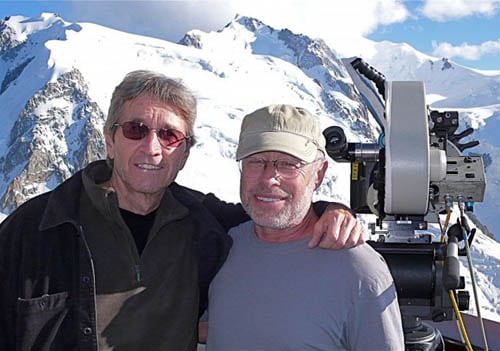

To celebrate the release of the mesmerising SAMSARA/BARAKA Blu-Ray Dual Play set released on Monday 14th January 2013, check out the Q+A with Ron Fricke (Director, Cinematographer, Co-Editor, Co-Writer), and Mark Magidson (Producer, Co-Editor, Co-Writer) below.

Had you always hoped to pick up where you left off with BARAKA?

Ron Fricke: Absolutely. It just took a while to get to the second film after Baraka.

Mark Magidson: It certainly wasn’t planned on. After I made Baraka I didn’t think, “oh I can’t wait to make the next one.” I felt both depleted but also complete. You have a sense that you’re never going to do something like that again and it takes time to recover. We went to 24 countries in three years— it was a crazy amount of travel. I made Chronos with Ron in 1985, and that was a 35-minute film that took us to 8 countries, which still took a tremendous effort. Doing these films really takes a big chunk of your life force, your life energy, and it takes a long time to be able to do that again—at least in my case. It’s very challenging to maintain any semblance of a normal life, or relationships. I have kids now. It’s challenging to undertake films like this that take that long, and making Samsara took even longer—almost 5 years. So it’s something that you have to make space for in your life. Everything in life is about choices, so it was one of those choices. I know Ron wanted to do it. I’d been through a lot from the time we made Baraka to when we started Samsara, and it was a time in my life when I could make the commitment to do it.

Ron Fricke: I came back to Mark and said it’s time to dust off your passport and get back out there. He was up for it. He was ready for another adventure out of the office.

What motivates you to make these unprecedentedly ambitious, technically and geographically complex, nonverbal widescreen epics?

Ron Fricke: I remember when I was a little kid I always looked at the theater as a temple. Looking at films in Cinerama, these big widescreen films, I hadn’t a clue what they were about but visually I was immensely moved by them. They gave me the sense that as viewers sit in the dark with their senses alert and defenses down, it’s a perfect opportunity to bypass their personalities and address their inner being. It all really happened with 2001: A Space Odyssey. When I was just a kid in college, it really whacked me in the head, and I guess I never got over it. The fact that you could take big screen, commercial cinema and do something so amazing without words. I’ve been drawn to that, and with Koyaanisqatsi [1982] I realized I was drawn to what I think of as a kind of guided meditation. Focusing on the sacred or transcendent. Some people think of it as self-indulgent but I think if it’s done carefully it can be a moving experience that’s neither sentimental or condescending. Mark has been drawn to it too. He understands the whole process. He could have gone out and made commercial movies, but this is some kind of art that really inspired him. Something really deep inside of him wanted to do something unique and meaningful.

Mark Magidson: I love that the films speak past individual languages and nationalities in a universal way, with just images and music that doesn’t need translating. I guess that sounds corny or something but I think on some level we want to feel a deep connection to each other and the life experience beyond those barriers.

What were your initial discussions like? Did you sketch out a plan for what you wanted to achieve and where you wanted to go? How did you approach SAMSARA differently than you approached BARAKA?

Ron Fricke: We did have a scenario for Samsara. It had a beginning, middle and end, and we knew we wanted to go to certain places. It was a guided meditation on the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. You could say that it’s sculpted by the power of flow—on a global level.

Mark Magidson: With Baraka we had a fairly elaborate written treatment, but we departed a lot from what was written. So having had that experience, there was some sense of confidence that we would be able to make a film that worked from the material. In this kind of filmmaking it’s the reality of the imagery that you bring back that you make the film with rather than whatever you’ve written, and some of the best visual connections you can make in the edit are things that are impossible to plan ahead, that’s the part of all this that is the most exciting and rewarding for me. That said, you have the theme of impermanence, it’s essentially what the title Samsara means. So there was that kind of imagery we were looking for, to find that out in the world. We started talking in early 2006, and started shooting in January of 2007.

