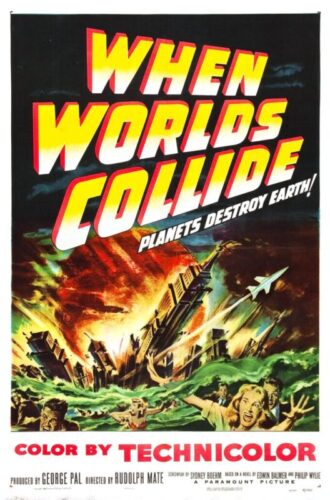

When Worlds Collide (1952)

Directed by: Rudolph Maté

Written by: Edwin Balmer, Philip Wylie, Sydney Boehm

Starring: Barbara Rush, John Hoyt, Peter Hansen, Richard Derr

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY, DVD and DIGITAL

RUNNING TIME: 82 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Pilot David Randall flies top-secret photographs from South African astronomer Dr. Emery Bronson to Dr. Cole Hendron in the United States. Hendron, with the assistance of his daughter Joyce, confirms their worst fears: Bronson has discovered that a rogue star named Bellus, accompanied by an Earth-sized planet named Zyra, are heading towards Earth and, while in eight months time Zyra will just miss our planet, Bellus will destroy it nineteen days later. However, the United Nations scoffs at his claims and rejects his plea for the construction of “arks” to transport a lucky few to Zyra in the faint hope that humanity can be saved from extinction. Fortunately some independent financiers offer to put up the money for a space ark in return for being able to select the passengers….

I was originally just going to review The War Of The Worlds in its 1953 incarnation, but in the course of writing my review of that film I became very interested in viewing producer George Pal’s previous effort as well, something that I hadn’t done in around a couple of decades. In fact all of Pal’s science fiction pictures probably bare re-watching, even The Power which isn’t well thought of, but let’s get to those another time [I’ve already done my personal favourite The Time Machine]. For now we have his very flawed but also very interesting disaster epic which certainly wasn’t the first film to have the Earth be threatened with destruction. Such films date back to the 1920’s, but this is probably the oldest one which is relatively well known, at least among science-fiction buffs. And a curious movie it is, one that probably seemed extremely naive even in 1952 but which appears hopelessly so now, though the way that it seems so sincere gives it a distinct charm which was certainly not unappealing to the Doc, even though it may also just make some first time viewers laugh or tut or feel sick. Surprisingly sparing in big special effects sequences, something no doubt made necessary by the budget, it focuses primarily on a very small group of characters who are all involved with leaving our planet before it’s destroyed, while also presenting a very odd mixture of science and religion. A lengthy pan along some of the books that the group leaving Earth are taking with them, which reveals The Bible as the very first tome before showing some infinitely more useful books of a scientific nature, sums up the film’s attitude perfectly, though Pal was himself a very religious person so one should probably expect a subject such as this be a rather Christian take. There’s also a hell of a lot of dramatic and moral illogicality in the story, along with a corniness which shows slight signs of being aware of itself, but at least the viewer will be left thinking about deep subjects such as the nature of mankind and which people are more valuable than others.

In the bestselling novel by Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer, Earth is doomed to destruction by the approach of two rogue planets which make two passes instead of one, the first one destroying the Moon along with other disasters left unrealised by the film adaptation. Cecil B. DeMille considered filming it and its sequel After Worlds Collide in 1933, but no script was written, though the film rights were held on to by Paramount. In 1949 George Pal purchased them. His version was originally to be directed by Irving Pichel who’d just made The Great Rupert for Pal and was about to make Destination Moon too for him, with that film’s scriptwriter Rip Van Ronkel hired to pen the screenplay. It would be the first film made under a three-picture deal between Pal and Paramount, but the latter two were never even scripted. Pal envisaged an incredibly lavish production, but he had to scale back his plans when the budget was cut despite Destination Moon having been a major hit. Sidney Boehm’s screenplay followed the basic story of the book, but added a love interest and removed a by-then dated subplot involving a search for for a material from which rocket tubes capable of withstanding the heat of the atomic exhaust could be made. The. final shot of the surface of a brave new world was intended to feature model work, but when Pal did a painting from which the model builders were intended to use as a guide to work from, Paramount deemed the painting to be satisfactory. Rudolph Mate ended up being the director of what was a big commercial success. Several times Pal unsuccessfully tried to set up a sequel based on After Worlds Collide, while in the late 1970’s, producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown planned a remake which would have had a script by Anthony Burgess: it eventually metamorphised into 1998’s Deep Impact which also took inspiration from the 1993 Arthur C. Clarke novel The Hammer of God; the finished film didn’t acknowledge these sources since it was judged as being different enough to not require it.

Pal liked to have dramatic titles and the sequence here is typical, simple but effective, blazing fire filling the film screen behind the credits before it’s replaced by smoke rising into the night sky. Then we get – ahem – well at least the film states its mindset right away – quotes from the Book of Genesis being both shown and narrated, all of which describes God’s decision to wipe out humanity because of how bad it’s become. We now expect plenty of parallels with the story of Noah, though there don’t turn out to be quite as many as I remembered there had been. We cut to the inside of a South African observatory where three men are conversing. “If our calculations prove to be correct, this is the most frightening discovery of all time” is the first line of dialogue that we here, and a wholly accurate one. Dr. Emery Bronson has a plan to get this information to the right people. “It won’t be necessary to tell Randall what he’s carrying” he says, but then he has a “lack of curiosity” anyway so it should be alright. Randall is introduced auditioning for the mile high club in the cockpit with a steward; he’s obviously just a guy after money and fun. He gets given his job and succeeds in carrying it out despite a newspaper reporter being happy to pay increasingly more money for what’s in the brown briefcase. He’s met in New York by Dr. Hendron’s daughter Joyce, who thinks he knows what he’s been transporting, and then Dr. Tony Drake, who doesn’t know either. Some calculations done from the photographs, largely by Joyce herself, reveal that yes, we are doomed. The United Nations lot either don’t believe the truth or don’t believe that ships can fly in space, which of course wouldn’t have been unbelievable to 1952 audiences, though we do get a major technical gaffe here which is perhaps surprising seeing how Destination Moon tried to be as scientific as a 1952 film about traveling to the moon could ever be. We’re supposed to believe that a number of “arks” which can fly through space could be built in just eight months!

