Terry Gilliam is one of my favourite film-makers, but while he has many fans and many of his films have been studio productions and have made money [not to mention the fact that stars can’t wait to work with him], he still has the reputation as a maverick, a guy working outside the system whose visions can never really be taken to heart by either Hollywood or the paying public. In some ways I think he’s like Tim Burton, but in that case why is it that Burton’s style has found mass appeal, to the point that it’s virtually a brand, and Gilliam’s hasn’t? Perhaps it’s because a Gilliam film will often combine great sophistication with extreme silliness, it’s definitely the films of his that reigned in this tendency that were the most commercially successful. One thing I think is certain though – if the definition of an auteur is, as many have claimed, someone who basically makes the same film over and over again [something Alfred Hitchcock said about himself], then Terry Gilliam can almost be the perfect example of the term, aside from the fact that you can normally tell a Gilliam film within minutes by the way it is shot, with constant use of wide angle lenses. Many people go on about his astounding visual imagination, which, unusually amongst film directors, seems to be more influenced more by painters like Gustav Dore and Pieter Brueghel than other films, and I think that few other directors are as good at dream imagery, but thematically his films are fascinating too.

Despite their fantastical settings, all his films seem to me to be quite personal [though obviously some more than others]. Most of his films feature characters who escape from reality, so perhaps these people could be substitutes for Gilliam himself, and all of his films could be said to be about liberty, while the world of every Gilliam film is a grotesque one, populated by folk who look and act strangely but are oddly believable. There’s usually a great deal of silliness, with the ghost of Monty Python [of whom he was of course a member, but played mostly bit parts and spent most of the time doing the cartoons] never having left Gilliam. In fact, you could probably say that if you like one, then you’ll probably like the other. Other recurring thematic and visual motifs you often find in his movies include a distrust of progress and technology, one man against the system, scatology, storytelling, dwarves and decapitations. Freud would have a field day with Gilliam, who quite plainly films whatever pops into his head, but I’m not going to get all intellectual here, after all I find Gilliam’s movies immense fun as much as anything else. Nor am I going to pretend his films are perfect, because quite often they are badly paced and messy, as if Gilliam likes to write down, produce and print everything his mind gives him there and then before he loses it. Sometimes they can be ‘too much’, as if he can’t bear to leave anything from his current stream-of-consciousness out. Nonetheless, I believe his films to be one of the greatest bodies of work by a director alive today, and in going through the movies he made, I hope to show why.

Gilliam was born on November 2, 1940 in Medicine Lake, a small town on the outskirts of Minneapolis, Minnesota, though in 1952 the family moved to Panorama in the San Fernando Valley, which funnily enough is the place on the other side of the famous Hollywood sign. At college he studied Physics, Art and Political Science and got straight ‘A’s, but was also editing a humorous college rag called Fang. In 1962 he walked into the offices of Help, a satirical magazine which had been the inspiration for Fang, and immediately got a job, working for Help for three years. Amongst other things he was in charge of the comic strips, which often featured photographs as opposed to drawings. When the magazine folded three years later, Gilliam became a freelance cartoonist for a while, developing a talent for drawing, then in 1967 left America for England, where he quickly found employment working for the BBC, doing animation for programmes such as Do Not Adjust Your Set. In the process he developed a quick, cheap and easy way to animate, interweaving images from photographs and paintings with his own pictures using an airbrush. Monty Python’s Flying Circus would then use Gilliam’s funny, surreal and sometimes vicious cartoons to link sketches together, and define the group’s visual language in things such as title sequences for their films and covers for albums. Gilliam though was initially just credited as ‘animator’ until he started appearing more, though always in tiny roles. Even now, one usually thinks of John Cleese, Graham Chapman, Terry Jones, Eric Idle and Michael Palin….and then Terry Gilliam. It’s hard to gauge the impact the series had today, with its stream-of-consciousness flow, its lack of punchlines and its total surrealism, but it remains one of the most important comedy programmes ever produced.

King Arthur, accompanied by his squire Patsy, is enlisting knights to join them at the Round Table, but upon reaching Camelot, he decides not to enter as it’s a ‘silly place’. God appears and instructs Arthur to find the Holy Grail, so he and his knights set out on a dangerous quest to find the Holy cup……….

Fans differ as to which is the best Monty Python movie, with I think a slight majority erring on the side of Life Of Brian, but personally I consider Holy Grail their best. There are some who don’t consider it a ‘proper’ Gilliam film, since he co-directed it with Eric Idle [who, along with the others, got irritated with Gilliam spending time on getting good shots!], and it doesn’t really have a narrative at all. It’s just a non-stop series of hilarious sketches which only occasionally don’t work, and which have become the stuff of comic legend, such as the Knights Who Say Ni, the French Taunters, the KillerRabbit [who “has a vicious streak a mile wide”], the Holy Hand Grenade and the Black Knight who won’t surrender even with all his limbs chopped off. My two favourites though are Sir Lancelot slaughtering folk at a wedding reception when he think’s he’s rescuing a damsel in distress [“I just get carried away”], and the two guards told to guard the prince who get their instructions confused, which brilliantly showcases Python’s not-remarked-on-enough verbal genius, though it’s their surreal craziness, jokey sadism and occasional social comment which are in full flight in this movie.

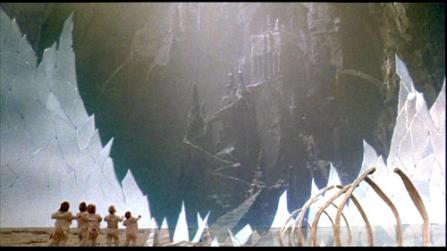

Sometimes making a virtue of its tiny budget, such as the people clicking coconut shells together because they couldn’t afford horses, for me the movie only really falters in its modern day ending, where it seems they really didn’t know how to end the film. In terms of direction it’s often clumsy and very much a ‘starting out’ movie, but already Gilliam works in some unusual angles and the occasional stunning shot, such as a ship coming out of the fog and knights looking like they are emerging from a giant skull. Despite its silliness, the film has a rather convincing feel for its period, its constant mud and fog seeming more realistic than the gloss of most Medieval-set films. A true comedy classic then, which justifiably was a big hit, and it would be followed by two more Python movies, Life Of Brian and Monty Python’s The Meaning Of Life, both of which Terry Jones directed alone, though Gilliam did make a lengthy prologue to the latter film, The Crimson Permanent Insurance, a crazy tale of aged accountants rising up against their oppressors, featuring imagery which fore showed Brazil.

