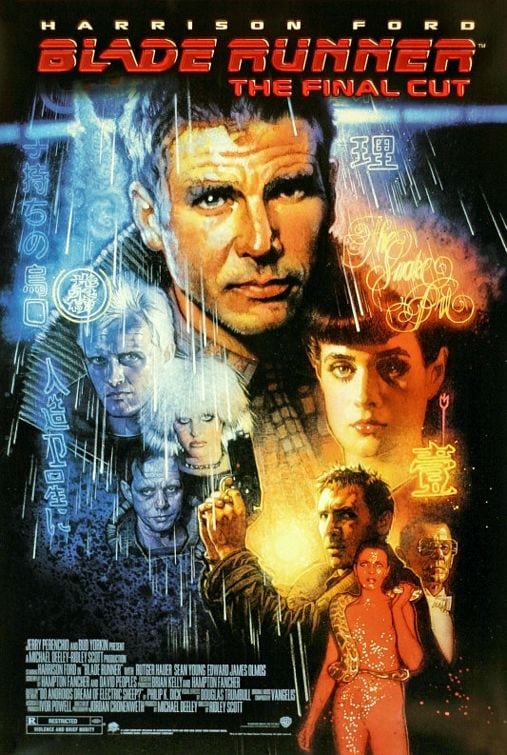

Blade Runner (1982)

Directed by: Ridley Scott

Written by: David Webb Peoples, Hampton Fancher, Philip K. Dick

Starring: Edward James Olmos, Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young

USA

IN CINEMAS NOW

RUNNING TIME: 117 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

2019. Humans have genetically engineered replicants, which are essentially artificial humans designed for labour and entertainment purposes, but are only allowed in off-world colonies. Rick Deckard is a retired blade runner, a hunter of replicants who illegally come to earth. A group of replicants makes it to Los Angeles seeking a way to extend their life span, replicants only having a built-in four year life span, and this group nearing their end. After watching a video of one of the replicants shooting another blade runner, Deckard reluctantly goes back on the job. First step – the Tyrell Corporation, the company which built the replicants….

Well, I thought it was boring, depressing, stupid [for God’s sake, a villain who saves the hero’s life!] and didn’t fulfil the promise of its action packed trailer which led me to expect so much. Yep, they were my first impressions of Blade Runner, which was already beginning to be regarded more and more highly, when I first rented it out on video. Something happened though. The thing stuck in my mind, and I made a point of watching it when it was next on TV. This time, I liked the film rather more, partly because I was really getting into old movies and loved the film noir elements, but still felt it lacked something. Then the Director’s Cut came out and I went to see it. Wow! What a film. I felt as if I genuinely ‘got’ the movie. However, I missed that much hated voiceover, I wanted it back. There was something about Harrison Ford’s world-weary narration that fit the movie so well. So you see, while I do now adore the movie and have done so for a considerable amount of time, none of the various versions of Blade Runner are totally satisfactory to me, because they all [except for the US Theatrical Cut which is just the International Theatrical cut with less violence] contain certain bits and pieces which are unique to them. The Final Cut may correct the film’s errors and be director Ridley Scott’s true vision, but I’m not too keen on the way the unicorn scene, which was so haunting and dreamlike in the Director’s Cut, was re-edited to make it longer and, to my eyes, more jarring. There are some great shots in the Work Print which I think belong in the film. And I just love that narration. I guess that the best version would be the Final Cut with the narration from the Theatrical Cut…well, most of it, I mean you’ve got to keep that dark ending!

Many critics in 1982 thought the film to be lacking in humanity, and that the detailed future [or now, not so future] world that Scott so meticulously put on screen drowned out the story and characters. There is no doubt that Blade Runner is done in a very detached, even distant manner, but this is totally appropriate considering that, more than anything else, it’s about living beings, whether real or artificial [and however you interpret certain aspects of the film] struggling to gain, or regain, humanity in a world which seems to have largely lost that quality. In fact, successive viewings, despite its nightmarish elements and graphic moments, reveal considerable emotion and beauty to the film, even if it avoids sentimentality until its penultimate scene, where it’s totally justified. But then, it’s also possible to totally tune out and immerse oneself in the film in a more abstract manner, letting the details, textures, the smells [yes, you can almost smell things, the film is so vivid] just overwhelm you.

