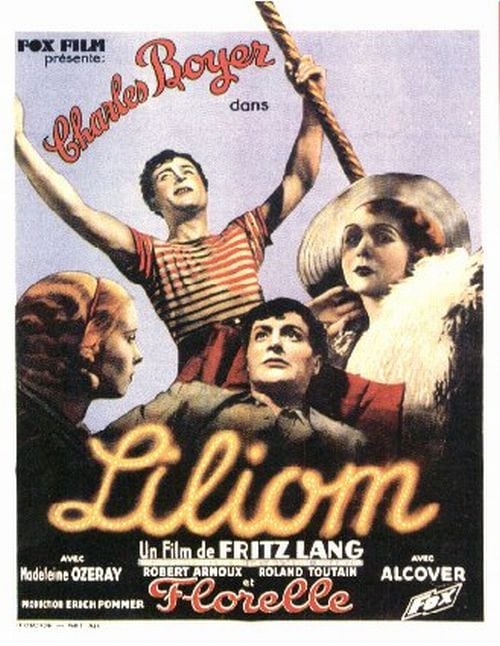

Directed by: Fritz Lang

Written by: Bernard Zimmer, Ferenc Molnár, Robert Liebmann

Starring: Charles Boyer, Madeleine Ozeray, Robert Arnoux, Roland Toutain

HCF REWIND NO. 197: LILIOM [France, 1934]

AVAILABLE ON DVD

RUNNING TIME: 118 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Liliom Zadowski is a barker at Madame Muscat’s carousel and also his boss’s lover. When a rival barker tries to get Liliom in trouble by telling the jealous Mme. Muscat that Liliom flirts with his customers behind her back, Mme. Muscat insults Liliom’s female customers Julie and Marie, Liliom comes to their defense, and Mme. Muscat fires Liliom. Liliom makes a date with Julie and Marie and leaves the carousel. Julie falls in love with Liliom and they move in together into a run-down trailer, but, while Julie works in a photo studio, Liliom just loafs, drinks and gets into violent arguments with Julie….

Despite writing for HCF, I do enjoy most types of films from time to time and dare I say it even enjoy a good weepie once in a while. Cinema Paradiso [director’s cut of course!], The Notebook and Carousel are three films [and there are others ] that never fail to reduce me to a blubbering wreck. It perhaps seems like a stupid exercise, though some may say that about being scared half to death as well. Carousel is a musical film from 1956. Aside from its wonderful music, its whimsical, yet actually quite dark, story deeply touched and haunted me from the very first time I saw it and always still does despite that bloody football team Liverpool’s hijacking of You’ll Never Walk Alone. I like to use Valentine’s Day as an excuse to review a film or two of a romantic nature which may otherwise seem out of place amidst all the horror, violence and weirdness that dominates HCF, so I’m going to talk about Liliom, which inspired Carousel, and actually this French film from 1934 does get distinctly weird after a while. Amazingly, this is the first time I had seen Liliom: I’m a sucker for comparing versions of a story, but when a version is almost as perfect as Carousel [I say almost: the film fell short of the original stage show somewhat, partly because of censorship], I guess I’ve been loath to bother with any other versions.

Liliom began life as a play in Hungary in 1909 by Ferenc Molnar, an English language version of which became very popular. A movie version was actually first planned in 1919 but was aborted: two later adaptations, the first entitled A Trip To Paradise, did get made and released in 1923 and 1930, the later still surviving though apparently not very good and basically just transplanting the two-act stage play. It is the 1934 version, directed by Fritz Lang [Metropolis, The Big Heat], which has overshadowed the others. It was made by the German director in France. Hitler wanted Lang to make films for him, and Lang promptly fled to America, though not before briefly stopping in France. One of the writers for this Liliom, Robert Leibmann, was also a fugitive from the Nazis after the company he worked for got rid of all their Jewish staff. Lang actually rewrote much of the script and spent 48 hours without sleep to finish editing the film. The French Catholic clergy protested Liliom on its initial release due to Lang’s conception of heaven to be too much against that of the church, while Molnar denounced it because he didn’t receive screen credit on the poster. The film was neither a critical nor commercial success, and the US release was shortened by 30 min, the full version going mostly unseen until 2004, though Lang often said it was his favourite amongst his work. Considering how close the musical is to it, to the point of sometimes copying exact dialogue, I would say that Rogers and Hammerstein certainly saw this film as well as the play before they wrote their musical play, which was first staged in 1945.

