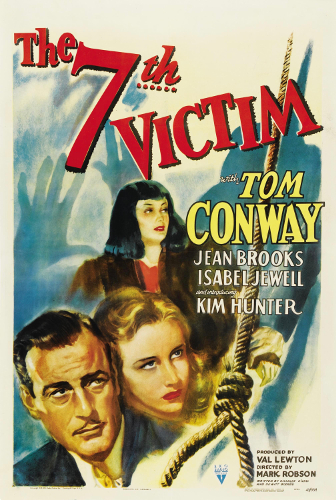

The Seventh Victim (1943)

Directed by: Mark Robson

Written by: Charles O'Neal, DeWitt Bodeen

Starring: Isabel Jewell, Jean Brooks, Kim Hunter, Tom Conway

USA

AVAILABLE ON DVD

RUNNING TIME: 71 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

SPOILERS IN LAST PARAGRAPH!

Mary Gibson learns that her older sister and only relative, Jacqueline Gibson, has gone missing and hasn’t paid Mary’s tuition in months. She decides to leave the school where she works to find Jacqueline who owns La Sagesse, a cosmetics company in Greenwich Village, New York City. Once there, she discovers that she sold the company. Soon after, Irving August, a private investigator helping her out, is murdered, Mary continues to elude her, and what’s all this about a Satanic cult called the Palladists?….

The Seventh Victim is sort of a difficult film to totally get a grip on. It’s probably the most personal of the Lewton horror films, and the most explicit statement of the depressed, morbid world view presented by them, at least out of the first four; I haven’t seen any of the later entries in the series yet. It’s stated right away in the opening bit of poetry from John Dunn, “I run to death, and death meets me as fast, and all my pleasures are like yesterday”, and the whole film is pervaded with it, finishing with a conclusion which is astounding for the time in its downbeat nature. Therefore it’s easy to see why many consider this to be the high water mark of the series. It has some truly chilling moments and images, and intriguingly seems to present a lesbian relation surprisingly overtly; I’ll present my theory as to why the censors allowed it later on. However, this movie is infuriatingly vague; yes, there was the Production Code to skirt around, but some things could have certainly been addressed more clearly, and it gets odd how characters refuse to address important details, usually while speaking in soft voices too. There are also several major inconsistencies which I find hard to believe that Lewton didn’t care about. Of course you could still say that all the questions left unanswered by the time the end title comes up just add to the disorientating effect, and, while I wasn’t totally satisfied by the film [though I liked it immeasurably more than after my first viewing a few decades ago], I do feel like I want to delve back into it and try to unravel some of its many mysteries.

The Leopard Man hadn’t been the smash that Lewton’s previous two had been but still did well, so it was on with the fourth film, with RKO execs handing Lewton just a title as usual. DeWitt Bodeen’s original script was about an orphan having to solve her identity while a serial killer was on the loose amid California’s Signal Hill oil wells. Lewton got Charles O’ Neil to write a new treatment, then asked Bodeen back to collaborate with O’ Neil on the screenplay. Bodeen actually got himself invited to a meeting of Satanists as research. The character of Mimi came from the opera ‘La Bohème’ by Giacomo Puccini. This was another entirely studio bound production, including again some usage of sets from The Magnificent Ambersons at the beginning, though initially Lewton and RKO had high hopes for this one, and agreed that it would be an ‘A’ picture with a higher budget than before. Mark Robson had edited the first three Lewtons and was now promoted to director; however, the studio heads didn’t want Robson and gave Lewton a choice: get rid of Robson or lose the A-picture budget. Lewton chose Robson. However, this meant that the film’s running time had to be shortened to around 70 minutes, so Lewton and editor John Lockert removed four scenes, and one wonders if they intended to create even more narrative confusion than already existed considering two of the scenes that they chose. Cut was Judd twice visiting satanist Natalie Cortez which reveals some information to the Palladists we otherwise don’t know how they got, Ward visiting Mary which explains a reference to a second visitor, and a coda concluding with some more poetry. Lewton planned to slightly extend the ending so it was smoother but didn’t have the money to do so. The Seventh Victim was the first commercial disappointment of this series, which isn’t surprising really, though its reputation eventually began to grow.

The first shot lingers on some stain glass windows, something that suggests religion will play a major part in this story, but it doesn’t until right near the end. Mary soon sets off to find her sister, and almost immediately the story becomes very similar in one respect to I Walked With A Zombie; the idea of an often absent woman who was a catalyst for most of the events that we see. It’s over half way before Jacqueline makes an appearance, but as Mary follows her from place to place, always missing her, we can often virtually feel her presence. It’s only partly stated of course, but Jacqueline appears to be somebody forever seeking new thrills, yet with a life that’s really rather empty. And it seems that one of these ‘thrills’ was Frances Fallon. Lines such as, “we were infamous” don’t necessarily mean that Jacqueline and Frances were involved and that Frances is in love with her even if this love isn’t returned, but it seems to be slyly hinted at, especially with Frances’s behaviour during the climax. But then most of the main characters are in love with somebody. Another friend of Jacqueline’s, Gregory Ward, is not just a lawyer but is Jacqueline’s secret husband. However, he and Mary start to fall for each other. Then there’s Jason Hoag, a poet who was once in love with a female patient of psychiatrist Louis Judd who mysteriously disappeared, and now he loves Mary. Oh yes, Louis Judd. Played again by Tom Conway, he may indeed be the person of the same name from Cat People, and even possibly refers to that film’s cat person in one line, but wasn’t he killed near the end of that film? Very strange indeed.

