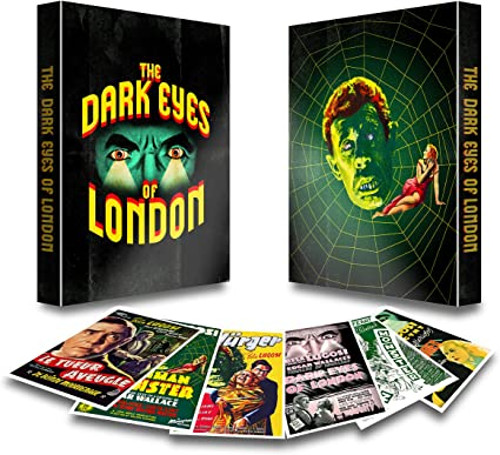

The Dark Eyes of London (1939)

Directed by: Walter Summers

Written by: Edgar Wallace, Jan van Lusil, John Argyle, Patrick Kirwan, Walter Summers

Starring: Bela Lugosi, Edmon Ryan, Greta Gynt, Hugh Williams

AKA THE HUMAN MONSTER

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: 11TH OCTOBER, from NETWORK RELEASING

RUNNING TIME: 76 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

The police are baffled by five drowned bodies turning up and their chief isn’t much pleased with their lack of progress. Meanwhile Insurance Broker Dr. Feodor Orloff loans a large sum of money to inventor Henry Stewart. The grateful Stewart asks if there’s anything he can do as a show of gratitude and Orloff suggests he makes a donation or, better still, pays a visit to The Dearborn Home for the Destitute Blind to see the good work that’s being done there. But once there, he’s murdered by Orloff’s super strong assistant Jake and his body is the next one found in the Thames with a letter in braille in his jacket pocket. His daughter Diana vows to find out who killed her father, while Inspector Holt finds himself partnered with Chicago’s Lt. O’Reilly in trying to solve the case….

Pulp writer Edgar Wallace was so prolific that in his heyday one of his publishers claimed that a quarter of all books in England were written by him. He also wrote many film scripts, easily the best known being the first draft for what was first called The Beast but which later became King Kong, though he died before he could finish it. As for motion pictures based on his work, they total a whopping 160. From what I’ve read, The Dark Eyes Of London is typical, a murder mystery with horror elements. Well, ‘mystery’ may seem like pushing it, since we find out what Bela Lugosi’s character is up to very early on, though seeing as this is Lugosi it would probably have been pretty obvious even to viewers in 1939, though it’s quite a well constructed story and provides a good twist near the end; it’s sort of a cheat really because something has been disguised by the use of audio, but otherwise it’s doubtful that anybody would have been fooled. I know I’m sounding vague, but it’s only because I don’t want to give it away. That would be a shame, because this is a really neat little thriller that’s well paced and well plotted, mixing police procedural, horror and comedy together pretty well. Perhaps it strains at times to provide a horror feel to what may have been much more of a light romp in its book form, but the blind institute setting is rather eerie and this film has one of Lugosi’s most sadistic moments, where his character uses some kind of electricity to destroy the hearing of one of his blind and dumb accomplices so that he won’t be able to hear the questions posed by the police, an act shown on camera too. The man himself is on quite restrained form, though the script can’t help requiring that his eyes glare and he briefly hypnotise two people, Dracula style!

The novel of The Dark Eyes Of London was written in 1924. In 1936 horror films were banned in the UK for nearly three years after Universal’s The Raven caused a great deal of fuss. 1939’s Son Of Frankenstein was the first one to be released, though production actually began on The Dark Eyes Of London in 1938 by Argyle Films, a company set up by some-time director, screenwriter and producer John Argyle, but was held up because of its gruesome content. The commercial success of the Frankenstein film caused production to proceed. Screenwriters Patrick Kerwin, Walter Summers, Jan van Lusil and Argyll himself simplified Wallace’s plot including reducing two Orloff characters into one. Shooting lasted eleven days at Welwyn Studios at Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire. The final scene involving Orloff’s demise required a seven-foot-deep tank to be filled with a concoction resembling river mud. A stuntman was lowered into the mess with a chain that allowed him to escape easily if he were sucked under, intercut with a shot of Lugosi’s head sinking. Lugosi did not submerge, but weights had to be tied to Lugosi’s ankles to keep his body sunk. The first British horror movie to be rated ‘H’ for horrific [adults only], it did fairly good box office though was retitled The Human Monster in 1940 for US release, something that happened to several of director Walter Summers’s films. It was briefly re-released in the UK in 1949 in a colourised version, with a few cuts to secure a ‘A’ rating, though these cuts were waived in 1953 when the film received a full release with an ‘X’ certificate. 1961 saw The Dead Eyes of London, a German remake which stuck closer to the book.

