A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Directed by: Georges Méliès

Written by: Georges Méliès

Starring: Bleuette Bernon, Georges Méliès, Jehanne d'Alcy, Victor André

FRANCE

LIMITED EDITION WITH AUTOBIOGRAPHY AVAILABLE ON 21st SETPTEMBER, from ARROW ACADEMY

RUNNING TIME: 13 mins + 66 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

At a meeting of the Astronomy Club, its president, Professor Barbenfouillis, proposes an expedition to the Moon. After some dissent, five other brave astronomers – Nostradamus, Alcofrisbas, Omega, Micromegas and Parafaragaramus – agree to the plan. A space capsule in the shape of a bullet is built, along with a huge cannon to shoot it into space. Landing safely on the Moon, the astronomers have to deal with a variety of strange phenomena from snowfall caused by the god Phoebe to the insect-like inhabitants of the Moon….

One of the many, many things I loved about Hugo was that much of it concerned one of cinema’s great pioneers; George Méliès, though sadly it was something of a flop at the box office so not nearly enough people learnt of this amazing guy and were encouraged to check out his work, some of which was shown in the film, including clips from A Trip To The Moon. This is probably his most enduring work, even if he didn’t consider it to be that good and cited the far more serious and seemingly very dark Humanity Through The Ages as the film he was most proud of. It contains an image – the Man in the Moon with a rocket in his eye – that is iconic and one which must be one of the most popular of those movie shots which many are aware of but don’t know where they actually came from. Seen today, it’s still a delightful experience. Méliès wasn’t the first person to make movies but the former magician and toy maker was the first to really explore the cinema’s potential for fantasy, for showing the punter things that could definitely not happen in real life, to employ trickery to realise the strange and the wondrous, as well as significantly advancing the nature of movie story telling. Basically, without Méliès, the science fiction, fantasy and perhaps even horror genres may not have developed in the way that they did; this might sound like a ridiculous statement, but I genuinely believe it. His work may seem like little more than innocuous flights of fancy these days, his plots seem little more than an excuse for a series of often random happenings, his special effects may seem absurdly primitive to someone raised on CGI and place his work closer to the stage play than the motion picture, but it retains considerable charm and one has to love Méliès’s unbridled imagination.

Méliès cited Jules Verne’s novels From The Earth To The Moon and Around The Moon as the sources that inspired him to create A Trip To The Moon, though the second half seems to be partly derived from H. G. Wells’s First Men In The Moon, while a mushroom forest may have been taken from Verne’s Journey To The Centre Of The Earth. It was a much more costly production than Méliès’s previous films, this being largely because of the mechanically operated scenery and the Selenite costumes. Méliès himself sculpted prototypes for the heads, feet, and kneecap pieces in terracotta, then created plaster moulds for them. Actors went uncredited, a common thing for the time. The film was widely seen, yet Méliès hardly saw a penny from it. This was down to rampant piracy. He sold a print of the film to the Paris photographer Charles Gerschel for use in an Algiers theatre, under strict stipulation that the print only be shown in Algeria. However, Gerschel sold the print, and various other Méliès films, to the Edison Manuafacturing Company employee Alfred C. Abadie, who sent them directly to Thomas Edison’s laboratories to be duplicated and then sold on. Some prints didn’t even have his name on them, including all American ones for half a year. He set up a company to combat this and made some more films, but eventually they became less popular, Méliès failing to move with the times. What we’re told in Hugo is right; he was forced into bankruptcy in 1913 and, in a fit of anger and frustration, he melted down many of his movies and then became a toy salesman at the Montparnasse train station. A Trip To The Moon disappeared into obscurity but was rediscovered in 1930 when Méliès’s importance to the history of cinema began to be recognised. An original hand-coloured print, only a few of which were made, was discovered in 1993.

