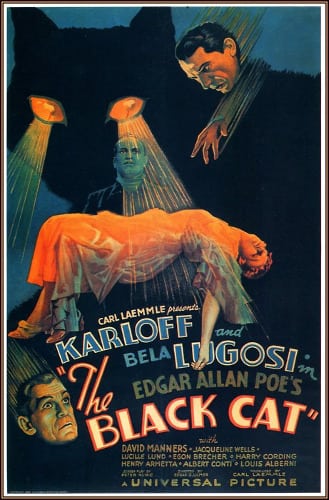

The Black Cat, Werewolf of London (1934, 1935)

Directed by: Edgar G. Ulmer, Stuart Walker

Written by: Edgar Allan Poe, John Colton, Robert Harris

Starring: Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, David Manners, Henry Hull, Valerie Hobson, Warner Oland

Two young honeymooners, Peter and Joan Alison, are travelling to Hungary when they learn that, due to a mix up in the reservations, they must share a train compartment with Dr. Vitus Werdegast, a psychiatrist who claims that he is travelling to see an old friend, Hjalmar Poelzig. Werdegast seems interested in Joan and explains that many years ago he lost his wife during the First Word War and has spent fifteen years in a prison camp. The three share a car but it crashes during a powerful storm and they end up at Poelzig’s strange abode, which is built on the ruins of Fort Marmarus, the site of a bloody battle where, it is learnt, Poelzig not only betrayed the fort to the Russians but stole Werdegest’s wife. Then Peolzig says to Werdegest that they should play a game of chess – for the lives of Joan and Peter….

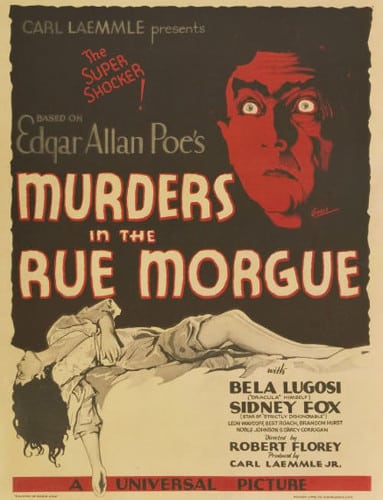

The first of eight films in which Boris Karloff would star with Bela Lugosi, The Black Cat is certifiably bonkers, a mad, glorious mixture of twisted relationships, sadistic revenge, sexual repression, Satanism, necrophilia and general insanity. In many ways it’s like Murders In The Rue Morgue, and even a cursory viewing makes it obvious that it was severely cut down, but it’s a more consistent movie than Universal’s previous Edgar Allan Poe adaptation; strikingly artistic, constantly on the verge of parody but continually aware of this, and though, as with many of these early Universal horror films [the 40s movies would generally be much faster paced], its initial slow pace may make it hard for some modern viewers to get into the film, it is absolutely fascinating to study from scene to scene, and not least because it suggests so much perversity and touches on so much dark subject matter while not actually showing much on screen at all. I certainly like my sex and violence and gore, but watching these old movies really brings home to me how clever these old films were in hinting and suggesting things that they could not show, and it almost seems like a lost art.

It was directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, one of the most interesting of the many European talents who emigrated to American during the 1930, and one whose work was often neglected at the time of release but which has attained a strong cult following. The Hungarian born filmmaker began his career with a film about venereal disease called Damaged Lives, which was partly educational and partly exploitative, and for some reason he was chosen by Universal to helm their second Poe’s adaptation, though the result only used the title and a black cat which appears every now and again. Perhaps because it was sure to be a hit, Ulmer, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Peter Ruric, was initially given free rein in making the film, and based Boris Karloff’s character and some of the story on Satanist Alistair Crowley. However, Ulmer clearly had little knowledge of the censors of the time, because his initial 90 minute cut was eviscerated by Universal as there was no way it would have got through. I shall go into the cuts in detail later on, because they really show evidence of an extremely vicious and perverse movie, but some might say it still is those two things, at least for the 30s. It’s possible that some material was reshot, but despite all this hassle the film became another huge hit for Universal, perhaps not surprising as it brought together the two greatest horror stars of the time. It has remained in circulation, and after Detour it remains Ulmer’s best known and most seen film, though soon after its release it was discovered he had been having an affair with the wife of a producer who was the nephew of Universal studio head Carl Laemmle, and was subsequently exiled from the major Hollywood studios and spent the rest of his career making ‘B’ movies at Poverty Row studios like Monogram.

