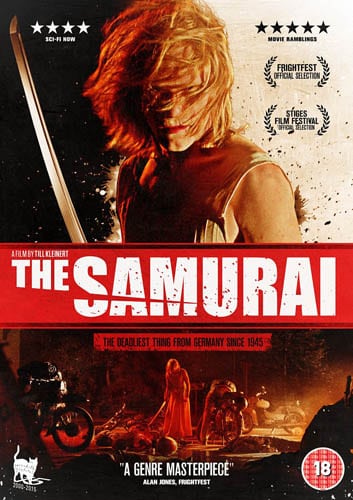

After having played festivals around the world, The Samurai arrives on DVD and on demand on the 13th of April. It is also being screened at the Prince Charles cinema in Leicester Square with an introduction and post screening Q & A on the 9th of April. In the run up to the release we interviewed the film’s writer, director and editor, Till Kleinert about the film.

HCF: Hi Till, How are you?

Till Kleinert: I’m terrific. I’ve just yesterday returned from Belgrade from the international film festival, and it [Der Samurai] actually won in its section which is really great. It played in a section for Subversive cinema and it won, so hooray.

HFC: That’s great. I know The Samurai has been played at festivals, that’s where I saw it first, and I was wondering how it has been received?

TK: I think generally positive. I think there is always different people taking different things from it, you know? Especially, it played a lot of Fantastic Film fests, Horror film fests. I think it was generally received very positively but also as a bit of an obscurity as well. It doesn’t completely work as a proper horror film would or should work. It’s actually something else entirely. There was actually one blogger who described it as not being a horror film at all. With mainstream festivals like this one, it goes pretty well. There’s always people, like there was one in the audience in Canada in Montreal, I think, at a festival who, I don’t know why because I couldn’t get to ask, but he said this is the worst film I have ever seen, but then the rest of the audience butted him down so we couldn’t get a chance to evolve how and in what way it was the worst film he’d ever seen because it might have been interesting actually.

HCF: That’s interesting, obviously everybody takes something different from it. I find it quite a difficult film to categories, not that you should necessarily categorise films into certain genres, but as you said it’s played at Horror film festivals, which was where I saw it, and I personally wouldn’t completely say it’s a horror film but there are a lot of different aspects to it. How do you see it? How do you envisage it?

TK: I always talked about it as a horror film but more because I don’t like how people generally disregard horror films, as if a horror film is something that has to be very generic and very low brow, just as something you wouldn’t touch with a stick. I hate that because I love the genre, I think horror can be so much. My favourite films are horror films but they are very different films. The Exorcist is a completely different kind of horror film than The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, for example, or a film like The Wicker Man, which is one of my favourite films ever, is again one of those where I will definitely say it’s a horror film because it’s about fears and about one guy being consumed by a fear of a liberty and lifestyle that he encounters on this island but it’s not necessarily horrific, you know? It’s not that I’m scared but still I’d say that it’s a horror film because of theme and the motifs that it uses so I think it’s good and often it’s like if you have a more respectable horror film people tend to not call it a horror film. They say ‘Oh, it’s something else. It’s not actually a horror film’ whereas, I feel I’d rather go the other way round. Name the respectable ones as what they are, which is horror films. So I always very consciously call it a horror film even though it’s not one that necessarily scares you, its effects are a bit different but I still call it a horror film. A weird one maybe.

HCF: I think there is quite a lot of snobbery towards horror films in ‘serious’ film circles. Horror films very rarely make the grade in terms of big awards, like the Oscars, and even then, they say things like The Silence of the Lambs is classed as one of the few horror films to be nominated.

TK: But they call it thriller. It’s not a flat out horror film. These monstrous characters like Hannibal Lecter, come up. You can’t be serious telling me this is a serious psychological thriller, so they try to mask it and it’s even worse in Germany. This is a whole different story altogether. I feel like when I travel with the film I feel like in the US or in the UK there is at least a big openness towards these kind of genres trying different things, whereas in Germany I think it’s generally not regarded as something that is regarded as could be being worthwhile. At least from the positions who would grant you money to make the film.