Now we need to remember that we’re in 1952, so there has to be a romance, and quite possibly a love triangle. Here we have Randall, Drake and Joyce. The latter two are engaged and have clearly been sweethearts for a very long time, but now the cool Randall, so cool that in a restaurant he lights his cigarette by setting fire to money notes which he puts into a small heater on somebody else’s table, has come along and messed things up. She dances with Drake, but her eyes are on Randall. It’s all actually quite well played by the three leads; Peter Kerr, Barbara Rush [soon to be frightened by aliens in It Came From Outer Space], and Peter Hansen, and well enough worked out by Boehm so it becomes very important in terms of the bigger picture, even though the scenes devoted to this are thankfully kept to a minimum. The emphasis is on a community of people working incredibly hard so that some humans can escape the destruction of Earth [and we know quite early on that this cannot be prevented so I doubt I need to type spoiler warnings], even as newspaper headlines say that all this Doomsday stuff is nonsense. Two wealthy humanitarians arrange for a start to construction and a lease on a former Army proving ground to build an ark. To finance the rest, Hendron meets wheelchair-using business magnate Sidney Stanton. Stanton demands the right to select the passengers in exchange for his money, but Hendron insists that he’s not qualified to make those choices; all he can buy is a seat on the ark. Stanton capitulates. Groups in other nations start building their own spaceships. A good example of this 85-minute film’s economy is when we cut to a piece of paper stuck on a wall which says that martial law has been brought in; we don’t need major scenes full of extras now to show us this. Zyra causes havoc around the world, but the emphasis remains on our group. Wil they build the spaceship in time? How will the passengers be selected, and how will the losers react? There’s only room for 44 people, after all. And what is Stanton really up to?

We see a quite realistic model volcano erupting [some shots from this later turned up in The Time Machine], and a very impressive few seconds of New York being flooded, employing model work rather than the matting of real shots of places with special effects, but on the other hand there’s also a shot of the city immersed in water which is just a normal painting, not even a matte painting. I’m sure that this was down to tight Paramount’s fault, so we can’t really blame Pal, though cutting the shot shorter would have helped. Elsewhere real news footage from around the world helps out, but the titular collision of worlds takes place off-screen, which is a cheat really; what were Paramount playing at here? Very fine combining of paintings with model work and well chosen angles create the illusion of the sleek-looking rocket ship and its roller coaster-like runway combined with an inverted ski jump set up; a lot of care was obviously taken to make these shots look as best as they possibly could. And at times there’s certainly an attempt at showing how believably people will react to things, like one half of a briefly shown couple choosing to stay behind because her other half wasn’t picked to leave, not to mention Stanton just wanting to save his own skin and not caring about anything else, but for the most part a rather cloying optimism dominates here. We expect and want some self-sacrifice, but the dignity displayed becomes unbelievable. During the lottery for the Ark’s limited seating of forty, not one of the young engineers and scientists objects when Hendron arbitrarily reserves space for his daughter, her boyfriend, a kid rescued from a rooftop and a stray dog! He even allows yet another lottery loser to join the line for the Ark so she can join with her boyfriend. No wonder the losers, who are presented as ungrateful ignoramuses, are rioting! The main characters don’t seem to even feel much distress, and we almost cringe when Randall becomes deeply upset when he’s chosen to go but deems himself undeserving of this.

The idea of selecting an equal number of men and women isn’t the most sensible if you think about it, and of course there’s the fact that they’re all white; I’m not into modern “woke” over-representation of minorities but come on, even for 1952 the odd non-white face could and should have been seen! The religious aspect reaches absurd heights [or lows] when the wheelchair-bound Stanton briefly walks, while even the interior of the Ark looks like a flipping church. One wonders why a priest wasn’t aboard. Yet it’s hard not to become emotionally invested in the whole thing, and there are moments which do uplift, like the resolving of the love triangle. Rush is delightful as Joyce right from when she slightly flirts with Randall upon meeting him just by the way she looks at him, and John Hoyt is terrific as Stanton, giving the character some humanity, making us understand his views. After all, wouldn’t many of us just think of ourselves if disaster was impeding? If you’re English, remember what I call the Great Zombie Loo Roll Epidemic of 2020, when people went mad buying things in shops, especially toilet roll, just before lockdown? For me, that showed what many of us are really like, so Pal’s film, to me, is nonsense in that regard. Yet of course I’m aware that I’m in 2023 talking about a film from 1952 when life was very different and it hadn’t been that long since the ending of World War 2 in which, for the most part, people did come together for the common good and Do What Was Right. When Worlds Collide remains a grand folly in some respects, but despite its very talky script it never slows down and, in these days of so many films being overlong, isn’t it great to have something so ambitious that’s still done and dusted in 85 minutes? It’s helped greatly by the musical score from Leith Stevens, which emphasises a feeling of grand tragedy throughout with its variations on a dirge-like theme. One can’t help but think of what could have been if Pal had been able to do what he wanted to do with it, but a peculiar resonance and likeable innocence remain.

Be the first to comment