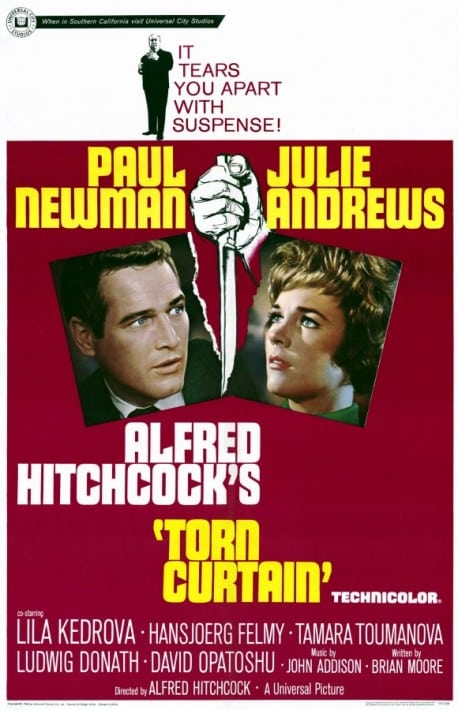

Torn Curtain (1966)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Brian Moore, Keith Waterhouse, Willis Hall

Starring: Hansjörg Felmy, Julie Andrews, Lila Kedrova, Paul Newman

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME: 130 min

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: In Copenhagen, sitting in the large Hotel d’Angleterre’s lobby entrance with a blonde-haired baby in his lap [which possibly wets itself], with his back to the camera. During the brief cameo, the music changes to resemble the famous ‘Hitchcock theme’ from his TV show, also known as Gounod’s ‘Funeral March of the Marionette’

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Esteemed American physicist and rocket scientist Michael Armstrong, currently working on an anti-nuclear missile project, is to attend a scientific conference in Copenhagen, but en route with his assistant and fiancée, Sarah Sherman, he receives a radiogram to pick up a book once in Copenhagen. The book contains a message that says: “contact in case of emergency.” He tells Sarah he is going to Stockholm, but she discovers he is flying to East Berlin, and, when she follows him there, finds that he has defected to the other side. Michael visits a contact, where it is revealed that his defection is in fact a ruse to gain the confidence of the East German scientific establishment so Michael can steal a formula consisting of anti-missile equations from their chief scientist Gustav Lindt….

“It tears you apart with suspense” screamed the posters for Torn Curtain, but they were definitely lying. Easily Alfred Hitchcock’s weakest film since To Catch A Thief, Torn Curtain partially seems like an attempt to bring a more realistic kind of spy story to the screen than the James Bond films and their many imitations which were flooding the screen at the time it was made, but it’s curiously flat for much of its running time, and certain films like The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and The Ipcress File had already done the more ‘down to earth’ espionage thing in a much better fashion. There are great touches throughout and the film isn’t exactly bad and is actually fairly enjoyable if you forget who its director is, but the latter is actually quite easy during some of the film as much of it just seems to lack the Hitchcock touch. The story should make for a really exciting film and its kind of subject matter had served Hitchcock very well in the past, but it just doesn’t come off nearly as well as it should, as if the director was disinterested in the proceedings. It’s little surprise to learn that he was going through a bad time while he was making it.

After Marnie, Hitchcock tried to set up a project he’d been passionate about for some time, a film of J. M. Barrie’s bizarre play Mary Rose about a woman who disappears on a haunted island and decades later appears having not aged a day. Then he considered another spy thriller from The 39 Steps’ John Buchan The Hostages, and a project called R.R.R.R.R. about theft set amongst the mechanics of a hotel, before becoming inspired by the notorious defection of British diplomats Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean to Russia in 1951, and especially from the point of view of Maclean’s wife. The dialogue in Canadian writer’s Brian Moore’s script was rewritten by Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall as the film was being shot, and Moore later successfully sued to get sole screen credit. Hitchcock was badly affected by the deaths of both George Tomasini, his editor since 1954, and Robert Burks, his cinematographer since 1951, during filming, and was unhappy with having Paul Newman [over Anthony Perkins and Cary Grant, though Grant turned it down as he was about to retire] and Julie Andrews [over Eva Marie Saint] imposed on him by Universal, not getting on with Newman and his method acting at all. Hitchcock couldn’t even get his preferred ending, of the formula being thrown away, on to the screen. Then he fell out with composer Bernard Herrmann when the latter was both unwilling and probably unable to write the ‘modern’ style, ‘pop’ influenced score that, under pressure from the studio, he had to ask for, and sacked Herrmann when Herrmann played him what he’d written. He was so displeased with this film that he decided to not to make a trailer with his appearance in it as he had done for some time, though, largely due to the current popularity of screen and TV spies, the film did do decent business.

Torn Curtain really takes forever to get going, taking everything at a lumpen pace which may have been fine if we’d been given a chance to care about what’s happening, particularly poor Sarah, who finds that her fiancée [there was little fuss about a couple being introduced in bed together this time around!] is actually a traitor and is defecting to the other side. Andrews actually acts her character’s torment quite well, but there’s no chemistry between her and Newman and it’s all very cold and distant. With the emotional centre of the film hardly working, it’s down to the spy stuff, but the only really interesting thing about the first third of the film is how striking its visual change is, the early scenes of bright, vivid colours changing to drab greys, greens and browns once the scene switches to behind the Iron Curtain. Eventually we get a half-decent set piece when Michael evades a pursuer in a museum, all we hear being the sounds of the footprints, and then the highlight of the film, which is Hitchcock’s longest murder scene, and clearly the scene he had most interest in. He wanted to show how hard it actually is to kill someone, so when Michael and a farmer’s wife have to kill Gromek, Michael’s bodyguard and shadow, before he can ring the authorities, it takes ages and a kettle full of soup [thrown at head], a carving knife [which breaks when plunged into collar bone], a shovel [smashing shins], and an oven [most of him dragged into] before the poor guy is dead, the scene finishing with a harrowing overhead shot of Gromek’s hands, the rest of him inside the oven, struggling for life. Both Herrmann and the replacement composer John Addison wrote music for the scene, but it works fine without it.