We realise right away that no attempt at reality is being attempted when we see all these astronomers dressed like wizards and their telescopes become stools. Once the plan to go to the Moon is agreed upon, we get a highly ambitious shot for the time where some people on the right hand side of the frame look out at funnels belching out black smoke as the ‘rocket’ is being made, before fire seems to erupt out of the ground before them in what seems to be a jab at the Industrial Revolution. The astronomers embark and their capsule is fired from the cannon with the help of ‘marines’, most of whom are played by a bevy of young women in sailors’ outfits. The Man in the Moon watches the capsule as it approaches, and it hits him straight in the eye. However, we then cut to a shot of the lunar surface and the rocket landing on it in what must be one of the screen’s first examples of non-linear story telling. The astronomers get out of the capsule without the need of space suits or breathing apparatus and watch the Earth rise in the distance before unrolling their blankets and sleep. As they sleep, a comet passes, the Big Dipper appears with human faces peering out of each star, old Saturn leans out of a window in his ringed planet, and Phoebe, goddess of the Moon, appears seated in a crescent-moon swing. The astronauts don’t see any of this, but they do soon find themselves having to contend with lots of insectoid Selenites who may be easy to kill but who outnumber the earthlings considerably. Méliès probably knew that, for example, one cannot fall off a cliff on the Moon through space to land on Earth, but he was never trying to be realistic anyway. He was just trying to put on a good show, to take film-goers on a journey and show them things they’d never seen before – before concluding matters with what may have been a jab at Imperialism!

It’s a shame that the explorers’ first reaction to encountering Selenites is not to try to communicate or understand them but to batter them with their umbrellas, though this was partly repeated in the 1965 film of The First Men In The Moon and one wonders again if Méliès was intending some political commentary here. The painted backdrops merge seamlessly with the constructed portions and props, creating locations with some depth in a surreal, dream-like world. It’s possible to work out how the special effects were done while still admiring them. Many were created using the substitution splice technique which Méliès discovered by accident when some film stopped and when it restarted the visuals had jumped ahead to being different. The camera operator would stop filming long enough for something onscreen to be altered, added, or taken away. Méliès would then splice the resulting shots together to create things like the disappearance of the exploding Selenites in puffs of smoke. Most of the time, it doesn’t look half bad. When we approach the Man in the Moon, it seems like all they’ve done is simply pull an actor covered up to the neck in black velvet towards the screen. Multiple exposures are used to put together an underwater sequence and the fish swimming in the foreground create an almost 3d-like effect. Certain devices like the descending portions of scenery to enhance the effect of the ‘Earthrise’ look clumsy but audiences of the time would have been totally enthralled – as I think you will be if you’ve never seen this. A Trip To The Moon retains much of its fascination, its charm and its energy.

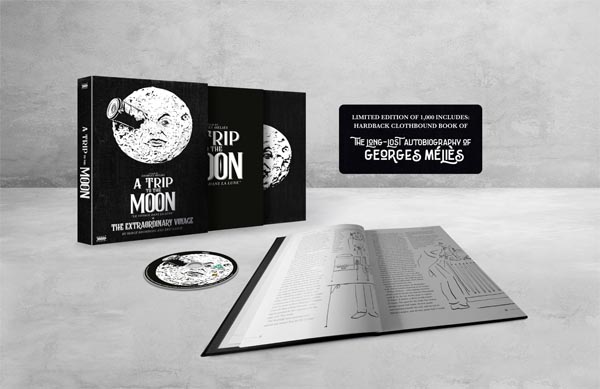

ARROW STORE EXCLUSIVE LIMITED EDITION CONTENTS

Limited Edition of 1,000 copies

Deluxe limited edition packaging featuring newly commissioned artwork

214-page hardback casebound book of Georges Méliès’ autobiography, previously unpublished in English

BLU-RAY

High Definition Blu-ray (1080p) presentation

The film is available to watch in both its black and white and colour versions. I hadn’t seen it in colour, so that was the option I chose. Obviously there’s much print damage and the hues fluctuate considerably, but you can still see the beauty in the colouring. It must have been gorgeous to look at in 1902 but it’s still rather gorgeous now.

Original uncompressed Stereo 2.0 and 5.1 surround audio

Optional English subtitles

Multiple scores by world renowned composers

Arrow give us the option of four soundtracks. The electronic one by Jeff Mills which automatically plays over the colour version is ambient in nature and pretty atmospheric if highly repetitive. The black and white version automatically defers a score by Serge Bromberg who co-wrote and directed the An Extraordinary Voyage documentary also in this set. Performed entirely by piano, it’s the most authentic-sounding soundtrack to me. Bromberg also narrates over his score in another option, telling us what’s happening, something which may sound pointless but which actually happened a lot in very early cinema. Then we have Dorian Pimpernel’s [what a name] score which doesn’t go with the visuals much but which is my favourite as a listening experience, sort of ’70s prog rock in sound combining electronics and instruments.

