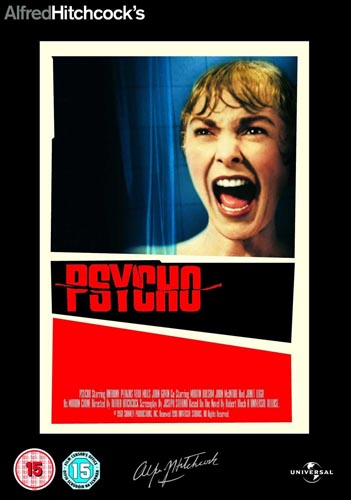

Psycho (1960)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Joseph Stefano, Robert Bloch

Starring: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, John Gavin, Vera Miles

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME: 109 min

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: Wearing a large cowboy hat and seen through Marion Crane’s office store-front window, loitering or standing on the sidewalk, as she returns to her Phoenix real estate company after a lunchtime ‘quickie’ in a cheap hotel with Sam Loomis

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Marion Crane works in a realtor’s office in Phoenix, Arizona. She and her boyfriend Sam Loomis, whom she meets for secret rendezvous during her lunch hours at a hotel, can’t get married due to Sam’s debts. When a client comes in with $40,000 in cash to buy a house, her boss instructs her to deposit the money in the bank. After some contemplation, she steals it and leaves Phoenix for Fairvale, California, intending to give it to Sam. After hastily exchanging her car and encountering some suspicious cops, she takes a wrong turn and finds herself at the Bates Motel, a remote lodge that has recently lost business due to a diversion realignment of the main highway. The youthful proprietor Norman Bates seems nervous but friendly….

So at last here we come to it, easily the most famous, the most popular, and the most analysed film that Alfred Hitchcock made. It may very well be one of the most important and influential films in world cinema, and, the same year’s Peeping Tom and certain much older movies like The Spiral Staircase notwithstanding, is definitely the film that most inspired the whole slasher subgenre. It’s a film that even today you constantly see echoed. You’re never far from something which riffs on Psycho’s shower killing, which just seems to turn up all over the place. Every time I switch on the UK Living Sky channel I’m confronted with Imperial Leather advertisements which are clearly inspired by the scene, and this is 53 years after the film was released!

As to whether Psycho, which is in part an even more twisted reworking of Vertigo [think about it- a man is obsessed with a woman beyond death] is actually Hitchcock’s best film…well that’s something I disagree with, though some of that may be due to the fact that its effect has been a bit diminished over the years because everything from its plot to many of its scenes have been copied over and over again. Now I’m certainly not saying it isn’t a great film. It is. My review will be mostly full of praise, and there are certain elements of the film which are simply superb. Maybe it’s just a personal thing, but Psycho just doesn’t quite get to me the way Rear Window and Vertigo do, I don’t feel it quite reaches the brilliance of those two films, and there a few other Hitchcock films that I prefer to watch. Again, I’m not saying that Psycho isn’t very good. I’m saying that it is. I’m just saying that overall I believe it’s slightly less impressive than its reputation. In fact, and I reckon I’m going to shock you now [well, this is Psycho we’re talking about], but I believe that Brian De Palma’s semi-remake of Psycho, Dressed To Kill, is probably more effective in some ways. If you analyse both films, Dressed To Kill will probably come up short – for a start, it doesn’t have the depth of characterisation of Hitchcock’s film – but in what it does, and the way it does it, the 1980 film sometimes works better to my eyes, though of course, like probably half of the horror movies made since 1960, it wouldn’t even exist if Hitchcock hadn’t made Psycho.

