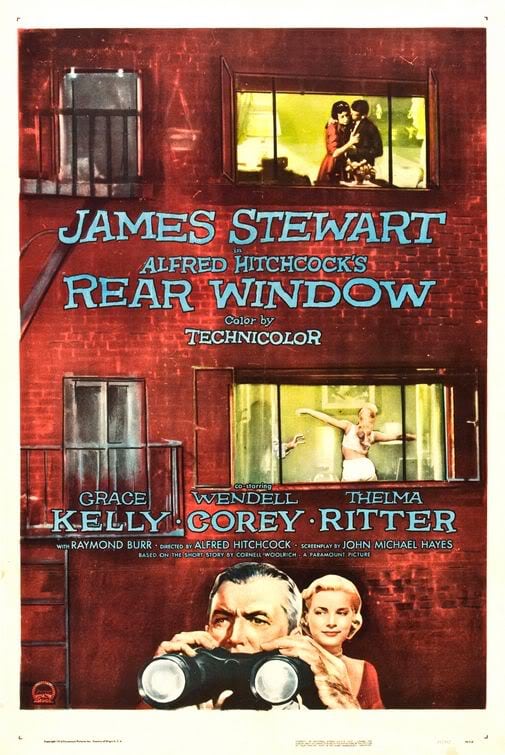

Rear Window (1954)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Cornell Woolrich, John Michael Hayes

Starring: Grace Kelly, James Stewart, Thelma Ritter, Wendell Corey

HCF REWIND NO. 246: REAR WINDOW [US 1954]

RUNNING TIME: 112 min

AVAILABLE ON DVD

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: Winding/repairing a clock in the songwriter’s/musician’s apartment, across from where L.B. Jeffries is being a voyeur.

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

After breaking his leg photographing a racetrack accident, professional photographer L.B. ‘Jeff’ Jefferies is confined to his Greenwich Village apartment, using a wheelchair while he recuperates. His rear window looks out onto a small courtyard and several other apartments. During a summer heat wave, he passes the time by watching his neighbours, who keep their windows open to stay cool. One of them is Lars Thorwald, a travelling jewellery salesman with a bedridden wife. One evening Jeff hears a woman scream: “Don’t!” and a glass break, then sees Lars repeatedly leave his apartment while his wife is nowhere to be seen…

For some it’s Psycho. For others it’s North By Northwest. For me, it’s Rear Window that is Alfred Hitchcock’s most perfect film, a film that, aside from one shoddy process shot of somebody falling near the end, I struggle to find a flaw in. I don’t quite consider it Hitchcock’s greatest work of art or my favourite of his films [that film, which I haven’t mentioned so far in this review and which you can probably guess the identity of if you’re very familiar with Hitchcock’s films, is still a few reviews ahead]. I do, though, consider it the most brilliant example of his astounding directorial talent and technical mastery, as well as maybe his most thematically interesting. Isn’t the lead character just like a film director with his chair and cameras, and aren’t the stories he’s watching just like films? Rear Window is basically about the act of watching movies, and is one of Hollywood’s most pointed films dealing with the subject, yet it can still be enjoyed as a matchless, slow-burn thriller with a sparkling script that gradually draws the viewer more and more in and eventually makes him or her feel just like its hero and feel complicit in his voyeurism. It’s as uncomfortable picture as he ever made, yet is such fun and, like much of Hitchcock, is also unashamedly romantic. The camera rarely ventures outside Jeff’s apartment, yet the film is joyously cinematic. It’s a masterpiece, plain and simple.