A ferocious monster called the Jabberwock is terrorising the kingdom. Meanwhile after the death of his father, Dennis Cooper, a young cooper, leaves his village and his sweetheart to seek his fortune in the big city, but finds himself very unwelcome and becomes embroiled in the affairs of King Bruno The Questionable, who is looking for a champion to destroy the Jabberwock.

Jabberwocky is another Medieval-set adventure and in many ways it comes across as another Monty Python film, albeit without all the Pythons, though Michael Palin is the star and two others make cameo appearances. Gilliam doesn’t seem too fond of the film, sometimes claiming that his next movie Time Bandits is the first ‘true’ Gilliam movie, but I think he does Jabberwocky an injustice, because it really is an entertaining watch that at times is as funny as any Python film. It does have slightly more of a narrative than Holy Grail, though only slightly, but Gilliam took advantage of the opportunity to create an even more convincing Medieval world second time round. Mud, grime and shit is everywhere, while buildings constantly seem on the verge of collapsing, with the inside of King Bruno’s palace constantly suffering from falling dust and even masonry, as well as being too dark to really see much. Of course this is usually played for laughs, my favourite example being Bruno pointing out to his daughter the tower in which he ‘s going to make her a bridal suite….only for it to fall down. The film is even gorier than its predecessor, but again, it’s usually done for comedic effect, with one guy hiding under a bed crushed to death by romping lovers who cause the bed to break, and the brilliant sequence where for ten or so minutes we stay on a shot of Bruno, his daughter and his advisor watching a tournament while they are being spattered with more and more blood.

For me though, the funniest scenes involve Bruno [a brilliant performance by Max Wall in a film full of British comedy talent] who appears to wear a bonnet and a nappy, and his incompetent assistants, and they have me in hysterics every time I watch the film. Critics of the time couldn’t understand how a film could be so silly and crude [there’s the ultimate in shit jokes] but attain to some kind of seriousness by being visually stunning, with this time Gilliam cramming the film with painterly shots. They totally missed that at times the script, co-written by Charles Alverson, is actually quite sophisticated in places, with fairy tales and the idea of fairy tales being subverted, for example with the character of Princess Rita who is so stoned out of her mind on fairy tales that you don’t want to see anyone disillusion her, and the ending where Dennis doesn’t end up with the woman he wants to end up with. The actual Jabberwock is only seen towards the end but it’s well worth the wait, a truly hideous creature based on an old wood carving that works superbly despite being obviously made with very little money. Jabberwocky, which failed at the box office, shows evidence of carelessness in places and suffers especially from a poor score comprised mainly of badly recorded classical music such as Modest Musssorgsky’s A Night On Bare Mountain, but it’s a film that never fails to crease me up and is rather more intelligent than it at first seems.

For me though, the funniest scenes involve Bruno [a brilliant performance by Max Wall in a film full of British comedy talent] who appears to wear a bonnet and a nappy, and his incompetent assistants, and they have me in hysterics every time I watch the film. Critics of the time couldn’t understand how a film could be so silly and crude [there’s the ultimate in shit jokes] but attain to some kind of seriousness by being visually stunning, with this time Gilliam cramming the film with painterly shots. They totally missed that at times the script, co-written by Charles Alverson, is actually quite sophisticated in places, with fairy tales and the idea of fairy tales being subverted, for example with the character of Princess Rita who is so stoned out of her mind on fairy tales that you don’t want to see anyone disillusion her, and the ending where Dennis doesn’t end up with the woman he wants to end up with. The actual Jabberwock is only seen towards the end but it’s well worth the wait, a truly hideous creature based on an old wood carving that works superbly despite being obviously made with very little money. Jabberwocky, which failed at the box office, shows evidence of carelessness in places and suffers especially from a poor score comprised mainly of badly recorded classical music such as Modest Musssorgsky’s A Night On Bare Mountain, but it’s a film that never fails to crease me up and is rather more intelligent than it at first seems.

Kevin is an 11 year old boy fascinated by myths and legends and neglected by his parents. When six dwarves fall from another dimension into his bedroom, Kevin can’t wait to join them on their adventure. These miscreants have stolen a map from the Supreme Being showing all the ‘time holes’ in the Universe and intend to jump from period to period robbing………

Time Bandits sees Gilliam, after the commercial disappointment of Jabberwocky, going for a somewhat more ‘commercial’ kind of film [though with better marketing I reckon the Python-style Jabberwocky could have actually done very well indeed], and it remains the Gilliam film most aimed at children. That’s not to say it’s a bland and ‘safe’ movie though, far from it! The film is definitely fun from start to finish, with the idea of a group of people jumping from time to time often just an excuse for plenty of humorous sequences. With Python a strong influence again, this allows for some wonderful character portrayals such as John Cleese as an effete, mincing Robin Hood and Ian Holm as a Napoleon obssessed about his small stature. Despite some striking special effects moments done on a small budget, such as a giant carrying a ship, Gilliam doesn’t feel the need to cram the film with action scenes, but the sense of wonder and sheer imagination on display mean that even if released today, I reckon the film would be popular with many kids. I say ‘many kids’, not ‘kids’ in general, because this film has quite possibly the darkest ending of any movie geared towards children. You could say that the people involved ‘had it coming’, and I admire Gilliam’s gall, but for once I’m never entirely sure whether he made the right decision.

