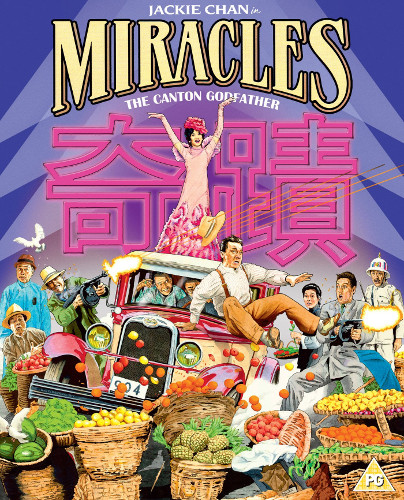

Miracles: The Canton Godfather (1989)

Directed by: Jackie Chan

Written by: Damon Runyon, Edward Tang, Hal Kanter, Harry Tugend, Robert Riskin

Starring: Ah-Lei Gua, Anita Mui, Jackie Chan, Lo Lieh

AKA QI MI, MR CANTON AND LADY ROSE, BLACK DRAGON

Hong Kong

RUNNING TIME: 128 mins/106 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

In the 1930’s, country boy Kuo Cheng-Wah is quickly cheated out of all his money when he arrives in Hong Kong. Madame Kao, a poor woman selling flowers on the street, persuades him to buy a red rose, saying it will bring him luck. His fortunes immediately take a dramatic turn when he renders assistance to a dying gang leader who unwittingly makes Kuo his successor. He tries to to find a different way to legitimately make a living for himself and his gang and opens a nightclub, but Fei feels that he should be leader, while Tiger, the leader of another gang, still wants a loan repaid that the dead guy owed him. Meanwhile Madame Kao learns that her daughter Belle, her wealthy fiancee and his father are all coming to visit, and she’s afraid that her poverty will bring disgrace to Belle. Kuo sets out to help by putting on an elaborate masquerade..…

It’s a strange premise for a story really. A charade is put on so that a woman’s fiancee and her fiancee’s father believe that her family is rich. What would happen if they visit the family again? Wouldn’t the same elaborate hoax have to carried out again, with a great many people asked to pretend to be others? Maybe A Pocketful Of Miracles, which Miracles: The Canton Godfather is partially based on and which I haven’t seen, gets around this? But then Jackie Chan’s favourite out of all his films, is a little strange itself; or at least it’s one Chan film I can’t entirely decide on. Technically it’s undoubtedly a triumph, the convincing sets, lavish costumes and graceful camera work really coming together to create a film that’s often great to look at and achieves the old Hollywood feel that Chan was aiming for, while the fight scenes boast the usual incredible choreography. And it’s clearly a heartfelt project too, with its theme of doing good deeds nicely put to the viewer. But, even though it tends to be much loved in books about Chan, I don’t think it entirely works. The pacing is really off, with pacy opening and closing sections which contain all the action book-ending an endlessly talky middle where things slow down to a halt – this is one Chan film where the short version works slightly better in my opinion, though I feel that some different cuts should have been made as it’s missing two important scenes that should have been left in. And the gangster part of the story and the “helping Belle” part of the story don’t always fit together that well – heck, even the fight scenes feel gratuitous. There’s still a lot to like though.

A Pocketful of Miracles was itself Frank Capra’s remake of his own Lady For A Day, which in turn was based on Madame La Gimp, a short story by Damon Runyon. It was screenwriter Edward Tang who showed A Pocketful of Miracles, one of his favourite films, to Chan who immediately wanted to partly remake it. Golden Harvest agreed to provide the budget required, on the proviso that it include some action. A huge set was built on the Shaw Brothers lot and half a mountain knocked down so shots from certain angles would look right. During production, a typhoon destroyed many of the sets and forced a rebuild, while Chan’s perfectionism held up proceedings. One shot alone took three days to set up. While performing a back flip over a rickshaw, Chan ended up with a piece of bamboo between his eye and eyebrow and a gash on his brow from a misdirected axe handle. Then a prop crew member fell off a building and production was closed down so Chan could see to the welfare of his family. The press spread the story that it was a stuntman who had died while carrying out a stunt, while there were rumours of the married Chan having an affair with co-star Anita Mui which Chan supposedly broke off in 1992. The film took nine months to shoot and ended up costing over nine million U.S. dollars, a staggering amount for a Hong Kong movie at the time. There was little chance of it making a profit even if it achieved good box office, which it did. The 22 minutes cut for the export version mainly removed scenes that didn’t advance the plot, while the Japanese version is roughly in between the other two cuts in length.

