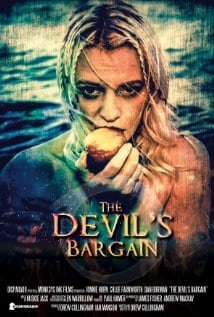

Unseen. Uncertified. Unmissable. Drew Cullingham (UMBRAGE: THE FIRST VAMPIRE, BLACK SMOKE RISING) has written and directed a savage, psychological portrait of love, lust and the end of the world, which is now available to watch for just £3.99.

Drew discusses the ideas behind and making of the film, THE DEVIL’S BARGAIN.

Tell us what inspired you to make THE DEVIL’S BARGAIN?

The ‘genesis’ for the story came from lengthy conversations between myself and the co-producer, Ian Manson. He had ideas floating about his head based on a story he’d read about two women facing the end of the world, and what they would do in such a situation.

This was about the time of the lead up to the anticlimactic 2012 apocalypse that never happened. I know, shocker! The initial discussions were wide ranging and incorporated the troubling fact that our analogue signal being switched off means that the beacon of our radio and televisual communications will cease to penetrate space in quite the same way, almost like us turning off the porch light – so if there is other intelligent life out there – chances are they’ll never hear or see us anyway!

Throw into that the notion of the big bang reversing and the universe being like a massive diaphragm and then translate that into creation mythology and the cycle of death and rebirth and you end up with Adam and Eve effectively returning to Eden and life being gradually snuffed out.

Of course when you run these big ideas through an emotional process such as a dramatic script, it takes on a much simpler humanistic resonance and really becomes as much about the degradation of the human psyche and its destruction at the hands of inner demons, or – as I see it – the slow painful death of a profound relationship.

What did you want to achieve by making this film?

I think what anyone wants… to tell a particular story. The actual narrative is somewhat straightforward: a couple is driven apart by forces within and without the relationship. What interests me most in stories is the use of archetypal characters, that are rounded and hopefully avoid cliché, characters we can all relate to on a simple and primal level.

The backdrop of armageddon is a somewhat grandiose externalisation of what the characters are going through on a personal level, and of course there are mythical (or biblical) overtones galore too, which lend a sense of gravitas. Religious or not, it’s hard to avoid the universality of early social mythologies. Whether it’s Pandora or Eve, Lucifer or Prometheus, we are all imbued with an almost innate ability to recognise the grand themes of good and evil, temptation, sin, guilt and so on.

The platform for the narrative was always going to be a restricted one. It needed to be, both for budgetary reasons and for the simplicity of the story. A singular location and a small cast were dictated by the story, and for me the single most important thing was to eke out natural and powerful performances, performances that had very little to prop them up; no fancy camera-work and very little in the way of props or costume or locational variety. There was nothing to hide behind, either behind or in front of the camera, and that was the biggest challenge for all of us – to bring some truth to what we were trying to say.

The End of the World genre is a well-trodden one. What did you want to bring to it that hadn’t been expressed before?

It is indeed well-trodden. With the lead up to 2012 and the Mayan ‘end of days’, there was obviously an increase of such stories in this well saturated market. For me, The Devil’s Bargain pretty much addresses this trend, highlighting that actually it’s nothing new. Mankind has been spotting harbingers of doom and destruction as early as man discovered he was mortal. The middle ages was rife with it, and it wasn’t new then! Change has always been feared, and precipitated hysterical predictions of the end.

With that in mind, it seemed appropriate to look back to a time in the not so distant past that seemed, on the face of things, very familiar. 1974 was a time of recession, austerity, weak government, perennial troubles in the middle east – you name it. Setting this film in the past avoided any predictive sense to our apocalypse. It immediately renders it immune to becoming anachronistic because it isn’t a direct play on our current fears of annihilation and destruction. Whether you decide that it’s a parallel reality in which the world ends in 1974, or an acknowledgement that it isn’t real (since the world didn’t end!), what it really does is open up a bigger theme of the piece, which is that any end is also a beginning. Most ‘end of the world’ stories are necessarily filled with despair, and a mourning for what has been lost. But there has to be hope. Hope in the face of utter annihilation! Now that’s something different.

There’s plenty of nudity in the film – did this make the casting of the film more challenging?

Oddly enough, not really. But yes, there is a lot of nudity in the film, as necessitated by the story. And I think that’s the key point. It wasn’t gratuitous. There’s some in the first half, but from halfway onwards basically everyone is totally naked! I’ve worked with Jonnie Hurn several times, and knew that he was no prude when it came to doing what needed to be done. Dan Burman had come from being a link in the Human Centipede 2, so after that ignominy I think he was up for anything as long as it served the story. Chloe Farnworth is another dedicated actor, and wasn’t particularly shy about it. It’s to all their credit that they did such a great job with nowhere to hide.