HCF: There’s obviously a few horror film festivals in England, and it seems to be that if there is any genre that is most well thought of in that way, it is the horror genre. There’s not many other kind of genre film festivals that happen in England.

TK: Like there’s not many niche festivals.

HCF: Yeah.

TK: Like, The Samurai falls in two niches actually; it plays in a lot of horror film festivals but it also plays in a lot of Gay and Lesbian film festivals so interestingly enough we managed to find two very specific niches for the film. Maybe making the appeal of the film even more limited.

HCF: I think a lot of horror films tend to be some of the most popular as well really. If you look at some of the box office takings, things like The Conjuring or Saw and Paranormal Activity franchises for instance, they make millions of pounds yet horror films are still seen as an almost grubby sub category to film.

TK: Yeah exactly. I think it’s because most of them make you feel in some amount uncomfortable. I guess some people just don’t like to be uncomfortable. They’re often not very uplifting and motivational films.

HCF: So how did The Samurai come about?

TK: It’s my graduation feature from film school so in many ways it’s just something that had to be done; I had to make a film to graduate and so this was something that felt like it was small enough. It’s basically a two hander; its two actors/main characters and it takes place in one location so it’s something that was handle-able as a graduation feature. The idea, when I create a story for a film it always starts with a central image that then gets explored as I develop the screenplay and everything. In this case it was the image of this lonely figure wearing a dress and wielding a sword and wandering the streets of an empty village. I had a former East German village in mind that actually came to me as a day dream when I went by train through that area. It often starts like that, there is no particular reason yet for the image, it’s just there, but then you start to analyse the dream and that’s where you actually start to figure out the story and the plot. Who is he coming for? What’s his motivation? This kind of thing. Trying to elaborate on this central image without losing its original force.

HCF: The samurai is a strong image. It’s not necessarily one, I don’t think, that you are expecting. Certainly, when I went in to it the film was something completely different from what I was expecting. With the title, your mind goes down one way of imagining what it could be about, like a Japanese samurai film or something like that, an then when you see it and you see this cross dressing man with the samurai sword, it’s certainly an unusual image that you have created.

TK: Obviously it touches some themes and things dear to me but again it’s not consciously created. It’s just there. With the samurai in terms of the expectations, the interesting thing about it is in the UK I know it will be released as The Samurai. The title is Der Samurai, which is a German article [Der], which I think also works or should work internationally because it already gives you a hint, because everybody knows that Der is masculine, and it’ll give you a hint. The image in your mind will already be skewed because there is something wrong with that. Why is it Der Samurai? And it alludes to the more German, dark romantic, fairy-taleish aspects to the film.

HCF: I did think there is something quite fairy tail like and something almost mythological in the film. This one character’s journey through the story, almost like falling down the rabbit hole, where he has this one night where everything unravels but it’s all to do with his situation and who he is, who he defines himself as in this small isolated town.

TK: Yes it’s a journey of self-realisation in a way. Also, I feel like, even though I describe it as a horror film, I see it as a story of liberation, basically. A young man figuring stuff out and losing his shackles. I think that even though it’s sort of outrageous and also a bit violent I think that the eventual message is actually a positive one. And that alludes to fairy tales as well, you always have these situations of children going in to the forest and some sort of monstrous avatars, but they are actually there to help them realise something about themselves, to help them grow up. Jung wrote a lot about this in fairy tales, how our fairy tales directly connect to the archetypes of our growing up and our realising things about ourselves.

HCF: You said you made it as your final piece for Film College, which I didn’t realise and it’s an extremely accomplished piece for it to be part of a film education. How did you get in to filmmaking and writing?