Having ended his contract with Warner Bros., Hitchcock was quickly snapped up by Paramount for a nine-picture deal. He took on a project that Joshua Logan had already written a treatment of and wished to direct, but couldn’t make it work so sold it to Hitchcock. It was based on the 1942 short story It Had To Be Murder by Cornell Woolrich. Impressed by his work on the radio series Suspense, Hitchcock enlisted John Michael Hayes to write the script with him. They added all the other neighbours besides the killer and the love story, as well as maybe being inspired by the real-life cases of Patrick Mahon in 1924 and Dr. Crippen in 1910, who murdered their mistress and wife respectively and chopped up the bodies. The whole film was shot on one elaborate apartment-courtyard set which had 31 apartments, eight of which were completely furnished with electricity and running water, and could be lived in. Hitchcock had the entire floor of the studio dug up to accommodate the huge set, while cinematographer Robert Burks had to use every lamp on the lot to light it. While shooting, Hitchcock remained in Jeff’s apartment, the actors in other apartments wearing flesh-coloured earpieces so that he could radio his directions to them. One scene where the man and woman on the fire escape struggle in their attempt to get in out of the rain and argue was caused by Hitchcock deliberately telling both to pull the mattress in opposite directions, while Jeff speaking to his editor on the phone was relocated from just outside Jeff’s apartment to on the phone, using the audio from the completed scene. Rear Window was a critical and commercial hit, and got Hitchcock his second Oscar nomination for Best Director [why on earth didn’t he win?], though it became one of the five Hitchcock films unavailable until 1983 when Hitchcock bought the rights and left them as a legacy to his daughter.

Rear Window opens with the blinds of the window of the title being opened, a brief tour of the view from Jeff’s window [but not showing many of the people yet], and then as adroit a transmitting of background knowledge to the audience as exists in cinema, as the camera shows the wheelchair-bound Jeff’s leg, then moves around his room showing artifacts and pictures that tell a story of a man who was a fearless photographer but was seriously injured whilst photographing a motor race. Jeff has a nurse called Stella visit every morning who initially seems like she exists in the film primarily to dispense homespun wisdom, but quickly assumes the role of both speaker of common sense and provider of juicy black humour which lightens the mood. He also has a gorgeous, glamorous girlfriend called Lisa who Jeff thinks is just too perfect for him, her world of high-class fashion being far apart from his. In fact, he just doesn’t want to commit, and even thinks she’s invading his space, something illustrated by her first appearance in Jeff’s apartment shown as a shadow looming over his face. Rear Window is not just a suspense story. It’s also about someone who has to stop being blind and realise he’s at the stage where he has to change his life and share his life with someone else, a someone else who, in a very daring touch for the time, makes it obvious she’s going to stay for the night in his apartment. “Preview of coming attractions”, Lisa purrs as she shows her night-wear.

Then there’s Jeff’s neighbours, all of whom are in stories of their own, stories in which we will become as embroiled in as Jeff, making us feel like peeping toms. Some of these stories will affect, or be affected, by the main action, some won’t be. All are about different kinds of love. Some mirror, in different ways, the situation of Jeff and Lisa, in particular his fears about marriage. There’s the cute young ballerina who constantly juggles admirers. The childless elderly couple with a dog who like to sleep out on their balcony. The newly wedded couple who constantly have their blind down [there really is quite a bit of implied sex in this 1954 picture]. The single middle-aged woman who makes pottery. The other lonely single middle-aged woman who pretends she’s entertaining every evening. The composer trying to write a song in the lavish studio apartment. And then there’s Lars Thorwald. Deliberately, I think, resembling Hitchcock’s old producer David O’ Selznick, he keeps himself to himself and has a wife who seems confined to her bed. One night Jeff hears a scream and a glass smash, and after that Mrs. Thorwald seems to be nowhere to be seen while Lars is constantly in and out of the apartment all through the night. Jeff tells his old photographer buddy Thomas Doyle, who is now a detective, but can’t prove anything. Maybe Jeff is wrong?

What becomes so disturbing is that we want Jeff to be right, and we feel really let down when, at several stages, it seems that he’s wrong. Rear Window is not a film of big set pieces, and its mounting suspense is very quiet. However, it does become truly hair-raising when the two women in his life set off to collect evidence, Jeff being confined to his wheelchair. There’s one of the single most romantic couple of seconds in movies when Jeff’s face becomes full of admiration at what Lisa is doing. This is when, you feel, he finally falls in love with her and realises what he’s got. Then there’s that amazing climax when Jeff finally has to physically face Lars, when we feel that we share Jeff’s guilt. Not only is Lars there to punish Jeff for what he’s been doing, there’s something pathetic about the way Lars speaks before he attacks which, just for a few seconds, makes us actually feel sorry for him. Of course, Jeff can only defend himself with his camera, its flashes showing as expanding reddish-orange circles [Hitchcock actually exposed some crew members to bright camera flashes to find out what it was like].