Now of course anyone familiar with Carousel first has to try to get its music out of their head whilst embarking on watching Liliom, but after a while it becomes easy to do. The title sequence may not have the Carousel Waltz, but visually it’s a far more interesting opening than the bland images of Henry King’s film, the titles appearing on what looks like glass as various images of circus and fairground happenings are flashed before us. We are hurled into the vibrant world that carousel barker Liliom is part of and really get a sense of it, most notably in what is probably the best carousel sequence I’ve ever, where Liliom sings and moves amongst the riders like a celebrity as the carousel spins round and round and all human life seems to be either on or around it. It’s a really joyous sequence that makes magical the perhaps tawdry and sleazy mileau it exists in. Liliom’s first sighting of Julie is also excellently done, Liliom always in mid-shot and surrounded by the goings-on occurring around him until he sees Julie and we finally get a close-up of him. The full-on sexuality seems really surprising in a film from 1934, but then French censors weren’t as uptight as US ones. When Liliom and Julie have a ‘date’ and sit on a bench, Liliom is all over her like a rash, even groping her breasts, though I couldn’t get over the moment a few scenes before where Liliom rows with his boss and lover Madame Muscat and says he’s never hit a woman except for one particular one, whom he put in hospital for three weeks! And this is the film’s hero? And Julie’s still interested in him?

After they have shacked up [no, they’re not even married!], what we are clearly seeing is a relationship which is of the sado-masochistic kind. We only see Liliom, who not only lazes around but gambles, possibly sleeps with a prostitute and refuses offers of jobs because, in Julie’s words, “he has an artistic temperament”, only hit Julie once, but it’s implied he does it a lot, and it’s quite painful to witness Julie’s blind love for this brute, especially when she has a rival for her affections in the form of a nice guy. Liliom can’t handle her goodness and reacts in the wrong ways, be it with violence or staying out constantly. Compared to Carousel, which softened matters, Liliom isn’t all that enjoyable to watch at times – you just want Julie to Get A Grip, but it’s possibly more true to its title character. Just over half way the film goes into fantasy and Liliom meets justice at the Pearly Gates, but he doesn’t actually seem to change much, which is maybe more believable: I’m not sure someone like Liliom, even if he has moments of clarity, would really change. Liliom is allowed to come back to earth for one day, but unlike Carousel’s Billy Bigelow, he doesn’t actually do any good at all. The ending is still a bit more positive than that of Molnar’s play, which is as nihilistic as they come, and I’m surprised it was changed, considering the gloomy fatalism of some of Lang’s other work, but then by now his film has become slightly comedic with things like its heavenly scales tipping the balance of Liliom’s fate.

Heaven in this movie seems to be a somewhat creepy echo of things on earth, at least the area where Liliom goes: we do see him go past lots of cherubs with wings which are so obviously paintings but impressive nonetheless. Either way, it’s far more interesting than Carousel’s plastic stars. Certain things seem to have seeped into later films which depicted the Afterlife like A Matter Of Life And Death and Orphee: there’s even a bit where Liliom has to watch a visual recording of himself just like in the 1984 Defending Your Life. The totally stage-bound film does drag in a few places and the final section seems a bit truncated. The two central performances are simply stunning to watch though. Charles Boyer, before he was typecast as a kind of American housewife’s fantasy of a mysterious, suave European lover, is wonderfully exuberant and you just can’t take your eyes of him, while Madeleine Ozeray is really touching and convincingly pathetic in her role. A couple of times, I just wanted to slap her character before I realised how wrong that was. Is Julie’s love for Liliom really beautiful or just pitiful? The film asks us to make up our minds. The controversial line in all version of this tale that understandably winds many women up about hits not hurting seems to me, at least in this version, saying how illogical love can be rather than condoning domestic abuse.

Liliom makes effective use of its score, an early effort by Franz Waxman who became a major Hollywood composer after James Whale saw Liliom and thought Waxman would be a good choice for scoring Bride Of Frankenstein. There’s no score for the first half, but when Liliom goes to heaven and afterwards the music plays almost constantly. It sometimes sounds genuinely otherworldly. Having finally seen it, I don’t think that I’ll be returning to Liliom as often as Carousel with its cosier sentimentality. It’s at times a quite remarkable picture that makes many Hollywood films of the time look stiff and awkward, but it’s also a very harsh and, despite its whimsical elements, rather honest film that depicts a situation in which far too many women still live their lives in as well as the craziness that love can sometimes be. It’s uncomfortable and to some even inexplicable, but sometimes love is like that.

Rating:

Be the first to comment