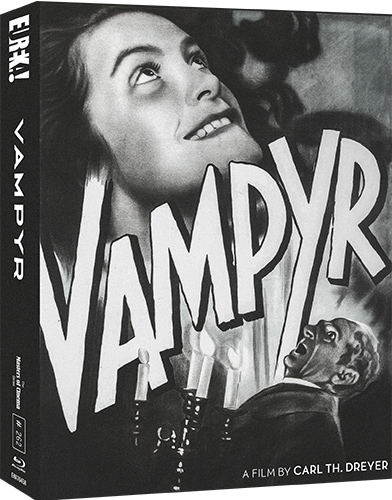

Vampyr (1932)

Directed by: Carl Theodor Dreyer

Written by: Carl Theodor Dreyer, Christen Jul, Sheridan Le Fanu

Starring: Julian West, Maurice Schutz, Rena Mandel, Sybille Schmitz

GERMANY/FRANCE

RUNNING TIME: 73 mins

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: 30TH MAY, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Allan Gray’s stay at an inn at the village of Courtempierre is interrupted by an old man who leaves a square packet on Allan’s table; “To be opened upon my death” is written on the wrapping paper. Allan takes the package and is guided by shadows to an old mill, where other shadows dance and a sinister old lady and a doctor seem to run the place. Walking to a manor, he sees that the lord of the manor is the same man who gave him the package earlier, but then he’s shot dead. Gisèle, the younger daughter of the lord, tells him that her sister, Léone, is gravely ill, and Léone is later found unconscious on the ground with fresh bite wounds. They have her carried inside. Allan remembers the parcel and opens it. Inside is a book about vampyrs….

Even if you watch as many films as I do, there are always those ones that you’ve always intended to watch but never got around to. In fact, as I type, I wonder exactly why I never made the effort to seek out Vampyr, seeing how much I love vintage horror and at times really do think that the first half of the 1930’s was the golden age of the genre. But then this dreamlike art house chiller, which I feel may have greatly inspired the weird vampire movies of Jean Rollin over three decades later, seems to exist separate from all the American classics of the period such as Dracula, Frankenstein, Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, The Island Of Lost Souls, etc., even if it is most definitely a horror film. In fact it contains a sequence which is more frightening than anything in those other films; it certainly gave me considerable chills, even if variations on it have turned up in a great many films since and I’m not sure if this was even the first film to depict one of many people’s greatest fears. The script by director Carl Theodor Drewer and Christen Jul tells a pretty simple story but seems to deliberately make certain details vague and add things just for surreal effect, the result being a near-endless parade of eerie imagery with deliberately disjointed editing which often threatens to burn its way into our subconscious, even if the pacing is very slow. The first and final thirds are really quite magnificent in their inventiveness and their atmosphere; the middle third is less interesting, basically stretching out a plot element that usually comprises ten or fifteen minutes of most versions of Dracula. Yet there’s still something hypnotic about the proceedings which were shot through gauze in the early morning, the resulting softness and shimmer adding immeasurably to the feel of a dream.

Dreyer decided to make a supernatural tale in late 1929, and as an independent production. He based it on two stories from J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s In a Glass Darkly; the lesbian vampire tale Carmilla which had many later adaptations, and The Room in the Dragon Volant about a live burial. The title was initially Destiny, then Shadows of Hell, then The Strange Adventure of David Gray. Aristocrat Nicolas de Gunzburg agreed to finance it in return for playing the lead role under the pseudonym Julian West. In fact few of the cast were professional actors and were found in shops, cafes and trains. Most scenes were shot in Courtempierre, France, where the discovery of a mill caused the changing of the climax from happening in a swamp, while cast and crew lived in the castle that was used. When cinematographer Rudolph Maté showed Dreyer one shot that came out fuzzy and blurred, Dreyer loved the look and had Maté shoot the film through a piece of gauze. Dreyer originally wanted Vampyr to be a silent film, then had the actors mouth their lines in French, German and English so their lip movements would correspond to the voices – which were mostly those of others – that were going to be recorded in post-production. The sounds of dogs, parrots, and other animals were created by professional imitators. The English version is lost and may never have even been completed, while the German version suffered censor cuts to a staking and the death of one of the villains. It sat on the shelf for nine months until Dracula and Frankenstein became hits, then still flopped. One showing in Vienna had audiences demanding their money back. When this was denied, a riot broke out that led to police having to restore order. In the USA, the film premiered with English subtitles under the title Not Against The Flesh; an English-dubbed version, cut by thirteen minutes, appeared three years later as Castle of Doom. The film’s failure caused Dreyer to have a nervous breakdown and even be committed to a mental hospital.