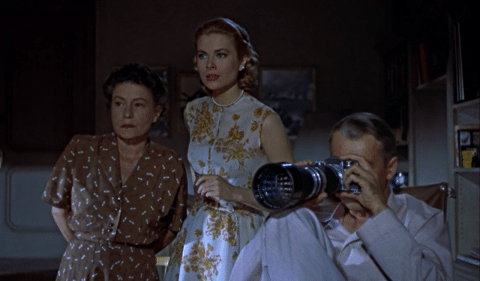

For most of the film the camera never leaves Jeff’s apartment. However, it does do it for a few shots in two separate scenes for effect. One is at the end, and one is during a rather upsetting scene where Lars has killed the childless couple’s dog. The employment of what maybe seems like a breaking of the rules the film has set itself does assist in the power of the moment which is a profoundly disturbing scene for any animal lover. In any case, the supposed technical restrictions Hitchcock set himself in no way seem to hold him back. The camera constantly surveys the apartments, picking up various things here and there, sometimes stopping, sometimes not. It’s pretty obvious we are seeing a set, as in West Side Story and any number of great movies of old, and a set that is constantly lit in a larger-than-life manner, from shimmering rain at night-times to bilious sunsets. I don’t think that Rear Window, whilst having had a great deal written about it like many of Hitchcock’s movies, has been praised enough for how great it looks, and yet you wouldn’t know that it was shot by the same man, Robert Burks, who shot, for example, Dial M For Murder and Vertigo, three films that are all in colour yet all look extremely different. And of course, Grace Kelly constantly lights up the screen swanning around in Edith Head’s beautiful costumes, every inch the Hollywood goddess. Perhaps the only unbelievable aspect of the proceedings is that Jeff would rather look out of the window than get ‘up close and personal’ with her.

Yet Rear Window wouldn’t work as well as it does if it was just technically superlative. It has things to say about the restorative power of love, the deadening sadness of loneliness, and how a seemingly harmless hobby can lead to something far more dangerous. The most touching of the sub-plots is probably that concerning Miss. Lonely Hearts. She eventually finds the strength to go out, and returns hours later with a man, only he just wants one thing and tries to rape her. Later, she almost kills herself, an event almost missed by Jeff and co. because they’re more bothered about trying to prove a death for which there is no evidence of and could be just in their heads, but is stopped by hearing the songwriter’s song Lisa played in full. It’s a lovely illustration of the positive power of music in a film whose soundtrack is uniquely designed. It’s often mentioned that the only pieces of score are the jazzy opening and end titles, though this time round I noticed that one scene is accompanied by a variation on a cue from Rear Window’s composer Franz Waxman’s score from A Place In The Sun. For most of the time, the film’s music wafts in and out like a perfume, supposedly drifting across the apartment building courtyard to Jeff’s apartment, mostly popular songs though often used ironically, like Bing Crosby’s To See You Is To Love You employed to introduce Miss. Lonely Hearts.

Unlike his slightly awkward turn in Rope, James Stewart gives it his all as Jeff. We instantly like him and even later on rarely feel like criticising him for his actions because he’s just like us. Wouldn’t many of us spy on our neighbours in a similar fashion if we lived in a similar place? His best moment is possibly when he sees Lisa in danger and can’t do anything about it. The viewer really feels his fustration. Thelma Ritter and Wendell Corey give great and often amusing support as the no-nonsense nurse and the sarcastic detective. Hayes’ script is maybe dialogue-heavy but it’s terrific dialogue throughout, especially the scenes between Jeff and Lisa, which are constantly ripe with meaning. Rear Window is a film that never really gets old [okay, except for that shoddy process shot of somebody falling near the end, though it wouldn’t have seemed that bad back in 1954]. Its commentary on human nature, notably our desire to look and our fascination with killing [of course Hitchcock is talking about himself too, making this film almost as self-analytical as Vertigo] might be even more pertinent now than it was when the film came out, while it remains a text book example in how to seduce and manipulate an audience…and maybe the best low key suspense thriller ever made. It was remade for TV in 1998 starring the genuinely wheelchair-bound Christopher Reeve, while 2007 saw Disturbia getting so close to the original short story that the writer’s estate sued.

Rating:

Be the first to comment