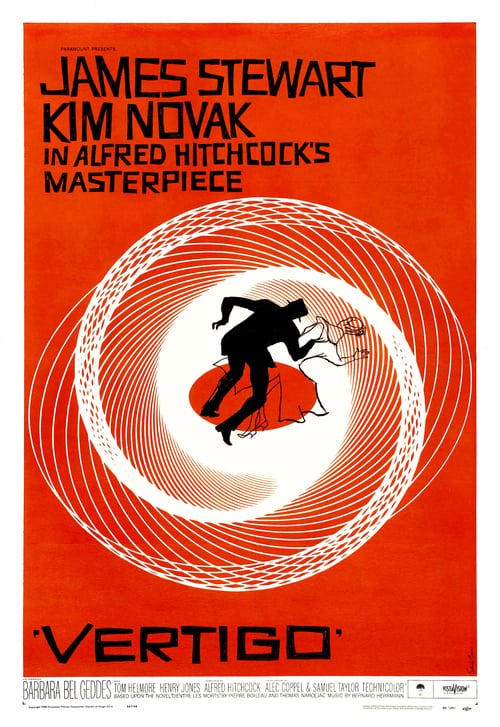

Vertigo (1958)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Alec Coppel, Pierre Boileau, Samuel A. Taylor, Thomas Narcejac

Starring: Barbara Bel Geddes, James Stewart, Kim Novak, Tom Helmore

USA

AVAILABLE ON DVD AND BLU-RAY

RUNNING TIME: 128 min

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: In a gray suit walking across the street past Gavin Elster’s Mission District shipyard and office in San Francisco, in front of columns and a newspaper rack, carrying a trumpet case

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

After his acrophobia and vertigo have resulted in the death of a policeman, San Francisco detective John “Scottie” Ferguson retires. Scottie tries to conquer his fear, but his friend and ex-fiancée Midge Wood suggests another severe emotional shock may be the only cure. An acquaintance from college, Gavin Elster, asks Scottie to follow his wife, Madeleine, claiming she has been possessed. Scottie reluctantly agrees, and begins to follows her. As he does so, it seems that Madeleine is obsessed by Carlotta Valdes, her great-grandmother who, unknown to Madeleine, committed suicide….

In a way I was dreading the time when I would, in the course of my chronological series of Alfred Hitchcock film reviews, get to Vertigo and Psycho, because these two pictures have had a great deal written about them and, being a Hitchcock fan, I’ve read some of this material. At least it was quite a while ago, a good thing because I wouldn’t want to be influenced too much by other writings, even if most of those writings are much better than what I will be able to come up with. I hope though, at the very least, I will be able to transmit some of the passion I have for Vertigo, perhaps the ultimate example of a film which wasn’t much liked on its initial release but whose reputation got better and better, in Vertigo’s case to the point of it replacing Citizen Kane in the 2012 Sight & Sound critics’ poll as the greatest film of all time. Do I think it deserves that title? I don’t think it quite does, though I do believe it belongs in the top ten. Then again, I’m not sure I could make any serious claim for one single film to be the best ever, partly because films can work in different ways, and I don’t think you can always go by what your favourites are either. Vertigo is undoubtedly my favourite Hitchcock film, and I consider it his greatest work of art, though actually if you compare it to Rear Window, possibly the man’s best all-round film, it does have flaws which become obvious, from certain elements of the plot not making sense [next time you watch Vertigo, or maybe for the first time, wonder why Scottie is never asked to identify the body], to the age discrepancy of, not so much James Stewart and Kim Novak, but Stewart and the character played by Barbara Bel Geddes who were supposedly college sweethearts but couldn’t logically have been considering their ages!

In the end, it’s the effect of a film, or more to the point a work of art, that is most important in determining its greatness, and certain flaws aren’t really that important. Vertigo is most definitely a great work of art that can have an immensely powerful effect on the viewer, and watching it again for this review, I was amazed that such a strange, twisted and downbeat film was able to come out from a major studio with major stars in 1958. Yes, the director was Hitchcock, a man as famous at the time for his TV series as for his films, but not all of his recent films had been hits, The Trouble With Harry actually having been a minor flop. Hitchcock was almost left alone to do what he wanted, and he came up with his most personal film [it even has his oft-depicted giving of alcohol to someone else to make them feel better occur twice!], a film in which he let his personal feelings pour out onto the screen, a mostly slow, almost meditative muse on love and death thinly disguised as a romantic mystery thriller, though actually I consider it one of the most romantic movies ever made too. The director even seems to be analyzing himself in a way few filmmakers are even allowed to do, or even willing to do, today, in particular his fondness for making over actresses into a certain type. There’s no doubt, Scottie Ferguson is Hitchcock, a man desperately in love with something he can’t have [he fell for several of his leading ladies], a man desperate to re-model other women into this idealised idea of perfection [which he also did with many of his leading ladies], and a man with a seriously misanthropic view of human relationships.

