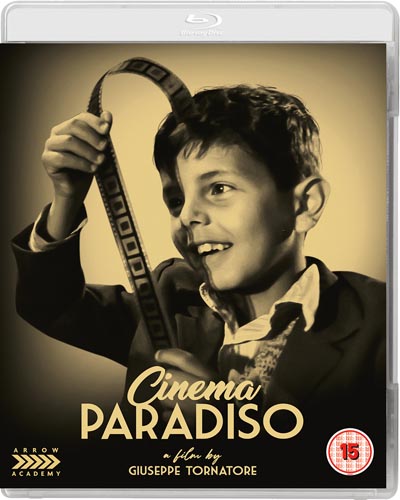

Cinema Paradiso (1989)

Directed by: Giuseppe Tornatore

Written by: Giuseppe Tornatore

Starring: Jacques Perrin, Marco Leonardi, Philippe Noiret, Salvatore Cascio

ITALY/FRANCE

AVAILABLE ON UHD BLU-RAY: 7TH DECEMBER 2020, from ARROW ACADEMY

RUNNING TIME: 124 mins/ 174 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

In Rome, famous film director Salvatore Di Vita learns that “someone died, someone named Alfredo”. He flashes back to when he lived in the Sicilian town of Giancaldo, a place he hasn’t visited in thirty years. The eight-year-old Salvatore was the mischievous but intelligent son of a war widow. Nicknamed Toto, he discovered a love for films and spent every free moment at the Cinema Paradiso where the projectionist, Alfredo, often let him watch movies from the projection booth. Toto and Alfredo formed a bond. But eventually tragedy struck – and then Alfredo fell in love…

Long-time readers of this website may have come across me extolling the virtues of writer/director Giuseppe Tornatore [if you’ve never seen them, may I especially recommend Deception aka The Best Offer, Everybody’s Fine, Malena and The Unknown Woman] who for me is one of today’s finest directors even though he’s never matched the commercial success he achieved outside Italy with Cinema Paradiso in 1989. And, while his knack for thinking up and telling highly emotive, wistful and meaningful stories has certainly served him well artistically and in his native country even if I get the sense that he’s sadly not relevant in today’s cinematic climate [if he’d been making films several decades before he’d now be widely regarded as one of the great auteurs], there’s no doubt that Cinema Paradiso, in whatever version [its two main versions are very different to the extent of hugely altering one major character and changing the tone], is an absolutely wonderful movie, and one that’s understandably a favourite of many film-lovers, largely because, while it also looks at love for a friend and romantic love [the latter more so in the 174 minute version], more than anything else it’s a love letter to cinema, and going to the cinema, especially old style picture houses which were dying out even then. These were places where the cinema was not just for passive entertainment but was the centre of life, where people escape, cry, laugh, quarrel, learn, drink, whistle, screw, fall in love – in short, they live.

It was Tornatore’s second feature after the gangster saga The Professor which failed to make much of an impression, though he got the idea way back in 1977 when he worked as a projectionist at an old cinema. It closed and the owner decided to sell the building. Tornatore had to help clear everything out and clean the place, and the sad atmosphere inspired him to create the basic story which he added to over the next ten years, talking to many projectionists for inspiration. He wanted Marcelo Mastroianni to play Alfredo, but was overruled by producer Franco Cristaldi. For little Toto, he photographed over 300 Sicilian boys before he cast Salvatore Cascio. He had trouble finding someone to play middle-aged Salvatore, and shooting even began before he asked Jacques Perrin out of desperation even though he didn’t look much like Cascio or Marco Leonardi [teenage Salvatore]. He was unable to use a tiny clip of Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth kissing because it would have cost $700 000. A 174 minute cut premiered at the Europa Film Festival in Buri to such a good response that distributors Titanus thought it wouldn’t need much promotion. Tornatore cut it down to 155 minutes but it flopped in Italy, so he reduced it to 124 minutes – and it flopped again! Fortunately a showing at the Cannes Film Festival caused a sensation, leading to worldwide success and winning the 1990 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The 174 minute version was released in some countries in 1994 [though it took nearly another decade for it to reach the US]. It’s the 124 minute cut which got the 4k restoration this year for cinemas and then this UHD release, so I’m basing the larger part of my review on that; however, I will also look at the longer cut after.

