in Japan paved the way for the J-horror subgenre to emerge, across the water the west (U.S. in particular) was starting to take notice of the boom that was emerging from the east.

Ringu (1998) and Takashi Miike’s Audition (1999) were screened at the Edinburgh film festival in 2000. Ringu (1998) fared very well whilst Audition (1999) was subject to both praise and negativity, its violent torture scenes caused mass walkout whilst many critics admired Miike’s controversial film (incidentally despite the controversy Audition (1999) went on to have a western theatrical release).

DreamWorks soon acquired the remake rights to Hideo Nakata’s Ringu (1998) and in 2002 Gore Verbinski’s The Ring (2002) was born, sparking off a chain of Asian remakes continuing to this day. The Ring (2002) made $249,000,000 worldwide, over five times more than Nakata’s original. With its success, more Asian remakes started to pour into cinemas, not just from Japan however but also from South Korea and Thailand. To name a few of these remakes: The Grudge (2004), The Eye (2008), A Tale of Two Sisters/The Uninvited (2009), One Missed Call (2008) and Dark Water (2006). It would seem that the impact of Ringu (1998) on western cinema was the sudden influx of Asian remakes. Did these remakes change the face of western cinema? Did they bring forth the crucial elements of a Japanese horror for a western audience to enjoy? It’s hard to see any real impact on the horror genre in the U.S. asides from the influx remakes. They fared well but horror films that followed didn’t seem to take on their conventions. Perhaps this is because as I discussed earlier, it’s hard for an American director to ‘translate’ eastern horror due to its reliability on its own culture and social anxieties. Instead the remakes became westernised and were a far cry from their eastern sources so it would be hard for films that followed to take any real inspiration from the remakes because they’re so diluted from the original. The Ring (2002) didn’t seem to contain many Japanese elements, even the traditional Yurei/Onryou had been moulded from Sadako to the American Samara. Richards (2010:140) argues:

While Asian horror films are content to leave certain mysteries unexplained, or for the narratives and character motivations to retain a core of ambiguity, the remakes tend to add layers of exposition that attempt to rationalise – and thereby contain – their supernatural stories. Nowhere is this more evident than in The Ring.

I share this opinion, the original images that played on the videotape have been changed in the American version and now include a ladder, a tree and a centipede, all of which are now explained one by one throughout the film. The reasoning behind why death occurs after seven days has been rationalised and given explanation, ambiguity was part of what made Ringu (1998) exceptional. However, the biggest variation from the original to the remake is the character of Sadako/Samara. As discussed earlier Sadako is a malicious Onryou, filled with rage and even before her death was suspected of murder. Samara however, is painted in a negative light but with an air of sympathy, she is accused of projecting nightmarish images into people’s minds and allegedly killed her mother’s prize winning stallions but at the same time it seems as if the audience is supposed to have compassion for her. Samara states on a tape how much she loves her mum, the very person who eventually murders her after a life of keeping her locked in a barn. The pure malevolence of Sadako that made her so frightening has gone, leaving a diluted Samara behind.

Although The Ring (2002) and the remake The Grudge (2004) were financially successful worldwide they didn’t eclipse the dark originality of their eastern sources. Although there has been a continuing string of Asian remakes it hasn’t particularly impacted on western cinema as a whole because the eastern conventions portrayed in these remakes were so weak, there was no real inspiration to take from it into other areas of cinema. However, perhaps the real impact of Ringu (1998) in the west wasn’t through remakes themselves but through the accessibility they provided to their source material. Richards (2010:139) claims ‘remakes inevitably raise the international profile of the original eastern horrors, ensuring a greater awareness of the source inspirations and extending their distribution.’ DVD distribution for Japanese horror films went international through the company Tartan Films under the subtitle of ‘Tartan Asia Extreme’. In a survey I conducted, 56 people responded and 70% had never seen an original Japanese horror before the remake. 60% of that 70% proceeded to watch Ringu (1998) after they had watched The Ring (2002). 68% of people in the survey preferred the original to the remake (which interestingly contrasts the ‘Bias Theory’ that whichever version of something similar you see first, you will automatically prefer it). So, through the remakes the west has been opened up to eastern films but going beyond the audience, with the success of Ringu (1998) and its international popularity this gave Japanese directors the platform to break into western cinema. Hideo Nakata took the opportunity to direct The Ring 2 (2005) whilst Takashi Shimizu directed Ju-on: The Grudge’s (2002) international debut The Grudge (2004). Although the many remakes of Japanese films may not have changed western cinema, they definitely made an impact by opening up the ambiguity of eastern cinema to western audiences and created a platform for Japanese directors to have their work recognised internationally.