Ron Fricke: We knew what we were up against and what it would be about. We were actually a lot more relaxed and open and easy about the doing of it. With Baraka we were just kind of in a state of fear. Like, are you crazy? We’re going to go out and make a nonverbal film with no real screenplay, just a scenario? And we’re going to release this? All that [anxiety] was gone for this film, and all that energy was directed toward finding the imagery.

Mark Magidson: A lot of the time you’re finding things that you didn’t plan on. You’re in the field, going to locations that have material you’re hoping to capture, and sometimes you bring that back and sometime you don’t. Portraits are really elusive, and those are some of the most powerful shots in the film, it’s something Ron has a real feeling for. It’s hard to just go out and say I’m going to shoot an amazing portrait today. It doesn’t work that way. Those moments happen by being immersed in these environments. You’re looking all of the time for that stuff. It doesn’t always happen, and sometimes it happens when you’re not expecting it. That’s the image gathering process.

You shot on large-format film again. Since most everything is shot on digital now, how did you arrive at that decision?

Ron Fricke: Mark and I investigated the possibility of going out with HD. But five years ago, when we started, the cameras just weren’t up to par.

Mark Magidson: When we began Samsara the industry standard for digital cinematography was 2K, which nobody would use now. Now there are the Red cameras, and there’s a new 8K Sony camera coming out. The digital world is constantly evolving. You don’t want to go out to all these locations that are very difficult to access and bring back material in a format that’s going to look outdated. That’s the problem with digital—there’s always a better iPhone or digital camera coming out. We needed to use a system that brings back imagery that’s really going to stand the test of time. We used a 70mm camera system that’s been around for 50 years and is still the highest quality way of capturing imagery. There’s a big price to pay getting film stock in and out of places and moving that equipment around, it’s harder now than ever. But shooting in this format is energizing too, it’s about going all out, being on a mission in the search for profound imagery in the ultimate format. Imagery like this delivers real emotional impact, that’s what this is about.

Ron Fricke: Since we’re not using main characters or a storyline, the image is the main character. So it’s important that it’s really high quality and shows a lot of detail. It’s such a cool thing to shoot on those cameras and film stock, to know that when you turn the camera on, even though it makes a lot of noise, that you’re getting this amazing texture that might be bygone soon but digital hasn’t caught up to yet.

How did you decide which images you wanted to pursue, and where you wanted to shoot?

Mark Magidson: You don’t want to go out and repeat what you did in a previous film. That’s challenging, to find locations that are visually of a level of interest and intrigue. People are very visually demanding, particularly in the Internet age with YouTube and everything, there’s a lot of amazing imagery available to everybody. You’re kind of up against that in making a nonverbal film, finding material that rises to that level. You’ve got to have a gut feeling about what’s going to be interesting enough to put on the screen. We as filmmakers are impacted by the times we live in. Samsara has a lot more footage, more locations and more cuts than Baraka had 20 years ago. A lot of that has to do with our own attention spans. When you feel like you’ve seen enough of something you want to move on to something else. You feel like you need to make the cuts faster, and you can’t linger as long. That causes you to burn through material in the edit really fast. So it’s hard to keep it coming for 96 minutes. That’s just on the visual level. Of course having it work as a whole is another subject altogether. When you just have music and image to tell a story, you need a lot of amazing imagery to pull it off.

Ron Fricke: You go to places and see things people just haven’t seen. The planet is loaded with it. And it kind of wakes you up a bit.

Mark Magidson: The imagery is broken down into categories. Like the organic images— shots of nature without humanity, such as the waterfall sequences or the sand dunes. Then there are the factory images, the food processing sequences, the images of people in prayer. Those are locations you can plan on, and you work with local people in each country to get the necessary access.

Unbelievably, you somehow managed to shoot in even more countries that you did for BARAKA.

Mark Magidson: We went to 25 countries. We didn’t know for sure we would go to 25 countries, but we knew it would be over 20: it might have been 28 or 22. You divide that into 95 minutes, and you come up with whatever it is—three and half minutes per country on average, with some having more and some less. And every shot of the film took a lot of work to get. There are some locations where we only used a few seconds. We hiked into a a Native American ruin called Betatakin in Arizona, twice, , that was a two-hour hike each way with equipment in 100 degrees, and that shot is on the screen for about 8 seconds. That’s it. A lot of the film was like that. You want to keep seeing new things.