The image behind the credits already creates a strange effect. It looks like the silhouette of a human skull, but changes in size continuously. Text tells us of our hero Allan’s interest in the supernatural before he arrives at a inn and bang on both the door and a window before a young girl, a character who we never see again, finally answers from the loft. Allan gets his room and we get a sense that nighttime has arrived even though everything is too bright. But the fact that, whatever time of day it is, there’s the same amount of light soon becomes rather unsettling. The door of his room opens extremely slowly before the old man gives him the package, after which follows what’s quite simply a magical tour de force [despite most of it not having anything to do with the plot] of dark fantasy for about fifteen minutes, in which you can see the seeds of so much, from Carnival Of Souls to much of Tim Burton. As Allan makes his way along the side of a river, the reflection the other side has a figure moving much faster along the same locale. Inside a room of this rundown place a ghostly one-legged soldier and has his own shadow do things independently to him. Then we adopt the point of view as the camera as it tracks along a room, a corridor and into a larger room where ghosts are dancing to a shadow playing a violin. Allan’s and our introduction to the supernatural world he wanted to experience gets a sudden shift when a woman enters the room and cries “Silence”!, though he still walks past two coffins, one empty and one with somebody distinctly alive in it, before the more human fear of a creepy old lady and creepier doctor takes over. In his very strange laboratory the lady give the doctor a bottle of poison [one can’t help but chuckle how common these are in movies] , while Allan encounters an old man who totally misses seeing him before telling him that neither the girl nor a dog he heard exist.

With such an incredible setup, no film would probably be able to keep it up, though Vampyr‘s second and longest section begins strikingly, with the shooting of

Allan’s visitor with a rifle turned into an almost abstract series of silhouettes. In the house of the dead man, one daughter is being vampirised and the other begins to get to know Allan, while two servants lurk around looking sinister. Allan opens his package to find a book entitled THE STRANGE HISTORY OF VAMPIRES. A rather inordinate amount of time is spent on not just him but one of the servants reading it, so we learn all this important stuff which have the occasional change from what we’re used to; most notably, the victim of a vampire must be driven to suicide so his or her soul is damned, an interesting addition which I wished had been used in some later vampire films [well, maybe it was, I haven’t seen anywhere near all of them]. So that’s what that bottle of poison was for! We also learn of a certain Marguerite Chopin who may have caused an epidemic in another village 35 years ago though the doctors didn’t call it vampirism, and, as someone asks, “Why does the doctor only come at night”? Allan and the “Old Servant” set out to try to catch these two, but will they be in time? Léone is getting weaker and weaker, after all. How things unfold partly follow a predictable path, and partly don’t, with some narrative surprises being presented to us. This film must be one of the first to present a vengeful ghost on the side of good – well, if that’s what we’re really seeing?

