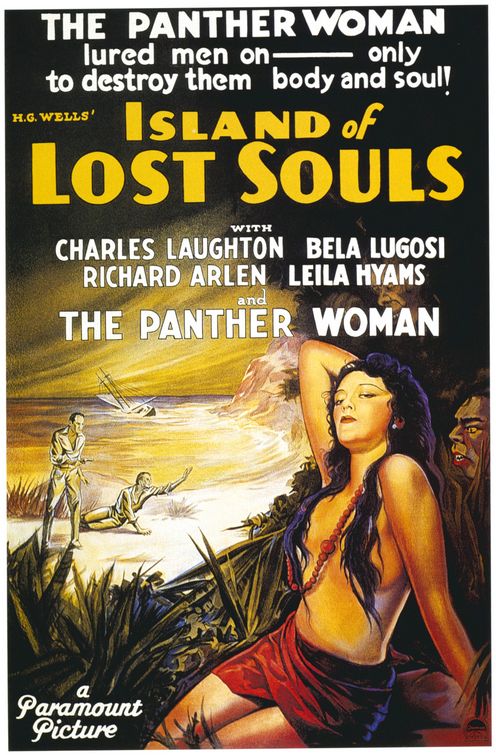

Island Of Lost Souls (1933)

Directed by: Erle C.Kenton

Written by: Philip Wylie, Waldemer Young

Starring: Charles Laughton, Kathleen Burke, Leila Hyams, Richard Arlen

AVAILABLE ON BLU RAY: From May 28th, Eureka Entertainment ‘Masters Of Cinema’

RUNNING TIME:71 mins

REVIEWED BY:Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

To the consternation of his fiancée Ruth Thomas, Edward Parker is lost at sea, his ship destroyed by a storm, but he gets picked up by a freighter that is delivering supplies to an isolated South Seas island owned by the mysterious and private Dr. Moreau. After a fight caused by Captain Donahue’s striking of a deformed servant, Parker is thrown overboard into Moreau’s boat, so that he ends up an unwitting guest on the island, which appears to be populated by strange, beast-like men ruled over by Moreau. After witnessing one of them being given surgery without an anaesthetic, Moreau explains that for many years he has been experimenting with accelerating evolution, first plants, then animals whom he tries to turn into humans. He was banished from London because of this, but is getting closer and closer to complete success. However, the population of animal-men is growing, and why does Moreau want the beautiful Lota, whom he made from a panther, to get friendly with Parker…..

Despite the fact that this fully restored version from Eureka Entertainment now has a ‘PG ‘certificate from the BBFC, something I don’t really agree with, Island Of Lost Souls is an amazingly nasty, disturbing but rather thought-provoking horror from the 1930s, and while it may not be as transgressively bold as the previous year’s much better known and similarly controversial Freaks, I would say it’s more compelling and transmits its themes better, partly because it’s a much more cinematic piece. It was the first of three film versions of H.G.Wells’ 1896 book The Island Of Dr Moreau, which, more than probably any of his stories, combined an exciting and imaginative tale with much social and political comment, and was in particular a savage attack on animal experimentation. The 1976 movie version is a good yarn, and the troubled 1996 version, which could possibly have been a masterpiece if original director Richard Stanely hadn’t been thrown off the project, remains good fun. Many films, though mostly of a low budget kind, have borrowed from the concept such as Twilight People and Superbeast. This 1933 film, though, remains by far the best of the adaptations, a powerful, harrowing experience that really gets under your skin. It may not be regarded as highly as, for example, Frankenstein is, but it’s more frightening and horrifying, and though not as famous as it should be, has inspired many pop songs, from Devo, Oingo Boingo and others.

Island Of Lost Souls was made by Paramount [coming off the success of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde] and had a comparatively large budget, larger anyway than your average Universal horror movie of the time, though it was still filmed entirely on the Paramount Ranch and, for a few shots of Moreau’s island, Catalina. The original script was even stronger than the one used and included such delights as Moreau beating Lota to death and a monster with no face, with Moreau out to cut off Parker’s face and put it on the creature! One of the many un-credited extras nearly drowned and another was mauled by a tiger, but the real difficulties occurred after production. Though passed uncut, most American states cut bits out they found offensive, with the sight of Moreau vivisecting someone being the bit that was most removed. Eleven countries banned the movie, including the UK, where in 1951 and 1958 it was turned down again until finally getting a limited (still cut) release in 1958, maybe because of the Hammer films that were starting to come out. As for Wells, he publically expressed his hate for the film, which added two female characters and omitted the final section of the story where the animal people’s society starts to fragment a la Animal Farm. He thought that the horrific aspects overshadowed the philosophical, political and ethical themes that he felt were very important. Well, he may have been right, but in my view they are all still there, in spades, and strengthen, rather than diminish, the movie.