Ron Fricke: When I get to a location, something just takes over and I know where to put the camera and what to do with it. I’m only looking for a shot or two. I’m not there to develop a documentary about the place, I’m there to get the real essence of it. Because I know it’s in a bigger tapestry with a bunch of other images. That’s kind of the approach. Once you get out there you’re like this lean mean photographic machine. You’re just seeing it when you get there. You just are the image. Because if you’re out there shooting blind you’re going to pick up a lot of stuff that’s just boring, that doesn’t work.

Mark Magidson: At the beginning we were just trying to gather material. But then about halfway through you go okay, we’ve got a lot of this but we need some of that. We need more performances, say. You get a sense of what’s missing. And of what opportunities there are. We happened to be in China about the time of the 60th anniversary of the communist party, so we got that big military parade. We planned that trip to make sure we were there for that, along with all the Chinese factories. You try to take in as much ground as you can with these trips.

Were certain locations more difficult to access and shoot than others?

Mark Magidson: There are the physically demanding locations and there are the access demanding locations. When you’re in a very developed part of the world like Tokyo it’s very tough to get access to film. There was this circular swimming pool that we shot in time-lapse—those kinds of shoots are very regulated and difficult. The parks do not want anything close-up, they don’t want any of the patrons recognizable, that kind of thing. So they’re with you, hanging out and looking into the lens, making sure that everything is okay. It wasn’t that bad, but it’s not just like “here’s a free pass and come and see us when you’re done.” And then there are the locations that are physically difficult, like when we went to Ladakh in India, where we filmed the monastery and the sand painting. It was at 12,000 feet, and it was very cold at that time of year—late November—and you’re huffing and puffing to get used to the altitude. But it’s hard to sit here and complain about how hard this production was. It was a privilege to be able to undertake something like this. You come away from these experiences feeling very lucky, seeing how many people in the world live.

Ron Fricke: All the locations were challenging. It was really hard working inside the pig factory in China. And we almost gassed ourselves in that sulfur mine in Indonesia. It’s all a lot of hard work. The process is just shlepping. Dragging cases through airports, knocking yourself out. We’re shooting a little bit of everything at the same time. That may be why it was a little rough at some of these locations. We’re trying to do time-lapse photography, we’re trying to do portraits, we’re doing slo-mo.

Mark Magidson: It’s exciting to go to remote places. Ladakh was just a wonderful place to visit. Namibia was fantastic. We just saw so much diversity there, desert, jungle, ocean, there’s all the tribal life, there was that desolate sand dune that we got amazing aerials over. That’s a country I’d love to go back to at some point.

Were there any locations you’d hoped to capture but weren’t able to, for whatever reason?

Mark Magidson: The big fish that got away was North Korea. I got to meet Gov. Bill Richardson and he wrote a great letter of introduction for us, and I was back and forth with the DPRK mission in NY as well as though China for 2 years but couldn’t get a go from them. They do these games, these mass performances at this big stadium in August, in which 100,000 people perform. It would have been great to land that but we couldn’t pull it off.

Ron Fricke: That would have knocked you out. This thing called arirang that they do, it’s like Busby Berkeley on steroids.

You get some pretty hard stares of out people.

Ron Fricke: The idea was that it was a takeoff of Tut’s mask. He’s staring at you from eternity. That it’s in all of us, we’re all interconnected in that way. I really liked the sequence with the Himba tribe, with the mother and her baby. Man, she gave me a stare. Sometimes it really works. She could have been from anywhere at anytime. Any culture.

You do some amazing things with time-lapse photography in SAMSARA, traversing physical space as well as time. How has your approach to time-lapse changed over the years and across these projects?

Mark Magidson: Bringing motion control to time-lapse photography is something we started with Chronos, and then really brought further with Baraka. With Samsara it’s not all that different, but we did have some improvements. We previously had pan, tilt, dolly and zoom capability in time-lapse, but for this film Ron came up with a way to lift the camera on a lightweight portable jib arm. We had to be very careful, because you can’t do that in any kind of windy environment because the camera is blowing around. But for interiors it was good, it brought another dimension to it. But all this technology is there to serve the purpose of heightening the emotional impact of the imagery. It’s a tool for that purpose, not an end in itself. You’re viscerally feeling something you haven’t before. Like when you see still photography, there’s a certain inner essence of the subject matter, and we’re just trying to reveal that.