Le grand Méliès (1952) – a short film directed by Georges Franju about the life and work of Méliès [31 mins]

Flicker Alley released A Trip To The Moon twice on Blu-ray on Region ‘A’. Arrow’s version loses two other Melies films and a bit about the band Air who provided a score for that release, but adds Le grand Méliès as well as a newly produced featurette. Le grand Méliès begins by telling us that it’s entirely comprised of archive footage, which it obviously isn’t; George’s son Andre plays him in the many scenes when we supposedly see George, either in his toy shop entertaining children, in his [recreated] studio or presenting his magic shows and films. Nonetheless this is a nicely put together piece that begins in the chateau where he spent his later years, with shots of his wife Jeanne d’ Arcy and even a man playing on the piano a song that George wrote for her which becomes the musical ‘theme’ of the film, before flashing back to his early years. We get recreations of some of his magic, like seeing flowers quickly bloom, and clips from some of his movies which really do want you to go and watch all the ones that have survived. It’s available here in both French and English versions. The French one is much more poignant because it’s narrated by George’s granddaughter Francois Lallemont; the English just has a standard narration track

The Innovations of Georges Méliès – new video essay by Jon Spira exploring A Trip to the Moon and Méliès’ career [15 mins]

Here we get a potted account of Méliès’s career, with more juicy film clips which led to me staying up rather late watching the films of his that were on Youtube [I’ve been aware of Méliès for some time but never explored his work until now]. I find the slight macabre emphasis of much of his stuff, even if always in a playful fashion, particularly interesting; lots of skeletons, demons, and losing of heads and occasionally other body parts. Some moments like multiple doubles of himself forming still look quite good, while Spira points out that 40 years later Lon Chaney was changing into the Wolf Man using the same techniques that Méliès used to transform himself. The devices are explained in detail and it’s also pointed out how innovative he was in other ways. However, this featurette does come across as a mini version of the next feature.

An Extraordinary Voyage – Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange’s 2011 documentary on the film, its rediscovery and preservation for future generations, featuring interviews with Costa Gavras, Michel Gondry, Michel Hazanavicius, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet [66 mins]

The famous shot of the rocket in one of the eyes of the Man in the Moon opens this documentary which largely covers already covered ground but in considerably more detail. We get even more stuff on his early life, his films along with more clips, and his decline. But we also get clips from other movies of the period to add context, plus delights such as a recreation of the filming of a scene in A Trip To The Moon starring Tom Hanks as Méliès, and lots of interesting information. Méliès and his crew were limited to only four hours within which they could shoot, 11am to 3pm when the sun was directly shining over his studio which had a glass roof. And he had 300 women hand tinting his productions at any one time. Gondry, Jeunet and company tell us with great clarity why Méliès went out of fashion, which was for several reasons, one of them being that reality was surpassing fantasy in some areas. When real footage of the North Pole was seen in cinemas, it was understandably far more exciting to patrons than Méliès’s The Conquest Of The Pole with its fake scenery, even if Méliès’s North Pole had a giant and the real one didn’t. But I like to think that he could have continued working in motion pictures, maybe doing special effects for other productions, if various other things hadn’t caused things to go terribly wrong for him. At least he lived long enough to see his work rediscovered and his star rise again.

In fact I found the later sections of An Extraordinary Voyage to be the most interesting. We get glimpses of Méliès imitations. notably a remake [or maybe a ripoff] of A Trip To The Moon. We learn that Franju and some other directors were able to save some silent films when around three quarters of them were destroyed by the studios with the advent of sound which remains an act of cultural vandalism. And we get a great deal of time devoted to the restoration of A Trip To The Moon, and it’s absolutely fascinating learning and seeing how they underwent what became such a lengthy and risky [things could have gone terribly wrong] process. Even if you don’t generally go for this very technical stuff which can get very dry, I think you’ll be surprised how interesting and even exciting it is. This is an essential watch for really anybody seriously interested in cinema.

2020 re-release trailer

BOOK

The Long-Lost Autobiography of Georges Méliès: Father of Sci-Fi and Fantasy Cinema

Available for the first time since 1961, finally translated into English by Ian Nixon, with annotations and supporting material by Jon Spira, Méliès filmography, illustrations by Lucy Collin, interviews with filmmaker Serge Bromberg, silent film expert Bryony Dixon, and filmmaker Michel Gondry

I wasn’t able to review the above book, but I’d imagine that it’s an excellent read, while the price for this very limited set isn’t considering how expensive this book would probably normally be on its own. Highly Recommended.

And I’m now off to cram in a couple more Méliès shorts before I go to work….

Be the first to comment