The film wastes little time, maybe just ten minutes, getting to the island, and even before that a powerful feel of unease quickly makes itself present in the scene where the ‘dog man’ on the ship appears. He’s a pathetic creature, and is immediately engineered to create our sympathy when the Captain abuses him, while watching dogs show their dislike. He’s also very creepy though; he hobbles along, his face is weird and he appears to have the ear of some kind of animal sown on. We are shown some other crew members, similarly odd, in an almost casual way, then, once on the island, beast-men are constantly lurking in the shadows, from behind trees, looking in windows, and yet we are rarely allowed to see them in detail, making the uneasy atmosphere all the more stronger. The makeup by Wally Westmore is surprisingly minimalist, making these creatures far more human than animal, and for me this makes them very creepy indeed, along with their wierd noises, which were foreign dialects and animal sounds played together at varying speeds. The film becomes an early kind of torture movie when it becomes apparent what ‘The House Of Pain’ is. While at dinner in Moreau’s house, we hear a cry of pain, and the ‘dog man’ shivers, making it clear that he has been in ‘The House Of Pain’, and soon after is a really shocking scene for the time. Parker, having been woken up by the horrendous cries of pain, sees Moreau with a monstrous ‘man’ on a bed, obviously vivisecting him, the victim in total agony. We may not see the gore,but it gives a really grim edge to the rest of the film, actually helped by us not knowing exactly the details of his ‘work’, though early on he says how he began using “plastic surgery, blood transfusions, gland extracts, and ray baths”.

Another plot element has Moreau obviously want Lota to mate with Parker, and there’s a striking bit where she ‘comes onto him’ in the most blatant way, but the passion is short lived, because Lota’s claws start to come back. So what does Moreau do? He tries to arrange it so that one of his beast men can go and rape Ruth! For much of the time though, these creatures are quite sympathetic, and though her screen time is not that much, Lota really makes an impression as one of horror cinema’s most tragic heroines. However, in Freaks-like fashion, the creatures’ horrific aspects are used to their full in the stunningly vivid climax, where director Erle C. Kenton has their often revolting faces loom into the camera, and their gathering of surgical equipment is all you need to know for what follows. Sometimes the imagination is far more powerful than anything a filmmaker can show you. Another disturbing scene has characters enter a room which has on display what appear to be Moreau’s experiments with sea life, and the camera briefly pans around the room, revealing aquatic creatures that don’t quite look right, though you can’t quite put your finger on why.

Amidst all this, Wells’ themes are certainly present, along with more other pertinent ones such as miscegenation and even colonialism – isn’t Moreau like a racist ruler of a new found country, trying to turn the natives into nice white men? These days, things such as factory farming and genetic engineering make the film still very timely; in fact, the recent Splice made me think that a really good modern day version of this tale could be made, though I think it would lose much of the element of pain that dominates this version. As with many films of this era, some of the dialogue scenes don’t come off too well when seen through modern eyes, and you may laugh when Moreau says a variant of that famous line, “they” – the natives – “are restless tonight”, though I wonder if that was intended to amuse, since the film is deadly serious otherwise. It’s undeniably stagy in parts, but its claustrophobic atmosphere is stifling in the most intense way, like a pressure cooker about to boil over, even in the outdoor scenes. Director Kenton, best known for three weak but fun instalments of the Universal horror cycle from the 40s, was never an especially interesting director, and the look of this movie seems more due to cinematographer Karl Struss, with superb use of tight framing and lots of shots where the action in the middle of the picture is surrounded by virtual darkness, as if the characters are in a nightmare from which there is no escape.

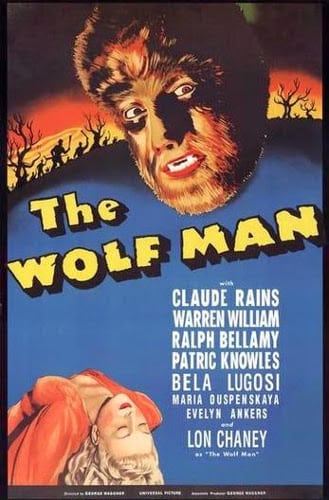

The acting, I must say, is a decidedly mixed bag, with Richard Arlen a very bland hero, though Kathleen Burke’s bizarre looks and movements make Lota all the more intriguing, and Bela Lugosi makes a strong impression in a small role as the leader of the animal men. Supposedly he took the role to show he could handle make up, having previously turned down Frankenstein for that reason. In any case, the film belongs to Charles Laughton as Moreau, one of cinema’s greatest mad scientists. Of course he believes that what he is doing will benefit science, but clearly is a sadist and even some kind of sexual deviant, going by some of the strange looks he gives. He often gazes off screen, and most scarily, he almost constantly has an evil smile, as if he finds it all a little amusing. He rarely explodes, but when, after Lota’s claws have returned, he cries, “this time I’ll burn out the animal in her”, he does it with terrifying glee, in no way concealing the fact that he will enjoy, maybe even ‘get off’ on the horrendous surgery he is about to perform. Even more disturbingly, he laughs when he being vivisected himself. Every time I view this film, I am struck by its power, its ferocity and its grimness, going full tilt at its subject matter in a way I’m not sure many filmmakers, at least of the commercial kind, would do today.

This is the first-ever Blu-ray or uncut DVD release of this Universal horror classic in the UK, finally released in time for its 80th anniversary. The Masters of Cinema Series is proud to present Island of Lost Souls on Blu-ray and DVD, available in the UK in a standard Dual Format Edition & Limited Edition Dual Format Steelbook from 28th May 2012.

SPECIAL FEATURES:

New high-definition restoration of the uncut theatrical version, officially licensed from Universal Pictures

Newly created SDH subtitles on the feature for the deaf and hard of hearing

Uncompressed original monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray

An exclusive video piece in which horror critic and historian Jonathan Rigby discusses the film and its source novel

Original theatrical trailer

A lavish booklet featuring rare production imagery, and more!

1 Trackback / Pingback