Then again, maybe it fits in with the general themes of Time Bandits. Kevin may be having the time of his life, but all his ‘heroes’ end up beng disappointments, and even the Supreme Being [obviously God, a fantastic walk-on part by Ralph Richardson who, in keeping with Gilliam’s fondness for improvisation, changed most of his lines] doesn’t seem very competent. Kevin’s fantasy adventures may prepare him for the real terror of real life, but dreadful events could still be just around the corner. Gilliam and his co-writer Michael Palin also offer pointed jabs at lazy consumerist parents and bureaucracy, both of which help ensure that the film doesn’t really date. Its low budget only really shows in the climax, where folk from various times and places do battle with Evil [another great villain from David Warner, replete with H.R.Giger-like stuff on his head and with some of the freakiest looking henchthings you could imagine]. Time Bandits was a huge hit and Gilliam was immediately asked to make a sequel. Gilliam though, wanted to get a project off the ground that he had started work on beforehand.

Then again, maybe it fits in with the general themes of Time Bandits. Kevin may be having the time of his life, but all his ‘heroes’ end up beng disappointments, and even the Supreme Being [obviously God, a fantastic walk-on part by Ralph Richardson who, in keeping with Gilliam’s fondness for improvisation, changed most of his lines] doesn’t seem very competent. Kevin’s fantasy adventures may prepare him for the real terror of real life, but dreadful events could still be just around the corner. Gilliam and his co-writer Michael Palin also offer pointed jabs at lazy consumerist parents and bureaucracy, both of which help ensure that the film doesn’t really date. Its low budget only really shows in the climax, where folk from various times and places do battle with Evil [another great villain from David Warner, replete with H.R.Giger-like stuff on his head and with some of the freakiest looking henchthings you could imagine]. Time Bandits was a huge hit and Gilliam was immediately asked to make a sequel. Gilliam though, wanted to get a project off the ground that he had started work on beforehand.

Sam Lowry is a worker with no ambitions in a future society controlled by convoluted and ineffecient bureaucracy, but in his dreams he is a winged knight who battles the forces of darkness for the love of a fair maiden. When he tries to right a wrongful arrest, he comes face to face with a lady who is the spitting image of the woman of his dreams, but she may be a terrorist………

Sam Lowry is a worker with no ambitions in a future society controlled by convoluted and ineffecient bureaucracy, but in his dreams he is a winged knight who battles the forces of darkness for the love of a fair maiden. When he tries to right a wrongful arrest, he comes face to face with a lady who is the spitting image of the woman of his dreams, but she may be a terrorist………

In my opinion Brazil is Gilliam’s masterpiece and, although he would go on to make some terrific films afterwards, I don’t think he’s ever quite topped it. I personally consider it one of the greatest films ever made, an incredible work of cinematic art,and it almost feels like its creator was worried he may never make another film again so went totally for broke. It’s one of those films where every scene and every shot contains something interesting, and you notice more and more with each viewing. Some say the film has too much in it, but when we are drowned in dull blockbusters which rehash the same ideas and images over and over again, we should treasure a film that has too many ideas, too many themes, etc. Like many of the great films, it has influences, ranging here from Blade Runner to Vertigo, and seems in part to be a variation on George Orwell’s 1984, which had of course been filmed the year before, but is also a film like no other. It’s partly a scathing indictment of bureaucracy, set in a near future world which is dominated by machinery which constantly breaks down, and paperwork, which in one audacious scene is seen to actually suffocate someone, freedom destroyed by bureaucracy you could say. Considering the idiocy which is seemingly everywhere today, especially in this country, Brazil was incredibly prophetic in this respect, but the film also mocks many other things which have increased since the film’s release, such as the obsession with looking young. Gilliam still makes many of his points with humour, but here it’s of an even blacker kind than before, like the plastic surgery which basically destroys someone’s face, or the people having to pay for their own torture. There’s less of Python here, but it’s still present in places, I mean there are people literally suffocated by shit. Despite its surreal elements, the future presented by Brazil, as grim and nightmarish as it might be, is an all too plausible and relatable one, and interestingly makes us dislike it so much that we are willing to accept a terrorist as a potential hero. In fact Robert De Niro’s Harry Tuttle is more of a hero than Jonathan Price’s Sam Lowry, who only decides to actually fight the system when it’s too late.

Of course Sam does retreat periodically to his dreams, which are some of the most stunning dream sequences ever filmed and rife with Freudian imagery, as dreams often are, from gigantic pillars bursting out of the beautiful green countryside ground to a huge samurai. Again, the budget for Brazil was not very big, and Gilliam had to give up on some of the sequences he wanted to do, but the effects are astounding, with the scenes of Sam flying some of the most graceful ever filmed. For the first time, Gilliam is able to indulge his considerable but not often mentioned romanticism with the love story in the movie, and this climaxes with some really Freudian, not to mention actually Oedipal, stuff which is breathtaking in its audacity. Then, at the finale of a film which is leisurely paced for the first two thirds and then goes berserk for the final third, there’s that ending, which I don’t find as grim as many do – after all, he escapes. Michael Kamen’s score for Brazil is astounding, brilliantly incorporating Arry Borosso’s escapist Depression Era song ‘ Brazil’ whilst giving all of Gilliam’s visuals and sequences musical backing to match. The ending, amongst other things, was a source of controversy when head of Universal, Sidney Sheinberg wouldn’t release the film unless severe alterations were made, and created his own dreadful version of the film, replete with happy ending, though it wound up only being show on US TV. Eventually Gilliam put an ad in Variety asking Sheinberg when he was going to release his film, and Sheinberg finally gave in, though this version was thirteen minutes shorter than the original cut. What isn’t widely known is that, although the full version is widely available these days, the US ‘uncut version’ and the UK ‘uncut version’ actually have slight differences including different openings.

