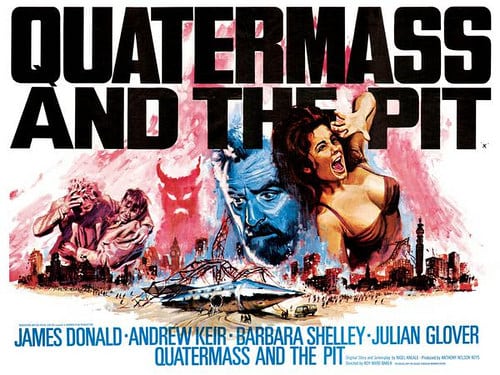

Quatermass and the Pit (1967)

Directed by: Roy Ward Baker

Written by: Nigel Kneale

Starring: Andrew Keir, Barbara Shelley, James Donald, Julian Glover

UK

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME: 97 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

The building of an extension to Hobbs End underground station in London reveals skeletal remains of a group of apemen over five million years old, more ancient than any previous finds, and part of a large metallic object believed to be a bomb. Meanwhile, Professor Bernard Quatermass is dismayed to learn that his plans for the colonisation of the Moon are to be taken over by the military led by Colonel Breen. Quatermass accompanies Breen to Hobb’s End where Breen thinks the object is a V-weapon. When another skeleton is found in an inner chamber, Quatermass suspects it is of alien origin, but palaeontologist Dr Matthew Roney is certain the ape men are terrestrial….

Though not many seemed to like the film, Mission To Mars did impress some with the audacious information concerning mankind’s ancestry revealed at the film’s conclusion, and it was left to know-it-alls like myself to say that it was actually partly copied from Quatermass And The Pit. There was also a Doctor Who serial called The Daemons which took some of the aspects from the Hammer film that Mission To Mars didn’t. Still, you could say that good ideas are worth rehashing some times, and writer Nigel Kneale himself was possibly influenced by Arthur C. Clarke’s novel Childhood’s End. In any case, despite being made far later than was initially intended, Quatermass And The Pit is the best of Hammer’s three Quatermass films and in my opinion belongs in the studio’s all time top ten films list, though it doesn’t seem to come up in best of Hammer lists very often, perhaps because it’s not really archetypal Hammer, being set in the present day and largely avoiding the Gothic. Despite being extremely talky, it’s quite frightening, often in a more subtle way than Hammer normally went for, and is absolutely loaded with intriguing ideas, Kneale hitting a creative peak with his fascinating mixing of anthropology, religion, the occult and extra-terrestrials. Whether it’s better than the 1958 serial version on which it’s based is hard to say. That benefitted from a slower pace which allowed the information overload to be more easily processed, and its moody black and white photography provided more atmosphere, though the film version is more lavish and exciting.

Kneale wrote his first movie condensing of the serial – which entirely removed one character, the journalist James Fullalove – in 1961, to be filmed in 1963 with Val Guest again directing and Brian Donlevy reprising the role of Quatermass. However, Hammer’s usual US distributor Columbia weren’t interested, even with the lowering of the budget and a revised script which substituted the weak throwing of a chain into the pit for something more cinematic, had a different final scene, and changed the main locale from a building site to an underground station. The film eventually went into production in 1966 as part of the distribution deal with Seven Arts, ABPC and Twentieth Century Fox, but Guest was busy on Casino Royale so veteran director Roy Ward Baker [A Night To Remember, The One That Got Away], who’d switched to TV for some time, was asked to direct, kicking off the second part of his movie career in which he mostly spent making horror films. Early posters featured John Neville as Quatermass, while André Morell, who’d played him in the TV serial, turned down the part. Andrew Keir was then asked and accepted, but he later said that the shoot was “sheer hell” because Baker wanted Kenneth More, though Baker denied that. Owing to lack of space the film was shot at Elstree’s MGM studios rather than Elstree’s Associated British Studios. Double billed with the average mystery Circus Of Fear, it was a hit in the UK, but the US release, re-titled Five Million Years To Earth, flopped. Still, Hammer quickly announced that Kneale was writing a new Quatermass story for them but the script never went further than a few preliminary discussions. He eventually wrote a four-part serial called Quatermass for ITV in 1979, an edited version of which was also given a limited cinema release, as well as the radio docudrama The Quatermass Memoirs where Keir reprised his role.