The very Christian morality is expected, especially in a story which reduced to its basic level is about the saving of a soul, though curiously there’s no obvious religious imagery. The lesbianism of Carmilla which was expanded in most other cinema tellings is absent except for one startling little scene which I’m surprised got through. The bedridden Léone is feeling a bit vampiric, and stares at her sister Gisèle, following her passage from her bed to the door. The look is one of both undiluted evil and blatant lust, and there probably isn’t anything in The Vampire Lovers and Blood And Roses which has as much impact despite the qualities of both those films. Of course nothing is more unsettling than when Allan drifts off while sitting on a bench and dreams that, first of all, he’s a ghost, then that he sees himself been buried in a coffin before then adopting the point of view from inside. As his coffin is carried through the village, we cut back and forth from his face seen through a glass window to his point of view. The constant shots of the face, emotionless and visually trapped in the circular window like Allan’s whole body is trapped in the coffin, are incredibly unnerving and must have given many cinemagoers nightmares. The effect of the sequence is massively increased by, coming after so much music on the soundtrack, its silence. In terms of single images the early one of the villager with a scythe looking like the Grim Reaper may be familiar even if you don’t know much about the film, but there is so much else, some things making no sense on a conventional level like the skull that turns by itself, or bizarre playing with light and shadow by Maté, who really deserves as much credit as Dreyer for the film’s extraordinary effect. And is there a camera from 1932 that’s as mobile? Logic is constantly superseded by mood. Editing is often mismatched. A favourite device is to make us think we’ve adopted Allan’s point of view before we’re fooled. What dialogue there is often makes little sense, and sometimes people seem on the verge of saying something important then stop. Whole scenes appear to be missing, but maybe that was the intention.

West bears a resemblance to HP Lovecraft and has an off-kilter manner about him as he reacts to what’s going on around him. Acting-wise the high point is Sybille Schmitz, who portrays her slow transformation into a possible vampire with matter of fact subtlety, in a weird way providing a sort of realism to the peculiarity of everything and everyone around her. Wolfgang Zeller’s score avoids melody and focuses on small cells and mood in a way that seems quite contemporary. The main irritation with Vampyr, at least for this critic, is the intertitles that tell you what we could generally have deduced without them. They aren’t exactly harmful, and are only in the first third, but comments like “What was going on? What secret was unfolding?” do temporarily interrupt the incredible spell that the movie has cast, and I wonder if a version which removes them would have an even greater effect. The book reading, as previously described, is a bit too long too. But this is still a strikingly bold and unusual piece of cinema, especially for its time, which creates a low level chill right from the beginning but maintains it throughout its running time, even during a few longuers in the middle. It’s even there in the final beautiful images of escape and rural beauty, reminding us of what those opening intertitles said, “The line between the real and the supernatural became blurred”, as well as, in its cutting to a scene of death happening at the same time, showing us two versions of going into the light.

SPECIAL FEATURES

Limited Edition Hardbound Slipcase [3000 copies]

All-new 2K digital restoration of the German version by the Danish Film Institute, completed in 2020 after an extensive decade-long restoration process, with uncompressed mono soundtrack

Prints of Vampyr tended to look really poor until comparatively recently, so I’m so glad that this was my first viewing. For the most part, the film’s battle between brightness and darkness, between light and shadow, comes out beautifully, with blacks containing virtually no crush and grain evenly managed. That being said, this was pieced together from several different versions so a few shots and short scenes do look very blurry, but there’s very little visible print damage, which seems to have been very present in earlier digital releases. So not reference material, but still pretty impressive for its age. However, this being the German version, it has shots in two scenes missing. It seems that sound issues meant that they could not be properly restored, but surely they could have still been reinserted unto the film as another viewing option?

Optional unrestored audio track

Audio commentary by critic and programmer Tony Rayns

Eureka’s release includes all of the special features from Criterion’s Region A except for a radio interview, plus one new featurette. The two commentaries are quite superb. Rayns usually pauses during his tracks, but here he never stops as he analyses the film and in particular its visual style, saying that it “centres around subjectivity” and gives us “mental images rather than physical images”, while claiming that the scenes that Allan isn’t present at could be wonderings of his mind, yet also likens Vampyr to a play with its offscreen events and spaces. Rayns is terrific in describing the way the film works, yet still gives us some information such as de Gunzburg disliking Nosferatu and wanting something very different.

Audio commentary by filmmaker and Vampyr fan Guillermo del Toro

While I’ve been disappointed by most of del Toro’s recent work, I still love to listen to him, and here his enthusiasm almost bursts off the screen as he discusses a film he loves, beginning by saying “This is not a scholarly dissertation, this is the equivalent of inviting a fat Mexican into your house to feed him, then you have to listen to him for a mercifully short time” yet packing his track with intelligent interpretation. He views the film, whose story he rightly says is “quite easy to follow”, as being based on the idea of the momento mori, connects it to Dreyer’s Lutherism, and sums it up as being about “death of the soul, not the body“, yet admits that trying to decipher every image is not a worthwhile exercise. This is fantastic stuff all the way through.