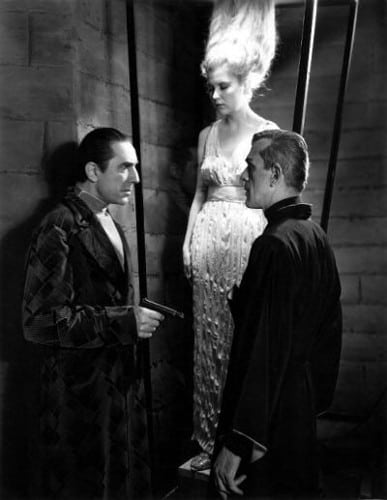

At first The Black Cat seems awfully similar to The Old Dark House, with some people forced by a storm to take refuge in a strange house populated by odd folk, though of course Werdegest intended to go to Peolzig’s house all along, and there are odd touches right from the very beginning. Werdegest strokes Joan’s hair while she is asleep, and though it’s soon proven that he’s on the side of ‘good’, this begins a certain ambiguity about his character, who does of course end up being a complete sadist even if he does save the day. Threaded throughout the film is also the delicious irony of Joan thinking that he is actually a villain. The film is slow and talky for quite a while, but it still gets more and more insane pretty quickly. Poelzig is first seen through curtains in silhouette, slowly rising from his head like a corpse, and immediately shows his lust for Joan by gripping the arm of a nude statue of a woman, while Werdegest demonstrates a fear of cats by throwing a ruler at one, killing it. Then, in a rather dreamlike and wonderfully Gothic sequence which possibly influenced Mario Bava, Poelzig wonders around a darkened room in which he has stored and preserved the bodies of female victims in glass containers. We are left in little doubt as to what he does with these bodies, and it is soon revealed he also has the body of Werdegest’s wife in similar condition, saying :“is she not beautiful? I wanted to have her beauty always”. Poelzig seems to have a ‘living’ girlfriend who never leaves his bed and is totally in his power.

A certain revelation possibly adds paedophilia to the list as the leisurely paced but hypnotic film speeds up towards its climax, which takes in among other things a black mass and flaying [honestly], and at times ceases to make much sense, maybe due to the cuts. The climactic fighting obviously has shots missing, though the disjointed feel seems almost appropriate to the astonishing sets. Poelzig’s house is one of the craziest horror film houses ever, one half futuristic and almost James Bond villain-like, and one half strikingly Gothic, with John Mescall’s photography revealing strange geometric patterns. Art director Charles D.Hall was clearly influenced by German Expressionist films like Nosferatu and Metropolis, which Ulmer claimed to have worked on, but takes it to a whole new level of weirdness for this film. Sometimes the design is totally unrealistic, with beams in places they realistically could not be, but it really doesn’t matter. Also fascinating is the script, which rather than being a traditional story of good versus evil, brings in many other themes such as post-war disillusionment whilst somehow still remaining true to its pulp elements.

Now the original cut of The Black Cat supposedly included such delights as Werdegest raping Joan [you’d expect it to be Poelzig doing this sort of thing], Joan actually being a black cat [the script as it stands contains odd allusions to supernatural powers of cats], Poelzig crawling across the floor with his skin hanging off, and more direct references to devil worship, plus all of John Carradine’s footage as an explosives expert aiding Werdegest. This really hints at a horrific film and as with the similarly mutilated Freaks, it’s hard to see how anyone would have thought that the censors of the time would have approved it. Some have actually said that this footage was never actually filmed and was just in the original script, but both Carradine and co-star David Manners have mentioned some of the cutting. One thing is sure though – we will probably never see the footage because snipped scenes were usually destroyed, but if you watch the film closely you can see vague hints of all I have described above plus other horrors. What is amazing is that the film flows as well as it does, and only really shows evidence of the cutting from about two thirds of the way through.