While we begin in the house of Salvatore’s mother [ it’s odd that one of the very few bits in the film that Salvatore isn’t present at begins it], most of the film comprises of extended flashbacks as Salvatore hears the fateful news that Alfredo has died. He lives in this big house so we know that he’s rich and successful, yet the large rooms have a feeling of emptiness, the blue lighting a sense of coldness. His somewhat younger bed companion seems to be the latest in a long line of casual relationships. He hasn’t been to his home town of Giancaldo in over 30 years and one asks why? In an artform littered with great segues from present to past, the first one here is simple yet perfect, the sound of chimes bringing on a cut from Salvatore’s face to the top corner of a church, the camera slowly panning down towards a small boy in front of an altar holding a little bell. The boy is, of course, young Salvatore aka Toto, and Father Adelphio needs him to be on the ball with the bell because otherwise he’ll lose his place giving mass, but Toto is half-asleep. Told off, Toto’s reply indicates that his family is so poor that they don’t always eat enough, which is why he’s so tired. The dose of reality about poverty is actually unusual in what is otherwise a very rose-tinted view of the past, even if set in a place where life would be hard, but that’s exactly the point – Salvatore’s memories of his much younger days probably would be rose-tinted. Therefore our impression of Giancaldo, a fictional place which is in reality a combination of three locales – Bagheria, Cefalu and Palazzo Adriano where they built the cinema in the town square – is nearly all positive.

I’m not the biggest fan of cute moppets on screen, but I always adore little Salvatore Cascio from his very first appearance; he has the most infectious smile ever and therefore we feel his joy at being allowed into the projection booth, at viewing footage that patrons of the cinema will not be allowed to see, at being able to ride on the same bicycle as Alfredo after he’s feigned pain so he doesn’t have to walk home with everyone else. Alfredo is almost saintly – but that’s how he would be, because he was the person that Toto worshiped – and still does. Toto’s father went off to fight and hasn’t come back; his mother struggles with this and her relationship with her son isn’t warm. She dislikes Toto’s obsession, “movies, that’s all he talks about, Alfredo and movies”. So Toto sees Alfredo as a surrogate father, while the affection that he should get from his mother he instead gets from cinema. And he’s privileged; not only does Alfredo often [if sometimes begrudgingly] let him come up to the projection booth, he lets him see the films being ran through the projector uncensored for Adelphio. Kisses aren’t allowed, so Adelphio has to see the full movies on his own and ring his bell whenever he needs a bit to be cut – though sometimes he gets carried away by what he’s watching and almost forgets to do his job. He pulls faces and seems a bit exaggerated much like many of the other characters, just as they would be from the point of view of both a child and an adult remembering them; another good example is the town lunatic who always has the opposite view to others, to the point of being the only one pleased when a terrible disaster befalls the cinema.

The cinema is where it all happens. Two patrons fall in love at first sight when they’re the only ones not cowering in fear from Spencer Tracy in Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde. One guy goes there just to sleep but always gets rude awakenings. Another sits with the other upper class types in the balcony and spits on the lower orders, a bit of straight-to-the-point class commentary there. A couple even have sex and either nobody notices or they don’t care. Cinema Paradiso is generally known as a highly sentimental effort, but it’s also darn funny, from Toto trying to help his dim classmate Boccio with maths and getting him into even more trouble, to the local gang boss getting shot dead in the cinema at the exact point a gun is fired on screen and his coffin subsequently taking up his seat. Teenage boys sit in the front row doing what many teenage boys would be doing when Bridget Bardot was onscreen. The usher tells them off [“look, don’t do”], before glancing at the screen and giving his own flies a little tweak. However, Tornatore stops just short of mocking his salt-of-the-earth peasants whom he clearly loves – even when they don’t understand a Michelangelo Antonioni film. The chronology seems to be accurate with one glaring exception where a movie is shown several years too early. Does it matter? Not really, in fact I’m surprised that there aren’t more inaccuracies seeing as this isn’t, and shouldn’t be, precisely realistic anyway.