Phillip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? was first adapted into a screenplay as early as 1972 by Robert Jaffe, and as a reportedly terrible comedy. Hampton Fancher’s screenplay, which was actually written with Robert Mitchum in mind, was optioned in 1977. It was for a much smaller, more interior movie than it eventually became. After successive rewrites Scott got David Peoples to do some alterations though it was tinkered with throughout production. Dustin Hoffmann was considered as the star for some time. Just as principal photography ended, Filmways withdrew financial backing, but ten days later producer Michael Deeley secured financing through a three-way deal between The Ladd Company [through Warner Bros.], the Hong Kong producer Sir Run Run Shaw, and Tandem Productions. An actor’s strike was the only reason that they had time to build all the sets, but the production, which was a tense shoot anyway due to things like Scott unintentionally offending US crew members, was soon badly behind schedule, chiefly due to Scott requiring lots of takes and having the set lit, shot, the film rewound, and then rerecorded over and over again with different lighting. For the first five days he just shot smoke! Eventually the investors took over and fired Scott and Deeley before later relenting as long as they had final cut. They insisted Scott not put in the unicorn dream scene, that he shoot an absolutely stupid happy ending which contradicts much of what came before, and that he add that narration, though it must be said that the first few drafts of the script had narration too. The film still flopped, but of course its reputation grew very quickly. Prompted by the accidental finding and showing of the Work Print, the Director’s Cut came out in 1992, though Scott was too busy shooting 1492: Conquest Of Paradise to devote much time to it and considered it unfinished until 2007 when he was finally able to complete the film to his satisfaction.

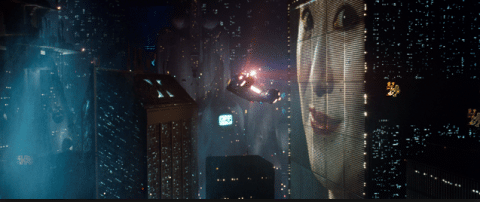

Seen on the big screen, Blade Runner’s fabulous opening scene is even more awe-inspiring, as the camera slowly tracks over the awe-inspiring model of the city of the film, fire belching out of the top of some of the buildings like dragons breathing fire, and Vangelis gorgeous music soaring. Right from the beginning it’s amazing how well Blade Runner’s ‘in-camera’ effects hold up, give or take a couple of matte paintings [though to me eyes a great deal of modern CGI sticks out far more, one of the many reasons I loved Interstellar]. The early shots of the top of the city, replete with those great looking but immensely dangerous [if you think about it] flying cars, I remember when I first saw the film as being somewhat misleading considering most of the film takes place on the way down below, but part of the film’s genius is that it begins by showing you the coolest, most elaborate future images that were possible in 1982, then takes the viewer down to a much grungier, messier world that, despite a few elements dating, seems even closer to the way we are going than it must have seemed when it came out. Giant global corporations ruling, environmental decay, overcrowding, technological progress at the top, poverty or slavery at the bottom – it not only set the template for nearly every major future cinematic world for years to come, but seems to be coming more and more true. Of course Scott and his designers were themselves influenced were things like the French comic magazine Heavy Metal and, the granddaddy of all future dystopia movies, Metropolis, but the influence of what they came up with is still being felt, whether in cinema, other forms of media or art or in real life.

Much of Blade Runner does indeed move at a slow pace, Scott wanting the world he’s created to be as important as the story which takes place in it and its themes. This is sometimes taken to really daringly artistic effect, such as the many scenes set inside rooms where the lighting constantly varies because of what is taking place outside, though it also increases the sense of paranoia. Elsewhere, Scott wants us to feel everything, while, despite all that neon everywhere, imbuing much of it with a melancholic, hazily alcoholic and narcotic feel straight out of 40’s film noir [and isn’t it odd that this aspect has also been carried over many times since?], though Sam Spade never had a device that could get inside any photograph and nose around in it – a private eye with a private eye – and, while much of the first half does involve Deckard doing investigating, what he’s actually trying to find, though he doesn’t know it for a while, is the meaning of life. Then there’s femme fatale Rachael, though she isn’t too well handled, especially in what could be the worse scene in the film, where Deckard, overcome both by lust and a desire to get an emotional response out of someone who is probably a replicant, all but roughly sexually assaults her and she gives in. Even if you take it as being the only way Deckard knows how to treat women in a world where the fairer sex everywhere seems to be objectified, the scene is unconvincing and terribly written.

