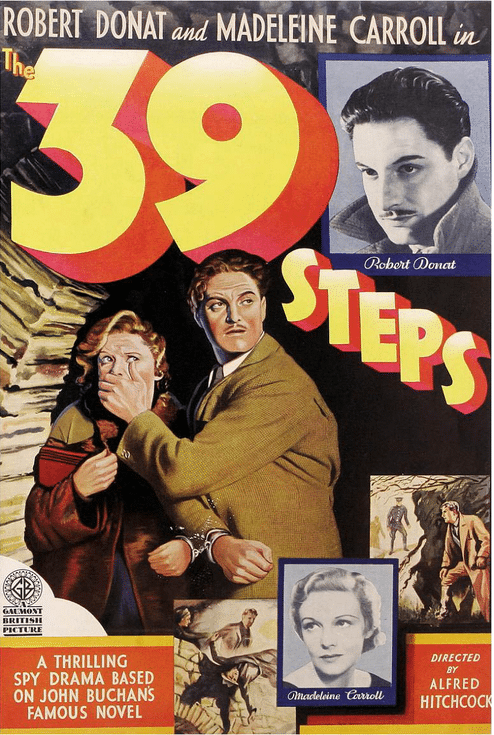

The 39 Steps (1935)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Alma Reville, Charles Bennett, Ian Hay, John Buchan

Starring: Godfrey Tearle, Lucie Mannheim, Madeleine Carroll, Robert Donat

UK

AVAILABLE ON DVD

RUNNING TIME: 82 min

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: Tossing a white cigarette box while the bus pulls up for Robert Donat and Lucie Mannheim to leave the theatre

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Richard Hannay is in a London music hall watching a demonstration of the superlative powers of recall of “Mr. Memory”, a man with a photographic memory, when shots are fired. In the ensuing panic, he finds himself holding a seemingly-frightened Annabella Smith who talks him into taking her back to his apartment. She says she is a spy, and has uncovered a plot to steal vital British military secrets. Later that night, she bursts into Hannay’s bedroom, fatally stabbed in the back, and warns him to escape. He finds a map of Scotland clutched in her hand, with a town circled. He sneaks out of the watched apartment disguised as a milkman and boards a train to Scotland, where he sees the police searching the train and learns from a newspaper that he is the target of a nationwide manhunt for Smith’s murderer….

A terrifically inventive and charming romantic thriller which after the first 15 minutes or so moves at a fantastically fast pace, this is usually held up as Hitchcock’s best British film. I would actually say The Lady Vanishes holds that title. The 39 Steps has the slight flaw of moving so fast that bits of it don’t quite sense, and feels so cut to the bone that some details could do with being explained more clearly, but you can say that about many modern action movies, and the 39 Steps is almost the 1930’s equivalent of one, a brisk yarn where the hero is constantly on the run and in danger wherever he goes. Like the earlier incarnations of 007, who also shares his ability to get every young woman he meets to fancy him, he has to rely on his wits as well as sheer toughness to get out of all the deadly situations he finds himself in. When I was first getting ‘into’ Hitchcock, The 39 Steps was the first of the British pictures I saw and wasn’t actually too impressed by what seemed a somewhat rough and ready film after the smoothness and complexity of many of the American films, but I was only a teenager and soon realised my mistake. Though he had previously made two very strong pictures in The Lodger and The Man Who Knew Too Much, The 39 Steps is Hitchcock’s first classic.

From The Man Who Knew Too Much onwards, Hitchcock would usually be given virtual carte blanche to film whatever he wanted. He and Charles Bennett went straight to work on adapting John Buchan’s novel The Thirty-nine Steps, choosing to stay in the world of their previous film. They threw out much of the book, altered many other things including the steps of the title not being actual steps leading to a spies hideaway but the name of an organisation of spies which is doing nefarious things, and added some female characters including the romantic interest. Even the music hall opening and closing were new. On the first day of shooting, Hitchcock had leads Robert Donat and Madeleine Carroll, a star imported from the US, handcuffed together for most of the day while he pretended to lose the key. They brought a load of sheep for one scene, but it didn’t occur to them that the animals would immediately get to work on the bracken and bushes that had been brought with them. Hitchcock chopped bits out of the script including a scene showing aircraft being built secretly, and after completion of the film even cut a final scene where hero and heroine realise they are actually married, because in Scotland if you declare you are married to witnesses, even if you are pretending, the marriage is legal. The film was a sensational success and even Buchan liked it, saying his book had been improved upon.

