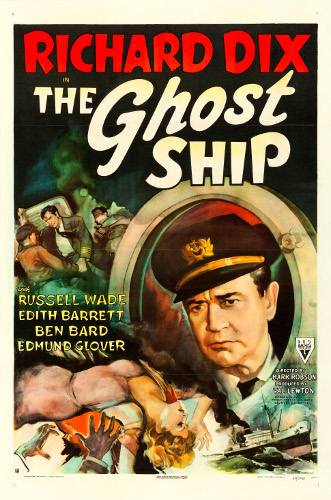

The Ghost Ship (1943)

Directed by: Mark Robson

Written by: Donald Henderson Clarke, Leo Mittler

Starring: Ben Bard, Edith Barrett, Richard Dix, Russell Wade

USA

AVAILABLE ON DVD

RUNNING TIME: 69 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Tom Merriam signs on the ship The Altair as third officer under Captain Stone. At first things look good. Stone sees Merriam as a younger version of himself and Merriam sees Stone as the first adult to ever treat him as a friend. Merriam even performs an emergency appendectomy when Stone is unable to do it. But when crew members begin to mysterious die, Merriam begins to think Stone is a psychopathic madman obsessed with authority. He tries to tell others, but no one believes him.…

So after a small break, I return with my reviews of the films which comprise the eight horror movies made during the ‘40s from producer Val Lewton, movies which have won praise from countless critics due to their subtlety, intelligence and complexity; and so far I can understand why, even if I didn’t find The Seventh Victim to be quite the masterpiece that many claim it to be. The title of this next effort is rather misleading, seeing as there are no ghosts in it – well not literally; one of the main characters is clearly being haunted by ghosts from a troubled past which we don’t really learn about. In fact there’s nothing supernatural going on in it whatsoever. Conceptually The Ghost Ship is the simplest of the films so far, a thriller set almost entirely on a ship where the captain might be mad and even a murderer, so much so that it might have felt like a breather for Lewton and director Mark Robson after the complexity and gloominess of The Seventh Victim. However, this hugely gripping exercise is pretty much a model in how to wring terrific suspense from very limited means, and it certainly has the Lewton stamp of quality all over it. However, its climax does seem to arrive awfully suddenly, as if we haven’t quite had enough build-up, but then this seems to have had the lowest budget out of all of these films. And, much like the previous films but especially The Leopard Man, it was quite ahead of its time in depicting of a psychopath with some nuance and even sympathy, and one who kills simply because he’s insane; to my mind only M did this over a decade before.

So The Seventh Victim, which was the fourth Lewton production, had been a commercial disappointment even though it still made money. RKO wanted Lewton to go back to the world of his biggest hit Cat People which had been the first in this series, and make The Curse Of The Cat People, while Lewton was interested in doing the supernatural comedy The Amorous Ghost. Eventually RKO production chief Charles Koerner suggested that Lewton make a horror film set at sea, utilising the studio’s existing ship set, built for Pacific Liner. Lewton, an amateur sailor, agreed and gave his idea to Leo Mittler who did the treatment after which Donald Henderson Clarke wrote the script, though Lewton significantly revised the screenplay and wrote many lines of dialogue himself. The Seventh Victim’s Mark Robson was assigned to direct, and much of the usual Lewton cast and crew returned. Shooting took place using just a single light source for every shot. Box office was good, but then the film was withdrawn because Lewton was sued for plagiarism the following year by playwrights Samuel R. Golding and Norbert Faulkner, who claimed that the script was based on a play that they’d written and submitted to Lewton for a possible film. Lewton disputed this, but the court ruled against him. RKO had to pay the authors $25,000 in damages and attorney fees of $5,000, and lost all future booking residuals which would extend to TV showings. The film was then unseen, only becoming briefly available for TV until it was withdrawn again, until 1993 when it lapsed into the public domain.

As our hero Tom Merriam, despite being told by a blind beggar that The Altair is “a bad ship”, boards his new place of work, a mute named Finn [sporting the unforgettable face of Skelton Knaggs] speaks to us some strange stream-of-consciousness narration about Finn and how he can, “see things he can never see, know things he can never know”. Of course this immediately makes things feel very ominous, and this narration returns at times throughout, adding a strange dimension to proceedings and then leading to a payoff in the finale. Merriam is a bit perturbed to find that his cabin is not only a mess, but that someone recently died in the bed mysteriously. However, things seem okay for a short while, with Merriam and Stone bonding. It seems that both have been lacking love and friendship in their lives and have survived the hard way. A swinging lamp reveals a collapsed crew member – ‘The Greek’ – who needs an appendicitis, but Stone can’t perform it, requiring Merriam to do the operation. Stone says that his refusal to perform it was due to fear of failure. Merriam’s clearly bright, but Stone is brilliant at talking his way out of things and making his case seem like the right one. When a huge hook on a chain sways back and forth, narrowly missing the heads of not just some crew members but from the looks of things cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca too in a nerve-wracking moment, Stone won’t let it be restrained because it’s just been painted – and Merriam goes along with Stone’s reasoning for this. However, when another crew member [an un-credited Lawrence Tierney in his debut] is crushed to death by the grain because Stone may have closed the hatch, Merriam changes his mind about his captain – but will anybody believe him?