TK: I was always very interested in visual storytelling. When I was a kid I did quite a lot of drawing. I used to draw comic strips so you could say the sequential storytelling was always something I was very intrigued by and even now. At some point when I was 15/16, I think, I realised that it was more fun being out with friends, and with those friends we went out to a video workshop that was there for kids, so they wouldn’t hang around in the streets, so they could do something useful. So they would give us cameras and we would start making films and we made clay animation films and whatnot, and that really got me in to filmmaking but I think my approach is still the same as when I drew comics before. There is always a sequence of images that comes first that creates the story and it’s the context of those images that creates the plot, much more than dialogue or the more literal aspects of it. I guess that’s also why this central image remains so important to me. Like a splash panel in a comic book, it encapsulates all that the story is about. I also storyboard a lot. So that’s my filmmaking approach.

HCF: I find that comics feel to me like a halfway between prose writing and actual films. Again that’s another thing that is still looked down on as an artistic medium.

TK: I don’t quite know why that is. I think a lot of it has to do with the general themes. A huge chunk of the comic book market is used up by superhero comics. And I like superhero comics but you could say that in mass they become a bit redundant and they are a bit juvenile. Of course the themes they talk about has mostly to do with juvenile power fantasies, which is a totally valid subject but of course if you feel like that is all a medium has to offer then you feel turned off by it a bit. There is a lot of different stuff but the general public’s reception of it is that they don’t see it like that because they don’t see that there is other stuff as well. In many ways we also have a lot of trash literature, stuff you can buy at the airport, and there’s a place for that too but you would never say that literature is shit just because there is a lot of these kinds of books. I feel it’s a bit silly.

HCF: I think a lot of it now, because of the growth and popularity of Marvel films and stuff like that, it is partly putting it across that comics is a superhero medium rather than something else as well.

TK: Yeah, but then I wouldn’t even want to look down on the superhero thing because I think you are going down a dangerous path if you start to be selective about what’s worthwhile and what’s not. As you can see with horror cinema for example you have some great writers like Kim Newman or Robin Wood who wrote about horror films and who wrote very insightful pieces on horror films and how they connected to the zeitgeist of their times and I think the makers of those horror films were never even aware of that because they were just trying to make the most gross pieces of trash but you cannot actually make that because they are always connected to something, it will always mean something and sometimes it can mean even more than you ever intended. So I feel like looking down on some sort of artistic expression is very short sighted.

HCF: So how was the experience of making The Samurai?

TK: It was quite straining because we shot mostly at night and outside in the forest and that’s always like, everyone is tired and everyone is cold and particularly for the guy who plays the samurai, Pit Bukowski, it was I think very challenging because he was always in the dress so he got cold very fast and also I think at some point he detested putting on the dress and the wig. He’s actually very interesting in how he portrays him because even though he is cross dressing and there is an androgynous side to him, he is still very masculine and physical. I love that, but he is such a very physical guy he was sometimes uncomfortable just putting on the dress. I would never have thought, because when we talked about it beforehand it wasn’t such an issue but interestingly I think his self-image as an alpha male suffered a bit but he did his job so I am really happy that he was willing to go all that way. With that one shot at the end of the film, the very blatant nudity, that is all him. From the beginning he knew it was necessary for the film and he never questioned it, the necessity of the shot and situation but it was tough to pull off. We had to go back to the location three times over the course of the shoot just to get the right mood. It’s funny, regarding that shot in particular, the film got rated 15 by the BBFC, which I heard from our distributor, which I find hilarious because it means this might be the first full frontal erection ever in British cinema to get a 15 rating. Who knows?

HCF: They do tend to shy away from certainly hugely sexualised male nudity in that way.

TK: It’s basically a close up shot, you can’t get any more blatant than that. Anyway, I like it because I think acknowledging this, because even though there is a lot in the film, people getting decapitated and whatnot, that the film at heart is quite a sweet and tender one so at least I think in the dance scene is where the heart of the film lies. It’s nice that they tend to acknowledge that by giving it a low rating meaning that teenagers could see it.

HCF: It is a little bit of a love story between the two main characters.