Alfredo loves Toto like both a son and a best friend despite their age gap, but doesn’t want him to live the hard life of a projectionist. But events result in him becoming one anyway, though Alfredo is still around to dispense life ‘wisdom’, albeit life wisdom which often takes the form of quotations from movies. After an hour, the film moves into its slightly shorter second phase where we transition to the teenage Salvatore. The laughs still come, but the tone is rightly less playful. Salvatore falls in love with a girl from a rich family, and maybe this is slightly less magical than what’s come before because we’ve all seen lots of stories of a similar kind told on screen, while Salvatore waiting outside Elena’s house day after day for her to respond would probably be considered as stalking if the film were made in today’s climate. Some cliches are relied upon, but this is appropriate seeing how this romance is something that Salvatore still idealises. The kisses of these two are so full of longing, while when one of the greatest love themes of all time [not actually by score composer Ennio Morricone but his son Andrea] plays over them, its repeated melody seeming to reach further heights of passion as each repetition has a fuller orchestration than the one before it, a perfect musical representation of Salvatore’s amour fou. Salvatore is destined to find out that the happy endings of on-screen lovers don’t always match reality. As Alfredo tells him, “life is not what you see in film. life is much harder”.

But there’s still the cinema, where one can escape for a bit; to us movie freaks, is there anything more comforting then when those lights dim? The Giancaldo crowd collectively weep during Anna and are in hysterics during Il pompeiri di Viggi [The Firemen Of Viggiu], which outside of Italy is a largely unknown comedy starring comedian Toto. When it’s shown, we get the first of the two truly magical scenes that take place in this movie; it’s full of lovely moments, but two are just insanely wondrous. Because people are almost breaking the doors down to see the film which is showing inside, Alfredo has an idea to resolve the problem. Realising that he can reflect the movie out of the window in his booth, he causes it to appear before the very eyes of the folk outside, moving before alighting on the front of a house. For sheer wonder, this moment is hard to beat, and we’re also reminded of how movies may have got bigger but the screens didn’t keep pace with them; in fact they mostly got smaller. In fact progress is depicted as not always a good thing. Just look how unsightly Giancaldo looks in the 1988-set scenes, with cars and advertisements everywhere. The coda of middle-aged Salvatore returning to where he grew up is thick with nostalgia, the pace slowing down greatly; but that’s fine, it’s now time to reflect, and one cannot help but be deeply moved even before we get to that finale, a finale I won’t describe just in case you haven’t yet had the pleasure of seeing Cinema Paradiso, but a finale which neatly brings things full circle and has the power to create a lump in the throat in the most hardened of viewers, while at the same time probably causing different intellectual responses. It’s one of the greatest film endings of all time.

Morricone’s four main musical themes all evoke nostalgia in a slightly different way. Perhaps its most glorious moment [titled ‘From American Sex Appeal To The First Fellini’] is when the usually contemplative ‘cinema’ theme is taken through several different arrangements, some of them jazzy, in just four minutes. Cinema Paradiso in this version is only really weakened by evidence of its drastic editing which I wondered about even when I first saw it about 30 years ago. For much of the first half, Tornatore precisely links almost every scene with the scene that follows it both visually and aurally, creating tremendous smoothness despite the changes in tone. But after that some moments seem a bit choppy, some transitions aren’t smooth, and at the end of one scene you can hear not only the sound of a vehicle horn being tooted, but also, for a second, a video game being played. This is because originally the film transitioned into a scene set in a place where somebody is playing a video game. I’m surprised that Tornatore hasn’t fixed this by now. But on the other hand the presence of some loose ends and even some extremely subtle hints of what might or might not have been are still very pleasing. After all, life is full of unsolved mysteries. Cinema Paradiso remains highly meaningful to probably just about anyone who has nostalgia for youth and the past, memories of places and times that will not come back but which have made us, for better or worse, who we are today. And it’s total cinematic paradise to many of us film lovers, reminding us that the movies are indeed the best thing in the world and the cinema is the best place to be.

