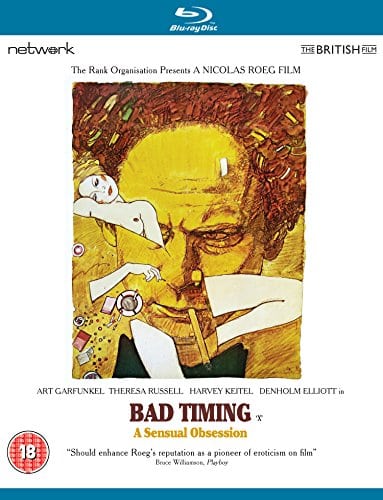

Bad Timing (1980)

Directed by: Nicolas Roeg

Written by: Yale Udoff

Starring: Art Garfunkel, Denholm Elliott, Harvey Keitel, Theresa Russell

UK

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: 26th January, from NETWORK DISTRIBUTING

RUNNING TIME: 123 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Vienna, 1980. American Milena Flaherty is rushed to a hospital emergency room after a failed suicide by drug overdose leaves her unconscious. A psychiatrist named Alex Linden arrives at the hospital with her. He’s the man who called the ambulance and got her to the hospital before she died, and, as he watches the medical care givers trying to bring her back to the world of the living, we flashback along with him through the strange ins and outs of a tempestuous relationship that they had. At the same time, Inspector Netusil’s investigation into the overdose leads him to suspect that Alex may have had more to do with this supposed suicide attempt than he’s letting on….

Bad Timing is the last of a string of five great movies by Nicolas Roeg, films which are bursting at the seams with intelligence, audacity, ideas, innovation and dazzling cinematic craft. It’s a shame that Roeg subsequently began a slow decline into mediocrity [though his next four or five films are still interesting], but it’s entirely possible that he exhausted himself greatly with Performance [co-directed with Donald Cammell], Walkabout, Don’t Look Now, The Man Who Fell To Earth and Bad Timing, so dense and multi-layered are they, with almost every shot, every piece of set design, even every word, having great importance. Bad Timing might possibly be the most difficult film of the five, where even the obligatory sex seems designed to not have any kind of erotic effect whatsoever, though in an odd way it could also be the most relatable….and the most disturbing. It’s one of the bleakest, cruellest but also one of the most perceptive studies of man/woman relationships on screen, as well as being a brilliant example of Roeg’s unparalleled ability to use fragmentary editing, rife with jump cuts, cross cuts and much jumping around in time, to disorientate the viewer and help add meaning and depth to the story he’s telling.

It’s not entirely clear what the origins of Bad Timing are, but it seems that the script was based on a possibly-unpublished Italian novella. Playwright Yale Udoff updated the 60’s setting and relocated the much-altered story from Rome to Vienna. While Art Garfunkel was Roeg’s first choice for the part of Alex Linden, Sissy Spacek was asked to play Milena but turned the role down. Luckily Roeg had began a relationship with Theresa Russell, whom Roeg married after the film was finished and who appeared in three more of his films, so she was cast. Albert Finney and Bruno Ganz both turned down the part of Inspector Netusil and Harvey Keitel got the role just three days before shooting. The deleted scenes on the Blu-ray show that some sex, a [very good] scene of Milena turning up unwanted at a party where Alex is, and most of Dana Gillespie’s footage as Amy Miller, possibly an ex of Alex’s, amongst other tiny bits and pieces, were cut before release. Also altered was a shot of sex melded with a shot of a child because it broke the BBFC’s guidelines. Nonetheless Rank the distributors hated the film, one executive calling it: “a sick film made by sick people for sick people”, and removed the Rank logo from all UK prints of the film. In the US it was barely released and never came out on video. It’s often been assumed that legal clearances for the eclectic soundtrack – Tom Waits, The Who, Keith Jarrett, Billie Holiday – were responsible for this, but it seems that the film just wasn’t liked by the folk who owned it.