The shooting style here is quite naturalistic for a while, and I was soon wishing for some creepy atmosphere, but suddenly things change, with Robson almost precisely imitating the style which Jacques Tourneur had perfected in the previous three films. Mary and Irving August, a PI helping her for free because he’s intrigued by the case even though a mysterious man tries to warn him off, enter an apartment building which Jacqueline has been traced to. Jacqueline’s place is at the end of a corridor which is swallowed by black. The two stare into this dark abyss, neither wanting to go, both hesitating, aware that they are about to enter a different world. Eventually Irving goes forth and staggers back out with a knife in his stomach. She flees to the relative safety of the underground, and spends ages sitting on the same train until two men board dragging a drunk board and the drunk’s head rolls back to reveal it’s the dead Irving in a really unsettling moment. Of course when she returns to the carriage with the conductor they’ve all gone. Mary soon discovers that Jacqueline had been Judd’s patient, seeking treatment for depression stemming from her membership in a Satanic cult called the Palladists, who include Natalie Cortez the new owner of La Sagesse, and that Jacqueline murdered Irving, an issue never properly answered – just like some others. These Palladists are strange; they’re avowed pacifists, yet are still prepared to kill when necessary. They seem fairly ordinary, which somehow makes them more sinister even if it looks like they prefer to hold tea parties more than anything else, and not confirming whether or not they actually have any mystic powers is one of the more tantalising of the many questions posed. Saying all that, the ‘big’ confrontation is a bit lame even if one appreciates the bravery of avoiding onscreen action.

The longest set piece is a bit like one in Cat People. Even with music added, it works almost as well. Mary runs down a street where sinister shadows turn out to be only those of lovers and noises that of an animal knocking over a trash can. She backs away along an alley wall only to bump into her pursuer waiting behind her in the opposite direction; he pulls a knife but in a striking aural cut the sound of the blade merges with the laughter of people merging from a bar, which she uses as cover to get away. And then there’s Mary in the shower being threatened by the shadow of someone which Alfred Hitchcock may have remembered; certain elements may have informed Rosemary’s Baby too, principally the idea of satanists who look like ‘ordinary’ people and could live next door. It’s interesting to see a heroine who at one point wants to give up and has to be talked around, and Kim Hunter, in her film debut, is an appealing, innocent presence. She should really have been top billed, seeing as she’s in most scenes, rather than Conway. While he gets most of the best lines, like, as he passes two flights of stairs, “I prefer the left, the sinister side” [I’d be the same], Conway seems slightly lost in places, something which isn’t surprising when his character initially seems rather sinister and curiously intent on keeping Jacqueline hidden away, yet then joins the group trying to find her and only reveals one major thing which he could have easily mentioned earlier; his reason for holding this back is weak. Jean Brooks as Jacqueline only appears in three scenes but she has such a hypnotic, almost ghostly, presence in this film. Nicholas Musuraca’s cinematography employs the usual incredible use of shadows, while Roy Webb’s score is appropriately gloomy; he has an emotive main theme but relies more on dissonance and single chords. And what Hollywood movie score of the time finished on a minor chord?

The use of the Lord’s Prayer seems out of place, it seems silly that these clever killers would cower before some words from the Bible, though maybe it was inserted to placate the MPAA. But the last scene is poetically moving without actually being sentimental, as Jacqueline, on her way to hanging herself, approaches her apartment and has a brief exchange with her neighbour Iris who’s leaving hers. The latter is very close to dying of some illness, but is nonetheless on her way to one final night out on the town. The contrast between the two packs quite a punch and I was left hugely moved as I only then remembered what Mary was going to do next; kill herself. I can only imagine that the puritanical MPAA allowed this [as well as the lesbian element] because it thought that this was an appropriately sordid end for a female sensation seeker. Of course to everyone now it probably just seems like we’re being told that death is a sweet release from a meaningless existence. I don’t think I’ve seen for some time a film which presents more effectively our dread of loneliness and alienation, Jacqueline’s loneliness being the strange but not at all uncommon kind that can exist when you’re continually surrounded by people. The feeling of creeping despair seems genuinely existentialist while you watch it, a statement on how things really are according to Lewton. And it would have been even more so if they’d kept in the original final scene, which had the unlucky-in-love Jason quote something suitable miserable that he’d just written, even if it’s still suggested that Mary, with her integrity, courage and seeming ability to have meaningful relationships, might be okay. While undeniably fascinating, I don’t think that The Seventh Victim is quite the masterpiece that some seem to think, but it’s very possible that repeated viewings may one day change my mind. It’s certainly a film with a very distinctive vibe and effect.

Be the first to comment