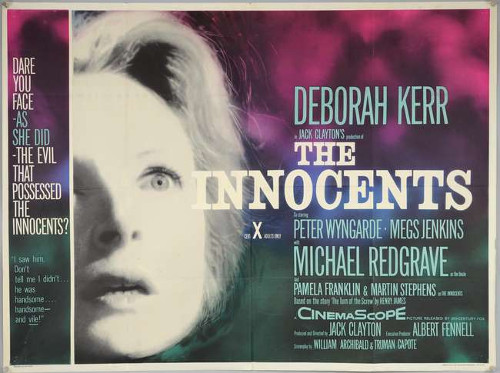

The Innocents (1961)

Directed by: Jack Clayton

Written by: Henry James, John Mortimer, Truman Capote, William Archibald

Starring: Deborah Kerr, Martin Stephens, Pamela Franklin, Peter Wyngarde

USA

AVAILABLE ON DVD

RUNNING TIME: 100 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

SPOILERS

In Victorian England, the uncle of orphaned niece Flora and nephew Miles hires the inexperience Miss Giddens as governess to raise the children at his country estate with total independence and authority. She meets the housekeeper Mrs Grose, and Flora, who seems to be a lovely young girl. Then Miles arrives having been expelled from school for mysterious reasons, and Miss Giddens starts to see brief glimpses of a man and a woman in and around the house. Could they be the former governess Miss Jessel and valet Peter Quint, even though they are supposedly dead?….

Most film fans, especially horror fans, have one film which once terrified then senseless. I’ve seen quite a few films which have frightened me, but none so much as The Innocents. I first saw it about twenty years ago late at night, and was absolutely terrified, to the point where I had to stop it [luckily it was a video copy of a TV showing a few nights before]. Only about twelve years after did I venture to watch it again, and it was still scary, though nothing can match that first viewing, and I was more appreciative of a what a truly brilliant film it is, so cleverly crafted from beginning to end. It’s an adaptation of Henry James’ novella The Turn Of The Screw, one of the all time great ghost stories. It’s a story which has been filmed quite a few times, though usually for TV, and I’ve seen two other versions. They also are a bit frightening – you’d have to be Uwe Boll to screw this tale ut – but Jack Clayton’s film is the best version, in that it’s fairly faithful to its source whilst tweaking it and never forgetting that it’s also a film. The script by Truman Capote and William Archibald is an object lesson in how to adapt a story for the screen, not deviating much but adding detail that works in both a visual sense and a psychological sense. It’s also, of course, the scariest.

It’s all about subtlety. There are no sudden jumps, but tons and tons of unsettling detail. The glimpses of the ghosts are almost matter of fact but more effective for that very reason. Cameraman Freddie Francis’s use of widescreen is crucial here – you’re forever on edge looking at the sides of the frame even more than the centre, which is often bathed in really bright light – indeed, this is a really bright film [they actually had some trees painted to make them brighter], and we are just as on edge during scenes in the middle of the day as we are during night time scenes. Despite the fact that Clayton himself was disappointed with the way that the appearances of Quint were handled, considering them too obvious, Quint’s face appearing out of the dark outside a window is very unsettling [and was copied by Mario Bava for his superb The Whip And The Body], but the bits which really got me, in fact they scared the living shit out of me, are the shots of Miss Jessel, clad in black and with a face you can’t quite make out, sitting on reeds on the other side of a river. I was haunted by that image for years. More frightening in an even more understated way are some of the scenes with the children, who may or may not be at times possessed by the ghostly pair. There’s a really eerie early scene where Flora is standing at the end of Miss Giddens’s bed looking both angelic and creepy at the same time, and another bit where Miles plants a big kiss on Miss Giddens’s lips which is both creepy and perverse [and bothered the studio 20th Century Fox who wanted it removed]. Interestingly, there’s one scary bit that was unintended – you briefly see ‘something’, but it’s actually the clapperboard which they’d left in the shot! Clayton decided to leave it for its unsettling effect.

Despite being on the face of it a very subtle film, it actually has very disturbing elements to it. Aside from the fact that this is another one of those films [and many of the great horror films have this] where the ghosts may just be in Miss Giddens’s head, she’s actually going mad, and ends up being a child murderer, there’s also a really nasty element of sexual perversion in the film. It’s very [and I mean very, after all this was 1961] subtly stated, but it becomes apparent that Quint and Miss Jessel indulged in a sado-masochistic relationship and that the children not only may have witnessed some of this but were drawn into it somehow. There are other elements which are only half-stated but add to both the unease and the fascination, such as the children hurting animals. Things such as flowers and statues are used throughout for symbolism, some of it obvious stuff such as the loss of innocence etc, but it’s incredible the amount of thought that went into every scene and setting. The exterior scenes were all filmed at Sheffield Park House, but inside everything is a carefully thought through set.

The film’s dreamlike feel is reinforced by having every scene change [bar one] be through a dissolve, so often for a split section you have a really unsettling composition of two scenes together at the same time. Clayton was supposedly disappointed with George Auric’s score but it works well, as does the haunting children’s song sung throughout by various characters, being more subtle than the usual horror score, yet still making its own contribution to the terror, such as the eerie high-pitched electronic sound you sometimes hear just before a ghost appears. Deborah Kerr claimed her performance in this was her best ever and I can’t argue with that. She basically had to play both a character who was seeing ghosts and a character who was imagining the ghosts at the same time, to keep things ambiguous. Martin Stephens and Pamela Franklin really sell the idea of Miles and Flora being both typical children and maybe being evil and possessed [apparently they weren’t told of the story’s darker elements]. Cary Grant wanted to play the uncle at the start of the film but wished to appear at the end as well as the start, so in the end Michael Redgrave did the role. There is one odd shot right at the end taken from Quint’s point of view, and I’m not sure it works though there must have been a reason for it, but from acting to sound design to photography to dialogue – you name it – I can’t think of a single aspect of this movie which could be improved and believe it is probably the greatest ghost story [unless you count Vertigo] on film.

Be the first to comment