Karloff is, yet again, on top form here. His performance almost comes across as a nastier variant on his role in The Mummy, certainly walking in a similar way, and really sends the chills down your spine every time he appears. Again he proves what an outstanding actor he was, refusing to ham it up, and able to suggest things like sexual perversion with just a glance. Lugosi isn’t really up to his level, but still fares well, especially in some lengthy speeches where he goes into his sad past. They are wonderful together and even make a simple scene like playing chess interesting. With these two, Julie Bishop and David Manners [his third nominal ‘hero’ role for Universal] hardly have the chance to make much of an impression. One annoying thing about The Black Cat is its score by Heinz Roemheld. In contrast to previous Universal horrors, this one has almost continuous music, something that would become almost the norm in successive films, but here the composer constantly mingles in classical pieces. He sometimes changes the odd note, but it’s extremely annoying suddenly hearing a bit of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet, or Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 just as you are getting into a scene. This film would have probably been better off with no score at all, but even in its released form, The Black Cat is a totally unique film, extremely daring and perfectly straddling the divide between seriousness and silliness [there is little outright comedy except a very random bit where two policemen argue as to which of their home towns is better!], and Karloff and Lugosi are serious, but you still sense everyone is having a bit of a lark. This was actually the first time I had seen this particular film, and I found it absolutely fascinating.

Wilfred Glendon is a wealthy and world renowned botanist who journeys to Tibet to 1935 in search of the elusive Mariphasa plant. He succeeds in obtaining a specimen, but is attacked and bitten by a werewolf. Back home in London, he is visited by Dr. Yogami, another botanist, who says he met him in Tibet and warns him that he will become a werewolf, adding that the Mariphasa is a temporary antidote. Meanwhile Wilfred’s neglected wife is becoming more and more friendly with her childhood sweetheart Paul Ames. Wilfred manages to quell his lycanthropy the first time with the plant, but after Yogami steals the remaining specimens, the next night he becomes a werewolf and goes out to kill….

I’m going to start this review by saying to any expert on old horror movies who reads it; yes I know Bride Of Frankenstein was the next Universal chiller, but I am going to review it on its own, basically because it’s one of my favourite movies of all time and I think it deserves it. So, moving on one film, we have Werewolf Of London. Usually considered to be the first proper full length werewolf movie [there had been the 1913 short The Werewolf, also from Universal], Werewolf Of London has been considerably overshadowed by the later The Wolf Man, and understandably so, but though not really a classic, it’s still a highly enjoyable production. For the most part it moves well and interestingly treats its subject matter in a somewhat more scientific manner than would usually be the case, but disappointingly lacks much of the expected atmosphere. It also contains a plethora of comic relief which just seems to be there to pad out the story and appears to be in the wrong film, though most of it is still pretty funny. It has the feeling of not quite knowing what to do with its subject, but it is certainly fun and has some memorable bits and pieces dotted throughout, even if overall it’s very uneven.

Though Bride Of Frankenstein has been popular, it had had censorship trouble and The Black Cat, despite being similarly popular, had caused a great deal of problem in that area, so for Werewolf Of London, the studio chose journeyman director Stuart Walker to helm the project. The script by Harvey Gates and Robert Harris wasn’t officially based on any source material, though the title was possibly influenced by Guy Endore’s very different werewolf novel The Werewolf Of Paris, and it seems that Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, or rather the great 1932 film version of it, was an influence too. Bela Lugosi was considered for the title role, but it was thought that he wouldn’t have been sympathetic enough and so Henry Hull, a character actor with dozens of diverse credits to his name but few lead roles, was chosen. He refused to wear makeup artist Jack Pierce’s original makeup because he found it too time consuming to put on and take off, so Pierce created a much lighter look for the werewolf. He did though save his original design and that was the one used later in The Wolf Man. The censors removed a shot of the the werewolf slashing the face of Dr Yogami, though it seems that scenes featuring a ‘specialist’ whom Wilfred consults and a boy being attacked by Yogami’s plant were deleted because they were considered unnecessary. For reasons unclear, Werewolf Of London flopped at the box office. Perhaps audiences were getting tired of the horror films that had been flooding cinemas the previous few years, perhaps it was considered too much like Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, orperhaps Hull was not really a marquee name, who knows?