It all eventually hinges on Michael having to get a professor to divulge a formula, though Hitchcock fails to make two people writing mathematical equations on a blackboard suspenseful, and then a lengthy escape section. There’s a very tense moment when Michael and Sarah are trapped in a theatre reminiscent of a scene in Saboteur, but a bus ride and pursuit is undone by the worst back projection used in a Hitchcock film since The Man Who Knew Too Much, though it’s not as bad as an earlier scene on a tractor where it doesn’t even seem to be moving half the time even though it seems like it’s supposed to be doing so, or Michael and Sarah’s reunion taking place on a fake plastic looking hill set which would have looked out of place even in an MGM musical from the ’50’s. 1966 audiences would probably have laughed at all this, but it’s not so much the artifice that’s wrong with much of this – Hitchcock’s films often contained this kind of thing – it’s that that it’s done so badly and with little artistry. Likewise the inconsistent aspects of the plot, like Michael and Sarah going out into an open space to avoid being overheard yet soon after somebody communicating confidential information to Michael in a hospital room, seemingly oblivious to the possibility of wiretaps, wouldn’t annoy so much if the film had been more entertaining, or more thrilling, or just….more. One odd moment has somebody recognising the dead Gromek’s picture in the paper and seeming really distraught. Actually, he’s supposed to be Gromek’s brother, but it’s hard to figure this out because his other scenes were all cut out.

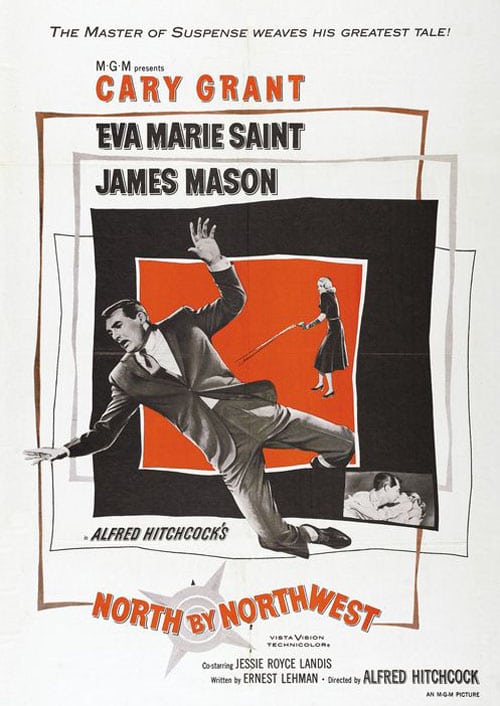

For the most part, the really good touches are short and sweet. The afore-mentioned reunion scene takes place mostly at a distance where we can’t hear the dialogue but don’t need to. Sarah begins to cry and a ripple effect dissolves to the next scene. A ballerina recognises the couple whilst performing and is freeze framed. A superb and very carefully put together single shot of the couple in a hotel room with their backs to each other, he shrouded in darkness while she’s by the window and slightly illuminated by outside light. Newman is really stiff and looks lost throughout, the only really poor performance I’ve seen him give, but this is compensated for by some fun supporting performers who provide the film’s only humour, like Wolfgang Kieling as the ill-fated guide Gromek who constantly chews gum and repeats American sayings, Ludwig Donath as the crotchety Professor Gustav Lindt [his reaction when he realises he’s been duped is priceless, and is enhanced by a nice aerial shot], and an eccentric appearance by Lila Kedrova as the flamboyantly dressed Countess Luchinska [oddly enough, Hitchcock decided not to try to make Andrews look glamorous] who helps Michael and Sarah in their escape attempt in return for their sponsoring her to go to America. Torn Curtain does contain things to enjoy, but watching it, I always think of how Hitchcock would have made a far better job of it back as an 80 minute picture in the 1930’s, with so many of its scenes cut to the bone. As it stands, it would really benefit from heavy cutting. It’s not at all like North By Northwest where, despite its considerable length, nearly every scene seems essential and the result flows really well.

John Addison’s replacement score often seems badly played and recorded, especially during the main title piece, which in no way gets one in the mood to watch a spy thriller. It has some good sinister moments, but is often too light for the picture or drones on and on in scenes where it isn’t needed. Its centrepiece is a pleasant love theme which was turned into a song by Jay Livingston and Ray Evans [the writers of Que Sera Sera] called Green Years, though bits of it appear at odd occasions. Herrmann’s score, which has been recorded twice, though very heavy and brooding, is definitely far better and would have enhanced Torn Curtain a bit. There is certainly enough in Torn Curtain to make it – just about – a worthwhile viewing experience, hence the reasonable star rating I’ve given it, but Hitchcock’s heart obviously wasn’t in it, something which is evident by his soulless, pedestrian handling, despite it revisiting a world in which he was interested it, and it really is badly flawed in some areas. Anyone watching it without having seen a Hitchcock film would probably wonder what the fuss is about. And things were about to get far worse before they could get [a little] better again. I really do believe that the Master Of Suspense lost much of his fire and touch after Marnie.

Be the first to comment