Of course Sam does retreat periodically to his dreams, which are some of the most stunning dream sequences ever filmed and rife with Freudian imagery, as dreams often are, from gigantic pillars bursting out of the beautiful green countryside ground to a huge samurai. Again, the budget for Brazil was not very big, and Gilliam had to give up on some of the sequences he wanted to do, but the effects are astounding, with the scenes of Sam flying some of the most graceful ever filmed. For the first time, Gilliam is able to indulge his considerable but not often mentioned romanticism with the love story in the movie, and this climaxes with some really Freudian, not to mention actually Oedipal, stuff which is breathtaking in its audacity. Then, at the finale of a film which is leisurely paced for the first two thirds and then goes berserk for the final third, there’s that ending, which I don’t find as grim as many do – after all, he escapes. Michael Kamen’s score for Brazil is astounding, brilliantly incorporating Arry Borosso’s escapist Depression Era song ‘ Brazil’ whilst giving all of Gilliam’s visuals and sequences musical backing to match. The ending, amongst other things, was a source of controversy when head of Universal, Sidney Sheinberg wouldn’t release the film unless severe alterations were made, and created his own dreadful version of the film, replete with happy ending, though it wound up only being show on US TV. Eventually Gilliam put an ad in Variety asking Sheinberg when he was going to release his film, and Sheinberg finally gave in, though this version was thirteen minutes shorter than the original cut. What isn’t widely known is that, although the full version is widely available these days, the US ‘uncut version’ and the UK ‘uncut version’ actually have slight differences including different openings.

In the late 18th century, an unnamed European city is being beseiged by the Turks. Inside, a fanciful touring production of the fantastical adventures of the notorious Baron Munchausen is interrupted by the real Baron who blast its inaccuracies. Accompanied by a young girl called Polly, he sets out on a quest to save the city and find his lost assistants………

You might think that a director, after making something like Brazil and fighting a battle to get it released, would make a simple, straight-forward, unambitious film next. Not Gilliam! He went on to another elaborate fantasy movie, and though not quite the masterpiece of Brazil, it is perhaps more enjoyable as a straight-forward piece of entertainment. The actual Baron Munchausen was a real person who lived in the 1700s and who elaborated on his adventures, though the book immortalising his escapades, supposedly by Munchausen himself, was actually written by other hands. It had already formed the basis of a 1943 German film and a 1961 partly-animated movie before Gilliam made his version. Gilliam’s The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen is a stunningly imaginative and inventive movie in which one incredible idea and scene follow one another, at a pace which is almost too frantic – this is Gilliam’s fastest paced film and in fact he has said several times he wants to restore around ten minutes which he initially cut from the picture and in his opinion would allow it to breath a bit more. In some ways it’s like Time Bandits, with set pieces in a variety of fantastical locations, from a Turkish palace to the inside of a whale, from underground in the domain of Vulcan to the Moon, which are often comical in nature. Here though, the humour reaches surreal heights [or some might say depths!], like the sequences on the Moon where the King [a hilarious cameo from Robin Williams] and the Queen have detachable heads [in a film which is jammed with images of decapitation!]. Gilliam loves to indulge his actors and often allows them to improvise, which is why people usually love working with him, though it does tend to slow the pace of his films down a bit sometimes!

This may also be Gilliam’s brightest film, with the film packed with glorious colour, but that is not to say that darkness is absent from this movie, because it certainly isn’t, especially when the frightening sketetal and winged Grim Reaper appears. Gilliams shows a skill for over the top action, hinted at in Brazil, where Munchausen and his assistants, who all have special powers such as being able to run extremely fast and having super strength, battle the Turkish army [see the Baron riding on a cannonball!], but some of the best bits are quiet, like the dreamlike sequence of Munchausen travelling to and arriving at the Moon, with a beautiful shot of his balloon amongst the stars in space. Then there are the scenes with Uma Thurman’s Venus, a nice romantic diversion and based, like a great many of Gilliam’s visuals, on a painting. The sense of wonder in this film is truly incredible, while, despite it being less sophisticated on the surface than Brazil, there’s much sub-text on the position of and the need for stories. Some have said that this movie marks the end of a trilogy for Gilliam, with Time Bandits showing a boy needing to escape into a fantasy world in order to prepare himself for real life, Brazil showing an adult doing the same with less positive results, and The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen showing the fantasy world, or the world of the imagination, finally being the saviour of the adult as an old man and winning out over the Age Of Reason. The ending makes little sense narratively but it’s exceptionally rousing. Despite this movie being such uplifting fun, it was badly released by Columbia in revenge for the film going ridiculously over budget, something which was not entirely Gilliam’s fault. Of course the film was going to be a flop if it received limited distribution and hardly any publicity!

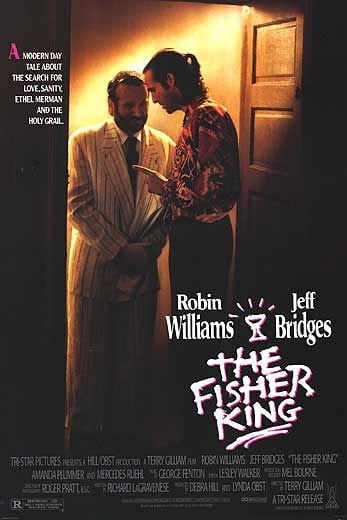

After his insensitive on-air comments inadvertently prompt a depressed caller to embark on a massacre, Jack, a cynical, arrogant radio host, becomes dejected by remorse. Three years later, he’s saved from suicide by Parry, a homeless man suferring from hallucinations and a desire to find the Holy Grail. He learns that three years ago Parry’s wife was one of the people killed by Jack’s murderous caller………

After his insensitive on-air comments inadvertently prompt a depressed caller to embark on a massacre, Jack, a cynical, arrogant radio host, becomes dejected by remorse. Three years later, he’s saved from suicide by Parry, a homeless man suferring from hallucinations and a desire to find the Holy Grail. He learns that three years ago Parry’s wife was one of the people killed by Jack’s murderous caller………

After The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen, Gilliam decided to ‘play the game’ for once and show Hollywood he could deliver a major studio movie that was commercial and rather more ‘normal’. For the first time in his career, he was willing to film a script he hadn’t written or co-written, but he was lucky in that Richard LaGraveness presented him with a script that not only contained things which constantly interested Gilliam such as madness vs sanity, fantasy vs reality and a Holy Grail, but had a central theme of redemption which was especially appropriate for him – after all, he was trying to redeem himself in Hollywood’s eyes. The Fisher King is much more down to earth and much more of a character piece than his previous movies, and makes the most out of two [well four, if you count Mercedes Ruehl and Amanda Plummer, who are also excellent] superb performances. Jeff Bridges is fantastic as Jack, a character who has to undergo several transformations in the course of the movie including devil-may-care, despair and joy, but Robin Williams as Parry matches him, amazingly detailed yet subtle in his depiction of madness and romantic love. This is the most purely romantic of all of Gilliam’s films, and can almost be called his Romantic Comedy, but few Rom Coms contain scenes of such lovely sweetness like when Parry and Lydia, the woman he is crazy about, finally make a connection when they both have trouble eating Chinese food, and isn’t Anne’s devotion to the often dislikeable Jack so incredibly touching?

