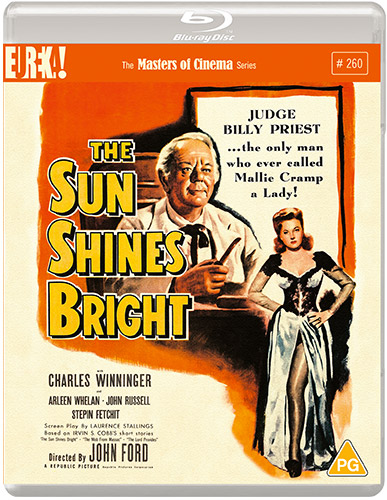

The Sun Shines Bright (1953)

Directed by: John Ford

Written by: Irvin S. Cobb, Laurence Stallings

Starring: Arleen Whelan, Charles Winninger, John Russell, Stepin Fetchit

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: 25TH JANUARY, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 102 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

In post-reconstruction United States, Confederate army veteran Judge William Pittman Priest sits on the bench in a small Kentucky town in 1905. An election for his seat looms, and Priest must balance his sense of what is right with his concern for his job. His opponent Horace K. Maydew is a Northerner and a reformer running on an anti-vice ticket. Priest has three other current pressing issues. He’s trying to find a job for the idle African-American boy Grant Woodford. The town Ne’er-do-well do well, Ashby Corwin, comes back from his latest travels with intentions to court Lucy Lee Lake, but this and the sudden appearance of an ailing old lady in the town could expose a secret concerning her mother. And a young girl is sexually assaulted and Woodford is blamed and arrested….

Despite having made such great movies as The Searchers, My Darling Clementine, Stagecoach, How Green Is My Valley and my personal favourite The Quiet Man, John Ford said that The Sun Shines Bright was the one that he liked best. Truth be told, I’d never heard of it until a few weeks ago when Eureka’s screener disc popped through my letterbox. Was this a neglected masterpiece, of was Ford just trying to be different? Well, I do believe Ford; it’s oozing that Ford love of people, that Ford sentimentality, that Ford interest in justice and that Ford liking for small communities, not to mention that Ford love of booze. It seems in part to be an exercise in nostalgia for a Deep South that never really existed, but these elements are accompanied by a slight sense of cynicism, even derision, which sometimes makes matters seem quite modern, though said cynicism doesn’t calculated, rather a natural part of things that maybe Ford wasn’t entirely aware of. Something that makes matters seem far less modern is the treatment of the African-American characters. The patronising handling of the majority of them can be forgiven as a misguided attempt at being progressive, but Jeff Poindexter, Priest’s supposed friend who’s really more of a slave, is a genuinely horrid caricature, the archetypal stupid, lazy black man. The inconsistency is bizarre but that’s Ford for you; just think of the widely varying treatment of Native Americans in his work. Ignoring that, this film is an amiable, rambling [despite its fairly short running time] affair where it seems that some of the scenes could have been put in any order. The intercutting and crossing over of the plots is a bit confusing at first, and the film is sometimes a bit cloying, but it’s hard to deny that it’s a heartfelt piece.

Irvin Shrewsbury Cobb was an American author, humorist, editor and columnist who wrote more than 60 books and 300 short stories, some of which were adapted for silent movies. Ford first adapted his work in 1934 with Judge Priest. Priest was a character Cobb wrote many short stories about, Ford’s film combining three. Despite being a hit, 20th Century Fox cut ten minutes, notably a scene of an attempted lynching, which irritated Ford immensely. This was the main reason for him revisiting the character two decades later, this time for Republic Pictures, a project based on three more stories which included another with a near-lynching, and one that he’d started planning in 1947 just after he’d completed My Darling Clementine. Charles Winninger replaced Will Rogers as Priest but Stepin Fetchit reprised his role as Poindexter. Scheduled to shoot over a period of thirty days, Ford wrapped it up in twenty-eight. The final production of Ford’s independent Argosy Films, its box office failure contributed greatly to Argosy’s demise and caused Ford to retire for over a decade. And, ironically, while the attempted lynching was left intact this time, eight minutes were cut elsewhere by Republic, and then a further three. The audio commentary identifies the bits that were cut, which were the opening sequence and several very small but usually important moments. The 91 minute cut became standard until the 102 minute cut one was accidentally discovered after preparing a video print. Republic Video had stumbled upon Ford’s personal copy, which had never been publicly viewed. The main print in circulation was thereafter the full version. Director Alejandro G. Iñárritu has said that this film was the main inspiration for his entire film career and that he watched it over and over as a child and used it, especially its morality and characterisations, as a model for the kind of films that he wanted to make.