Could Merriam be the mad one and Stone just a captain who runs a tight ship? I could have done with this ambiguity being maintained for a bit longer, but then this was only a 69 minute-long film. There’s a brief respite on the [fictitious] Caribbean island of San Sebastian which had previously appeared in Lewton’s I Walked With A Zombie [there are so many things connecting these films, some of which suggest a sort of cinematic universe while others are more oblique] where Merriam attempts to expose the Captain’s madness at a board of inquiry, but the crew all speak favorably of him, including the Greek, who credits Stone with saving his life. Merriam states his intention to leave The Altair, but winds up on her again anyway when he’s involved in a fight and somebody else – unaware of his intentions – brings the unconscious man back aboard before the vessel departs. Merriam wakes up on a ship where the other members of the crew refuse to talk to him and where he thinks Stone may try to kill him, especially when Stone seems to be everywhere, and that the lock on his cabin door has been removed. In one especially sinister scene, he rigs up a cord that will turn on his lamp if his door is opened; he turns the light off and goes to bed, only for the rocking of the ship to smash a plate in the darkness startling him and causing the door to swing open and set the lamp off. This is classic Lewton fright, both scary and rife with psychological suggestion. Things may seem less exotic, more realistic than we’ve had before, but Lewton and Robson are still able to employ their usual devices to get viewers on the edge of their seats, before giving us a pretty good knife fight with what looks like only minor use of stunt people and a surprising amount of blood. While there are other deaths that take place off-screen, the early chain crushing is surprisingly grim too, Robson dwelling on the poor victim’s fear and slow death. Subtlety isn’t always the name of the game here.

Of course the noir-ish cinematography is typically outstanding and gets progressively stronger in its use of blackness and shadows; even early on there is a constant sense of something sinister lurking in the shadows. The use of lighting from just a single source in every dark shot is most effective. However, the most interesting thing about this film has to be its killer, who unusually for the time is not motivated by greed or revenge. Instead, he’s become this way because of a lonely and sad life which finds some meaning when he becomes obsessed with authority and is able to lord it over others and even control their destinies. Because he’s willing to sacrifice his life for his crew, he believes that he has rights over their lives. Richard Dix convincingly portrays an early psycho killer who behaves normally in most circumstances but is actually a calmly functioning lunatic who casually plots the demises of crewmen that he feels are disloyal; yet we are bravely invited to sympathise with him, as we were much later with Norman Bates and many of his imitations. Halfway through, the film’s pace slows while we’re in San Sebastian and we’re introduced to a female character, that of Ellen Roberts [I Walked With A Zombie’s Edith Barrett, now without old age makeup], but her scenes are some of the most important in the story. Ellen and the Captain have been friends for 15 years, and probably more than that, but have been prevented from being together by two things; her marriage and The Altair. Finally she’s got her divorce through, but by now Stone is to consumed with his ship and he even confesses to her, “My mind, I don’t trust it anymore” and, “I can’t control my thoughts, my actions”. Through Barrett’s subtle acting, we can see that Ellen knows that Stone is now lost, not just to her but to reality.

I wouldn’t be surprised if some writers see a gay subtext concerning Merriam and Stone; I don’t at all myself though, even with me being used to the extremely subtle ways and codes with which homosexual characters and relationships had to be depicted many decades ago. Russell Wade is less bland than you might expect as Merriman, and the crew members add some colour, notably I Walked With A Zombie’s Sir Lancelot whose songs provide a counterpoint to everything else. Roy Webb provides another quite low key music score, consisting more of almost minimalist motifs rather than themes, which leaves most of the first half un-scored and even in the second half avoids histrionics. It’s fascinating to see how his work seems to be maturing with each film. And The Ghost Ship itself is quite fascinating. Yes, it being a bit longer would have helped, and there’s a wrap up which is oddly optimistic for Lewton and which initially struck me as being rather out of place in such a characteristically downbeat and melancholic film. I’d personally have concluded the film with Merriam in not as good a place as he seems to be, which might have added irony and weight to one particular line that Ellen says to him. But maybe Lewton felt that he ought to lighten things just a beat after the despair-filled ending of The Seventh Victim – and I can totally understand that.

Be the first to comment