Visual essay by scholar Casper Tybjerg on Dreyer’s Vampyr influences [36 mins]

Actually this covers many aspects of Vampyr, giving us interesting facts like Dreyer saying that he wanted to make “a commercial film”, but later on said that he “wanted to make a film different from all other films”, so the concept changed greatly. One nice story is when Dreyer’s location scout Elian Tayah found a factory and had to tell the owner who was going to renovate it not to do so, it was perfect as it was . Dreyer and art director Herrman Warm appear or are heard in interview snippets, some paintings that may have influenced Dreyer are shown, and cut scenes are mentioned along with the removed footage from the German version. One scene kept in would have told us why somebody suddenly mentions some dogs. A good featurette overall, even if some of the information has already been covered in the commentaries.

Carl Th. Dreyer [1966] – a documentary by Jörgen Roos [30 mins]

Footage of Dreyer at the Paris premiere of his last film Gertrud in 1962, with words from Francois Truffaut and Henri Clouzot, is then followed by Dreyer talking a bit about all of his films along with clips. The Vampyr material was in the previous extra, but it’s great to get this sampling of Dreyer’s ourvre; he seems to be one of those filmmakers who altered their style frequently. His most famous film, Jean D’Arc, we’re told was inspired by finding a handwritten document in a library from the 13th Century about her trial, while on Odette he had the canteen lady design the movie’s kitchen before he removed every object one by one until he felt it was right. This may inspire you to seek out some or all of those other films. It has with me, none of which I’ve seen before.

New video interview with author and critic Kim Newman on Vampyr’s unique place within vampire cinema [22 mins]

Newman can’t help but repeat a lot that’s already been said. But he does put the film in its historical place; it came out when silent films were having their last hurrah with epics like Napoleon being flops, accurately describes Vampyr as one of those films which is either a tedious bore or hypnotically frightening depending on one’s mood, and remarks that there’s very little of Carmilla in it. He also calls The Lost Boys “terrible”. I wouldn’t go as far as that, but I do consider it rather overrated.

David Huckvale on Wolfgang Zeller: New video interview with music and cultural historian David Huckvale on the film’s score [36 mins]

This surprisingly in-depth examination of the score goes through the whole film, beginning with a look at Zeller’s career which included scoring the nastiest of the Third Reich’s anti-Jewish movies Jud Ross, something he later regretted and even destroyed the score. Then we have a dissection of the main titles before looking at most of the successive cues. Huckvale points out the influence of German romantic opera including some borrowings, and tells us that one particular chord, the tritone, was actually banned in western music for some time because it was considered so sinister.

David Huckvale on Sheridan le Fanu: New video interview with music and cultural historian David Huckval [11 mins]

We aren’t told much about Le Fanu’s career, but we do learn that Dreyer and Jul perhaps used more of Le Fanu than it at first seems, in particular an interest in spirits he’d shown in some stories.

Two deleted scenes, removed by the German censor in 1932

So here are the shots on their own of a stake being hammered in and a victim’s agony as he’s killed in a rather unusual way. Their omission from the film doesn’t harm it, but it would have been to have had them put back in anyway.

The Baron: short 2008 documentary about Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg by Craig Keller (14 mins]

Here we learn about the film’s star and producer. His family fled Russia during the revolution, he toyed with being an actor in Hollywood, and finally found his calling in high society and fashion, eventually joining Vogue where his apprentices included Oscar de la Renta and Calvin Klein.

Optional English subtitles

A 100-PAGE BOOK – featuring rare production stills, location photography, posters, the 1932 Danish film programme, a 1964 interview with Baron Nicolas de Gunzberg (producer and actor “Allan Gray”), an essay by Dreyer on film style, and writing by Tom Milne, Jean and Dale Drum, and film restorer Martin Koerber [3000 copies]

‘Vampyr’ is a unique horror film even if you appreciate that it’s from a time which was full of them. Eureka more than does it justice in a packed release. Highly Recommended!

Be the first to comment