Rating:

SOME NOTES ON THE DIRECTOR’S CUT AKA IS ALFREDO THE MOST EVIL VILLAIN IN CINEMA HISTORY?

MAJOR SPOILERS!

Director’s cuts can often seem little more than cash-ins, but there are some which significantly alter a film, and this is most definitely one of them. Tornatore has stated that he loves both cuts of Cinema Paradiso equally. I adore both, but I believe the Director’s Cut to be slightly superior. It takes the form of three sections of a similar length; Salvatore as a child, Salvatore as a teenager, and Salvatore as middle-aged. In the audio commentary included on this release and several earlier ones, Tornatore says that the easiest way to cut his film down was to lop off a major portion of the narrative towards the end so that he could leave much else untouched, and he may have been right to do so seeing as the 124-minute [let’s call it the TV for Theatrical Version] became the version that the world fell in love with, though in doing so he basically removed one of the most important things in his story. This created a slightly more elusive work, and one where little really happens in its final section, for good or for bad. The DC provides a much more cathartic experience as well as leaving you with a less sunny feeling, something which undercuts the sentimentality some say is a flaw with the TV – though as I’ve often said I don’t see sentimentality as a problem if I feel it’s been earned. The DC leaves us thinking more, and asking ourselves what is most important in life, and whether significantly meddling in somebody else’s life to the point of causing them severe heartbreak is justifiable.

The first hour was left unaltered in the editing except for a few shots, making the childhood section the longest in the film. The second hour received some shifting around of scenes and the removal of both Salvatore and Boccia losing their virginity to the town prostitute, a character we meet briefly in the short version working in the cinema. These scenes are irrelevant though amusing [guess where Salvatore wants to have sex?]; I wonder if Tornatore removed them because he wanted a lower rating? And some material involving Salvatore and Elena was removed, including a very funny scene of Salvatore professing his undying love for Elena over the phone, only it’s his mum he’s talking to. Tornatore even partially ruined the romance of a kissing scene in the rain by cutting in shots of the middle-aged Salvatore and adding voice-over dialogue from another scene that was totally cut. While the romance isn’t the greatest part of the TV, it benefits from being fleshed out in the CD, coming across as a more important part of the film. And, importantly, it takes on a slightly darker hue with Salvatore’s love being more like an obsession. However, I must say that the truncation of some of the Toto/Alfredo dialogue scenes in the TV isn’t particularly harmful; at full length, they do slow the pace down even if we learn more about Alfredo. if I can’t do without any of them.

Salvatore in the army gets a longer montage; why this was shortened I don’t know. However, the most important of the material restored to the DC is Salvatore encountering Elena again when he returns to Giancaldo after so long. She first appears to him like an apparition in slow motion when he’s in a bar in a transcendently beautiful moment; but she hasn’t aged, so it can’t be her, can it? Morricone’s music is especially intelligent in these scenes; it’s the love theme, but without the actual melody line, a musical equivalent to Salvatore’s emotional state. The girl is actually Elena’s daughter, leading to a scene which is one of the most moving in the cinema, featuring absolutely incredible acting by Jacques Perrin and Brigitte Fossey, the latter’s appearance especially poignant if you know your French movies; her debut in 1952’s Forbidden Games is one of the greatest childhood performances ever. The two pour their hearts out to each other, Salvatore finds out something which changes his and our [a major reason why some lovers of the TV didn’t like the DC when they saw it] perception of Alfredo as well as learning that she married Boccia, and finally, after 35 years, the two get to make love, bringing their love story to an appropriate close. Cinema Paradiso is turned into a love story of considerable irony and heartbreaking proportions. In the TV, one cannot help to be greatly moved by the ghost-like elderly faces of people Salvatore once knew 35 years ago, Salvatore exploring the dilapidated cinema which was once the centre of his world, the dynamiting of said cinema [never has the destruction of something that isn’t actually a living thing been so tragic], and Alfredo’s gift of much of the censored kisses edited together in one rapturous reel. However, the DC adds even more tragic material yet stops short of becoming depressing.

