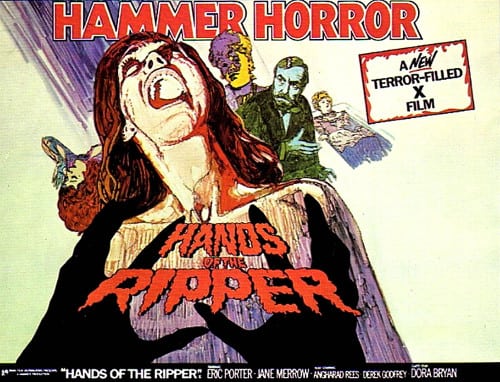

Hands of the Ripper (1971)

Directed by: Peter Sasdy

Written by: Edward Spencer Shew, L.W. Davidson

Starring: Angharad Rees, Eric Porter, Jane Merrow, Keith Bell

UK

AVILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME: 85 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Jack the Ripper murders his wife while their young daughter Anna watches from her cot. Anna is subsequently brought up by fake medium Mrs Golding who uses her to help her make money from a gullible public. When she forces her into prostitution, her first client gives her a brooch which, when it catches the light, causes Anna to kill Mrs Golding. John Pritchard, a doctor intrigued by the new technique of psycho analysis, takes Anna into his care – something he may soon regret….

Hammer went through a rather interesting phase in the early 1970’s, a period where they were considered to be in decline [well I guess in terms of box office receipts that’s true] but in which they did make some attempts to breath new life into their Gothic template. The first of two Jack the Ripper-themed pictures the studio made in 1971, Hands Of The Ripper partly combines a variant of Marnie with a proto-slasher flick and comes out as a surprisingly intelligent, even ambiguous endeavour that makes a considerable effort to avoid that Hammer camp which us fans love but which many choose to use to mock the studio’s horror movies. It has two excellent central performances and, while I mentioned in my review for Countess Dracula that that film had a lush look to it missing from the other later Hammer’s, this one actually looks just as fine and has some Victorian set dressing which is among Hammer’s most authentic – though saying that one has to chuckle at the mention of a clearly alive Queen Victoria despite the film being set fifteen years after the Ripper murders, making it 1903, two years after she died. The only prominent flaw is one that many of the more ambitious Hammers have – the running time is too short to properly accomodate and develop its themes.

Hammer actually first made a Ripper-themed film in 1950 called Room To Let, though I was unable to view or obtain it. It was another variant on The Lodger, best filmed in 1926 by Alfred Hitchcock. Hands Of The Ripper begun life as a story outline by crime writer Edward Spencer Shew which turned up in the office of an executive at Rank, Hammer’s main distributor of the time. This was turned into a screenplay by obscure Canadian screenwriter L.W. Davidson, while Shew turned his tail into a novel to tie-in with the film’s release, though it differed substantially from it, being set in 1888 the year of the Ripper murders and imagining the Ripper as a woman possessed by the spirit of an earlier serial killer. The film was shot at Pinewood, making use of the large Baker Street set left over from The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes, plus a few London locations like Paddington Station. They were refused permission to shoot in St. Paul’s Cathedral, so they created the Whispering Gallery through a combination of photographs and a studio set. It’s noticeable in high definition if you look closely, though it certainly wasn’t before. The BBFC requested the removal of a shot of hat-pins in a woman’s eye, though it was later restored. In the US, 16 seconds of footage from two of the murders was cut. Rumour persists that a more graphic version of Dolly’s death was filmed for the Far Eastern market and turned up on a 16mm print, though it hasn’t been located so far. The double bill with Twins Of Evil was reasonably successful and Hands Of The Ripper was better reviewed than was the norm for Hammer. In 1972, A US TV version cut more violence and added footage of a colleague of Dr. Pritchard, though that now also appears to be lost.