Then again, there is a distinct correlation between sex and violence throughout, and watching it again I was surprised at how brutal and uncompromising a movie Blade Runner is. The death scene that always stuns me with its fetishistic combination of beauty and savagery is when Deckard shoots the replicant Zhora in the back as she crashes repeatedly through plates of glass [a scene which until the Final Cut contained a glaring mistake where you could see obviously detect a stuntwoman, and its ‘fixing being an excellent example of how CGI can be used to improve older movies, you reading this George Lucas?] and then falls onto the ground outside, surrounded by pieces of glass gorgeously reflecting neon. Pris’ gymnastic attack on Deckard remains really uncanny, partly due to the careful way it’s built up to and its macabre setting. Though not an action movie, what action there is in Blade Runner is highly exciting though interestingly relies a lot of close-ups and handheld camerawork which makes it seem part of a modern action film, though not taken to the nauseating extremes of much of what you see now. In fact, Blade Runner often makes brilliant use of close-ups of characters [especially Rachael], often taken from the side and just taking up one half of the screen.

In any case, I never really care about the so-called love story in Blade Runner but, thankfully, there’s a great deal to care about elsewhere, even concerning minor characters like J.F.Sebastian, the inventor who touchingly builds loads of mechanical toys to alleviate his loneliness. I’ve always loved this particular character. The plight of the replicants, killers who become more and more sympathetic until the line is totally blurred between hunter and hunted, good guy and bad guy, culminates in the heart breaking moment where Roy Batty, the leader of the small band of outlaw replicants, finally unleashes [after signs of it in Tyrell’s tower] his growing humanity when he reacts to the sight of his companion Pris being dead. Batty’s own death scene is one of the most poetic in cinema, whether it be the beautiful images or Rutger Hauer’s speech, to which he added two lines of his own. It’s tragic, but also hopeful, because Batty’s saving of Deckard’s life has suggested that man and machine may find some peace.

There’s been much debate over whether Deckard is a replicant or not. Some say that Scott only decided that he could be years after the first release of the film, though this is actually inaccurate. I actually wondered about this the second time I saw the Theatrical Cut, me already being prone to reading too much into films, and it’s certainly hinted at. Later versions make it more obvious, though it’s never actually stated. In any case, if one looks at the wider themes in the film, then by the end, it matters little. While the film is as rich in thematic complexity as anyone could wish for, from religious metaphors concerning God and the creation of life to free will, what is being asked above all else is what is the defining quality of humanity, and it suggests that it’s not intelligence, not strength, but empathy: the ability to share the emotions of another. As it does this, Blade Runner examines the impact of technology on human society, existence, and the very nature of humanity itself in a way which has a great many parallels to modern society, most obviously the way people are becoming increasingly insular as technology invades the realm of personal interaction. One tour around the internet will reveal an extreme lack of care and consideration with anonymous posters tearing each other apart behind the confines of a computer screen. Blade Runner may not have got all the details right, but it predicted the basic direction we are going in nonetheless.

Harrison Ford didn’t enjoy himself much whilst making Blade Runner, but the dissatisfaction that spills over into his performance actually makes it more effective. The film is filled with iconic performances and characters that you never forget, be it Edward James Olmos’s Gaff, Deckard’s boss who creepily shows up everywhere and possibly knows everything right from the start, or Daryl Hannah’s replicant Pris with her disturbing movements. Vangelis’ score, which has been a source of trouble for fans because Vangelis won’t release a full version of it [though there are bootlegs and an official re-recording of most of the score by someone else], is a work of art in its own right, from its atmospheric underscore to its evocative source music proving that synthesisers can sometimes evoke as much emotion as traditional instruments. The pulsating end title theme is a great example of a dance music anthem before dance music. Blade Runner isn’t anywhere near perfect, which is why I haven’t quite given it the full ten out of ten rating [sorry Matt Wavish!]. Clumsy plot devices always stick out for me, like why do they test all new employees of the Tyrell Corporation and spend lots of time asking bizarre, complicated questions when they have photographs of all the Replicants on file? Some elements of the plot, like the Rick/Rachael relationship, really needed more work, proving that maybe Scott did get a bit carried away with building his world and making everything look perfect. And, as I said at the beginning, none of the versions totally satisfy me because most of them lack things I love that are present in others, though that’s probably just me and I shouldn’t let that really influence my opinion of the film too much. In any case, are many other science fiction movies as truly thought provoking and deep? And have we ever been to as vivid and believable a world of the imagination, a world so perfectly combining the past, the present and the future?

Be the first to comment