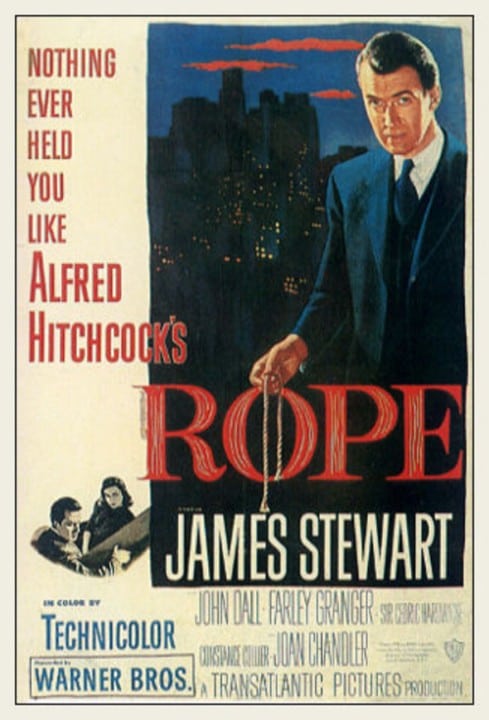

Arthur Laurents (1948)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Arthur Laurents, Ben Hecht, Hume Cronyn, Patrick Hamilton

Starring: Constance Collier, Farley Granger, James Stewart, John Dall

HCF REWIND NO. 217: ROPE [US 1948]

RUNNING TIME: 80 min

AVAILABLE ON DVD

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: a) in the opening credits, walking beside a woman by a fire hydrant holding a newspaper (b) Hitchcock’s trademark silhouette/caricatured profile can be seen briefly but blurrily on a flashing red neon sign seen in the far distance through the apartment window. His recognizable profile is above the word “Reduco” – the fictitious weight-loss product also in Lifeboat

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Inspired by conversations years earlier with their teacher Rupert Cadell, Brandon Shaw and Phillip Morgan strangle to death a former classmate, David Kentle, in their apartment, committing the crime as an intellectual exercise, trying to prove their superiority by committing the “perfect murder”. After hiding the body in a large antique wooden chest, Brandon and Phillip host a dinner party at the apartment. Among the guests are the victim’s father, aunt, fiancée and Rupert, while Brandon even uses the chest containing the body as a buffet table for the food….

So how’s this for experimentation? In 1947 [when it is often considered films were more restricted than they are now though in some ways I don’t think that was the case], a filmmaker, and a filmmaker whose work was considered ‘commercial’ more than anything else, decides to make a film which would abandon many standard filmmaking techniques in favour of lengthy ‘unbroken’ scenes where shots would run for up to ten minutes without cuts and even the transitions between shots would be partly disguised by the camera zooming into something dark like a suit jacket, almost giving the impression that you are watching real events on screen. Rope is a fascinating technical experiment that I doubt anyone would want to do today, and it’s very praiseworthy for that reason, though to be honest it doesn’t totally come off and work as a film. There is a sense that Hitchcock was focused on the technical side of things more than anything else , leaving the resulting picture feeling a bit arid and dry, and it’s certainly not as enjoyable as his later ‘filmed play’ Dial M For Murder, though Hitchcock’s first film in colour is still full of interest as nearly all of Hitchcock’s films are and is still definitely still worth a watch.

Rope was Hitchcock’s first production for Transatlantic Pictures, the company he set up with Sidney Bernstein to make films where he had total control. Based on Patrick Hamilton’s play Rope’s End, inspired by the 1924 Leopold-Loeb case where two men killed a 14 year old boy for kicks, Hume Cronyn’s treatment was turned into a screenplay by playwright Arthur Laurents, though as usual this was in collaboration with Hitchcock. Some characters were changed and the homosexual aspect – in the play not only are the two killers gay but so is their old teacher Rupert – made far more subtle, though during production the film was widely known as the film about “it”. Black humour was also added and the murder now shown. The way Rope was shot meant that the walls of the set were on rollers and could silently be moved out of the way to make way for the camera and then replaced when they were to come back into shot. Prop men constantly had to move the furniture and other props out of the way of the large camera, and then ensure they were replaced in the correct location. A team of soundmen and camera operators kept the camera and microphones in constant motion, as the actors kept to a carefully choreographed set of cues, which James Stewart hated so much he vowed to never work with Hitchcock again. The camera dolly ran over and broke a cameraman’s foot, but to keep filming, he was gagged and dragged off. Another time, a woman put her glass down but missed the table, so a stagehand had to rush up and catch it before the glass hit the ground. Both parts were used in the final cut. Though the last five reels had to be reshot due to being too ‘bright’, Rope was made quickly and cheaply, and made its money back despite hardly being popular and being banned in some states.