Ron Fricke: Time-lapse is so great. It unleashes on ordinary images unordinary views. We’re all looking to see that. I’ve been doing it for so long that now I have a little more control over it, and understand it better. It’s not just flowers blooming and clouds rolling around—which are beautiful—it’s trying to make a sequence out of it, so that you see this flow. It’s very difficult to do. It takes a day, or an evening to just get off one shot. And then to connect it to another one to make it look like the same place and feeling, is a lot more work than shooting shots. It’s a lot of work to walk away with nothing—sometimes that can happen.

How did you approach organizing all of that material, from all of those locations, into a 95-minute film?

Mark Magidson: It took a year and half to edit, to find that flow, that structure within the material we brought back. It’s as much about finding the way that the images and sequences work best together, as it is creating it. We worked on different parts, with two editing set-ups—I worked on certain parts and Ron worked on other parts. You’re guided by what feels like it’s working, by what’s working profoundly on a human level—in your own heart and mind. If you can’t make it work for yourself you’re not going to make it work for anybody. It’s about discovering that core as much as creating it from whole cloth. It sounds a little out there, but that’s really the process, being true to that.

Ron Fricke: I think that when you’re editing the film, it begins to emerge from all the images have that you’ve collected. You go with the flow of the image. You don’t try to put them together in a certain way, but it’s not easy to do. When you’re in there editing with only images, they need to say something when you connect them and sometimes they begin to say things that you don’t want them to. You just want them to appear, give up their essence, and move on to the next one. You get the meaning out of the feeling you get from it – that’s the meditative part.

Mark Magidson: The building blocks are the shots, and then you have these 2-3 minute sequences—the food processing, the chicken factory, the organic images. How do those sequences go together to make the whole? There’s a lot of ways that can work. There are options there. There was a structure element with the sand painting, which we thought about ahead of time, and within that structure we tried having different kinds of sequences in different orders, and obviously what we ended up with we ended up with. You see imagery at the beginning of Samsara that you see again at the end, but it’s more developed. Those are story points, or structural elements, that are common to all films. It’s not exactly like that, but you have to have a sense that the film is taking you on a journey, and at the end you want to feel that the journey is concluding. It really comes down to making the film with the imagery that you have, and the sequences that you have. It’s not something that’s easily scripted. Imagery can connect in ways in which there’s no way you could have possibly have written. For example, there’s a portrait of a Himba woman in a remote part of Africa, and it cuts to this aerial of the L.A. freeway from her eyes. I love how that cut makes her feel so contemporary. There’s just no way you can storyboard a cut like that. That has to come at the end, after you’ve assembled the film and have it working.

When did the music come into it—during or after the editing process? On BARAKA, you assembled the film with Michael Stearns’s music in mind. Was it the same for SAMSARA with Michael and Lisa Gerrard?

Mark Magidson: This was a distinction from the way we did Baraka, where we edited images to finished music. For Samsara, Michael, Lisa, and Marcello came in after the film was completely edited. We edited the film completely in silence. They saw some of the cuts early on, but weren’t involved in composing any music, or even sketches for music, until after the edit was completed. It’s kind of a severe way of putting a film together, because when you’re doing it silent you’re probably tougher on what’s working, visually, than when you have music. Music kind of softens things and makes everything work better. But we felt that if we can make it work silent it’s going to work really well when we have music. And in general I think that’s what happened. It took some time for the composers to find the musical voice for this, and there’s a bit of the chicken and egg syndrome finding an arc to the music from the opening to the ending plus having it work sequence to sequence, there’s some magic that happened with that.

Ron Fricke: I just wanted to go totally zen with it. Let the images move it along and in the beginning not worry about the music or the sound. I think it was a great way to do a film like this — to cut it and then build in music.