In sticking to the script, Gilliam generally manages to curb his excesses, but does throw in images of a huge red fire-breathing knight as Parry’s major hallucination and indulges himself with a wonderful imaginary sequence in New York’s Grand Central Station, where everyone pairs up and starts dancing. The elements of the Holy Grail myth which inspired LaGraveness to write his screenplay are actually downplayed for a great deal of the time,with even the ‘finding’ of the Grail a very quick scene, but Gilliam finds new things in his filming of New York’s buildings, discovering unusual structures and odd angles, and in the process making the city look almost Medieval, or at least from another time, the perfect setting for a modern day fairytale. Though I personally don’t find The Fisher King as fascinating as Gilliam’s best films, it remains a terrific feel-good movie, the kind that really makes you think the world is a wonderful place, and it does this without sacrificing intelligence. It was a major success for the film-maker – he showed he was able to do a more mainstream movie without sacrificing quality and integrity, and it was a major box office success.

In sticking to the script, Gilliam generally manages to curb his excesses, but does throw in images of a huge red fire-breathing knight as Parry’s major hallucination and indulges himself with a wonderful imaginary sequence in New York’s Grand Central Station, where everyone pairs up and starts dancing. The elements of the Holy Grail myth which inspired LaGraveness to write his screenplay are actually downplayed for a great deal of the time,with even the ‘finding’ of the Grail a very quick scene, but Gilliam finds new things in his filming of New York’s buildings, discovering unusual structures and odd angles, and in the process making the city look almost Medieval, or at least from another time, the perfect setting for a modern day fairytale. Though I personally don’t find The Fisher King as fascinating as Gilliam’s best films, it remains a terrific feel-good movie, the kind that really makes you think the world is a wonderful place, and it does this without sacrificing intelligence. It was a major success for the film-maker – he showed he was able to do a more mainstream movie without sacrificing quality and integrity, and it was a major box office success.

The year 2035 – the human race lives underground because of a lethal virus that wiped out five million people in 1996. George Cole, a convict, is sent back in time to gather information about the origin of the virus, but is accidentally sent to 1990, six years earlier, and finds himself in a lunatic asylum………

The year 2035 – the human race lives underground because of a lethal virus that wiped out five million people in 1996. George Cole, a convict, is sent back in time to gather information about the origin of the virus, but is accidentally sent to 1990, six years earlier, and finds himself in a lunatic asylum………

Like The Fisher King, Twelve Monkeys sees Gilliam playing ball with Hollywood again, and again with no loss of quality in the end product. With such a brilliant script by David and Janet Peoples, loosely based on Chris Marker’s La Jetee, it’s hard to see any director screwing the movie up, but Gilliam creates a clever, haunting puzzle of a film that is totally compulsive and draws you in from the first minute. The complex time travel stuff has the potential to hurt your brain if you think about it too much, and is perhaps reminiscent of The Terminator, but this is no action movie. Instead, the script and direction concentrate on a plot filled with clues that slowly unravels, and also emphasise the traumatic results of time travel, with star Bruce Willis very effective at showing this, though for me this is Brad Pitt’s movie, this being the first film of his where I said to myself “he’s actually bloody good”. He gives a superb and entirely convincing portrayal of Jeff Goines, the supposed madman who suddenly finds a dangerous purpose to his life. Of course I must not forget Madeleine Stowe, who gives the best performance I’ve seen her give, adding subtle layers to her rather cliched ‘ love interest’ character and really looking like an archetypal Hitchcock blonde in some scenes.

This is Gilliam’s most sombre movie, with no real humour except maybe for the incompetence of Cole’s bosses who seem to have trouble sending him to the right time. Accordingly he shoots in very restrained colour pallets, sometimes a dull grey, often white, with little actual colour creeping in, showing in visual terms the psychological states of its two main characters. The future scenes, replete with tubes and odd machines, are slightly reminiscent of Brazil but in many ways this feels even less like a typical Gilliam film than The Fisher King. The slow motion climax though, where past, present and future all converge, is brilliantly staged, with every shot designed to have maximum impact. I love the the irony in the story [such as Cole actually being indirectly responsible for the virus] and the many things that are in the film but not gone into detail, for example the group of homeless people who may also be time travellers. The MPAA cut a few seconds from Cole killing someone [Gilliam was keen to show that maybe Bruce Willis killing people is not fun!] but the studio were pleased with the film. Once again the director had succeeded in creating a really good movie from someone else’s script, and which again was a box office success.

This is Gilliam’s most sombre movie, with no real humour except maybe for the incompetence of Cole’s bosses who seem to have trouble sending him to the right time. Accordingly he shoots in very restrained colour pallets, sometimes a dull grey, often white, with little actual colour creeping in, showing in visual terms the psychological states of its two main characters. The future scenes, replete with tubes and odd machines, are slightly reminiscent of Brazil but in many ways this feels even less like a typical Gilliam film than The Fisher King. The slow motion climax though, where past, present and future all converge, is brilliantly staged, with every shot designed to have maximum impact. I love the the irony in the story [such as Cole actually being indirectly responsible for the virus] and the many things that are in the film but not gone into detail, for example the group of homeless people who may also be time travellers. The MPAA cut a few seconds from Cole killing someone [Gilliam was keen to show that maybe Bruce Willis killing people is not fun!] but the studio were pleased with the film. Once again the director had succeeded in creating a really good movie from someone else’s script, and which again was a box office success.

