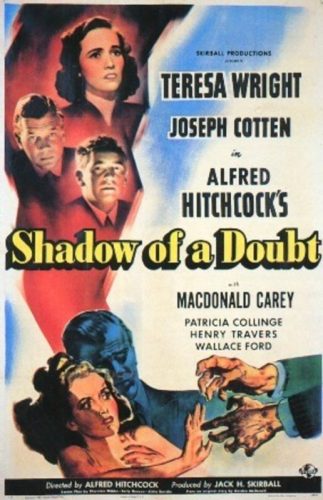

Shadow Of A Doubt (1943)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Alma Reville, Gordon McDonell, Sally Benson, Thornton Wilder

Starring: Henry Travers, Joseph Cotten, Macdonald Carey, Teresa Wright

USA

RUNNING TIME:112 min

AVAILABLE ON DVD

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: on the train to Santa Rosa carrying Uncle Charlie, playing a card game (and having a potentially-winning hand – a full house of spades) with a couple, with his back to the camera on the left side of the frame.

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

In a city, a man is found by the police but eludes them after a chase. Meanwhile, Charlie Newton is a bored teenager living in the idyllic town of Santa Rosa, California. She wants her Uncle Charlie to come and shake things up, and is about to ring him, but then receives the wonderful news that, as if by telepathy, her mother’s younger brother is coming for a visit anyway. Uncle Charlie arrives, and soon charms the family, but Young Charlie finds it strange that he cuts out a story in the local paper and takes it upstairs with him, a story she discovers is about a man who marries and then murders rich widows called the Merry Widow Murderer….

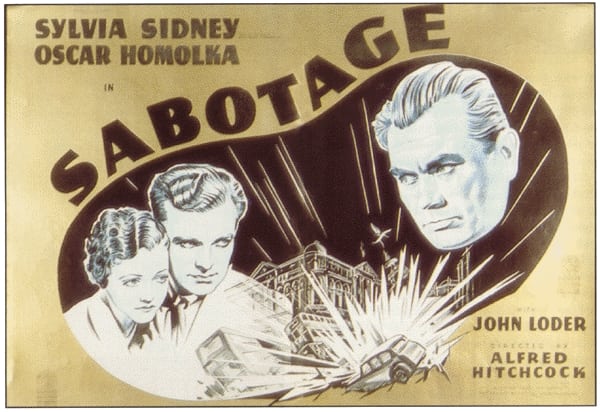

Hitchcock often followed up a film with another of a rather different kind, which makes ploughing through his work constantly interesting. After the picaresque action, wide canvas and ever-present war background of Saboteur, Shadow Of A Doubt is a considerable contrast, a very talky, slow, down-to earth affair closer perhaps to Suspicion, except that Shadow Of A Doubt is a far more interesting, psychologically complex and, yes, believable affair. No showy set pieces here: instead we have a detailed portrait of a cosy small-town Americana [Hitchcock totally shaking off all signs of his British background in a film which really seems like it was directed by an American] into which evil gradually inserts itself. Nothing much happens for quite a while in it, which means that this film may not impress too much upon first viewing. I certainly needed further viewings of this quiet, leisurely picture for me to realise it as the classic it is, and with successive watches you can more appreciate the clever detail in almost every scene, how totally real its environment seems, how good a portrayal of a psychopathic killer it is, and how disturbing the relationship between the two main characters is. For a start, this must be one of the first films to show a killer as a positive fantasy figure in someone’s eyes. I still don’t think it reaches the heights of the very best of Hitchcock, but it’s certainly one of those films that gets better the more you think about it.

David O’ Selznick continued to loan Hitchcock out for a huge profit, and the next production was again to be overseen by Universal, the producer being Jack Skirball. Hitchcock flirted with the idea of remaking Gaslight but was wary of costume dramas and its similarity to Suspicion, and a curious tale about a mad ventriloquist who commits bigamy, kills one wife and mistakes his second for the first [some ideas from this seem to have ended up in Vertigo]. One day the head of O’ Selznick’s story department Margaret MacDonell mentioned that her husband Gordon, a novelist, had an idea for a story he’d not yet written down. It was inspired by a mass strangler in the 1920’s called Earle Leonard Nelson and asked what would happen if a guy like that hid out with his family. Hitchcock heard about it, bought a nine page outline which he discussed with the couple, and the film was underway. Playwright Thornton Wilder wrote the first script, to which novelist Sally Bensen and actress Patricia Collinge, who played the mother in the film, added some lightness and humour. Though interiors were usually still in the studio, Hitchcock insisted on filming most of the many exteriors on location, and shot most of it in Santa Rosa, even using locals as cast members [notably the girls playing young Ann and Charlie’s friend Catherine], extras and advisors. Hitchcock wanted William Powell and Joan Fontaine in the two lead roles, but Fontaine was committed to another production and MGM wouldn’t loan out Powell. Joseph Cotton and Teresa Wright came on board. The production proceeded with no trouble, perhaps one of the reasons why Hitchcock often called it his favourite of his films [he also often named The Trouble With Harry]. It was only a minor success at the box office though.