Portions of a skull appearing to form a complete one are seen beside the title of the film, and then we don’t get the rest of the credits until the end, an unusual choice for the time. A bobby on the beat then takes us into the underground station where much of the action will take place. After the finding of the skeletons, a reconstruction is made of what Dr Matthew Roney thinks the ‘ape men’ looked like, and the hunched Goblin-like model is quite an unsettling sight. Quatermass is introduced passionately arguing against Colonel Breen about the military taking over colonisation of the Moon, and straight away he’s a far more likeable figure than the Quatermass we’ve seen before – in fact he almost seems like a different character altogether – but then some years have passed since then. Quatermass and Breen continue butting heads as the investigating of the skeletons and the mysterious object reveals more and more strange facts which Breen just can’t accept. Quatermass becomes intrigued by the name of the area, recalling that “hob” is an old name for the Devil. There’s a creepy scene in a destroyed house with scratching on the walls where ‘ghosts’ have been seen – ghosts who, judging from their description, look like Roney’s Goblin. A soldier tells of how he saw one, and every true horror fan knows that seeing and hearing somebody describe something can often be scarier than us actually seeing the apparition in question because the mind can then conjure up the visuals. Working with Roney’s assistant Barbara Judd, Quatermass finds historical accounts of hauntings and other spectral appearances going back over many centuries in the area. And when they get into a sealed chamber in the craft, they’re greeted by the corpses of three-legged, locust-like creatures with horned heads – creatures which may have come from Mars and which look like many pictures of the Devil.

Even though much of the time is devoted to Quatermass rather too quickly working things out, the steady accumulation of increasingly outlandish reveals keeps the tension bubbling, tension that refuses to be undercut by a rather daft scene where Roney has conveniently built a machine that can tap into people’s psyche and which records the thoughts of Barbara while she seems to be possessed. The thoughts are transmitted onto a TV monitor and we see lots of the locust things hopping about in what is a ‘race memory’ of Martians on their home planet. The idea has potential and I was rather unsettled by the creatures when I saw the film as a kid, but needs more build-up and explanation when seen as an adult. Though there’s a terrible looking shot of part of the spaceship cracking early on, the scenes of stuff flying everywhere in the final third as Martian energy begins to threaten London look pretty convincing, and the image of the white locust-like Devil in the sky for me works for me because of its simplicity [though others disagree], and anyway the concept itself is just so frightening. While a more expensive picture would have allowed for a greater sense of Earth being in danger, the typically meagre Hammer budget still enabled Baker to stage some decent sequences of crowds of possessed people running amuck [even if cinematographer Arthur Grant has to mostly get in tight], and even a few buildings falling down. It’s just a shame that the Devil is rather quickly vanquished when somebody remembers that iron is dangerous to it, and – oh look, there just happens to be a crane over there! – though one of the characters does amusingly remark “it’s too simple”, and the scene is really quite well put together with minimal use of back projection. If only they’d staged all this in proper nocturnal darkness instead of the usual day-for-night stuff which doesn’t look like either one or the other.

The basic premise is nothing less than fascinating, though contains quite a lot to process. Millions of years ago, the Martians fled their dying planet and, unable to survive on Earth, chose to preserve some part of their race by creating a colony by proxy by significantly enhancing the intelligence of the natives. Their descendants evolved into modern humans but retained the vestiges of the Martian influence – which they interpreted as the Devil – buried in their subconscious, and people who have psychic abilities and who can see ghosts have more of the influence than others. Phew! Though still in many ways a horror, there’s very little blood in this one – in fact the usual shock tactics are generally ignored. There’s not even any sexualisation of a female character –the sole main woman in the film may be played by Barbara Shelley but she’s just there to do her job and not just look pretty even though, being Shelley, she can’t help but look pretty anyway. Grant gives the film a rather lush, colourful look which sometimes shows up the fakery of the sets [though look out for the movie posters, including some Hammers, on the station walls] , while Baker’s ‘matter of fact’ approach may miss the odd chance for thrills but ends up having more quietly effective results.

Kier is so much better than Brian Donlevy from the first two Quatermass pictures [for a start, he was probably sober] that it’s hard to understand why he wasn’t cast in the part back in 1954, but he now brings a world-weariness, brought on by much disillusionment, to the character. After Father Sandor in Dracula: Prince Of Darkness, it’s my favourite of Keir’s Hammer roles. Julian Glover tries to make something more of the typical uptight military person role he’s given. Musically Quatermass And The Pit is a bit of a disappointment. Tristram Cary’s electronic cues, which really double as sound effects, are eerie, but little of his orchestral score remains in the film. Extensive re-cutting meant that many of his cues had to be replaced by library tracks, which are generally okay but tend to overdo the “dun dun DUN” thing when a scene ends with a revelation. A surprising number of scenes employ minimal or no music at all. In the late 90’s, it was announced that Alex Proyas was to do a remake [though it failed to materialise], and I suppose that this story may possibly benefit from a remake with all the technological advancement we now have [though I always prefer practical effects mixed with CGI if need be rather than all CGI], and of greater length. But Hammer’s intelligent, rather neglected minor science fiction/horror classic has enough merits to not make a remake really necessary. I still personally find it rather chilling, partly I suppose because it really makes you think – and we all know how thinking can bring up the most terrifying thoughts.

Be the first to comment