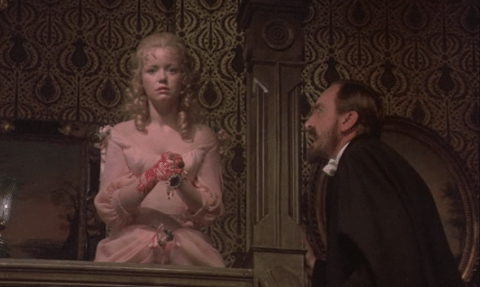

“It’s the Ripper” are the first words heard as we open with the discovery of a dead body in time-honoured Ripper movie style, though the scene that follows is surprisingly intense. The Ripper returns home and his wife sees the blood on his hands, whereupon he stabs her to death while their very young daughter Anna watches. It’s worth noting now that this film makes no attempt to identify the Ripper, who has syphilitic patches on his face – even when a medium later on says that she can’t say who the Ripper is, even though she obviously knows! Apparently nobody has been able to identify the actor who played the Ripper either – in fact none of the performers in this scene are credited – but he certainly has a scary presence. The titles unfold over freeze-framed shots of this opening sequence which is cut back to several times later. We then cut to a seance, the camera doing a neat 360% pan revealing all the people there. John Pritchard and his son Michael know that it’s a fake and John reveals a grown Anna standing behind some curtains, so Mrs Golding attempts to pass her off as a whore, with disastrous results. We don’t see Mrs Golding’s death – rather, the camera shows her in some kind of pain, then she gasps, after which she’s then revealed to have been pinned to a door with a poker. Super strong this girl is when she goes into one of her trances. John sees politician Dysart fleeing the scene of the crime, but doesn’t let on to the police that he saw him because he wants him to find out about Anna’s background. He rescues Anna from the local police jail and takes her back to his house, so he can cure her of what he sees as schizophrenia.

Every now and again you know that Anna will see some flickering light and will go into a trance, and soon after that you know that she will probably be kissed, and that she will respond in a particularly violent fashion using whatever potential weapon is at hand. The neck slashing of Dolly is perhaps the goriest murder, though the hatpins in the eye perhaps the most memorable. The victim’s hand covers the eye which the pins go into, but we then see her stagger about the street and finally a close-up of her convincingly gored eye. The kills may be brief by modern horror standards but are still effective and Angharard Rees [more on her quite superb and sadly neglected performance later], despite her delicate build and features, is somehow able to convince us that she has great strength when she goes into one of her trances. I could have done with a bit more ramping up of the pace in the film’s finale act, but the climax may very well be one of Hammer’s best, surprisingly quiet and subtle as Anna and Michael’s blind fiancee Laura go up to the Whispering Gallery in St. Paul’s Cathedral and they whisper to each other, only for a third male voice starting to be heard, the voice of Anna’s father – until a dying John staggers i to the cathedral and tries to get Anna to jump and join him. The last few seconds are quite similar to that of The Gorgon and similarly full of tragedy. Even the hymn the choir are singing in the background has a strong melancholic feel.

As with director Peter Sasdy’s earlier Taste The Blood Of Dracula, the story is partly about the breakdown of a hypocritical Victorian society and family, and the sins of parents being visited upon their offspring, though this one also looks at psychoanalysis and seems to find it wanting. John, though the supposed ‘hero’ of the piece, can also be considered as the true villain of the movie. He’s so convinced that Anna’s condition is something which can be cured that he’s willing to break the law, from harbouring a murderer to indirectly causing the deaths of three people. Even when a visit to a [real] medium reveals the truth about her past, he refuses to believe it and reckons that her illness was just caused by the flickering of fire into where she used to be hidden when she pretended to be ghosts for Mrs. Golding. He only realises the truth when it’s too late. And are his intentions strictly honourable or is he just on a big ego trip, and does he also perhaps have romantic feelings for her and want a replacement for his dead wife? Eric Porter doesn’t really let on in his very clever performance, and the film doesn’t really answer even the last question until the end when it might be a combination of all these things. Nor does it really tell us whether Anna’s actually possessed or not, apart from syphilitic boils appearing on her hands when she kills, a device which is overly obvious and which the film could have done without. Questions questions, and I recall being frustrated at these when I first saw the film as a teenager, but now I think it’s nice that a Hammer film dares to be this way. There’s also a surprising amount of soft focus photography courtesy of Kenneth Talbot, creating quite a visually pleasing piece despite the prevalent browns [rarely the most aesthetically pleasing colour], while Sasdy’s direction is less stylised than before except for some effective use of Dutch angles, but totally in control of the material.

Keith Bell and Jane Merrow, the latter very good indeed as a blind lady, are more interesting than the usual Hammer romantic leads, while Rees is wonderfully delicate and innocent – well except for when she ‘loses it’ – and makes you totally sympathise with Anna and her situation despite her propensity for murder. It’s one of the best female performances in a Hammer film and should get a great deal more attention that it does. Both leading ladies are different from the typical model type. Anna is continually accompanied by a beautiful, Erik Satie-like musical theme from composer Christopher Gunning that truly evokes her innocence and the tragedy of her existence. The score doesn’t consist of much else, but that theme may stick in your head for some time. There’s a surprising sensitivity about Hands Of The Ripper despite it also being a film where someone has to die a bloody death every twenty minutes. While still undoubtedly taking advantage of the relaxing of censorship, Hammer certainly made a good stab [sorry] at making a quality movie here, and the result has dated less than much of their other stuff too. Not quite one of their all-time classics, but well worth checking out if you think their horror film are all pretty much the same.

Be the first to comment