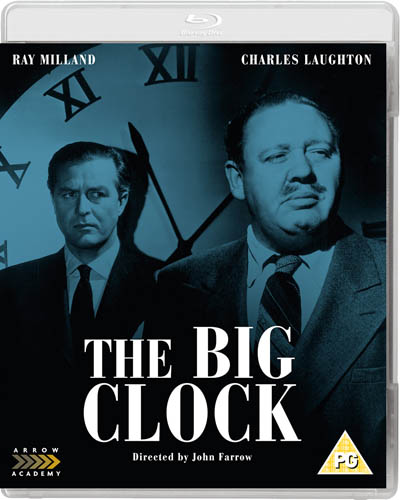

The Big Clock (1948)

Directed by: John Farrow

Written by: Harold Goldman, Jonathan Latimer, Kenneth Fearing

Starring: Charles Laughton, George Macready, Maureen O'Sullivan, Ray Milland

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: NOW, from ARROW ACADEMY

RUNNING TIME: 96 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

George Stroud, editor-in-chief of Crimeways magazine, has his holiday postponed yet agin eager by his boss, Earl Janoth, who fires Stroud when he refuses to stay. Stroud goes to a bar to drow his sorrows and ends up spending a drunken night out with Janoth’s mistress Pauline York. Janoth sees a man leave her apartment and kills her in an argument. Rather than go to the police, Janoth decides it’s better to frame the man he saw leaving York’s apartment for the crime, and use the resources of Crimeways to find his identity….

The Big Clock is probably less known than its 1987 remake No Way Out, which changed a great deal but is actually more noir-ish than its predecessor, something that’s unusual. The Big Clock is noir all right, but it lacks the usual playing with black and shadows, and also brings in elements of comedy, especially screwball, with lots of snappy repartee, eccentric characters and a general feeling that it’s all a bit of a laugh. The most amazing thing is that, for the most part, it works. From about a third of the way through, it becomes really quite strange, an ironically amusing yet still suspenseful twist on the idea of people trying to identify and catch a murderer, the main character caught in a darkly comic nightmare as he has to be part of an investigation to catch – himself – while the film, rather than opening out in the Hitchcock fashion so our hero can be chased through interesting locations, becomes increasingly confined to the building in which George Stroud works, eventually being completely unable to leave. I don’t think it’s quite an all-time classic – for example the story line sometimes needs its hero to behave strangely so it can be carried forward, the humour tends to be more slightly amusing rather than really funny, and repeated motifs such as clocks and the colour green work more as fun gimmicks than actual ideas that relate to what’s going on. But there’s still plenty of entertainment to be had in what could have been something of a disaster considering that its two principal genres are about as far from being bedfellows as can be.

It was based on a novel of the same title by Kenneth Fearing. He partly wrote it as revenge on publisher Henry Luce and his Time magazine, with Earl Janoth intended as a parody of Luce. Fearing had to work for Luce many years for financial reasons but hated the experience. Paramount actually bought the rights to the novel before it was even published because Fearing’s earlier novel The Hospital had been a best seller. Screenwriter Jonathan Latimer made some major alterations, most notably the Big Clock itself, which in the novel is referenced as only a metaphor for the inevitability of the uncaring passage of time. Leslie Fenton was announced as director but he was held up on Saigon so John Farrow took over. This was Maureen O’ Sullivan’s [Jane in the Tarzan films] first film in five years, doing it as a favor for her husband Farrow, though she still had to audition. Charles Laughton’s salary included the fee for his wife Elsa Lanchester who had a small role in the film. Tension on set was cause by Ray Milland hating Laughton because of his homosexuality. When producer Richard Maibaum first came on the set, Farrow, who liked to intimidate people who worked with him, kept him at a distance by using a walking stick. Maibaum turned around, went to the props department and returned with a baseball bat. As if a spell were broken, the situation immediately improved and Maibaum and Farrow would go on to have an excellent working relationship. Reviews and box office were good if not quite excellent.