A steamer, watched by two African-Americans, arriving in the town opens the film and another one leaving closes it, though that’s about as structured as this film gets. Our hero is introduced playing his old army bugle after he’s first got out of bed; he even blows the bloody thing out the window. Of course he’s trying to wake up his African-American friend/slave/whatever Poindexter who has a habit of falling asleep. Priest tells him to reach under his bed for his whisky which he partakes of frequently to “get his heart started again”. Yes, one can already groan even if you’re not one of those easily offended types, but Priest is still a great character; he may be a judge but he seems to spend all of his spare time either getting pissed with other members of the Confederate regiment he was in, or doing all he can to get people to vote for him, even if it means flattering ladies or not just letting some ex Union soldiers use their flag but parading into their building with it. There’s a scene in the courtroom where the boy Woodwood is asked to play something on his banjo; he plays a Union song which doesn’t go down well at all but a Confederate piece brings the house down and even gets half the town going. However, Confederate and Union people do all get on here, the rivalry is friendly except for Priest’s arrogant political opponent Maydew, just like whites and blacks – the latter seem absurdly happy in their slavery. If this was a Disney film we would probably not be getting the opportunity to see this film, considering their peculiar pretense that Song Of The South, a film that depicts a similar view of slavery, doesn’t exist. Yes, it’s an inaccurate portrayal, but that doesn’t mean it should be cancelled, and that film’s message is actually very positive. The next generation should know how fraudulent filmmakers and storytellers were on this issue.

Priest being asked to get the lazy Woodwood a job and his giving him one would have made sense even if Woodword was white, though one can still get annoyed by the idea of the paternalistic white man looking out for little black children. More to the point of the plot, isn’t it ironic that, if Woodwood hadn’t have been in the wrong place at the wrong time because Priest sent him there, he wouldn’t have been arrested because somebody molested this girl nearby? Meanwhile Ashby is interested in the girl he knew as a child, Lucy Lee. There’s a nice bit where she tells him that she’s still going to school and heads for the town school where she turns out to be the teacher. Indeed much of the humour is nicely gentle. Meanwhile Priest really wants to win this darn election which isn’t easy when his competitor writes and publishes nasty letters about him. There’s a sordid secret about Lucy’s family which Priest and many others know of, but Corwin has no idea, and he loses it when one guy taunts Lucy about this, causing a fight involving bullwhips to take place, while her grandfather denies that he’s her grandfather and then this practically dying old lady turns up wanting to see her. And the arrest of Woodford causes racial tensions to rise. A montage where we just see quick shots of several black characters and hear screams and gunshots is economy at its best, a highly effective example of the “less is more” approach. Then a lynch mob sets off to get Woodford whether Priest likes it or not, setting up a sequence that’s well staged but which doesn’t quite have the impact that it should. Of course the parallels with To Kill A Mockingbird throughout this subplot are obvious.

The dramatic climax seeming to occur just three quarters of the way through is a good example of the rather haphazard structure, with the big scene near the end being a funeral which is dwelt upon at length, though of course said haphazardness can have its rewards too, most notably it seeming more close to real life which rarely follows a conventional structure. Even if the way every subplot seems to resolve itself in a happy way grates a little, only the most hard hearted won’t feel any emotion in some moments towards the end where it’s all about Doing The Right Thing. I’ll leave you to discover all this for yourself. Charles Winnerger is very good at showing a person who both wants to keep the status quo but who also wants to write wrongs and move things forward. We clearly sense this conflict in him even when the script isn’t always doing a very good job of articulating it. We do get that he enjoys getting drunk with his mates more than anything else. A pair of dim trappers [one of whom is Slim Pickens] who carry their rifles everywhere, even into posh parties [nobody seems to care] are even bigger piss heads, yet Ford clearly loves these scruffy drunkards far more than the other neatly dressed attendees at a lemonade and strawberry festival. As to his views on black people at the time; well, he probably thought he was forward thinking, even if certain things such as the way they come to idolise Priest wouldn’t please some viewers today. Of course Poindexter remains a very ugly caricature, even for one as opposed to political correctness as I am, but it’s so ugly one wonders if Fetchit was deliberately exaggerating the portrayal for subversive effect, showing how ridiculous the stereotype, a stereotype that nonetheless constituted many white people’s views of black people for some time, was. And later on Ford made Sergeant Rutledge. Go figure.

