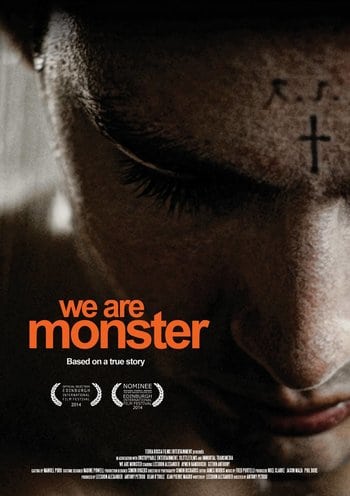

We Are Monster

Directed by: Antony Petrou

Written by: Leeshon Alexander

Starring: Aymen Hamdouchi, Gethin Anthony, Leeshon Alexander

WE ARE MONSTER (2014)

Directed by Antony Petrou

No matter what tabloid rhetoric may say, prison never has nor ever will be “a hotel”. For the perks of an old games console between a floor of people, and a pool table where the cues have long since blunted, it is a terrifying place where there exists a real danger of violence every day. Feltham Young Offenders Institute is no exception, and down the mundane (but beautifully captured) corridors a threat brews. Telling the true story of a tragic occurrence, where a known racist murdered his Asian cellmate, we are told from the beginning these events reach boiling point. What follows is an hour and a half of seeing it aggressively simmer.

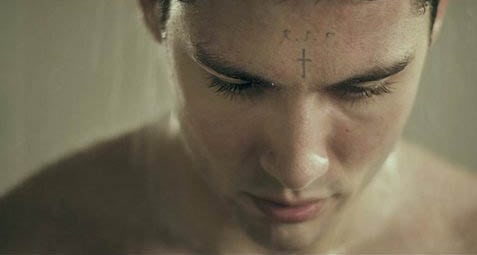

We Are Monster is a movie with high ambitions. Telling the story from the perspective of its villain Robert Stewart (Alexander), director Petrou aims to depict what may have been going through his head during the 6 weeks he shared a cell with his victim Zahid (Hamdouchi). When a film is based on true events this sort of narrative is no mean feat, made all the more difficult when the story is told through an unsympathetic character. Luckily Leeshon does a first rate job as both the schizophrenic murderer and the devil on his shoulder. In a plot decide that allows us into the mind of a loner, Alexander does a duel performance, sharing much of the running time with himself. This gives the movie a chamber-drama like quality, with the two sides of him going back-and-forth. On one hand we have a frightened and misguided young man, and on the other a goading and psychotic bigot who shoots out expletives and racial pejoratives at rapid fire. This second, more menacing, Stewart taunts his prior attempts at finding a release (self-harm plus a sex line), nurtures his destructive side and projects flashbacks on the wall. And credit to Alexander, he plays each persona with very different mannerisms and nuances. Truly, his is a performance that deserves as much respect as the character craves.

Nonetheless, at the heart of any effective character study there ought to be an interesting character. And whilst I strongly commend Alexander’s ability as an actor I’m less impressed by his ability as a writer. The motivations we’ve seen before – a stereotypically feckless father who appears only to scare and beat his kids or mutter something prejudiced, plus a little playground torment. In real life these may be personal factors that increase the likelihood of somebody growing up to be a racist. But in terms of screenwriting it feels like these all too brief exposition scenes are cheap shortcuts and greatly simplify why young people develop resentment for those outside their ethnic origin. Particularly a film concerned with racism in the institutional sense. There is scant analysis of the dynamics that inform prejudice at a societal level or how the structures we have to protect us may breed it. Furthermore, while the voice in Stewart’s head is an interesting narrative idea it is also greatly overdone. This kind of device works best when there is a conflict in the character and they are seduced by their demon. Yet here our subject is fairly aligned with this way of thinking from the start, with the only real point of contention being smoking weed vs. burning a fellow prisoner. Unfortunately the absence of an arc means the dialogue between the two sides of Robert become very repetitive very quickly.

It’s not only our lead character that lacks psychological depth, with the secondary ones being character-types rather than characters in their own right. Zahid is written as an all-round nice guy, who seems more an obvious foil than a person in his own right. Watching him be friendly, repeatedly apologise for letting down his family and discuss the possibility of working with The Prince’s Trust after release is simply not enough to feel for him. This is problematic considering the drama comes from the circumstances that surround his murder and the injustice facing his family. And then we have the police officers whom are repeatedly shown to be lazy, bigoted smokers. Of course in real life they behaved abominably, though we can assume there is a wider cultural problem in the force than that which the film offers. When they read Stewart’s racist and violent letters they all too easily dismiss them as ‘banter’ to the point of it being both unbelievable and unintentionally funny. Instead of providing an interesting layer of analysis as to how the system facilitates or corrupts those it holds captive, it rather seems like Alexander found these scenes inconvenient and so did the writing equivalent of sweeping them under the rug. This is very frustrating as I really wanted to like the film more than I did. It tells a worthwhile story about a shocking negligence on the side of the law. Yet just because the rights and wrongs of racism are simple (i.e. don’t be a racist) it doesn’t mean the characters that are have to be too.

Be the first to comment