The film’s opening is striking, though to be honest it sets a very dark, fatalistic mood which doesn’t really return. The camera pans along some New York skyscrapers, the background sky becomes black to disguise the dissolve to a single building, zoom into one of its windows and into a really disorientating maze-like set of a room that’s also the inside of a huge clock, the latter being a really well accomplished piece of special effects. Stroud’s nervous narration and his asking “how did it all start”? causes us to flash back to when Stroud is one of Janoth’s most useful workers, expert at identifying leads through what he calls “the system of the irrelevant clue”, in which he picks up on and continues minor strands that the police are too busy to pay attention to. Unfortunately, it’s ironically largely because of Stroud’s expertise that Janoth is so cruel to him, unwilling to let him go on his honeymoon because he just can’t do without him, and poor Stroud has now been married for seven years and even has a five year old, while his wife Georgette is understandably getting fed-up. Janoth rules his workforce with an iron rod, personally micromanaging everything right down to the light bulbs in a broom closet – for which a janitor loses his job when one has been flickering for a few days. Board meetings tend to consist of subordinates having to come up with ways to make readership grow even more and, of course, make Janoth richer, while employees aren’t even allowed to have proper lives outside the job. The film’s idea of a corporation trying to control everything is rather forward thinking. While Janoth has a mistress called Pauline and therefore probably a wife also, his real fetish seems to be for punctuality, which is why he’s installed this clock in the lobby of his skyscraper in New York, a clock which runs on naval observatory time and in tandem with all the clocks in all the buildings that Janoth Publications has. Laughton again brilliantly plays an unpleasant character whom you don’t like but can’t help but have some sympathy for.

Stroud goes to a bar and is found by Pauline who has her own reasons for disliking Janoth and wants to blackmail him using some information she has. Georgette finds them and isn’t too happy but never mind, the couple are soon going to go on their long-awaited vacation. But the next day Stroud is fired, Janoth obviously having no idea that Stroud wouldn’t give in to him. He rings Georgette to tell her, leading to the exchange: “We’re unemployed and broke”. “It’s too good to be true”. “Blacklisted for life, never to work on a magazine again”. “Oh George, how wonderful”. But when Stroud returns to the bar, he drinks so long with Pauline that he misses his flight. Whoops! It’s hard to believe that this supposedly dutiful married man about to [finally] go on his honeymoon would go on a booze binge with this woman without mentioning the point of their first meeting – and it’s odd that between bars he buys a painting and a sundial – but it’s kind of amusing seeing Ray Milland do this as he hadn’t long starred in The Lost Weekend. I don’t think it’s being inferred that the two have sex, but Stroud is soon in a fine mess anyhow [during the quarrel you get a great close-up of Laughton’s face so you can see his quivering lip], even if that’s not enough to explain his seeming lack of concern over Pauline’s murder. He does act strangely, this guy. Anyway, Janoth gets him to lead the effort to find the mystery man whom he wants to frame, even though he mentions enough details for Stroud to know that the mystery man is actually himself! The evidence actually points to one of Stroud’s bar acquaintances. Milland, who could be rather stiff, really makes the viewer feel his plight as the noose tightens, and it’s almost brilliant the way you feel like laughing at the farce while still being on the edge of your seat as you watch Stroud trying to lead this investigation yet also sometimes misdirect it while he looks for evidence of the real culprit. You do eventually get some moody sneaking around in dark rooms and a great death, plus a clever if perhaps too neat unmasking.

007 fans will notice Stroud’s method of imobolising electronic doors, and, considering that the film’s producer is Richard Maibaum who wrote most of the early Bonds, may smile that he has to get about in a building full of minions ordered to shoot to kill lead by a power-mad villain. Janoth has a main henchman, Steve Hagen played by perennial bad buy George Macready, who is seemingly willing to obey his every command. Some typically ’40s [so incredibly subtle] suggestions of homosexuality seems to be present here, and I wondered even more about an odd scene where another of Janoth’s henchmen [M.A.S.H’s Harry Morgan!] massages his back and seems to get really angry even though he says or does nothing, while Janoth muses on his evil plan. The oddest character is Louise Patterson, another fine exercise in eccentricity from Elsa Lancaster in another weird hair-do. She’s plays a batty painter living in a house full of kids from her four husbands, the last of whom seems to be missing. She’s important to the plot because Stroud buys one of her paintings, but also provides the film’s funniest moments when hired [and hired is the word, she won’t do anything for free] by the police to sketch him. The revelation of the sketch and the film’s final moment which gives her latest husband the last lines are big chuckles. Elsewhere though, actual jokes are rather thin – you’ll smile rather more laugh – and this noir lover could personally have done with a little less joviality and more moodiness just to give things even more of an edge, but that’s just my personal taste, and one does have to admire the way that things are never allowed to slide into full-on parody.