I’m not sure they were quite prepared for the fact that using a pinhole (see more below) meant that because the angle of view is so wide the camera had to be extremely close to the actors, which is invasive at the best of times, but can only be more so when naked. But generally there were no hidden traps in the script – it was explicit where and when (most of the time) the characters had to be naked. I really can’t speak for them (and I’m sure they hid well the inherent challenges!) but it did seem to become ‘natural’ very quickly on set.

The look of the film is particularly impressive given the budget. How did you achieve this particularly unique vision?

The vast majority of the film is shot through a ‘pinhole’ adaptor, which is exactly what it sounds like. Instead of a typical glass lens on the front of the camera, we used a sealed cap with a pin-size hole in the middle. This means that you’re only getting a tiny amount of light to the camera sensor, which creates a very particular look. Effectively you have infinite (albeit not the sharpest) focus, which (in these days of DSLR shooting and ultra shallow depths of field) is a somewhat unfamiliar way of seeing the world. The pinhole fixes the camera at a perpetual wide-angle, which is as visually arresting as it is awkward to be restricted to! It also renders colours in a somewhat unusual manner, all of which conspires to produce an almost Super-8 quality of image. The opening scene is overtly Super-8 in a square ratio, and the remainder of the film, as it opens up into widescreen, plays off that.

So really, the look was something we were basically stuck with. There wasn’t a lot of latitude to be had, and we struggled for light if so much as one cloud floated in front of the sun! I wanted the film to have that retrograde look, almost like a moving ‘instagram’ (which seems to be very popular now!), to feel like it really is of the period in which it is set. My brief to Glen Warrillow, the Director of Photography, was to ‘float around as if you’re God, making a Super-8 home movie!’. It’s hopefully a look that wavers between voyeuristic and claustrophobic.

To be honest, though, the real work was (as it usually is) in post-production. I degraded the picture even further, adding sensitive light leaks at opportune moments, and letting the ridiculously talented JD Evans loose on a detailed sound design in tandem with a score that relied mostly on samples from wind harps! The film was shot in little more than twenty four hours, over four days, but spent months and months in post.

You’ve chosen to release the film yourself. Was this a conscious decision from the start?

This film was always going to be a little left field. It’s shamelessly ‘out there’. I am pretty confident that it’s the first feature to have been basically shot all through a pinhole (with the exceptions of the opening scene and a few still images). It has ‘underground’ written all over it.

We were very aware that the growth in online streaming and VOD has leapt forwards over the last few years, and really is inevitably going to be the first port of call for independent films in years to come. I don’t want to make a film that sits around waiting for a mainstream distributor to slot it into their catalogue and push out a limited release, only for it to be overshadowed by the bigger releases.

To me, what matters most is a direct link to the people that watch the film. The internet provides us with effectively a world-wide release and makes the film available to anyone with a half decent internet connection. In an age where only the big studio films are getting time at the multiplexes, and independent films are championed only by small cinemas in big cities, an online release is almost the equivalent of a cinema release! I truly believe, despite the mess that the industry seems to be in (any state of flux looks like a mess for a while!), that there is a quiet revolution happening in film.

I like the idea that we can get closer to the public as filmmakers, through social media interaction and online self-distribution. This trend has its naysayers, sure, but the proof of the pudding will always be in the eating! With technology becoming smaller and more affordable, and almost any dark room having the potential to be a screening room with Hi Def picture and surround sound, why shouldn’t we take films on tour again – like they used to with battered film prints, this time with a Bluray or DCP?!

What is it about the horror genre that particularly appeals to you?

There is little in the world more primal, emotionally, than fear – fear of pain, death, loss, the unknown etc. We are governed by the conflict between the great polar opposites of love and fear, and you can’t have one without the other. Horror is now such a wide ranging genre that it is usually further categorised into sub-genres! I have always had a soft spot for horror, mostly because I just think that whether it is tension preceding an horrific kill in a slasher or the unbearable angst of a psyche unravelling, these stories pack a real simple punch. They get you where it hurts, and you come out the other side thrilled and stronger. Danger is exciting. Who doesn’t like roller-coasters? We all know the odds of it flying off the track and killing dozens of people are minuscule, but we all love to entertain that possibility and revel in the adrenaline rush. I guess, on a simple level, I think that looking into the darkness is as educational for the human soul as an experience can be – however that darkness is manifested. And hey, for the most part, it’s fun too!

What’s next for you?

Ian [Manson] and I have a raunchy dark comedy script called ‘Skinny Buddha‘ that is raring to go. We have a great cast lined up already, and hope to get cracking in early 2014. It’s very different from anything I’ve done, but then so is everything I’ve done so far! I have no real interest in retreading familiar ground as a filmmaker, even if I do lean in the horror direction quite often!

Is it true you have a zomcom, SHED OF THE DEAD, in the pipeline?

Ha… yes indeed. Or a ‘zombedy’, as I like to call it! Different again, it’s a mad fun romp involving… well, zombies and a shed. It promises to be a lot of fun, and I can’t wait to get further down the road with it.

Be the first to comment