Hitchcock wanted to film Cecil Henry’s novel No Bail For The Judge, about a female barrister whose father may have killed a prostitute. Vertigo’s Samuel Taylor wrote a script, but the proposed star Audrey Hepburn turned it down on account of a rape scene. Wanting to make a ‘smaller’ and more horror-type picture, Hitchcock turned to Robert Bloch’s novel Psycho, inspired by the real life murderer Ed Gein, and got his secretary to buy up copies to preserve its surprises. A horrified Paramount turned it down, so Hitchcock made the film independently with his own money and with mostly his TV series crew. He got Joseph Stefano to re-write James P. Cavanagh’s faithful-to-the-novel screenplay, notably extending the first section of the film concerning Marion’s flight, removing a romance between her sister Mary and Sam, cutting ‘cheating’ scenes of Norman and Mother, and making Norman more likeable. Hitchcock tested the fear factor of Mother’s corpse by placing it in Janet Leigh’s dressing room and listening to how loud she screamed. Mother was actually voiced by three women, their voices mixed together. Title designer Saul Bass later claimed he shot the shower murder, and did shoot the stairs death while Hitchcock was ill, but Hitchcock reshot it. As he was finishing the film, and before he heard Bernard Herrmann’s score, Hitchcock panicked, thinking Psycho was poor and that he should cut it down into a TV episode, but Herrmann talked him out of it. Hitchcock was so pleased with the score that he doubled Herrmann’s salary. His wife Alma Reville spotted that after Marion was supposedly dead, one could see her blink, so the shot was cut. Aided by one of the best trailers ever, a jovial Hitchcock taking the viewer on a tour of the main house set, and almost giving away plot details before stopping himself, Psycho was a box office sensation, though the critics mostly hated a film that was so ahead of its time.

For the film’s first scene, Hitchcock originally planned an elaborate camera movement to take the viewer closer and closer towards the window of the room that Marion and Sam are sharing during her lunch hour, but costs ended up negating this and instead we get some dissolves and even a bit of slight jerking about with the camera, suggesting it was done in a hurry, though of course compared to what you often see today it’s really smooth. Now to really appreciate Psycho you have to put yourself in the mind of a 1960 cinemagoer, and no 1960 cinemagoer would have expected to see a film open with an unmarried couple sharing a bed and having obviously just had sex – films were normally very subtle at suggesting such a thing with even the dalliance between Cary Grant and Eve Marie-Saint in the previous year’s North By Northwest cutting to the couple getting off the train after the event – and Janet Leigh and John Gavin playing much of their dialogue scene horizontally. There’s a very voyeuristic and, yes, erotic feel to it, and even though we’re right at the beginning of the picture it’s proof that the 60 year old director was trying something new, fresh and modern. This film isn’t played out in a lush Technicolour fantasy world of big stars and pretty locations, it’s played out in a very real, actually rather drab world, albeit one that will soon acquire some Gothic tropes. Of course it’s worth mentioning here that, three years before, Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man had taken place in a world not entirely different, though less determinedly ‘adult’, and audiences weren’t perhaps as ready for that from Hitchcock as they were by 1960.

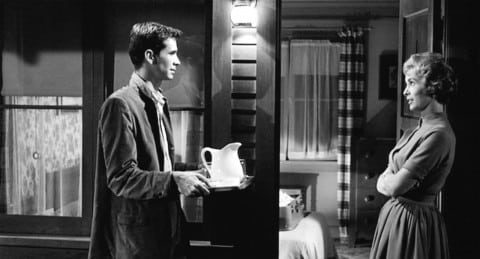

Any viewer in 1960 without prior knowledge of the book would assume that Psycho is going to be primarily about a woman who absconds with some money. From the point of view of someone who knows about the film even if he or she hasn’t seen it, much of the film’s first third seems a bit like stretching out the build-up just for the sake of it, what with Marion encountering a suspicious cop, exchanging her car and imagining people talking about her as Herrmann’s frantic main title music plays over and over again, but first time viewers back in 1960 who would mostly have been ignorant of what was going to happen wouldn’t have felt this way. They would have really felt that Marion was the heroine, and that she would last the duration of the film, even when she finally arrives at the Bates Motel, amidst a furious rainstorm. The owner, Norman Bates, seems a little shy and awkward but is basically quite a nice, even sweet, fellow. The lengthy conversation between Norman and Marion is fraught with understated tension, strong writing and clever acting. Perhaps Norman opens up more to Marion than he has done to anyone before? In any case, it’s not long now before Norman peeks at her undressing through a hole in the wall, and someone, probably Norman’s overly strict, unseen Mother, stabs her to death in the shower. What struck me this time watching the film is how much black humour is in some of Stefano’s lines [“Mother isn’t quite herself today”], though even funnier is that after the film’s release Hitchcock received an angry letter from the father of a girl who refused to have a bath after seeing Les Diaboliques [this superb French thriller was a major influence on Psycho] and now refused to shower after seeing this film. Hitchcock sent a note back simply saying: “Send her to the dry cleaners.”