Chapter six – conclusion

Ringu (1998) certainly made a lasting impression on domestic and international audiences. As well as being the most financially successful horror film in Japan to date it has spawned a lucrative market of merchandise including ‘Sadako’ dolls and collector’s edition DVDs. Ringu’s (1998) popularity was so high in fact that in August (2002) during O-Bon (the festival of the dead) a ‘funeral’ was held for Sadako in Tokyo as the reins of the Ringu franchise was handed over to the west for Sadako to be morphed into Samara. However, did Ringu (1998) change western cinema? The answer is no. The remakes flooded in fast after Ringu’s (1998) release and they were commercially successful but there is little evidence that they (or their originals) influenced films outside of the ‘J-horror remakes’. Instead, they served as a platform for their eastern source material – the west was given a glimpse into an alien culture. Japanese horror was suddenly internationally recognised for the first time since the 1960’s, DVD releases of J-horror and older Japanese films became more readily available. They also served in the favour of directors such as Hideo Nakata and Takashi Shimizu as they made their international directing debut following the success of their films. American remakes were a lucrative but short lived triumph and though they continue the serious contenders in American horror have moved on quite successfully. ‘Found footage’ films such as Paranormal Activity (2007) and The Last Exorcism (2010) currently dominate the western horror cinema. Does Japanese cinema have anymore hope in the western market? I’m sure as soon as a potentially lucrative Japanese film arrives, the west will soon know about it.

Did Ringu (1998) change Japanese cinema? The answer is yes. Ringu (1998) revived the horror genre in Japan – by combining social anxieties of technology, careful pacing of direction and narrative structure and modernising the traditional Yurei, Hideo Nakata created something very special that paved the way for a sub-genre of horror in Japan. Although, with so many films from ‘J-horror’ seeming to rehash the same material, there are some outstanding pieces such as Ju-on: The Grudge (2002) which take some influence from Ringu (1998) and may never have been internationally or perhaps even domestically recognised without the initial success of Ringu (1998). Although the J-horror genre is now in decline Japanese cinema is still going strong with the triumph of films such as Death Note (2006) – there is still much hope for Japanese cinema in the future and it is doubtful that films such as Ringu (1998) will dwindle away in the process.

References

Books

Richards, A. (2010) Asian Horror.

Somerset: Kamera Books

Harper, J. (2008) Flowers From Hell: The Modern Japanese Horror Film.

Hereford: Noir Publishing

Mes, T. And Sharp, J. (2005) The Midnight Eye Guide To New Japanese Film. (2nd edn).

California, U.S.A: Stone Bridge Press

McRoy, J. (ed.) Japanese Horror Cinema.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Goto-Jones, C. (2009) Modern Japan: A Very Short Introduction.

New York, U.S.A: Oxford University Press

Balmain, C. (2008) Introduction to Japanese Horror.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Suzuki, K. (2005) Ring.

Glasgow: Harper Collins.

Suzuki, K. (1992) Ringu.

Tokyo: Publisher Unknown

Clover, C. (1993) Men, Women and Chain Saws: Gender in Modern Horror Film.

U.S.A: Princeton University Press

Websites

(1997) Ringu. Available at:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0178868/ (Accessed Nov 27th 2011)

(2001) Ju-on: The Grudge. Available at:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0364385/ (Accessed Nov 27th 2011)

(2001) The Ring. Available at:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0298130/ (Accessed Nov 27th 2011)

(2003) The Grudge. Available at:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0391198/ (Accessed Nov 27th 2011)

(1995) Ghost Actress. Available at:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0229499/ (Accessed Nov 27th 2011)

(1990) Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Available at:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0072271/ (Accessed Nov 28th 2011)

By Sara Clyndes

Be the first to comment