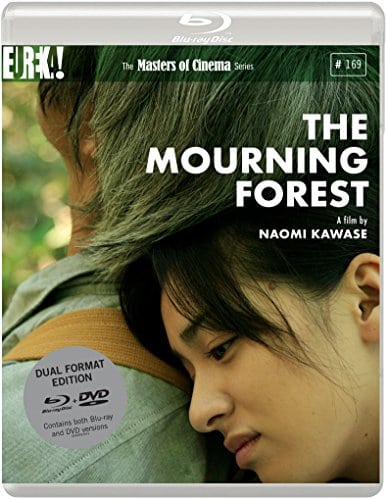

The Mourning Forest (2007)

Directed by: Naomi Kawase

Written by: Naomi Kawase

Starring: Kanako Masuda, Machiko Ono, Shigeki Uda, Yôichirô Saitô

AKA MOGARI NO MORI

AVAILABLE ON DUAL FORMAT BLU-RAY AND DVD: Now, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 98 minutes

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Machiko is a young nurse, still coming to terms with the grief she feels for her young son who has died in an accident. She takes a job at a care home for the elderly where she makes the acquaintance of a widower, Shigeki, who suffers from dementia and who seems to be in constant mourning for his wife who died 33 years ago. Machiko warms to Shigeki and takes him out for a drive but when the car breaks down, he wanders into the nearby forest, leaving her little choice but to follow him. Shigeki seems to be pursuing some mysterious resolution to his grief….

Sometimes it’s good to watch something that you’ve never heard of and which wouldn’t normally be on your radar. I’m afraid that my experience of the more ‘arty’ side of Japanese cinema pretty much stops with Akira Kurosawa, so I had little idea of what to expect with The Mourning Forest, which won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2007, nor can I really place it in context, though I did detect certain similarities with the work of Terence Malick and Andrei Tarkovsky. A very minimalist meditation on grief and loss, it doesn’t really attempt to offer much insight into its subject, but then I find that some films that try to do so don’t get quite right, often sugar coating and over-sentimentalising something that is an unquantifiable emotion which no words or actions can wash away, and which everyone who suffers will feel in a different way. Naomi Kawase’s film seems to me in some ways a more honest picture than some dealing with this depressing subject- albeit a subject which will affect all of us at some point. Perhaps this is partly because it’s steeped in a culture that’s very different from ours, especially concerning the subject of death which in Japan has many rituals connected with it, this slightly distancing effect meaning that we’re not spoon fed emotions, nor are we seeing things which contradict our own experiences and feelings on the matter.

One thing I should warn the reader right now is that The Mourning Forest moves at an almost glacial pace, the camera often choosing to linger for ages on the trees and the fields which most of it takes place in. Add to this the fact that large stretches of the film contain no dialogue, and I suppose we have a film that a few may find it boring. I can’t say I found it boring myself. Similar in a way to the currently-in-cinemas A Ghost Story [with which it shares similarities in subject matter too], this is one of those films where you’re invited to look upon something and to just think, to just immerse, and to bring your own feelings to the table. Slow can be just as enjoyable as fast. While I was satisfactorily entertained by Guardians Of The Galaxy Vol. 2 for most of the time, I found its last half hour [where endless CGI was being thrown at me] so boring that it almost put me to sleep. In a way, you could say that hardly anything happens in The Mourning Forest. But you could also say that, actually, a hell of a lot happens if you consider what’s going on inside the character’s heads, and the importance and universality of their emotions and their decisions.

The film actually opens with two of these extremely long shots so it’s not as if it doesn’t warn you what it’s going to be like, though we’re then suddenly interrupted by an axe cutting into a tree. We’re in the countryside surrouding a nursing home, and it seems to be a much more pleasant, relaxing place then the nursing homes we tend to have here in the UK, but this shouldn’t be a surprise if you know how the Japanese refere their elders, in marked contrast to here. Something that also occured to me, unless I was reading too much into what I was seeing, was that this place seems to be almost midway between the ‘civilised’ and the ‘natural’ world, the latter being the place from which we came and maybe to where we return – and therefore a bridge between life and death, populated by people who are soon to cross over. The film seems to be full of this kind of symbolism, yet it doesn’t tend to scream at you – in fact more casual watchers may not pick up on much of it unlike me who was doing his utmost to concentrate and try to notice as much as he possibly could! Anyway, we soon meet Machiko, starting her first day at her new job and joining the other staff members in taking the residents out for a walk. She’s grieving for her dead son, something emphasised in a quietly powerful flashback later on as her husband cries: “Why did you let go of our son”?, the camera focusing solely on Machiko. Shigeki is introduced asking a visiting monk “Am I alive?”, to which the monk offers a lengthy explanation that ends with him asking Machiko to place her hand on Shigeki’s and ask a polite question so he can respond. The idea is that as long as Shigeki feels Machiko’s presence and can respond to her, he can feel the sensation of being alive.