Rope had a great trailer which was a prologue showing a man and a woman, who are David and Janet, walking in the park and planning their future together while Stewart’s voice says: “That’s the last time she ever saw him alive”, though the opening shot of the film proper, which shows in close-up the last few seconds of the strangulation of David, must have still shocked audiences of the time. Though nothing is spelt out, the killers are clearly a gay couple, something which would no doubt annoy the PC morons if the film was made today, but we’re hardly talking about Diamonds Are Forever’s Mr Wint And Mr Kidd here. Aided somewhat by the facts that Farley Granger was bisexual and John Dall and Laurents were both gay [and in a relationship which only Hitchcock knew about at the time], they feel like a genuine couple and are certainly not mocked by the screenplay. Unlike the play which didn’t show the murder and therefore kept the audience guessing as to whether there really was a body in the trunk, the film is more challenging because there are times you want Brandon, who is clearly the dominant half of the couple, and Phillip to get away with it. You have to admire their gall in killing someone, then inviting round some people which include relatives of the dead man and his fiancée, trying to get the fiancée and her ex-boyfriend back together, and using the trunk containing the victim’s body as a table!

Being basically a play, the film soon resolves itself into a series of dialogue scenes. Some of the best involve the verbose Mrs. Atwater, who is always forgetting whatever play or film she’s seen [one of them seems to have been Hitchcock’s Notorious] and, examining Phillip’s hands, tells him they will bring him great fame in one of quite a few lines which have double meanings that only the two killers and the audience would pick up on….well, except for Rupert, who obviously suspects what his former pupils have done quite early on because of Phillip’s obvious nervousness and his denial of having killed a chicken when Rupert had seen him kill several. The clues don’t pile up in a suspenseful manner though and the whole film just isn’t as tense as it should be. The camera gracefully moves around, eavesdropping on various conversations and creating tension out of the odd act like the putting of the rope used to kill David in a kitchen draw being shown through a swinging door, and but in the end filming what is largely a dialogue piece set in one room in this fashion just doesn’t help it much and merely adds to the impression that we are watching a play. Hitchcock would have been better off using the style with a more traditional suspense thriller. Something that remains hugely impressive, so much so that this time I had trouble taking my eyes off it, is the extraordinary backdrop of New York seen out of the window, replete with detailed models of the Empire State and the Chrysler buildings, smoking chimneys, lights coming on in buildings, neon signs lighting up, clouds changing position, and the sunset slowly unfolding as the movie progresses. Incidentally, events don’t entirely occur in ‘real time’ as they initially appear to be in, with the story still jumping forward at times.

Rope contains perhaps the most obvious continuity error in Hitchcock’s filmography – a cut hand wrapped in tissue being fine a couple of minutes later – while you can see chalk marks on the floor in one shot clearly marking where something is intended to be in the next scene. The camera also wobbles a bit at times, though in these days of that horrible non-cinematography known as ‘shakycam’ the camerawork is graceful and elegant. Rope also suffers from some serious issues of confusion. Early on, Rupert gives a speech where he says how murder can be a good, justifiable thing and how superior people have a right to kill inferior ones. This is clearly the philosophy that led his ex-students to kill. However, at the end, he gives a lengthy speech [partly written by Ben Hecht] where he’s angry at Brandon and Phillip for perverting his beliefs. We’re not told exactly how though. Rupert’s philosophy clearly legitimises murder, unless of course Rupert was merely winding people up earlier? In any case, it’s a bit muddled, and if you think about it also makes Rupert the true villain of the piece, which is most intriguing but clearly not intended. They should also have kept Rupert gay, though I guess that would have been too much for the censors [who had no trouble with killers being gay so long as it wasn’t spelt out], and there’s no way that Stewart would have wanted to do the part either. Funny how the bisexual Cary Grant and the homosexual Montgomery Clift [though both were secrets at the time] were considered to play Brandon and Phillip and not cast because it was thought audiences would not accept them as gay.

Stewart, clearly not enjoying himself, feels a bit awkward in his first Hitchcock film, while Dall and Granger are very good as the killers, Granger especially effective in his awkwardness. You feel the character could give himself away to everyone at any minute. Constance Collier as Mrs Atwater is clearly nervous on screen and her slurring is obviously not due to the character drinking. The music theme by Francis Poulenc, played on the piano by Granger a couple of times, is incongruously jaunty but in a nicely ironic way, and there is some superb use of sound, especially in the climax where Rupert fires his gun out of the window to attract attention and you hear various sounds wafting in. In the end though Rope feels a bit empty. It aspires to be somewhat intellectual but falls short because of inconsistent writing, while it’s not really much fun either. It’s more a film to study, and on that level is certainly worthwhile. It was unavailable for decades because its rights, together with those of Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Trouble with Harry, and Vertigo, were bought back by Hitchcock and left as part of his legacy to his daughter Patricia. All five were re-released theatrically in 1984 after a 30-year absence. The Leopold-Loeb case also inspired 1859’s Compulsion and the very accurate Swoon [1992], while the 2002 R.S.V.P. borrowed several key elements from Rope and even had the film discussed.

Be the first to comment