The character of Mr Memory, who opens and closes the story, was based on an act Hitchcock, who frequented music halls as a kid, once knew. Hitchcock perfectly recreates the boisterous and slightly seedy atmosphere, but there’s no wasting time here, because a shot is fired, panic ensures, and Hannay finds himself with a woman who asks if she can come home with in – something which he accepts. This is rather daring for the time, especially when in the next scene she says she is an actress but “not that sort” [a prostitute], but then this film is quite brave throughout, from Hannay telling a milkman he’s been visiting a married woman, to the two guys on the train who talk about and sell women’s underwear, to the unmarried Hannay and Pamela sharing a bed. And then there’s the emphasis on Pamela taking her stockings off. Of course the kinky elements of a man and a woman handcuffed together speak for themselves, but even their first meeting is unusual, Hannay being chased on at a train, bursting into her cabin and suddenly snogging her so he can’t be seen. She seems to enjoy it after a second or so, but still betrays him to the police a few seconds later.

The early scenes between Hannay and the mysterious Annabelle go on for quite a long time but her death, superimposed and lurching forward towards the bed of the waking Hannay until we see the knife in her back, is memorable, and then the Fugutive-like chase is on. Hannay is pursued on a train, through the streets of a Scottish town, and through the highlands. He jumps from the train onto a bridge, which is fine [and also looks pretty good technically], but he also smashes through the window of a police office when he has had one hand handcuffed. Sometimes Hannay is more of a comic book hero than a believable ‘everyman’ just caught up in bad situations, but some of the transitions employed to take the story past material that might slow it down are ingenious. At one point Hannay is actually shot, and is seen to fall to the ground, but in the next scene a man holds up a hymn book which had been inside Hannay’s jacket and had obviously been the thing that stopped the bullet, prompting someone to say, “those hymns are terribly hard to get through”. The manhunt is detailed by radio broadcasts over a shot of a bridge. There’s exactly the right amount of humour throughout; it’s never overdone, never takes away the danger element, and is often combined with it. At one point, Hannay finds himself being chased for the umpteenth time and runs into a room where he is mistaken for a politician booked to give a speech. What does he do? He pretends to be the politician, and after beginning rather awkwardly gives a rousing nationalist speech that has the audience cheering.

It all climaxes with an assassination in the Albert Hall [shades of The Man Who Knew Too Much] which is maybe a little weak compared with what has come before, but the ending has a nice line in irony: Mr Memory has to always tell the truth, so is compelled to say what the thirty nine steps are, but dies before he can go into much detail. There’s something about a design for a silent aircraft engine, and in truth the basic story is extremely flimsy. It was for this film that Angus MacPhail coined the term ‘MacGuffin’, something that everybody is after and propels the plot, but which is basically meaningless and doesn’t bear too much thinking about. You could say that in the end The 39 Steps is a little shallow, but it’s crafted with great ingenuity and certainly doesn’t lack for heart. The bickering between Hannay and Pamela, who initially hate each other, ends when Pamela is given a beautiful close-up with a lovely ‘look of love’ on her face, but the most touching bit in the film is when Hannay spends the night at the house of a crofter. Through almost silent-movie techniques, Hitchcock shows immediate attraction between the two, and the look on her face after he has kissed her goodbye is very moving. Hannay is so cool throughout the film; he really is someone men want to be and women want to be with [or at least someone men think women want to be with!]. There is though a scene where he orders himself a whisky and Pamela some milk which now seems very dated.

Hitchcock’s direction is probably perfected with this film. His style is less over-the-top than in many of the silent films [and some of that was because of the lack of sound] but still quite stylised for the time with lots of close-ups [Hannay is introduced by shots of his legs, indicating he is, at least for the moment, an ‘everyman’ in a crowd] and clever transitions. Donat is suitably dashing, though he doesn’t quite seem frightened enough, and Carroll is luminous. Godfrey Tearle is somewhat un-menacing as the chief villain, but that’s probably to emphasise the fact that outwardly he leads a normal and respectable life. Evil in normality was already becoming a favourite Hitchcock theme. Louis Levy’s score just consist of the occasional cue but it works well enough. The 39 Steps, which develops favourite themes Hitchcock had used less elaborately before like the man on the run and the heroine thinking the hero is a killer, may, in the end, not bear too much scrutiny in terms of its plot, but it’s glorious escapism that seems almost as lively now as it did in 1935. Its somewhat flippant attitude actually seems quite modern. Hitchcock would partially remake this film as Saboteur in 1942 and North By Northwest in 1959, while Donat’s novel would not only also be filmed in 1959, 1978 and, in a much more faithful version, for TV in 2008, but also be adapted for radio and stage.

Be the first to comment