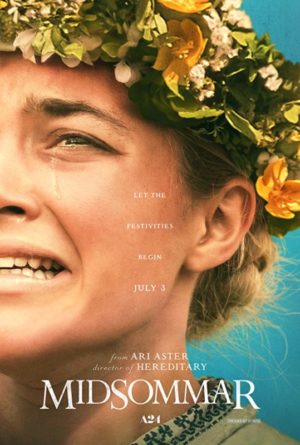

Midsommar (2019)

Directed by: Ari Aster

Written by: Ari Aster

Starring: Florence Pugh, Jack Reynor, Vilhelm Blomgren, William Jackson Harper

MIDSOMMAR (2019)

Directed by Ari Aster

This review contains mild spoilers

In writing for this site, you can guess I love horror and cult films alike. So you can bet I’m partial to horror films about cults. From classics such as The Wicker Man and The Devil Rides Out, to recent efforts like Apostle, The Sacrament, The Witch, The Endless, and indeed Hereditary, plenty of scary films have had sects. Yet few have excited me as much as Midsommar – the second movie from Ari Aster: the visionary writer/ director behind the afore-mentioned Hereditary. Like Jordan Peele, he’s back this year for the tricky second film, after the runaway commercial and critical success of his debut made him one to watch. And also as per Peele, he’s gone for a more complex film that takes risks – although he does so arguably less successfully.

The first thing that jumps out is this isn’t too big a departure. It may be exaggerating to call Midsommar a spiritual sequel, yet it begins with a similarly blunt depiction of grief. Dani (Pugh) is distraught, following a family tragedy. Her suffering prompts her reluctant, and confrontation-allergic, boyfriend Christian (Reynor) to stay with her some more out of pity. This is also why he invites her on a boy’s trip to Sweden he has planned with anthropologist buddies Josh (Jackson Harper), Mark (Poulter) and Pelle (Blomgren). It’s the babyfaced Scandinavian Pelle’s kooky family they intend to stay with, in a picturesque pagan commune far from the nearest Ikea, for a once-in-a-lifetime midsummer festival. It’s a beautiful location, actually shot in Hungary, where there are beautiful green plains surrounded by lush forests and lakes. Combined with the constant daylight, numerous odd concoctions and peculiar rituals, this makes for a trip like nothing they’ve experienced before. Or, being American tourists in a horror film, like nothing they will necessarily live long enough to experience again.

Since his debut short The Strange Thing About the Johnsons, that was about a boy who routinely molests his own dad, Aster has enjoyed making his audience as uncomfortable with sudden bouts of gore or dysfunctional families. Regarding the former, Midsommar is no exception, with the tranquillity being repeatedly punctured by an underlying threat or a nasty image. More so than any unseen twists or turns in the plot, this is the movie’s main bait and switch. But with the latter, what’s interesting is the commune family are probably Aster’s least dysfunctional. They gladly share in each other’s pain and joy alike. Relationships come and go, yet theirs is a society built upon unconditional love and acceptance for one another. Dani goes with the intention of escaping the isolation of a society in which she grieves alone. The contrast between this and an actual community, where people are not just allowed to let it all out but are actively encouraged to is interesting. Moreover, the cult doesn’t just give people a space to express their emotions. They are also willing to share them in what I would regard as the film’s most powerful moments.

However, the intimacy of these scenes is undermined by the storytelling, since the violence and deceitfulness of the cult legitimise the casual xenophobia and dismissiveness of the Americans – think Hostel, but way less obviously satirical. Ignorant outsiders not fitting in with foreign customs is an established trope. Though given most of what we see of this culture seems reduced to being as strange or brutal as possible, it misses the mark if the intention is to critique reactionary attitudes by ostensibly justifying them. I say assuming audience members won’t buy parallels between killing elders and putting them in a home as being mere cultural differences. There a similarly mishandled attempt at laying out a moral relativism, given the temptations of the environment are used to lay bare the sins of the Americans. But this is also undermined by the fairly direct manipulations employed by the cult to get them to where the story wants them. I expect this aspect of the story sounds familiar. As per the possession subgenre, it’s hard for folk-horror films to leave the shadow of the first really good one that established much of the template and cinematic language. Aster has recently said he tried to avoid allusions to The Wicker Man. Yet its flaming effigy stands high over much of the second half, with a lot of the iconography and the structure feeling borrowed.

Not that I think audiences will need to have seen that film to see where Midsommar is going from very early on in it since it is essentially a mystery without any mystery. Hereditary played with the idea of inevitability but did so without lapsing into predictability. How it changed focal point three times felt fresh, and though the signs for where the plot would ultimately go were there the specific character journeys were unexpected. In contrast, the events of Midommar’s third act are so telegraphed it feels gratuitous watching the characters miss the signs for most of the excessive 2.5 hours running time. The characters aren’t just dim either – they’re boring. Florence Pugh is exceptional in the part of an emotionally fragile young woman who only finds her voice in the movie’s many guttural screams. However, she makes for a very passive protagonist who is seldom characterised beyond her grief. She’s a far cry from the rich material the similarly astounding Toni Collette had to work with for Hereditary, which makes Pugh’s performance a real achievement. Her companions are similarly sketchy, with each being reduced to a vice such as academic curiosity or lust. And while act 1 is an emotional, realistic and darkly funny look at a relationship everyone knows should end, this strand doesn’t have an especially satisfying climax. Given Aster describes this as a “breakup” movie, it has unexpectedly shallow character dynamics – with the main cast reduced to conduits for us to witness the odd rituals in the second half.

Despite all these misgivings with the storytelling, I’d actually still recommend you see it – and on a very big screen. Because as a technical piece, it is excellent. The sets are gorgeous, with lots of lovingly handcrafted details. Aster maybe relies too heavily on long Steadicam shots, though they add to the ambient otherworld nature immensely, and allow for an immersive experience as we explore with Dani. The sound design is fantastic too. Though the soundtrack is a bit hand-holdy, in telling us what to feel, it still gets below the skin early on and never leaves. Some bits of Midsommar revel in pastoral beauty, as the trees around the village breathe in and out in a hallucinogenic haze. But below the traditionally safe blue, sunlit skies is a real air of menace. There are also individually shocking images laced throughout that Aster doesn’t shy away from. Instead, he uses them to confront the viewer on the cost of this way of life. When considered alongside the delayed, linear storytelling he makes viewers almost complicit in the onscreen carnage, that’s by now as much a genre ritual as a religious one. But audiences are not just implicated in this, since they are likewise invited to join in the sheer awe-inspiring energy of the dance and ceremonial scenes. The scale is often remarkable, with the bloody carnival atmosphere building to an operatic crescendo after we reach the crowning of the May Queen (that for some reason happens in June). I wasn’t especially moved, or even very interested in what happened to the characters. But darn it, was I impressed! It’s a dreamlike, sensory experience that captures the contagious joy of sects.

Rating:

Be the first to comment