Shadow Of A Doubt opens with a shot of Uncle Charlie lying on his hotel bed, for all the world looking like a vampire, and come to think of it there are parallels with some vampire tales, especially Dracula, in this story. Charlie flees from some cops who are observing him, the chase mostly shown aerially, giving us a great camera pan from looking down on the tiny figures of the two cops to catching Charlie, in medium shot, observing them and casually smoking a cigar. The film then adopts a more methodical pace as we switch to Santa Monica. Young Charlie is your archetypal teenage girl on the verge of adulthood who yearns for some excitement, her younger sister Ann and younger brother Roger are cute know-it-alls, her mother Emma just never shuts up, and her brow-beaten father Joseph’s only enjoyment seems to be talking about murder with his weird neighbour Herbie. Their increasingly morbid conversations about how they would kill each other [developed from some scenes in Suspicion] don’t at all advance the plot, but do work as an amusing counterpoint to it [despite their obsession with murder, they’re unaware one could be happening right under their noses]. There is actually a huge amount of chat from everyone in this movie, which seems largely set during breakfast and dinner for a while, and a couple of scenes could probably have been removed, but the dialogue is so sharp, the performances so natural [sometimes the cast speak over each other, more in the manner of a Robert Altman movie], and the overall situation so intriguing that the film easily gets by.

We know Uncle Charlie is the Merry Widow Murderer right from the offset, Hitchcock, as he often did, preferring suspense over surprise, and every now and again Joseph Cotton subtly changes the tone in his generally warm, kindly voice to an emotionless, almost monotone one. Combined with some really creepy looks, the result makes him very chilling. His scariest moment is when he talks about fat, greedy widows at dinner with truly disturbing hate. It’s an outstanding performance from Cotton, probably his best. His character does sometimes seem to want to reveal his true colours in public too much, and the odd scene where he does this comes across as a little contrived, but then this is a lunatic who has a hatred for widows and strangles [Hitchcock’s favourite method of killing] them, so rational behaviour can’t always be expected. The tension does begin to rise when Young Charlie realises who her uncle is and that he knows this. Eventually he does try to kill her, but in ways nobody else would notice. The climax on a train is possible a little rushed and its end rather unconvincing, but the neat wrap-up nicely ironic. Sometimes withholding secrets is a good thing, and nice small-town Americana can be protected. An interesting thing about the story to this movie is that, throughout its course, only four of its characters seem to know some of what is really on and only three do at the end.

It’s been debated whether Young Charlie, who is certainly in love with Uncle Charlie in some respect, actually has incestuous desires towards him or not. I think it’s obvious: just look at some of her body language. In any case, she’s constantly shown as a kind of double of her uncle – she’s even first seen lying on her back on her bed in the same way as he is introduced – and he represents a possible dark side to her nature. She appears to seriously flirt with evil until Jack Graham the cop shows an interest in her. His character has been called unnecessary, but I disagree entirely despite him not being played too well by Macdonald Carey. He represents normality and ‘healthy’ desires, and Young Charlie eventually realises that this is the world for her. The first time the garage door is closed on Young Charlie, it’s just after she’s received a declaration of love from Jack. Part of Uncle Charlie’s attempted murder of her is implicitly inspired by sexual jealousy, not just fear of discovery. He sees his power over her slipping as she moves towards a more natural sexual/romantic relationship and away from their ‘connection’. The one bit concerning this that doesn’t quite work is an awkward jump from Charlie and Jack laughing after her friends have caught her out on a date with him after claiming to have a sore throat, to Charlie’s disbelief that Jack suspects her uncle of being a murderer. It looks like some footage is missing. It doesn’t spoil enjoyment of Teresa Wright’s expertly detailed performance of an infatuated girl betrayed by grim reality and having to deal with it.

Aside from the device of showing people dancing which visualises Uncle Charlie’s obsession with Franz Lehar’s Merry Widow Waltz, Hitchcock’s direction is quite unobtrusive in this film, though the photography of Joseph A. Valentine, who did such fine work on Saboteur, is often striking in the way he gradually has characters surrounded more and more by darkness. Composer Dmitri Tiomkin would write three other scores for Hitchcock and they would all be better than this one, but his constant twisting of Lehar’s waltz to sound menacing is cleverly done, there are some good suspense passages and a nice love piece for Jack and Charlie. Piano is well used in some of the more intense moments. Shadow Of A Doubt remains a skillful, intelligent and thought-provoking work from the Master Of Suspense, perhaps lacking some of the fireworks that would make it truly thrilling, but memorable nonetheless. It was adapted for radio five times and was remade as Step Down To Terror in 1959 and in 1991 as a TV movie of the same title. 2013’s Stoker was also heavily inspired by it.

Be the first to comment