Bad Timing is immensely disorientating right from the beginning and is perhaps a little difficult to get into unless you’re used to Roeg’s filmmaking. The titles and the distinctive wailing of Tom Waits play over shots of Alex in an art gallery looking at Gustav Klimt paintings, the disturbing, yet oddly attractive, brooding pictures of intertwined lovers clearly being significant. The observant viewer will also notice Milena in the gallery, but the scene is possibly taking place before the couple were acquainted, though they do visit the same gallery later around the middle of the film so maybe it’s from there. The meditative mood is interrupted by a siren which takes us forward in time to Milena being rushed to hospital, though even this is briefly interrupted by Milena at the Viennese border having her ring being taken off by a much older man who is obviously her husband, and Alex finding Milena after her overdose. As the staff try to save her in the hospital emergency room, we flash back again, and this time to how Alex and Milena meet. She’s the ‘forward’ one, going over to talk to him, blocking his way out of the party they are both at with her leg, and giving him her number. The film then charts their affair while every now and again, sometimes in lengthy scenes, sometimes in quick shots, returning to the present and not only the question of will Milena survive but an increasing mystery surrounding her overdose and what happened immediately after.

Alex and Milena are thrown together by sexual desire but are total opposites, she being the impetuous, wild one of the two who always lives for the moment. She drinks too much and sleeps around, and it initially seems that she’s the character you want to hate, but gradually it becomes apparent that the far more reserved, orderly Alex isn’t a very nice person either and we begin to witness the two literally tearing themselves apart. He wants to control what can’t be controlled. In one scene, he wants sex, the main basis of their relationship, but she wants to talk. The trouble is, they don’t have anything to talk about that doesn’t involve him ‘getting’ at her, and he ends up almost raping her on the steps leading up to her apartment. Whereas Roeg seemed to celebrate human sexuality in his previous films, even if there was often a dangerous edge to it, Bad Timing seems to be almost disgusted with it, something best illustrated when we cut from lovemaking to a bloody tracheostomy. And the climax of the film, which reveals Alex to be a full blown psychopath, is an uncomfortable a sexual scene as exists in cinema.

The weird and wonderful mosaic of cuts Roeg uses to tell his tale actually make the film seem quite modern [in fact the only thing that really dates it is the constant cigarette smoking!] and probably easier to follow than in 1980, though few modern filmmakers do this sort of thing as well as Roeg does and often end up with an incoherent mess. Roeg bends time by inserting flash-forwards and flash-backs which can sometimes only be a single shot, throws in shots of artwork and objects, even cheekily binds Alex and Netusil together so they seem like doppelgangers. One especially memorable moment has Alex and Milena having a row intercut with shots of Netusil obviously several days later in the same room seemingly observing them. The free-flowing nature of Roeg’s employment of film grammar shows how so little tends to be really done with it, but it also provides insight into character psychology, themes, and story. The richness of detail, in a world where every gesture can have a meaning, is almost too much. Cinematographer Anthony Richmond gives us a hazy almost liquid background to Alex and Milena breaking up. Film noir-type shadows [well, we are in Vienna, and I reckon the only reason we don’t hear some zither music from The Third Man, though we do hear something similar, is that there was a clip from that film in The Man Who Fell To Earth] across Alex’s face in two pivotal scenes. Yet all this is in the service of the film and doesn’t seem gratuitous. There’s so much attention to detail, like the way that the settings and lighting become more Gothic, yet Roeg and Udoff are happy to have the climactic scenes almost be a virtual two-hander between Alex and the probing, prodding Netusil. And Roeg uses pop music as well and as ironically as Quentin Tarantino.

Keitel has rarely seemed sleazier, and Russell is a genuine force of nature in her difficult, even contradictory [but so many of us are] part. Art Garfunkel…..well, I can never decide if his passivity results in a wooden performance or is right for his character. Mick Jagger and David Bowie gave similar performances for Roeg, so it’s probably what he was after. Bad Timing might be a hard film to like, but it’s an easy one to admire, even if you find its deliberate coldness off-putting. It doesn’t really offer the escapism of, say, an alien on earth or a man having premonitions of his own death. Instead, it hits closer to home, and has a lot to say about us, our thought processes and our behaviour while showing a superb filmmaker at the top of his form. It’s a terrific, incredibly rewarding film which now looks superb thanks to Network’s Region B Blu-ray, which ports over most of the special features from the Region A Criterion disc. Contrast, clarity and colours seem perfect except for one shot which stuck out because it seemed to have a huge amount of grain, but in a film like this that may well have been what was intended all along!

SPECIAL FEATURES:

*Jeremy Thomas interview

*Original theatrical and teaser trailer

*Deleted scenes

*Image gallery

*Promotional material PDF

*Instant play facility

Be the first to comment