So what heinous crime did Alfredo commit? When Elena showed up at the cinema to meet Salvatore, Alfredo talked her into leaving, thereby sabotaging their love. A horrible thing to do? I remember the IMDB forum [back in the good old days when the IMDB actually had forums] for Cinema Paradiso not just having fans debating on which cut was better [it was about 50/50], but whether Alfredo was right to break up Salvatore and Elena. One poster called Alfredo “the most evil villain in cinema history”, and I have to say that at the time I agreed. How dare he? Alfredo’s act of cruelty left Salvatore loveless for the rest of his life, despite the many nubile women he got to bed. But then think of it from Alfredo’s point of view. He seems to believe that great art and great love can’t exist side by side, while he also clearly noticed that Salvatore’s love was maybe not healthy. Notice how he tries to warn Salvatore off Elena right from the start. I believe that Alfredo once had dreams of being a filmmaker and projects those dreams onto Salvatore, and that he deliberately destroyed Salvatore’s romance so that it would be romanticised in his mind forever and never spoilt much like a movie, and may even fuel his art. So I guess that the answer is that what Alfredo did was wrong – but he honestly believed that what he was doing was right. Whatever, Cinema Paradiso‘s ‘stolen kisses’ gift now has more explicit meaning and added resonance. While Alfredo obviously hoped that Salvatore would never find out about Elena, his present still becomes no less than an apology for what he did – while also being a reminder of why he did it.

Rating:

SPECIAL EDITION CONTENTS:

New 4K restoration of the theatrical version from the original camera negative, supervised by Giuseppe Tornatore and 2K restoration of the Director’s Cut version

4K (2160p) UHD Blu-ray presentation in Dolby Vision (HDR10 compatible) of the 124 minute theatrical version

Thankfully Arrow didn’t send an actual UHD disc, as I wouldn’t have been able to play it. In any case, even on standard Blu-ray this is a magnificent restoration of a film that’s always had a somewhat problematic visual history on home media. It often alternates between harder and softer focus scenes, obviously a deliberate device, though this was only really clear on DVD where I was surprised by the softness on display, and also the heavy grain on some shots, most notably during the first segue from the present to the past. Blu-ray editions have understandably opted to slightly reduce the softness, perhaps more than they should have done, perhaps not, though it’s not anywhere near as drastic as it could have been. The colour in this latest version is the most vibrant it’s ever been; the film has always had quite a reduced palette for the most part, but here the occasional bright hues really stick out, while the dark cinema scenes show even more detail. And thankfully the battered state of most of the old movie scenes has been left intact. What was most interesting to me were the end credits which consist of clips from the film. Tornatore may have heavily cut it down but he left the end credits untouched, so a shot of actress Brigitte Fossey who was removed from this version remained along with her name being credited, followed by a shot of Salvatore that was also cut out. Why Tornatore left these in is anybody’s guess, but it seems to be a deliberate decision. For home viewing, the shot of Fossey was replaced and her credit removed, resulting in a jump in the credits even though the music playing over it stayed intact; the extra shot of Salvatore remained though. This new release restores this strange anomoly which also remained in the DC until now.

High Definition Blu-ray (1080p) presentation of the 174 minute Director’s Cut

Arrow only sent me the disc containing the TV, but I’d imagine that the DC is the same 2k restoration as in Arrow’s previous release of Cinema Paradiso which I own. There are a few instances of mild grain cluster, most notably in a couple of darker moments, but overall it bares up pretty well compared to the TV’s shinier 4k edition. Of course one can ask the question why the DC didn’t get a 4k polish too – though I think it will happen eventually.