Stewart’s body shows up with braille writing in his pocket and a torn cufflink. A trick played on Grogan involving a pretend drunk who just can’t stop laughing being thrown into his cell leads Grogan to unknowingly reveal that Orloff is communicating with him in code. Grogan’s speciality being forgery makes Orloff even more suspicious than he was before, but there’s absolutely no proof, and he always seems friendly and eager to help, doesn’t he? The bodies were all as a result of drowning, weren’t they? It’s a mark of the film’s quality that we’re still quite engrossed as our cops gradually piece things together; after all, we know what Orloff is doing, but don’t know all the details yet. There’s an almost documentary feel to some of the scenes of the police looking at clues, but then the script goes and ruins the verisimilitude by having our two supposedly bright cops get our heroine to get a job with Orloff so she can snoop around. Seeing as Diana is the daughter of Orloff’s latest victim, it seems a very rash thing to do – surely Orloff would be suspicious? On the side of good it’s really all about our English policeman and our American policeman as the latter seems dumbfounded by the country he’s in, such as several killings taking place and not one of them being from a gun, or a female policeman, the latter cue for some mild sexism though this little subplot climaxes in a way that should make only the most humourless person smile. O’ Reilly’s willingness to smack somebody about with a truncheon is also turned into a joke. “There’s no third degree in this country, we catch our crooks by kindness” says Holt. Loud, brash and not too bright, O’ Reilly is a simple caricature, but he does provide amusement, and, even if Holt doesn’t really have much of a character, Hugh Williams and Edmon Ryan have genuine chemistry.

The pace speeds up as it should do, the final act prompted by Jake, who’s a brutal killer yet who has affection for the inhabitants of the care room and is genuinely hurt when one of them is hurt too. The conclusion combines two horror movie climactic situations that were cliched even in 1939, so even if you haven’t seen this film you’ve probably guessed how it ends. It’s fairly well done, especially because by now the use of darkness and shadows has increased hugely since the beginning. Director Walter Summers and cinematographer Bryan Langley seem to gradually ramp up the visual style. Initially things look quite pedestrian, the sparse sets showing up the limitations of the budget, but it gets more and more interesting, with some moments in the final quarter almost taking place in virtual darkness, something that may have hampered earlier releases of this film but which shows up fine on High Definition. Twice Summers uses the idea of showing violence at a distance through doorways; on the first instance we immediately cut away but on the second we’re allowed to see part of it, a strangulation in a bath tub. The way it’s shot makes us feel as if we’re there and which makes us feel uneasy, firstly because it seems like we’re actually watching the violence for real, secondly because we want to get closer but don’t like ourselves for feeling this way. Some shots of a corpse were probably the limit of what the BBFC would allow at the time and their realist look made me surprised they passed these shots at all. The desire to bring in a horror feel is most shown though the way that the blind institute looks like a mad scientist’s laboratory with steep 75-degree angle stairs, high walls and shots showing the blind at work on bizarre cane weavings on strangely mounted boards. Sadly the blind are mostly treated as strange, even fearful, figures.

There’s less time for romance to slow down the action than usual. Holt and Diana first meet when he waiting for O’ Reilly and Grogan and he tries to help her off a train. However, she trips over him instead, something which is amusingly followed up by a handcuff gag that’s so totally simple yet which can’t help but raise a smile. After this, we think that we’re going to get a screwball-type relationship between the two but it doesn’t happen, something which is either good or bad depending on your taste. I was disappointed that Orloff had a sinister female secretary who seems like she’s going to feature in later proceedings, yet then totally disappears from the film. In fact there do seem to be signs of substantial cutting, either of the script of the film itself, though this was quite common in horror films of the period and this one isn’t substantially harmed by it, unlike say The Devil Commands and The Ghost Of Frankenstein where the cuts cause obvious problems. And Orloff’s doings seem rather excessive considering all he’s really after is money, though he is “unbalanced”, something Lugosi, for better or for worse [he’s very effective at this yet it probably limited his career], was able to show very well. Yet The Dark Eyes Of London, while just falling short of being a classic, remains a rather good balancing act even when seen today. I’m genuinely surprised that it didn’t lead to a boom in British horror, something that didn’t actually happen for almost two decades.

SPECIAL FEATURES

Brand-new audio commentary with Kim Newman and Stephen Jones

Kim Newman and Stephen Jones discuss Lugosi’s work in the UK at the Edgar Wallace pub in London

US titles

US trailer

Image gallery

Limited edition booklet written by Adrian Smith

Limited edition O-card (Blu-ray exclusive)

Limited edition poster postcards (Blu-ray exclusive)

Be the first to comment