The camera zooming into a freeze frame of a ‘30s Hong Kong street is a nice opening, after which we see naive Kuo cheated out of his money by Tung, who pretends to be an employer recruiting people as long as they pay him a fee first. Nearby is a meeting between two gang bosses, one of them, Tiger, demanding that the other pay off a loan. It turns nasty and the guns come out, though in two later scenes bizarre reasons are given so that firearms are not employed. A car careens past Kuo and down some steps, after which he carries the wounded man to safety, though he dies anyway, though only after a moment which must only work for those who know Cantonese as “he carried me on his stomach” is mistaken for “give him”. Uncle Hoi suggests that new gang boss Kuo just do as he says, but Kuo, because he’s played by Jackie Chan, wants his organisation to go straight, something that doesn’t go down too well, while his insistence that he buy a rose every morning from the same seller also seems strange. He goes into partnership with singer Yang Luming to build and run a nightclub, leading to a terrific steadicam shot where the camera begins with an overhead view of Tiger as he leaves the Ritz, then sweeps left to a top view shot of Yang singing in front of her dancer. This is then followed by a glorious montage where Anita Mui, a major Hong Kong pop star, sings the same song in a series of stunning outfits inter-cut with typical gangster stuff like shooting attempts and exploding cars. For years I didn’t think that Kuo and Yang were supposed to be in a relationship because I only had the export cut. Seeing the Hong Kong version revealed that they were involved, in the first of the two scenes that shouldn’t have been cut, though it’s typically slapstick in nature and a door closes just as they’ve stopped accidentally injuring each other and are beginning to kiss.

Kuo of course has much else on his hands with Tiger demanding 50% ownership of the club, one of his men Fei wanting to be boss, and Inspector Ho’s habit of bursting in with his men to search everyone. And then Kuo, persuaded by Yang, decides to involve himself in something else – getting all these gangsters to pretend to be respectable officials so that the rose seller Madame Kao’s daughter Belle won’t disappoint her fiancee and his father on a visit, something that wouldn’t have been necessary if Madame Kao hadn’t pretended she was rich in her letters to Belle. One is soon left with the feeling that the first third is just a lengthy set-up for the main story as things slow down into an endless series of chatty though often humorous scenes where people are pretending to be other people while all the time more and more folk wind up kidnapped so the charade can continue. The longer version includes a subplot thankfully cut from the shorter one where Inspector Ho is trying to get money from Hung who’s pretending to be his uncle; it just drags things down further. Some tightening would have helped considerably around the middle, and when the action side of things is reintroduced it seems forced. The real climax of course hinges on whether Kuo and Yang’s plan to pretend that Madame Kuo has loads of “respectable” friends will come off. We are at least pretty involved at this point, especially in the second vital scene that shouldn’t have been cut from the export version when Kuo passionately begs a group of local dignitaries to help. Of course it’s ridiculous that they would ever consider doing such a thing, but the resolving of this issue, just after things seem lost, is genuinely heartwarming.

Familiar Hong Kong movie funny guy Richard Ng has some amusing Clouseau-type moments and the equally familiar Bill Tung is his typically deadpan self. In fact there are decent performances from recognisable Hong Kong movie faces all around, from Wu Ma as Hoi with a continual look of bemusement on his face, to Lo Lieh as another one of his imposing bad guys. Some of the comedy does work, like the gangsters and their ‘molls’ trying to be respectable folk is one especially funny bit – while of course any gangster violence and even threat is soft pedaled. There are four fights, which isn’t that many considering that this film is over two hours long. The first is early on when Kuo has to battle two guys to win his gang’s respect. Later on he descends some stairs in as Jackie Chan a way as possible [i.e. he barely uses the actual stairs], then after nearly an hour of no action at all hurls himself over and under rickshaws in a street brawl, and for the big finale is chased inside a rope factory by a gang led by second time Chan opponent Billy Chow where he uses every rope gag he could think of. In this film, anything that’s to hand is used from tables to cacti, his agility at age 44 is still astonishing, and sometimes so much cool stuff is done in just a few seconds that you want to rewind your disc to see if you missed anything. Appropriately considering this particular film, never have his fights seemed more like musical numbers, though it’s noticeable that Chan has less power in his fighting than ever before, and he holds back on performing daring stunts even if he still does things that you and I probably wouldn’t even attempt. The big brawl with Fei never happens, but then again this film is far more about doing good things than beating people up. Chan gives himself a scene where he asks the hoods he’s in charge of to do something they’ll be proud to tell their children rather than their usual criminal acts. His sincerity in expressing his belief that most people can do some good may seem naive but is something that one cannot help but like.

The cinematography is credited to familiar lenser Arthur Wong and five others, evidence of how complex this film was by Hong Kong standards. There are some great instances of steadicam work, such as when we move backwards and then to the side as Mui walks through some rooms in the nightclub. The song Rose Rose I Love You, which of course relates to the good luck roses Kuo keeps buying, makes for quite a catchy main theme, though I miss the amusing translation of the first subtitled copy of this film that I had with lines like “my love tentacles reach out to you”. There was a time when Hong Kong movie subtitles often used to be hilarious. Michael Lai provides some lively cues for the fight scenes and a sentimental theme for Madame Kao, though he rarely attempts to evoke the period. It’s interesting to speculate what might have happened if this film hadn’t been so darn expensive and had made loads of money. I wonder if Chan might have moved even further away from his usual kind of film and began to make movies where the action was increasingly less important – though that would have deprived us of some glorious stuff still to come. Miracles: The Canton Godfather remains a perhaps overly ambitious work that never quite balances all its elements right, and it’s always a film I want to like more than I do, but it’s certainly Chan’s most charming effort. Though he and Tang didn’t sort out all of its problems, you can tell that they wholeheartedly believed in this story, and by the end this belief does radiate off the screen so that you may be touched and may believe too – if only for a moment.

Be the first to comment