The most famous murder scene in cinema history, which of course owes much of its effect to Hermann’s screeching violin slashes [yet Hitchcock actually didn’t even want music in the scene until Herrmann played him the scene with his music] consists of 77 different camera angles and 50 cuts, which I suppose doesn’t seem like much of a big deal when many films today, especially action ones, use loads of quick cuts and angles to sometimes nauseating effect, but is still incredibly effective in suggesting extreme horror and brutality. Hitchcock claimed that we never see the knife enter flesh, but actually you do briefly see it do so twice, though it’s easy to miss. Blood is still kept to a minimum, the only shots of the chocolate syrup that was used for the scene being of some of it going down the plughole and after the killing when Norman is cleaning up after Mother. There are few better examples of how to manipulate a viewer in the scene where Norman is pushing Marion’s car into the swamp by the motel. The car seems to not want to sink all the way in, and we are actually on Norman’s side.

The rest of the story follows Sam, Marion’s sister Lila, and P.I. Milton Arbogast investigating the disappearance of Marion, and eventually unveiling a plot twist which must have truly shocked people in 1960 though has been imitated so much since one can probably predict it nowadays even if you don’t know it prior to seeing the film. Watching Psycho again, it’s notable how dialogue heavy the picture is, and how the film actually gets less violent as it goes on. The second murder, despite being extremely disorientating what with the aerial shot of Mother [the ultimate of Hitchcock’s many and usually not very nice Mothers] attacking and the dizzying simulation of the victim falling down the stairs, shows very little actual stabbing, while nobody at all gets hurt in the climax, which comes across as being a bit rushed and is slightly unsatisfying despite its oft-copied swinging lamp. I’ve always felt that Psycho could have done with a couple more suspense scenes. However, by far the weakest aspect of Psycho is its penultimate scene where a doctor explains everything to Sam, Lila and the audience. Apart from one detail which could have been put in another way, what we hear is rather redundant and treats the audience like fools. The scene was obviously thought necessary at the time, and at least it’s followed by a brilliant final moment afterwards.

John L. Russell’s cinematography starts off very naturalistic and gets more and more film noir-like as the film goes on. Hitchcock makes great and, considering the story, appropriate use of mirrors in a tale where everyone, even the most minor character, seems to have something to hide, but now it’s time to praise the astonishing performance of Anthony Perkins as Norman, by far the best portrayal of a psychopath in film, and one that makes Psycho worth watching again just to study his understated, yet immensely detailed, acting [and isn’t it also interesting, considering what Hitchcock’s next film would be, how obsessed Norman is with birds?]. Just look at the way that, for example, he seems to sometimes look at the ground, or clench his jaw, or almost constantly scoff candy [Perkins’ idea]. His most chilling moment for me comes after Arbogast leaves him and Norman is still bristling over the detective’s comments about being fooled by a woman and pressing the issue about speaking with Mother. The conversation scene is expertly written and played by both Perkins and Martin Balsam with great subtlety, but then Arbogast goes. A glaring Norman turns to watch Arbogast leave, leans against the office window, then lowers his eyes and seems to be looking at the ground just in front of where the car would be. Then definitely after Arbogast exits, Norman smiles – first to himself, then to the world – and then he all but breaks into a laugh…after which it’s back to smiling again. I guess that Mother had just turned up. Janet Leigh and The Wrong Man’s Vera Miles are fine in their roles [John Gavin, playing Sam, is a little bland if still fairly natural] but Psycho really is Perkins’ show.