Director John Farrow is not a very familiar name despite his many credits, which include two more fully fledged noirs, Where Danger Lives and Night Has A Thousand Eyes. He does a good job balancing what is sometimes disparate material, and employs a lot of complex long takes that sure must have taxed the performers as well as being a nightmare to set up. Look out for some very artistic dissolves too. Victor Young’s score surprisingly ignores the lighter shades of the film and goes for the darkness, with some very effective use of lower register instruments all providing a single, evil-sounding chord, in the final act. As to whether it’s superior or inferior to No Way Out is hard to say. Perhaps I personally still prefer the latter because it’s heavier on the noir feeling [even the ending isn’t exactly sunny] and the characters seem to be less callous, but it’s not really as clever and the plotting not as tight. Both remain good examples of two very different ways to tell the same basic story.

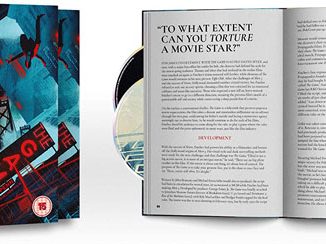

Arrow’s Region ‘A’/’B’ release of The Big Clock perhaps scores slightly better on special features than appearance. It looks like a first generation source was not available, as there is some visible print damage, flicker and uneven grain management. On the other hand though, the level of detail is very impressive indeed, and things certainly never look terrible. Compared to the DVD, I’m sure it looks brilliant.

One of my favourite commentators Adrian Martin provides the audio commentary. He’s typically observant and picks up on things lesser critics like myself don’t tend to pick up on, like linking things in the film to social/’political concerns of the time – while never getting too dry. He compares the film with the book [which was more obvious about the sexuality of some characters], make a good case for the seemingly under-regarded Farrow, and makes another good case for the film being a near-masterpiece. I also like the way he quotes other sources to strengthen his arguments rather than just taking time out every now and again. Very good. Turning Back the Clock has Adrian Wootton look at the film, often covering the same ground as Martin, but giving us a bit more on background, as well as telling us that itwas virtually a forgotten film for a long time. Simon Callow, who wrote a book about him, turns up in A Difficult Actor to look at and praise Laughton’s unique but often quite brilliant acting. Always great to listen to, he enthusiastically gives us an outline of Laughton’s career, places The Big Clock as one of the best offerings during a phase where Laughton tended to take roles for the money, and paints a picture of Laughton the person. A lovely inclusion. And then we have an hour-long radio adaptation with Milland and O’ Sullivan reprising his role. It mostly follows the film script to the letter, though of course minimising the action.

Good special features garnishing a rather different kind of film noir – Highly Recommended.

SPECIAL EDITION CONTENTS

*High Definition Blu-ray (1080p) presentation transferred from original film elements

*Uncompressed Mono 1.0 PCM audio soundtrack

*Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

*New audio commentary by film scholar Adrian Martin

*Turning Back the Clock, a newly filmed analysis of the film by the critic and chief executive of Film London, Adrian Wootton [23 mins]

*A Difficult Actor, a newly filmed appreciation of Charles Laughton and his performance in The Big Clock by the actor, writer, and theatre director Simon Callow [17 mins]

*Rare hour-long 1948 radio dramatization of The Big Clock by the Lux Radio Theatre, starring Ray Milland [59 mins]

*Original theatrical trailer

*Gallery of original stills and promotional materials

*Reversible sleeve featuring two original artwork options

FIRST PRESSING ONLY: Illustrated collector’s booklet featuring new writing on the film by Christina Newland

Be the first to comment