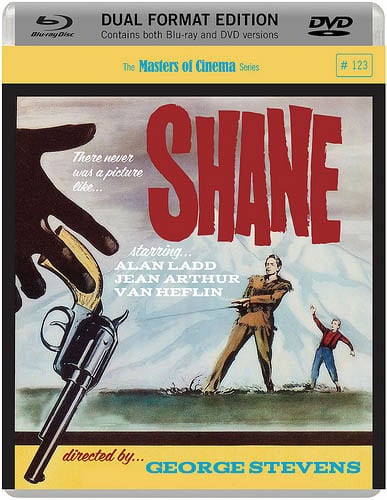

Shane (1953)

Directed by: George Stevens

Written by: A.B. Guthrie Jr., Jack Schaefer, Jack Sher

Starring: Alan Ladd, Brandon De Wilde, Jean Arthur, Van Heflin

USA

ON DUAL FORMAT BLU-RAY AND DVD: NOW, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 118 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Shane, a skilled gunslinger with a mysterious past, rides out of the desert and into an isolated valley in Wyoming. At dinner with a pioneer homesteader, Joe Starrett and his wife, Marian, he learns that a war of intimidation is being waged on the valley’s homesteaders. The ruthless cattle baron Rufus Ryker is trying to run them out and seize their land. Starrett offers Shane a job, and he accepts, but soon encounters Ryker’s men who are out to cause trouble, while Starrett’s young son is, against his mother’s wishes, drawn to Shane and his gun….

Shane, a film that has not only inspired countless films but has virtually been remade as Knives Of The Avenger, Steel Dawn, Drive [yes, the superb Ryan Gosling starrer] and probably others, is often regarded as one of the greatest westerns ever made, though it took me a long time to come around to that way of thinking. As a teenager I found it too slow [three fifths of the film before a single gun shot!? In a western!?], talky, restrained [if the hero and the heroine aren’t going to kiss, at least let them tell each other how they feel, Jesus!] and actually inferior to Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider, which I’d seen not long before, and which was a semi-remake of Shane with a bit of Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter thrown in there too. Of course, like all great movies [Citizen Kane followed a similar pattern for me], it got better with successive viewings, though last night was the first time I’d seen Shane in a couple of decades. And it was almost a revelation. I guess I just had to be of a certain age to really appreciate it. It’s not supposed to be about guns blazing [in fact, though I know others would disagree, it came across to me as an anti-violence western much like Unforgiven]; instead, it’s about integrity [but not in a simplistic way] and inter-personal relationships, and is a very sad story of a violent man who just can’t settle down and escape who he is, something often depicted in westerns but not as well as in this one. It’s also a highly subtle film, where a glance or a line can be all we are told about something or someone; I tried to ‘work out’ its enigmatic hero throughout, and discovered a mess of contradictions and a psychological mess. And it’s brilliantly pictorial throughout, with every shot superbly composed. Yep, it’s a classic which deserves its reputation, but to first time viewers I do say don’t expect a typical western, despite it being packed with what were already archetypal characters and situations.

It was based on a novel written in 1949 of the same title by Jack Schaefer. A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s screenplay, which was augmented by additional dialogue by Jack Sher, was fairly close to it, though it changed some names and made some details more ambiguous and less ‘spelt out’. Director George Steven originally cast Montgomery Clift as Shane and William Holden as Joe Starrett; when they both proved unavailable, the film was nearly abandoned. In a rare case of a female lead being older than the two male leads, 52-year old Jean Arthur was coaxed out of retirement to play Marian Starrett. Shot mostly on location near the Grand Teton mountains in Wyoming, the film was made with meticulous care, Stevens even importing scrawny-looking cattle because the local herds looked too well-fed and healthy. Jack Palance was scared of horses and a scene of him mounting his steed was actually a shot of him dismounting but played in reverse, while the original planned introduction of his character galloping into town was replaced with him on his horse with it simply walking. Stevens shot scenes from multiple angles and, although the film was made between July and October 1951, it was not released until 1953 due to his extensive editing. By then, the industry’s conversion to widescreen had began and Shane was often shown in a ‘matted’ version that mis-framed Stevens’ meticulous compositions. Paramount had little faith in it and almost sold it to Howard Hughes but it became a major success.

Shane is introduced to us riding through the wilderness. A young boy, slogging around in a marsh, aims his toy gun on a deer grazing on some grass stems. The deer lifts its antlers and perfectly frames a lone rider approaching in the distance in a quite brilliant introduction to the character. The lean handsome stranger takes time to address the boy as though he’s someone worth talking to: “You were watching me down the trail quite a spell, weren’t you. I like a man who watches things going around….He can make his mark someday.” The boy smiles up at him, and an instant bond is formed. In fact, the heart of the film is Shane’s relationships with two people. One is with the boy Joey, who thinks he’s a god and whom he wants to be like, though the film takes the trouble to question whether a guy like Shane and his lifestyle are worth worshipping at all. The other is with his mother Marian. She’s clearly attracted to the bad boy, and he feels something for her, but all that results is lots of furtive glancing, often when the other isn’t watching, and the odd indirect line. When she sees Shane standing in the rain in an early scene, their looks are enough to convey what they are feeling and the chemistry between Alan Ladd and Jean Arthur is simple extraordinary. Shane’s departure at the end [come on, this is hardly a spoiler!] could not just be because he can never settle down and be what he isn’t, but because he’s fallen in love but realises he’s the wrong kind of man for a woman like her, though why do I get the feeling that this has happened to him before?