Mark Magidson: The way the music works with the image, and the way we choose the music—going for a kind of spacious feeling—it’s meant to allow room for the viewer to bring something to what they’re seeing, and not be told how to feel about something. The overarching hope is that people who see this feel connection to the phenomenon of what’s going on in the world around them. Connecting to our own humanity. And you don’t want to do that by suggesting a point of view. When you’re using synch sound with image, you’re in the reality world, and when you’re using music with image you’re in that other inner place. That’s where we’re trying to be for the most part.

Was there a political intent behind any of the footage that you captured? I was struck by the sequences shot inside food manufacturing plants, landfills, urban wastelands.

Mark Magidson: It’s not political themes that you’re going after. It’s visually impressive to see the visual development of how people are consuming. It’s not a value judgment. Like some of the food processing factories—it’s happening in a way that’s highly automated, highly mechanized and structured. It’s not about what’s right or wrong, it’s about how it is now. It’s a snapshot of the current state of how things are done. I don’t feel for us that we need to make a political statement. If that’s what you want you don’t have to look very far to find it. When you do that you take the viewer to an intellectual rather than feeling place, it’s not our approach with this kind of filmmaking. It was to provide something that’s different than that.

Ron, earlier you used the phrase “guided meditation” to describe what you’re after with a film like SAMSARA. Do you yourself meditate?

Ron Fricke: I do meditate, yeah. That inner dialogue, all that stuff about what if it doesn’t work, what if they don’t like it—it’s nice to just quiet your brain down. That’s what meditation is all about, I think. You can just get a sense of being alive. The brain’s job is just like your heart: your heart’s job is to pump blood and your brain’s job is to think thoughts, and it’s going to think them 24 hours a day whether you like them or not. And if you’re not onto it, it’s going to think a bunch of lovely ones and a bunch of detrimental ones. You better know how to choose. So meditation’s good, it clues you in on that.

Where does the “guided” part come in? What effect do you hope for SAMSARA to have on the viewer?

Ron Fricke: I think that the substance of what I’m trying to say is really said in a nonverbal form. It’s kind of a spiritual quest. You could say we were all privileged invited guests to this mudball spinning in space. Life is the host. Life invited everyone here, and it didn’t ask anyone to approve of the guest list. And I would love to get that point of view across somehow. I’ve only made 2 or 3 films here. They are what they are. They inspire some people and other people are really put off by it. It’s that way with anything. I don’t know that I’m a great storyteller, I think I just sense that this guided meditation, this nonverbal format, that there’s something strong there. And it can say something powerful that you just can’t say with words. Like when you go to an art gallery, and you’re walking around and looking at great paintings or photography, you can have these epiphanies. You can be really moved.

Considering how many years it took to make SAMSARA, did it even feel like making a movie? Or did it feel like something more totalizing?

Ron Fricke: You just have to be a complete lunatic. You’re not going to have a relationship, a family. It took five years of our lives to do it. Mark is lucky enough that he could bring his family to some of the locations and figure it all out—he really put the effort out. But it’s rough on your relationships. You just have to become this lean mean photographic machine to pull it off.

Mark Magidson: When you say you want to spend this much of your life doing something like this, I sit here and sometimes go—this thing’s over in an hour and half and it took four and half years to make. You sometimes wonder if it was the right thing to spend that kind of time on. When we’re out making the film, you’re not quite honestly feeling all that enlightened. You’re out there getting up early, maybe 4:30 in the morning, trying to catch a sunrise, and it’s really more about being on a mission to bring back the footage. What’s the subject? Where can you put the camera? The goal is to bring back the exposed film that you want. You want to provide a profound experience for people that is an expression of your own life experience. You hope that it touches people in a way that gets them beyond their day-to-day issues, and lets them feel a part of the phenomenon of life. Almost as a snapshot of life around the world. What feels good for me is to try to express my own sense of what it means to be alive at this time. The privilege of being here now, as difficult as life is at times. You hope people feel that. You’re trying to leave something behind that’s lasting.

Could you imagine doing it again?

Mark Magidson: For me, no, not like this. But I said that after Baraka too. Between these three films we’ve been to 57 countries . It’s enough, in a lot of ways. I’m curious to see how Ron would answer that question.

Ron Fricke: I would for sure. In fact not just one but a couple more. I’ve even got another one that springboards off this one. I’ve always been making non-verbal films and will continue to do so. I just hope there’s not as big of an expanse of time between the two.

Be the first to comment