Oddball journalist Raoul Duke and his lawyer Dr. Gonzo head for Las Vegas to cover a motorcycle race and to search for that undefinable thing known only as the ‘American dream’. To aid their undertaking, they bring with them almost every drug under the sun………

Hunter S.Thompson’s cult novel may seem like an odd choice for a film by Terry Gilliam, considering that the director has said on many occasions that he has had very little experience of drugs, and also that it deals with a time and place that is more immediate than any of his previous films [think about it, even The Fisher King, despite making good use of New York, could basically have been set almost anywhere]. Incredibly though, Gilliam turned out another great movie that is full of energy, invention and a real punk-like sense of danger. It has the attitude and vibrancy of the work of a young filmmaker, out to make a mark and shake things up, rather than something made by a fifty eight year old. Gilliam’s and Tony Grisoni’s screenplay manages to be amazingly close to something many said was unfilmable, and the film has a real sense of the America of the early 1970s, when the hippie movement had evaporated into disillusionment and the mass drug taking had not resulted in peace, love and a brave new world but exploitation, paranoia and anger. The story brilliantly sets two casualties of the counterculture movement and places them amidst the gaudy tackiness of Las Vegas, the ultimate symbol of the consumerist America they wanted to get rid of.

Surprisingly Gilliam, for the most part [there is one fantastic acid scene] doesn’t go in for elaborate fantasy sequences, choosing to convey the altered states of the characters with things like tilted angles, disjointed editing, garish colours, back projection and missing frames. Despite the fact that our protagonists are off their heads all the way through, the film certainly doesn’t glamourise drugs or come down in favour or them. Duke and Gonzo may have a bloody good time every now and again, but it doesn’t really lead to anything and there’s probably more bad than good, with Gonzo revealed to have a really nasty side which the drugs bring our from time to time, in scenes which have an uncomfortable realism about them and show, as with The Fisher King, that Gilliam could easily make a totally realistic movie if he wanted to. Johnny Depp, whose narration peppers the narrative, does a personable imitation of Thompson but Benecio Del Toro probably had the harder role of the corrupt lawyer with a dark side. The two stars improvised much of their dialogue, partly because the script was rushed because of a deadline. Now I’ve mentioned words like ‘story’ and ‘narrative’, but actually the movie doesn’t really have either of those things. I must admit that, on first viewing, I didn’t really warm to Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas, but I’ve grown to love it. Duke and Gonzo may not behave very intelligently, but their exploits are chronicled with a very clever eye, and you pick up on more and more things each time you watch them.

Surprisingly Gilliam, for the most part [there is one fantastic acid scene] doesn’t go in for elaborate fantasy sequences, choosing to convey the altered states of the characters with things like tilted angles, disjointed editing, garish colours, back projection and missing frames. Despite the fact that our protagonists are off their heads all the way through, the film certainly doesn’t glamourise drugs or come down in favour or them. Duke and Gonzo may have a bloody good time every now and again, but it doesn’t really lead to anything and there’s probably more bad than good, with Gonzo revealed to have a really nasty side which the drugs bring our from time to time, in scenes which have an uncomfortable realism about them and show, as with The Fisher King, that Gilliam could easily make a totally realistic movie if he wanted to. Johnny Depp, whose narration peppers the narrative, does a personable imitation of Thompson but Benecio Del Toro probably had the harder role of the corrupt lawyer with a dark side. The two stars improvised much of their dialogue, partly because the script was rushed because of a deadline. Now I’ve mentioned words like ‘story’ and ‘narrative’, but actually the movie doesn’t really have either of those things. I must admit that, on first viewing, I didn’t really warm to Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas, but I’ve grown to love it. Duke and Gonzo may not behave very intelligently, but their exploits are chronicled with a very clever eye, and you pick up on more and more things each time you watch them.

Folklore collectors and con artists Jake and Will Grimm travel from village to village pretending to pretect townsfolk from enchanted creatures and performing exorcisms. They are put to the test ,however, when they encounter a real magical curse with real magical beings, requiring genuine courage………

Folklore collectors and con artists Jake and Will Grimm travel from village to village pretending to pretect townsfolk from enchanted creatures and performing exorcisms. They are put to the test ,however, when they encounter a real magical curse with real magical beings, requiring genuine courage………

It was a gap of seven years between Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas and Gilliam’s next film because he spent much time trying to set up projects which failed. I could actually write a whole feature on Gilliam’s unmade films, because they are many and fascinating, from The Defective Detective [about a detective who, guess what, escapes into a fantasy world] to Theseus And The Minotaur to The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, whose aborted production was the subject of the documentary film Lost In La Mancha. The Brothers Grimm seems like Gilliam had to make something, but was not entirely focused on the project, despite it being a really troubled production, with Gilliam constantly battling Miramax [or maybe because it was troubled]. Don’t get me wrong, this is a really fun movie that has more invention than most other studio fantasy movies around the time, but it’s a really uneven picture, half a would-be summer ‘blockbuster’, half a bonkers Terry Gilliam film, and is possibly the first Gilliam movie to not actually be about something. That said, I find the movie’s randomness and silliness very appealing. For the first time since The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen, Monty Python-esque silliness returns in full force, be it the torture scene accompanied by string musicians playing, to the plethora of dodgy French [and one Italian] accents by the villains [yet everyone else speaks their normal way]. There are also some wonderful moments of pure Gilliam randomness, like the formation of a bizarre Gingerbread Man, and quite a bit of nightmarish surrealism, including a horse that breathes a cocoon that tangles up a little girl.