Perhaps surprisingly, Vertigo was based on a novel, D’entre les morts [The Living And The Dead] by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. Hitchcock had attempted to buy the rights to their previous book but he failed, and it was made instead by Henri-Georges Clouzot as Les Diaboliques. The claim that D’entre les morts was written with Hitchcock in mind has been denied by some, but Paramount Pictures did commission a synopsis of the book in 1954, before it had even been translated into English. Reading the book, it’s surprising how much of the film is there, the plot and some details virtually being the same. Playwrights Maxwell Anderson and Alec Coppel both wrote screenplays, the first called Darkling, I Listen, but the final script, which notably added the character of Midge, was written by Samuel Taylor, instructed by Hitchcock not to read the book. The Wrong Man’s Vera Miles was going to star but got pregnant, and it seems that Hitchcock was never really happy with her replacement Kim Novak. While there was still much studio work, Vertigo made much use of San Francisco locations and added a taller bell tower via paintings and models to Mission San Juan Batista. Two scenes between Scottie and Madeleine just prior to Madeleine’s suicide were cut, and an ending where Scottie and Midge hear on the radio that Gavin Elster has been arrested was shot [villains weren’t normally allowed to get away with crime] but never used. Vertigo only just broke even at the box office, hardly a surprise, though the muted critical response remains odd. Unavailable for many years as one of the five Hitchcock films withdrawn to form a nest egg for Hitchcock’s children, it was re-released in 1984 to huge acclaim. The restoration made the film look new, though ran into some controversy with the addition of certain sound effects, like a fog horn, to cover up defects in the soundtrack.

Vertigo throws you into some action right away, after Saul Bass’s dizzying title spiral patterns, with a roof-top chase and Scottie’s vertigo [though his condition is actually acrophobia which leads to the dizziness called vertigo] causing the death of a cop trying to save him. The scene fades out as we leave Scottie hanging from a roof-top, and showing his rescue would have been a mistake, because we now get the sense that Scottie is suspended between life and death for the rest of the film. The film now slows down and remains at a very languid pace for over an hour. In fact, it’s not even much of a thriller, more an odd love story between two lost, wandering souls. After Scottie has first seen Madeleine, Novak given a superb entrance with the camera tracking across a restaurant to find her and her face coming into profile as Bernard Herrmann’s music expresses such great longing, much time is devoted to Scottie tailing Madeleine, the friend’s wife who seems to be obsessed with her great-grandmother Carlotta, and little happens for quite a while, but there’s a palpable mood of mystery and, yes, death, which becomes stronger and stronger. Vertigo takes its time, the thing that many critics in 1958 most complained about, but it’s never boring, the director making the viewer feel like Scottie – intrigued and disorientated. A scene at a cemetery is shot with soft-focus to help give it a ghostly ambience, and indeed we’re not far from the horror film for much of this movie. The one scene in this part of the film which perhaps doesn’t work too well is when Scottie tails Madeleine to a hotel [which both in terms of exteriors and interiors looks very much like the Psycho house] but is told she’s not there even though he saw her open the window of her room. It’s not a bad scene on its own, it’s just never explained. I guess it doesn’t matter too much considering a feeling of unreality becomes more and more prominent.

Our two wanderers eventually meet when Scottie saves Madelaine from suicidal drowning, and their first conversation afterwards in Scottie’s house is full of hesitant emotion, awkwardness and erotic tension, much of this because of something that is only hinted at but definitely happened – Scottie undressed Madeleine and put her to bed. The romance then slowly develops as Madeleine becomes more obsessed with and even possessed by her great-grandmother. Hitchcock, in a film of startling originality, gives us one retreat into cliché with the two embracing against a background of waves. It’s a rare moment of release in a film which generally doesn’t allow its characters or its audience to smile except for the odd moment with Scottie and Midge. She’s the opposite to the mysterious Madeleine, representing the normality and stability that Scottie isn’t interested in [was he ever? One is told that the two were ‘involved’ and she broke it off, but perhaps because of him?]. Scottie is like many men who will rather chase what they can’t have then be satisfied with what they can.

Eventually Madeleine throws herself off the top of a bell tower, Scottie being unable to save her due to his vertigo, and he has a breakdown, all the events drilling into his head in an audacious dream scene with images that actually hint at what he will discover later on. A year later, he wanders about, thinking various women are his lost Madeleine, until he comes upon Judy, her double. Now it’s here where the film makes another mistake according to some. Vertigo decides to give you its twist here rather than near the end, Hitchcock opting for suspense over surprise. Even I sometimes wonder if it was the right thing to do, and actually there was much debating at the time as to whether it should have remained in the picture. The scene is a bit contrived, but one thing is for sure – the film is far more disturbing from here on as Scottie tries to turn Judy into Madeleine. Scottie becomes a bit of a maniac, and is truly terrifying when he finally finds out that the two women are the same [you may not have seen Vertigo, so I’m not going to quite give every detail away] and forces Judy back up the tower. The force, the power of these final moments is almost un-paralleled in cinema, a desperate struggle by a man and a woman who have terribly wounded each other but who love each other, though in somewhat different ways. The end is depressing, but things couldn’t have really ended any other way.