Herrmann’s music, scored entirely for strings, has that pulsating, and oft-repeated in the first third, main title theme, and those famous violin screeches, but is throughout a sublime exercise in psychological enhancement of a story and images, a dark, incisive masterpiece in its own right. As usual, Herrmann uses much repetition of simple phrases, but to clever psychological effect. Take for instance an early scene where Marion is looking at the money on her bed. A scene where nothing is happening is made suspenseful by the nervous violin flourishes which seem to musically describe Marion’s state of mind. When Norman later talks to Marion about Mother, the discordant scoring is of such bleakness it seems to let us get inside Norman’s head for just a while. The score really gets under the skin like few others. Every now and again, it also has a gloomy sadness to it, which leads to what I think is the real key to Psycho’s effect and why it will last forever even if it has some flaws, at least to this critic, and isn’t quite Hitchcock’s ultimate masterpiece to his eyes. Hitchcock and Stefano get the audience on the side of Norman, and make us feel really sorry for him. The final scene of Norman lost in his own little world is not just very unsettling, it’s very sad and pathetic. After all, he didn’t really commit the murders, did he? And don’t: “we all go a little mad sometimes?”

THE LEGACY OF PSYCHO

21 years after Psycho, there was a surprisingly good sequel, Psycho 2, which was followed by the less impressive but still good Psycho 3 which also starred Perkins and which Perkins actually directed. Then came the muddled though interesting Psycho IV: The Beginning, a TV movie which was both a sequel and a prequel, and was written by Stefano. Gus Van Sant’s 1998 scene by scene remake remains one of the most pointless endeavours in motion picture history. Then 2012 saw Hitchcock, a sometimes fictionalised account of the making of Psycho. 1987’s Bates Motel, which had a cameo appearance from Norman though Perkins declined to play him, was a failed TV pilot spin-off which later aired as a television movie, but the 2012 TV series of the same title, soon to have its third series, is a major success. It deals with Norman’s teenage years, though is set in modern times. Meanwhile so many films have been influenced by Psycho, beginning soon after its release with Homicidal, that I could probably write three lengthy articles just listing the titles. Every time you watch a slasher film, from Halloween to more recent efforts like Scream, you can see Psycho in there somewhere, while of course Ed Gein influenced not just The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Silence Of The Lambs but the more true-to-life Deranged and Ed Gein.

PSYCHO AND THE CENSORS, AND THE GERMAN UNCUT VERSION

Unsurprisingly, the MPAA [US censors] had serious issues with Psycho. Most amusingly, they didn’t even like a toilet being flushed, considered to be such a horrible sight it was just not normally allowed, but because it was part of an important plot point in this film the shot was allowed to stay. They didn’t like the sexy opening, but when Hitchcock offered to reshoot the scene with some censors present, none of them turned up so the scene stayed. As for the shower scene, Hitchcock was asked to take some frames out because some of the censors insisted they could see one of Leigh’s breasts. Hitchcock held onto the print for several days, left it untouched, and resubmitted it for approval. Each of the censors reversed their positions: those who had previously seen the breast now did not, and those who had not, now did. Hitchcock agreed to make make cuts anyway but all he ended up removing was a shot of the buttocks of Leigh’s stand-in. In the UK the scene was shortened and a shot of blood on Norman’s hands removed.

Now this is where it really gets interesting. It’s been generally assumed that aside from the buttocks shot nothing else was cut from Psycho in the US and that the version that we have all seen since is uncut. Actually this isn’t true. German TV periodically shows a slightly longer version which has more of Marion undressing, more of Norman’s bloody hands, and two stabbings during the stair murder before the scene fades out. This means that the film was censored in a few places for release in most countries, though most of them probably just used the US print. It was though released uncut in Germany. Now if you don’t believe me, check out the link below to this Facebook page [as far as I can tell the only way outside of Germany you can legally view the footage] and you can see the cut footage on there.

https://www.facebook.com/AlfredHitchcockPsychoUNCUT

It’s astounding how even the Blu-ray releases are of the cut version. The question is, why? We’re not talking about something obscure here, we’re talking about the most famous film made by one of the most famous of directors, and just think how much money the studio and distributors could make, even if the footage is only 20 seconds or so. The only possible answer I have is that Paramount just isn’t aware of this, but none of the books on Hitchcock I have read mention it either. Let’s hope things change and we finally get a complete version.

Be the first to comment