Shigeki lost his wife Mako 33 years ago, and is still grieving deeply, plus he’s suffering from dementia. There are a few quite upsetting moments, like when Shigeki thinks that Machiko is Mako, or when he flies into a rage and actually injures Machiko when she intrudes on his privacy, or a dream scene which really will make you cry when he remembers accompanying Mako on the piano, only to gradually forget what notes to play as she gets up and walks away, his memory fading. However, once outside, Shigeki is a different person: playful, impetuous, even unruly. He runs around pretending to hide, then, when Mako takes him out for a drive, wanders off when the car hits a rock and her back is turned. Now she has to find and then try to keep up with him. A man most definitely on a mission, he seems to now be composed of great endurance too. What’s he looking for? Could it be something to do with the fact only when someone’s been dead for 33 years do they actually cross over into the afterlife? Or maybe what’s in his bag? Over half of the film consists of the two trudging through the forest and there were a couple of moments when even I got slightly restless but as I stated above, I can’t say I was actually bored. The relationship between Machiko and Shigeki, based primarily on mutual need but also one that becomess increasingly educational to both parties, is warm without becoming mawkish or uneasy despite a moment where she strips off so they can keep each other warm. They do share dialogue scenes, but they seem to be deliberately awkward, looks and gestures carrying more weight. And the conclusion where everything fits into place is certainly one that’s logical.

So why, despite all this good stuff in a film that I found rather meaningful, do I now find myself having to be negative about one aspect which may only be one but which did hold things back for me a bit and became rather distracting and even annoying. I’m talking about of course my old bugbear generally known these days as ‘shakycam’ which is hardly used at first in this film, the mostly handheld cinematography not being bad at all, but which is seen more and more as the film progresses and ended up preventing me from being moved much by the final scenes. I just didn’t feel able to really get caught up in the otherwise beautifully handled moments here because I was more getting irritated by the camera being unable to stay still for one bloody second. Of course there are many films where the ‘shakycam’ is far worse and Kawase, who began her career making documentaries, obviously had her reasons for having Hideyo Nakano shoot her picture in this manner, but the device just seems at odds with the wistful, tranquil,mysterious film that she’s made.

Still, I have no complaints whatsoever about the acting. Shigeki Usa makes the confusion, pain and determination of Shigeki seem touchingly real, and Machiko Ono, who doesn’t seem to have any other screen credits so may very well not really be an actress at all [it seems that Kawase often likes to use amateur performers who can sometimes bring a realism that seasoned professsionals cannot], totally sells her character’s journey. There’s one moment where she bursts into histrionics which could almost have seemed out of place in such a contemplative film but for her totally convincing evoking of Machiko’s emotions which have now finally boiled over. There are some minor characters in the first 40 or so minutes, the most prominent being a fellow nurse who also teaches Machiko something and helps to point her in the right direction, but this film is a two-hander for much of the time. Undeniably sad – how could it not be considering what it deals with, but restrained, ever so slightly mystical, and not – I don’t think – morbid – The Mourning Forest is far more intriguing than its synopsis may lead you to believe, and will probably keep you thinking – and not necessarily in a sad way, as its ending becomes oddly uplifting the more you think about it. I’m now going to admit something right here because I feel it’s pertinent. I’m suffering from grief myself, and have been for over a year, and while some things near the beginning were a bit hard to take in no way do I regret watching this film. So say to any readers in a similar boat who think that this might be a film to avoid, I think that you may be surprised and it may even do some good. As I come to the end of this review, the main thing bothering me is still the filming style which still seems to me a baffling choice.

The Mourning Forest looks stunning on Eureka Entertainment’s Blu-ray. The only slight nitpick I have is that some of the background dialogue isn’t subtitled, though that’s probably not Eureka’s fault at all.

SPECIAL FEATURES:

*Stunning 1080p presentation on the Blu-ray, with a progressive encode on the DVD

*Choice of 5.1 DTS-HD or uncompressed PCM audio on the Blu-ray

*High-definition stills gallery

*PLUS: A booklet featuring a statement from Kawase made at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival, alongside stills from the films production

Be the first to comment