Ehren Krugers’ script was rewritten by Gilliam and Tony Grisoni, and it’s packed with allusions to various fairytales, from Hansel And Gretel to Little Red Riding Hood to Cinderella, but frankly it’s a bit of a mess, especially towards the end where it seems like reams of pages had been torn out. The romantic ‘love triangle’ is especially badly written and rather pointless. Still, stars Matt Damon and Heath Ledger [who swapped parts] have terrific chemistry, and Ledger is especially good as the seemingly weaker half of the two. Some of the locales are very well rendered and imagined, notably the forest, which really is the scary fairytale forest you know from every fairytale, but the special effects, which see Gilliam working with a large amount of CGI for the first time, vary a great deal in quality. Some look fine, and certainly allow Gilliam to put his imagined visuals on screen more easily, but some are really poor and look horribly rushed, for example the really shoddy werewolf. With a highly atmospheric and vivid score by Dario Marinelli which is probably the finest score for a Gilliam film after Michael Kamen’s superb work on Brazil and The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen, The Brothers Grimm feels like it could, and should, have been a masterpiece, but just falls very short due to several bad flaws. For the Gilliam fan there are many pleasures to be had though and I believe it had many features that should have enabled it to be a hit – sadly though, it wasn’t to be.

Ehren Krugers’ script was rewritten by Gilliam and Tony Grisoni, and it’s packed with allusions to various fairytales, from Hansel And Gretel to Little Red Riding Hood to Cinderella, but frankly it’s a bit of a mess, especially towards the end where it seems like reams of pages had been torn out. The romantic ‘love triangle’ is especially badly written and rather pointless. Still, stars Matt Damon and Heath Ledger [who swapped parts] have terrific chemistry, and Ledger is especially good as the seemingly weaker half of the two. Some of the locales are very well rendered and imagined, notably the forest, which really is the scary fairytale forest you know from every fairytale, but the special effects, which see Gilliam working with a large amount of CGI for the first time, vary a great deal in quality. Some look fine, and certainly allow Gilliam to put his imagined visuals on screen more easily, but some are really poor and look horribly rushed, for example the really shoddy werewolf. With a highly atmospheric and vivid score by Dario Marinelli which is probably the finest score for a Gilliam film after Michael Kamen’s superb work on Brazil and The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen, The Brothers Grimm feels like it could, and should, have been a masterpiece, but just falls very short due to several bad flaws. For the Gilliam fan there are many pleasures to be had though and I believe it had many features that should have enabled it to be a hit – sadly though, it wasn’t to be.

Pre-teen Jeliza-Rose lead a troubled life with drug addict parents. When mum O.D.’s, dad takes her to his mother’s country place, but soon he dies too. To cope, poor Jeliza-Rose starts to create her own fantasy world with her doll head finger puppets, but then two strange locals appear to make her life even stranger………

Pre-teen Jeliza-Rose lead a troubled life with drug addict parents. When mum O.D.’s, dad takes her to his mother’s country place, but soon he dies too. To cope, poor Jeliza-Rose starts to create her own fantasy world with her doll head finger puppets, but then two strange locals appear to make her life even stranger………

2005 was shaping up to be an exciting year if you were a Gilliam fan. Not only was The Brothers Grimm due to come out, but during the six months between its completion and its release, the film-maker found time to make a second film, the low budget Tideland. I had to travel to London to see it because it got a really limited release but I didn’t regret it. I think there’s little doubt that Tideland is Gilliam’s most difficult film, and even if you admire it greatly like me, it’s a bit hard to warm to, but I don’t think Gilliam made the film to automatically be liked. Like many great art house movies, he made it to be experienced, so that you’ll be thinking about it for days afterwards. Based on the novel of the same title by Mitch Cullin, and written by Gilliam again with Tony Grissoni, Tideland, as well as being a very twisted variation on Alice In Wonderland [if only Gilliam could make a version of that!] is a heartbreaking story of a child who, by various means, copes with an extremely tragic existence. Jeliza-Rose does what any Gilliam character would do when confronted with a horrible life – escape into a fantasy world, but the actual scenes depicting this are limited, with Gilliam choosing to focus on Jeliza-Rose herself, while Nicola Pecorino’s wonderfully toned cinematography makes the yellow cornfields and the decrepit house the perfect places for a child’s imagination to run riot. Much of the film consists of Jeliza-Rose playing with her doll heads and Dickens the mentally-challenged man she forms a friendship with, and many seem to find the film boring. I disagree; this may be Gilliam’s slowest film, but it’s gentle pace is essential to getting us inside the head of it’s heroine without elaborate visuals.

There was much controversy about the way Jeliza-Rose is confronted with various unsavoury elements of life including drug addiction, madness and the physical reality of death, and Gilliam even shows, without really commenting on, a relationship that borders on being paedophilia [not to mention a sordid back story of incest and definite child abuse], but there’s nothing that says a film-maker can’t show children experiencing these things, and their depiction is essential to illustrate Jeliza-Rose’s growth from a person who starts off numb and feeling almost nothing to someone who starts to become a more ‘normal’ human being. The ending is actually really positive and life-affirming, and reveals Tideland‘s closest cousin to be Time Bandits, where a child’s strange and often dangerous adventures prepare him/her for the real world. Gilliam has often lamented how sad it is that children these days read less and have less of an outlet for their imaginations. Now, whilst there are great turns from Jef Bridges, Janet McTeer and Brendan Fletcher in this movie, it really belongs to Jodie Ferland who gives quite simply gives one of the best performance by a child actor ever. Honestly, I’m not exaggurating; she’s unbelievably tragic, sweet, funny and totally believable. She deserved an Oscar, but of course was not even nominated, because Tideland was mostly treated like dirt by distributors and critics, who constantly moan how formulaic most films are but often pounce on a film if it’s too odd or provokes too much of a reaction. Don’t these narrow-minded fools realise that a film doesn’t have to be automatically liked to be worthy of appreciation? Here was an artist, with things to say, expressing himself with no holding back, and in my view the treatment of this movie was almost criminal.