TK: It’s definitely a sort of romantic longing that is going on there. It’s funny because people often question the nature of the samurai, is he real or is he merely a figment of Jakob’s repressed desires. I think the film never quite answers that question fully so it’s not quite an actual romance, because it cannot be because it would be mainly self-love, but it is a sort of romantically longing, dealing with a mirror image of an other and flags some of those desires.

HCF: Jakob’s constrained side trying to maintain order and the samurai is almost like an id, trashing everything and doing what he wants.

TK: Exactly and I think he’s right about it because in a way Jakob is contained. He even built a little model village so there is already a small and narrow environment that is around him and he makes it even smaller for himself. He confines himself to a role, the policeman trying to keep up some sort of order that is very hurtful for him. You have the people in the village who are belittling him but that is only part of the problem because I think he should do something about it. He could move away or whatever, so I think in a way the samurai, appearing even though it’s a trial by fire, it also has very healing aspects to the appearance of that guy to Jakob’s soul and mind.

HCF: It brings out a certain strength inside of him.

TK: Yeah. Just aspects of him that were unacknowledged before.

HCF: Coming back to the sexuality, how do you see Jakob? I was never entirely sure about his sexuality. There is that relationship with the samurai but there is also that with the woman in the car. Did you see it either way?

TK: The thing is I think that, yeah, I had my own idea, but I don’t think I even want to say because in a way Jakob is very confused about himself and about his identity but he doesn’t let on because he thinks he has found a role for himself that he can fit in to, basically just a uniform that he wears, and that is all part of it, the fantasy with the girl that he cannot follow through. It’s funny because she doesn’t even know that he fantasises about it but when he leaves the car it almost feels like he is embarrassed or hurt by something she has done. So it’s a complicated manner his sexual identity, let’s say it like that. I have my theory but I don’t think the film has a solution. It’s more like fuel that fuels what we see, it’s not a solution.

HCF: With anything like this it’s certainly better to leave it up to the viewer to make up their mind as it is individual to them what they take from it.

TK: Exactly and I would want everybody to connect to it. You can definitely see there is a sense of outsiderdom to Jakob and he is a very soft character to begin with. Softly spoken, softly mannered, so he is in a way a challenge to a very chauvinist, heteronormative youth society around him but he has also internalised that himself. When he sees the samurai for the first time, the first thing he says, with an internalised fear, is that he shouldn’t go out like that, he might get problems. Jakob is a very funny and interesting character. I like him a lot. He’s a lot like me actually. It’s a bit like a self-portrait of me in my late teens/early twenties.

HCF: I think a lot of people can relate to that feeling of being trapped in somewhere where you have grown up and have always been there and not necessarily knowing yourself yet so I think he is quite a universal character. So you’re a writer and director on the project. Is there either one you prefer?

TK: Actually I prefer editing the most. I am also the editor. You say that the film gets written three times: once while writing, once while directing and once while editing. I’m responsible for all three of those and I’d say I enjoyed the editing part the most which is when it comes together and when it becomes this breathing film entity. When you write it it is still words on a piece of paper, it’s just trying to be a blueprint or a roadmap for what you want to achieve, but it’s not before you have the actual moving image that it becomes a film. I think of all those parts, the actual directing on set was my least favourite part. Mostly because there is a lot of pressure involved. There are so many people and you are basically burning money by the minute just by being there so there is always a pressure to move forward. You just don’t have the time to stop in your tracks and overthink for too long what you are doing. It tends for me not to be where the most creative aspects of filmmaking are. It’s more the preparation and the design. Of course you have the actors on set and the chemistry between them and that’s the new thing, the thing that comes to it, but apart from that I feel the pressure is a lot. I’m always happy when I’m in the editing suite where I can take my sweet time to just connect things and figure them out.

HCF: How did you get funding for the film? Was it something that was provided by the course or do you have to raise it yourself?