The opening Tibet sequence gets the movie off to a fine start, even though the studio set looks very different from the long shots of explorers actually in Tibet. We see a slightly creepy shot of the werewolf’s face rising up from behind a rock, then the attack is shown entirely in long shot, probably to avoid showing much of the violence, though it’s quite effective this way. Then the film slows for a bit and turns lighter, with much time given to chat at garden parties and Lisa’s friendship with Paul her old flame. Still, Wilfred’s gradual turning into a werewolf is nicely built up. First of all only his hands briefly change, then the following night we have a really great scene where Wilfred’s cat snarls at him, obviously sensing what is to happen the way animals can often do, and Wilfred walks behind some pillars, looking more and more transformed each time he steps out from the proceeding pillar. This is superbly done and was nicely paid homage to in the recent The Wolfman remake. After this it’s much werewolf action, with very effective use of the monster’s shadow just before the first killing and a rather scary little bit when the next victim pulls out her mirror to do her face and sees the werewolf’s face reflected. There’s not enough mounting tension though when it becomes apparent that Wilfred is going to try and kill Lisa though, and the climax is over rather quickly, with one simple bullet [which isn’t even silver] killing the werewolf, though it’s a bit unsettling when he talks just before he dies.

The minimal werewolf makeup is reasonable but it’s sometimes hard to think of him as a werewolf; he even dons hat, coat and scary before he goes out. He’s also amongst the wimpiest of screen lycanthropes, fine attacking women but when he goes for a male is easily fought off. What does work though, is his bloodcurdling howl, which was a combination of Hull’s own voice and that of a wolf. There isn’t enough atmosphere in this movie, but when you here that howl, which might just be the best werewolf howl ever, a surprisingly strong sense of fear is evoked. it’s not really unsurprising that the horror and violence was toned down for this film, with all the werewolf killings off screen, though it’s interesting that this werewolf seems to go mainly for streetwalkers or floozies, perhaps in a warped way relating them to his wife. Then again, in the way it presents some of its characters, the film is quite interesting. We are presumably intended to like Lisa and Paul’s growing romance, but don’t we feel a bit sorry for Wilfred and almost wish he will rip apart the guy messing around with his wife? The film’s final image of Paul’s plane flying, implying that Lisa, who no longer has the burden of a neglective husband, is off to find sexual bliss with Paul, leaves a bad taste in the mouth though. It’s said of Werewolf Of London that its lead character is not very likeable, but I disagree, though it would helped if the early scene where he saves a boy from being swallowed by a large plant had not been cut out.

The plot isn’t as worked out as it perhaps should be, especially concerning Dr Yogami. When he says to Glendon when he first meets him in London: “We met once in Tibet, in the dark “, it’s obvious that he was the werewolf that attacked him in Tibet. It would have worked better if his identity was kept more of a mystery, and also if he had done more than just turned up every now and again. I don’t think the writers knew what to do with his character. Now I’ve already mentioned the comic relief and how it’s out of place, but I do laugh at Ettie Combes and Mrs Forsythe, the society dames who talk absolute nonsense, from calling Yogami Yokohama to one saying that she once sat on a salad and wasn’t told about it. Even funnier are Mrs Whack and Mrs Moncaster, brilliantly played by Ethel Griffies and Zeffie Tilbury, the two elderly gin-drinking ladies who like to knock each other out. They are straight out of a James Whale film, but just don’t really belong in this one. I also like the disbelieving police chief who says: “This is Scotland Yard dear boy, not Grimm’s fairytales”.

Stuart Walker doesn’t show much affinity for horror, but does throw in the odd interesting quirk, such as a section of plot represented by lots of short telephone calls. Henry Hull’s performance has been much criticised, but I rather like it. This is a stuffy, dull man who in a way finds some youth and vigour when he becomes a werewolf, and Hull effectively transmits this, though some more background about his character would have helped the film, and also as to how he and wife got together. Valerie Hobson, who is twenty seven years younger than Hull, had just starred in Bride Of Frankenstein and is likeable that she almost makes a rather unsympathetic character sympathetic, though I’m never really convinced by her acting. Warner Oland makes Yogami a sinister variation of Charlie Chan who he had already played several times and it works very well. The music for Werewolf Of London is credited to a Karl Hajos, and he was probably responsible for the simple but effective three note motif for Wilfred and some strong scoring during the transformations, but much of the music appears to come from The Black Cat, or should I say various classical composers! Needless to say, it jars. Overall Werewolf Of London is certainly worth seeing, it’s entertaining and has some interesting aspects, but is only sporadically as effective as it should be and it was Universal’s next try at a werewolf film six years later that would do the subject more justice.

Be the first to comment