The main external conflict in the film is between cattlemen and homesteaders, a conflict that also provided the basis for Heaven’s Gate and many others. The cattlemen, folk who first tamed the land [i.e. took it from the natives], resent the settlers, and are not just depicted as heartless villains. Shane clearly doesn’t want to fight anybody and walks out from the first confrontation. An epic bar brawl results in the second, with Shane besting one bad guy and then having to be rescued [or does he?] by Joe. But Shane does not use his gun, aside from training Joey how to shoot [which, again, is not depicted totally positively], until near the end. We do get one shooting before though, a quite shocking [partly due to the incredibly loud sound effect, which may actually make you jump and was in real life a cannon being fired!] when villainous gunfighter Jack Wilson guns down a guy in what chillingly comes across more as more of an execution more than anything else. Shane was the beginning of a more realistic approach to violence in the western, though the idea wouldn’t be significantly carried further for over a decade. Of course there is a final showdown, but little sense of release or even victory. The Starrett’s may now be able to carry on peacefully with their lives, but Shane has gone and ‘done it’ again. We’re left the feeling that he could be going from place to place, trying to become a better person and settle down, and failing every time. Violence isn’t necessarily the answer [we almost side with the settlers who leave, they seem sensible], the key line being:“There’s no living with a killing. There’s no going back from it. Right or wrong, it’s a brand, a brand that sticks”. When Joey cries “BANG BANG BANG BANG” as he brandishes his toy rifle, he may think lots of shooting is cool, but the film tells us that it isn’t at all.

While there is quite a bit of chat in the movie, and, I must admit, not all it essential, there are so many great details everywhere [keep an eye on the dog], while many of the key moments in the film just consist of looks, like when Shane looks at Marian and Joe dancing, his face just revealing his sadness at a life he cannot have, and when, later on in the same scene, Joe looks at Shane and Marian dancing, first with happiness, than with sadness. Stevens does pace the film quite slowly, the camera often choosing to linger, for example, on silhouettes of people at a funeral. Mountains are constantly in the background, dwarfing the humans and showing their isolation in this beautiful but desolate landscape. Cinematographer Loyal Griggs gives us beautiful, studied shot after beautiful, studied shot, usually with long lenses, but the visuals – and indeed the whole mood of the film – turn dark around two thirds of the way through when most of the subsequent action takes place at night time. When Shane and Joe fight, chiefly because the former is trying to stop the latter going off to fight [though we know there are other, almost subliminal reasons too], it’s staged in a manner approaching the Gothic, while I can’t be the only one to wonder if we’re being led to believe [look at the two usages of a cemetery] that Shane is not long for this world.

Then again, I couldn’t stop wondering about Shane himself, a kind of western samurai with his own moral code, but a guy who actually seems to be incredibly insecure. I’m not even sure if he does what he does because he thinks he’s doing the right thing. Short, even unassuming Ladd, who is brilliant throughout, hints at so much, and yet gives away so little. Meanwhile Palance’s laconic psychopathic Wilson, who dresses in black and even drinks black coffee from a black cup, embodies the nastier side of the coin. He doesn’t really have any depth, but why should he? Young Brandon De Wilde almost drove me mad with his constant utterances of “Shane, Shane”, but he does transmit hero adoration very movingly. Victor Young’s score expertly combines lovely nostalgic Americana with more dramatic and astringent work, perfectly encapsulating the film’s view of the Old West. Shane is one of those films that can be not only be classed as a near-perfect melding of artistic endeavor and commercial venture, but can also, though it’s probably an over-used term, rightly be termed ‘deceptively simple’, being very straightforward on the surface but more complex and fascinating the more you get into it, and with a genuine sense of myth-building at its core. And, come the end, it’s genuinely heartbreaking. If this is the first time you’ve seen it, I guarantee that you won’t get the words: “Shane. Shane. Come back! Bye, Shane” out of your head. It almost chokes me up now just thinking about it.

Rating:

Eureka Entertainment’s limited edition Blu-ray looks superb with maximum quality sharpness, density and colours, though it does make the scenes in the film which were shot ‘day for night’ more obvious. Blacks and whites seemed especially impressive to me. The set presents Shane in three versions; the original intended print, the cropped, wider theatrical print, and a slightly different theatrical print cropped differently. I checked them all out and they all look good in different ways but it’s the intended 1.37 version that I’ll most return to in future. The sound isn’t quite so good as the picture, some dialogue being hard to make out, though considering the film’s age it’s still perfectly reasonable overall. The special features port over a rather dry but still hugely informative commentary from a DVD release and adds a talk about the film and its director which I just wish was longer, plus a radio adaptation with Ladd and Van Heflin reprising their roles.

SPECIAL FEATURES

*Limited edition two Blu-ray set 92000 copies]

*Stunning high-definition restoration in three aspect ratios

*Disc One – The intended 1.37:1 presentation

*Disc Two – The 1.66:1 original theatrical presentation AND an alternate 1.66:1 framing optimised for this ratio, supervised by George Stevens, Jr [Ltd edition exclusive]

*Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard-of-hearing

*Uncompressed mono and stereo soundtracks

*Audio commentary by George Stevens, Jr. and associate producer Ivan Moffat

*Video interview with film scholar Neil Sinyard

*Complete Lux Radio Theater adaptation of Shane

*Original theatrical trailer

*36-PAGE BOOKLET featuring writing on the film by Penelope Huston, a previously unpublished interview with Stevens, a treatment for an unfilmed prologue to the film, essay on the different ratios, and archival imagery

Another great review from this brilliant reviewer. In fact, it’s probably one of the best written reviews I’ve ever read.