Uncompressed original stereo 2.0 Audio and 5.1 surround sound options

Optional English subtitles

Audio commentary with director Giuseppe Tornatore and Italian cinema expert critic Millicent Marcus

This and the other special features were on the previous Arrow Blu-ray and indeed the DVD set which also contained a CD of the extended version of the soundtrack. The commentary, which is on the TV, is a little odd. Millicent Marcus feels it necessary to spend a lot of time informing us exactly what’s happening on screen, though she does add some good observations along the way and clearly loves the film. She explains how one scene is there to remind us of how the Italian Neo-Realism movement failed, how Federico Fellini was a big influence, and points out recurring issues such as class. Her introduction to the DC is most interesting – she and her class were in Italy and they rented out the film to watch, thinking it wouldn’t be any different from the version they were familiar with but instead being really surprised when all this new stuff started taking place before their very eyes. Parts of an interview with Tornatore are also heard, the man answering questions about things like the casting [Philippe Noiret liked the script so much he walked away from another film he was set to do] and the setting, though together his portions probably only comprise about ten minutes. A very worthwhile track in the end, even if it may not initially seem that way.

A Dream of Sicily – A 52-minute documentary profile of Giuseppe Tornatore featuring interviews with the director and extracts from his early home movies as well as interviews with director Francesco Rosi and painter Peppino Ducato, set to music by the legendary Ennio Morricone

This was originally on the Korean DVD release of Tornatore’s Malena from Spectrum. It’s a very ‘free-form’ piece which continually intercuts footage of Tornatore, his early movies where he basically went around with a camera and shot whatever he fancied, his theatrical releases up to The Legend Of 1900, and new footage of everyday Sicily, mostly Bagheria which is Tornatore’s home town, some of it consisting of a painter spouting poetry. There’s no real structure and the emphasis on Sicily and its people may distract some viewers craving for more stuff about his movies, but then Tornatore tells us that the latter clearly informs his work, much of it involving “searching in the Sicily of the past for the Sicily of the present”, and reflecting on how Sicily is most loved by Sicilians when they’re not actually there. He’s analytical about his work without seeming pretentious. The Morricone music is mostly, though not entirely, from Tornatore films, in what is an unusual but in the end a very rewarding piece.

A Bear and a Mouse in Paradise – A 27-minute documentary on the making of Cinema Paradiso and the characters of Toto and Alfredo, featuring interviews the actors who play them, Philippe Noiret and Salvatore Cascio as well as Tornatore

Of course a documentary on the making of this film ought to be much longer, but a lot is packed in to this one, and it’s great to see an older Salvatore Cascio. We hear how Cascio would invent things to do unlike most child performers and hated Noiret smoking [to the point where Cascio still hates smoking], how one part of the film the producers didn’t like was actually shot on the sly, and how at the a film festival Italian films had such a bad reputation at the time that Cinema Paradiso was thrown out until influence from a certain person got it restored. Full of stories and warmth even though it seems that filming was hard to the point where certain things feel like they’re being skimmed over, this is a must watch.

The Kissing Sequence – Giuseppe Tornatore discusses the origins of the kissing scenes with clips identifying each scene [7 mins]

We learn how Tornatore wanted Fellini to play the projectionist in the final scene, and Fellini’s very rightful response. I’m not sure that even Tornatore knows why this final scene evokes such an emotional response, but then I’ve struggled several times during this review to put my love of this film into words. Sometimes words just don’t do it.

Original Director’s Cut Theatrical Trailer and 25th Anniversary Re-Release Trailer

What else but Highly Recommended!

Beautiful, in-depth review, Doc, for what is one of the most magnificent films I’ve ever seen. I’ve only seen this and Deception but I’m a lover of Tornatore’s style of filmmaking. It’s absolutely captivating.