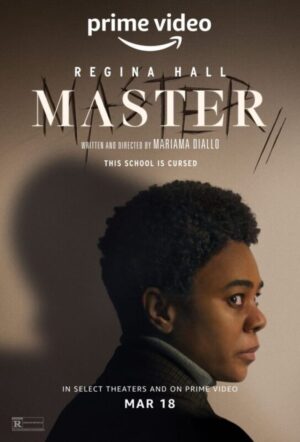

Master (2022)

Directed by: Mariama Diallo

Written by: Mariama Diallo

Starring: Regina Hall, Zoe Renee

MASTER

Directed by Mariama Diallo

As a genre, horror has a knack for giving voice to outsider perspectives: be it films about race, class, or sexual orientation, it celebrates stories about marginalised people. The latest from Amazon Prime, and the feature debut from Mariama Diallo, Master, is no exception. In it, we follow two black women struggling in a prestigious university, where students and staff alike have attitudes as old as the red-brick buildings they populate. First, there’s Gail (Hall), a recently tenured house master who has worked her way up to the upper echelons of her profession. Then there’s Jasmine (Renee), a new student staying in a room known, worryingly, as “the room”: a place which may or not be subject to a centuries-old curse involving alleged witchcraft, visions and eventually suicide. Peers repeatedly undermine both – they may be decades apart in age, but their experiences aren’t so dissimilar. What’s more unusual is that, along with their person problems, both seem haunted by an evil presence: whispers of a bygone era.

The campus atmosphere is wonderfully authentic. Whereas college campuses and dorms often act as a generic backdrop, the fictitious Ancaster feels like a living, breathing environment with its own legacy and traditions. Its hallowed halls and old brick buildings evoke a long lineage of academics and students walking the corridors: it’s the perfect place for a layered mystery spanning centuries. Even at the start, where Jasmine gets warned about ‘the room’, it feels like it could be a credible local legend. Likewise, while the dusty library books and papers could make for a pretty thin plot device, the movie’s so immersive that it didn’t bother me too much. We can see why our leads are mutually attracted to the place and feel shunned by it. This helps as, frustratingly, neither Jasmine or Gail is fleshed out. Jasmine, in particular, is a blank slate – mostly responding to events like a deer in the headlights (although I liked the nuances with which both understood their identity). Still, both actors add a lot to the film, bringing strength to what could easily be played as passive roles.

It’s disheartening to watch each try their best to navigate and fit in with an institution where they’ll never be seen as equals. Interestingly, the sorts of racism we see tend not to show up in horror films – or cinema more broadly. Some of it is subtle microaggressions – others are patronising, benevolent discrimination. Although it does escalate as it goes on, there’s not a lot of overt hateful racism on display for much of the running time. Nor do we have a satire of overcompensating liberals ala Get Out – which Master will inevitably be compared to. Instead, much of it is ignorant and unthinking. It’s a banality: incessant flickers of blatant prejudice and othering combine to wear our leads down. Think campus security guards who don’t seem to check everyone, crude nicknames such as ‘Obama’ or ‘Lizzo’. Or an uncomfortable party sequence where white frat boys gleefully sing along with the N-word. Then there’s the implicit and consistent bigotry of academics. As Gail says, it can be hard to define or pinpoint – and that’s what gives the film a fresh power. It’s always there, lingering in the background – like a ghost.

This brings me to the scary bits. While Master excels as a college drama, I was less convinced by the horror elements, which are few and far between. The individual scenes look good, though they mainly consist of dream sequences and slightly cheap tactics like oodles of maggots in all the wrong places. As such, it lacks a sense of sustained dread. In its best moments, the film is disorienting. But more often than not, it’s vague and repetitive to the point of frustration. Jasmine’s breakdown still worked for me – but that’s more because I was invested in the performance rather than the strength of the storytelling. I can see what Diallo is going for with the metaphor: a multigenerational treatise on why we cannot understand racism today without looking to the past. Yet the symbolic threat is better characterised than the literal one and, come the end, I didn’t think the witch herself had enough of presence. It’s a saturated market for supernatural horrors, and as with the limited set pieces, she wasn’t memorable enough.

The main thing I suspect this film will be remembered for is its ending. Without going into specifics, it goes in a very different and much darker direction than I thought it would. A frustrating statement where many viewers will want resolution. This is no bad thing: it’s a provocative final act, and the events themselves are effective. Yet it’s a change in focus and style that I think many, including myself, will be let down by – something which may even be the point. You go in there expecting a traditional resolution for reassurance and, without saying why, that’s not what happens. The trouble is Diallo arguably forfeits the plot in pursuit of the film’s meta-discussion about race. Meaning where we should be getting the payoff we’ve been hoping for across the last hour and a half, there’s a short burst before it fizzles out. Not that this sort of story can really have a definite ending. What change we see is incremental, and events echo on as history repeats itself again and again.

Rating:

Be the first to comment