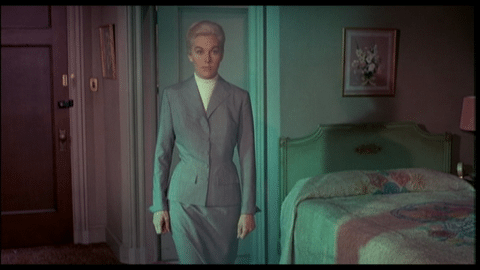

The greatest scene in Vertigo remains the love scene between Scottie and Judy when he’s finally got her to look just like Madeleine. Scottie waits for Judy to come home as Madelaine, but her hair still isn’t right. Herrmann’s music rises in tension as Scottie waits for Judy to finish doing her hair in the bathroom. She finally comes out of the bathroom, unrealistically but poetically bathed in the green light of the sign outside of the hotel they are in, green being representative of Madeleine, and the pain of the faces of both Scottie and Judy is heartbreaking. Scottie finally has his lost love back from the grave [yes, there’s a distinct whiff of necrophilia], and can’t seem to quite believe it, but even more affecting is Judy’s look that’s saying: “I’ve done everything you’ve asked of me, please give me the love I’ve been craving”. The camera spins around them as Scottie temporarily imagines he’s back at the mission where he and Madeleine last kissed [though actually the camera was almost stationery as Stewart and Novak were spun round with a circular set around them], while the orchestra plays some of the most passionately romantic music in film. It’s one of the cinema’s best love scenes, partly because, while it’s intensely emotive with the director truly wearing his heart on his sleeve, it retains an edge about it too.

Vertigo does contain some of the obligatory back-projection, though it’s better than usual and I actually only noticed the majority of it on Blu-ray, a good example of how improving a film’s picture quality can sometimes have negative effects. Some actually say that Hitchcock’s frequent use of this device was to remind viewers they were watching a film, which could be true, I’m not sure. The ‘dolly shot’ used to give an impression of Scottie’s vertigo, where the camera moves away from a subject whilst simultaneously zooming in, remains dizzyingly effective. Cinematographer Robert Burks really outdoes himself with the deliberately slightly bilious look to Vertigo, though of course it was Hitchcock who decided upon the complex and precise colour schemes. I’ve already mentioned green, and it really is used cleverly as in a scene in a courtroom where you can just about notice one door bathed in the slightly sickly green of Madeleine, hinting that she’s still around, but red and gold are also used extensively. Vertigo uses far more music than Hitchcock’s previously Herrmann-scored films. The director sometimes said to the composer: “We’ll just have the camera and you”. Often deliberately circular in form, most notably its arresting opening arpeggio-dominated piece which is as different from the traditional Hollywood opening title as you can imagine, it’s a brilliant score which interweaves several motifs intelligently, most notably a habanera which recurs in nightmarish form during Scottie’s dream, and the mysterious Madeleine theme which later forms part of the Wagner-influenced love theme, a portion of which later becomes very menacing during the final scene. Two songs, the second based on Herrmann’s love theme, were written to promote the film but not used.

Stewart is magnificent in depicting Scottie’s obsession. It’s because Stewart generally comes across as such a likeable guy that he retains some sympathy even when he’s treating Judy terribly. The real revelation though is Novak. Whenever I watch Vertigo, I always tend to think her performance as being a bit weak and unconvincing in the first two thirds, until I remember that she’s playing a woman playing a role. There are even times when she seems to have second thoughts about what she’s doing. There’s so much to notice in Vertigo each time you watch it, though in the end it’s far greater than the sum of its parts. Complaining about plausibility in Vertigo is fruitless, because its exploration of love and death, desire and pain, becomes more and more strange and ends up being virtually allegorical in nature. Hitchcock and his team created a work which ranks amongst such similar tales with comparative universal symbolism and meanings such as Orpheus And Eurydice and Tristan and Isolde. It’s a magnificent film, a magnificent work of art, and the crowning jewel in Hitchcock’s filmography. While not officially remade, it was partially semi-remade by Brian De Palma with Obsession and Body Double, and heavily influenced many other films, from La Jetee and its variant Twelve Monkeys to Last Embrace to La Captive to the comic High Anxiety.

Rating:

Be the first to comment