TK: We had to raise it ourselves. That turned out to be quite difficult. We eventually got some money from the film board Berlin-Brandenburg, which is the area that we shot in, but it took a lot of convincing, not just because of the subject matter of the film, like as I said that horror films are not regarded as a worthy genre, but also because we couldn’t find a television channel to get involved with it. Generally for you to get film funding by a media board in Germany you need a television channel’s distribution partner or otherwise they don’t feel it’s a safe enterprise. So because of the subject matter, because it was deemed untasteful because of the nudity and violence, all that stuff, it wasn’t possible for us to find a public funding television channel that would say that it was appropriate for them so eventually they said ok we will give you some money but, also because we are a graduation feature and they said ‘ok, so because you are film students the film school gives you a lot of equipment so they take a lot or the risk as well’, so they asked us to fill in the part of the financing, that usually the television channel would take, by crowdfunding. They didn’t tell us to crowdfund but they told us to put some of our own equity in there. So we crowdfunded which went ok. So, we had a mix of public funding and crowd funding.

HCF: The Samurai is quite unusual and quite original. What influences were there on it and on your filmmaking?

TK: I think that also kind of explains the far eastern influence, in the late nineties I was very impressed by the films of Japanese extreme directors like Takashi Miike and Musashi Miyamoto. They were really mind blowing to me, especially Miike. I’d never seen it before, his disregard for tonal consistency. That he would be very willing to give it up if he could achieve something unexpected or an unexpected association. I think his films are all the richer for it. He really embraces the deprived, the deviant but also the silly and ridiculous. I think in many of his films all these elements come together in an unexpected way to create a new experience and new outlook on the themes of his films so I just found it very liberating. A liberating mischief. So that definitely played a role.

HCF: One of my favourite films is Audition.

TK: Of course. It was also the first of his I saw. The way that the film right in the middle, at the centre point where he calls her and she doesn’t answer the phone but she sitting there all silent with the bag in the background and the bag flips over. Oh my God. All of a sudden the film that has so far been a sort of weird, a bit uncomfortable, romantic film turns in to this nightmare and I just love how with the flip of this bag the whole film just switches gears and it’s an amazing feat. Also films like Dead or Alive. In many ways, the ending of Der Samurai is not as far away from the ending of Dead or Alive. It’s also an inspiration; at the end of Dead or Alive you have the two characters who have been fighting for the whole film meeting on a neutral ground that is totally disconnected to everything that went before in the story, it’s just them meeting for an almost abstract showdown. I love that. To give the characters an opportunity to resolve something in this space that is just for them. In a way Jakob and the samurai meeting at the end in the woods is like that to me.

HCF: I really like that shot you do near the end, with the last confrontation.

TK: It was a very complicated shot to pull off. It almost took a whole day for that shot, to set it up, and I am very proud of it because there are a lot of elements involved. You have the actor’s fake torso, the different effects stages, the smoke, the sparks, the blood, you have Jakob with the sword, the camera that is on a very complicated rig that makes it possible to spin on its own axis and it’s shot in super slow motion so any little glitch of timing will very visible, so it’s a very complicated thing but it was a lot of fun to do. There is this big fireball that happens and that’s actually a mistake. It wasn’t planned. Originally we just had the three elements: we had the smoke, we had the sparks and the blood, but in that particular take the smoke got so hot that the sparks ignited and we all of a sudden had this really beautiful fireball but also everyone was quite shocked. The camera operator was very upset because he was very close to it, so in terms of health and safety it wasn’t perhaps the best situation but it was definitely the best take we had so we ended up using it. It was a lucky moment.

HCF: What’s next for you?

TK: I’m working on several things. So far none of the have been greenlit so I’m still figuring things out. I’m writing something a bit longer for television. It’s a limited series of eight episodes that is also horror/mystery and I really hope it happens because it has been on my mind for a very long time now. There is also another idea I had for something which is a bit easier to pull off. A little feature film. A nasty little story about a body swap. I think also, if there is a genre that is less respected than horror it must be the body swap comedy. But it’s not a comedy. I had a very nice idea so that might be something that I might do in the future.

Be the first to comment