Dr Parnassus runs a sideshow with his mind called the Imaginarium, where people’s dreams come true. However, he once made a deal with the Devil when he fell in love, trading his immortality for youth, and now the Devil wants his part of the bargain – his sixteen year old daugher Valentina. Parnassus convinces him that if he seduces five souls in the Imaginaruim, he can keep his daughter………

Writing the brief and extremely simplified synopsis to The Imaginarium Of Dr Parnassus was not too easy, because the story that Gilliam and Charles McKeown [his co-writer on Brazil and The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen] came up with is very convoluted and not always clear – I knew what was going on because I’d read lots about it, but I reckon many don’t until a second viewing. This flaw aside, this is an astoundingly imaginative and brave movie with an amazing concept which, under Gilliam, is exploited to its full. It could almost be called the Portable Gilliam, because it contains pretty much everything you would expect to find in a Gilliam film, in fact it seems like the film-maker is almost making a summation of his career. There are echoes of everything from Jabberwocky to The Fisher King, but they are mostly echoes rather than direct quotes. The only thing that Gilliam seems to hold back on is the darkness – yes, the Devil plays a major part in the movie, but there’s no real sense of fear, with the sequences in the Imaginarium avoiding the horrific and the scary. Still, these scenes show Gilliam’s invention at it’s peak – after all these years, he is still capable of coming up with imagery which somehow gets through to your subconscious and often remind us of dreams that we all have probably had at some time [though I doubt many of us have dreamed of police with fish-net stockings doing a dance!]. Ladders go up into the sky, huge steps made from rock go up a mountain, giant jellyfish carry an alcoholic into space, huge shoes and jewellery exist underwater but also seem like they are in the sky, a boat ride in an adyllic setting turns to ugliness in one panning camera movement – despite what some purists say, CGI is perfect for Gilliam, at least when it’s good and combined with good old modelwork and sets, as it is here. Is it churlish to say though that my favourite image of The Imaginarium Of Dr Parnassus is one of the first ones, with the stage opening up in the centre of London, a relic from another time bursting into our modern world?

Of course the film isn’t just set in the Imaginarium, with some of my favourite scenes taking place early on, where we just spend time with Parnassus and his troupe and get to know them. Typically for Gilliam, the film’s pacing is all over the place, this film shows what many might say are his flaws as a film-maker in spades, but this is as purely Gilliamesque as you can get, and at times, especially towards the end, where four people’s imaginations are creating things at the same time and basically doing battle, it approaches Brazil for sheer gall and intensity. You may not understand all that’s going on, but you just don’t want the parade of fantastic ideas and visuals to stop. Of course this was the film which Heath Ledger sadly died during production of, but Gilliam’s odd decision to have Johnny Depp, Jude Law fill in for him really works. Ledger gives a really multi- layered performance, especially hard since we don’t really know much about him, and Tom Waits is a perfect Devil, but I believe it’s Christopher Plummer who dominates, basically playing Gilliam himself, a teller of stories to whom people don’t always listen to. The final scene, of Parnassus selling toy Imaginarium theatre replicas on a steet corner, is incredibly touching and seems incredibly personal too, with maybe Gilliam realising that, at his age, he needs to slow down? Interestingly, this one did reasonable business in the States and the UK but was a huge hit in many other countries.

Of course the film isn’t just set in the Imaginarium, with some of my favourite scenes taking place early on, where we just spend time with Parnassus and his troupe and get to know them. Typically for Gilliam, the film’s pacing is all over the place, this film shows what many might say are his flaws as a film-maker in spades, but this is as purely Gilliamesque as you can get, and at times, especially towards the end, where four people’s imaginations are creating things at the same time and basically doing battle, it approaches Brazil for sheer gall and intensity. You may not understand all that’s going on, but you just don’t want the parade of fantastic ideas and visuals to stop. Of course this was the film which Heath Ledger sadly died during production of, but Gilliam’s odd decision to have Johnny Depp, Jude Law fill in for him really works. Ledger gives a really multi- layered performance, especially hard since we don’t really know much about him, and Tom Waits is a perfect Devil, but I believe it’s Christopher Plummer who dominates, basically playing Gilliam himself, a teller of stories to whom people don’t always listen to. The final scene, of Parnassus selling toy Imaginarium theatre replicas on a steet corner, is incredibly touching and seems incredibly personal too, with maybe Gilliam realising that, at his age, he needs to slow down? Interestingly, this one did reasonable business in the States and the UK but was a huge hit in many other countries.

Not that he seems to be slowing down at the moment. I don’t know what the future holds now for Gilliam, who at the time of writing is seventy one years old; he’s recently tried to get The Man Who Killed Don Quixote off the ground again, with little success, and is currently trying the same with another old project, The Defective Detective. The Imaginarium Of Dr Parnassus would be a great end to his film-making career, but of course I’d love for him to create one more masterpiece from his wonderful, fertile and crazy mind. Sadly Gilliam has found most of his projects hard to get off the ground and even release [even The Imaginarium Of Dr Parnassus was passed on by its first supposed American distributor], and I’m not convinced he would be willing to put himself through it all again. Still, he has created a unique body of work which manages to be extremely fantastical and ‘out there’, while also being very personal. Through all of his films, even the two he didn’t write, Gilliam seems to be analysing himself, the world, and even tracking his own story, that of a wonderful storyteller and visualist who constantly has to battle dark forces to hear himself heard. I will still be watching his films when I am seventy one, and even then I am sure even they will seem fresh and I will be discovering new things and insights from one of the greatest film directors of all time.

Brilliant feature there Doc. Seems I’m a bit hit and miss with Gilliam though I do think he’s a genius.

For instance, I’m no Monty Python fan, however I did enjoy his artwork in it and bits where Gilliam appears. I love Fear and Loathing (obviously) and what I’ve seen of The Fisher King I enjoyed. Brazil had good parts but overall, not a fan. I know one thing, I must see a few more of his films.

Thanks Bat, I really enjoyed writing it. It’s interesting what you say,most people I know either love Gilliam or hate him. If you do want to check out more of his stuff, I would maybe say possibly Tideland and Twelve Monkeys first, as they are less Pythonesque and possibly closer to Fear And Loathing?