The very final scene contains the second best [well, from what I’ve seen] version of Ford’s familiar “character leaving us through a door” device made most famous in The Searchers. Well, it makes sense; Ford and his screenwriter Laurence Stallings probably feel that a man of Priest’s decency would be a relic several decades later. There isn’t much in the way of great shots, but as usual for Ford there’s a purity to his way of filming, with great precision in character framing and use of surroundings, yet it’s the kind of precision you generally don’t notice unless you review movies and therefore watch them in a different way to normal folk. Cast wise, aside from Winnerger, Arlene Wheelan does very well as the harassed and troubled Lucy Lee, almost underdoing her visible displays of emotion which seem to make sense in context, and making good use of her very expressive eyes. Victor Young’s music score is the archetypal Ford score of folk tunes, pieces that seem like folk tunes and occasional drama. “Sweet Genevieve” shows up yet again and several times. As I began watching The Sun Shines Bright, I just could not comprehend why Ford liked it so much, but I grew to have some understanding of why he did even if I wouldn’t at all consider it to be a major work of his. It seems to depict an idyllic paradise of times gone by, a paradise that’s sometimes interrupted by trouble yet it’s trouble that always resolves itself in the best manner. Common decency always prevails. If you hate humanity right now, this film might inspire you to regain your liking of it. And for that, despite its problematic elements, it has distinct worth. And take note that, in the final scene, Priest goes to get his booze himself for once, rather than order Poindexter to do it. Priest has progressed.

SPECIAL FEATURES

1080p presentation on Blu-ray

This was previously out on Blu-ray in North America from Olive Films. Eureka have probably used the same transfer but given it a new encode. The level of grain is slightly thicker than one might expect, though I wouldn’t say distractingly so. The image is as detailed as you’d want it and the blacks are very vivid. Some minor evidence of print damage can be seen, but in general this is still a pleasing transfer.

Optional English SDH Subtitles

Brand new audio commentary by film historian Joseph McBride (author of Searching for John Ford)

McBride provides a typically dense track for another Ford film. Keeping biographies fairly short and not even providing very many of them, he regales us with facts and appreciation. He thinks that this is “a great film”, and does make a good case for this comment though I still don’t agree. We learn that Ford saw much of himself in the Priest character, and that he first tried to put the funeral scene in My Darling Clementine but wasn’t allowed. He also goes into the racial elements in detail, telling us facts like lynchings of African-Americans being banned from the screen for several decades; Fritz Lang originally wanted Fury to have a black man being lynched but wasn’t allowed. And Fetchit tended to play his kind of role often because that’s all that was offered. A snippet from McBride’s interview with Ford, which can be heard in full elsewhere, reveals his famous gruff and impatient nature – but then if you had people asking you the same questions about movies you made so long ago that you can’t remember much, wouldn’t you get annoyed too?

New video essay by Tag Gallagher [author of John Ford: Himself and His Movie]) [11 mins]

Gallagher goes for things that McBride doesn’t talk about much or at all, focusing on the visual. He points out that Ford has stage-like entrances for all his characters, that all of these characters has “a stage act”, and examines Ford’s brilliance at staging and shooting one particular scene where obstacles between two particular characters are cleverly used; it’s the kind of thing that we don’t always notice but assimilate on an unconscious level. Short but sweet.

A collector’s booklet featuring a reprint of Judge Priest short story The Lord Provides; a new essay by James Oliver; and an essay by Jonathan Rosenbaum

At times seemingly sloppily put together and dated in its racial attitudes, yet ‘The Sun Shines Bright’ exudes a warmth, a love of people and unabashed sentiment that’s hard to succumb too. Recommended.

Be the first to comment