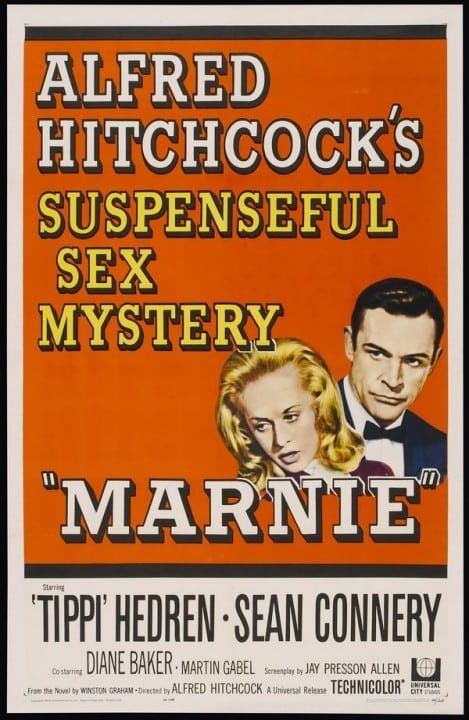

Marnie (1964)

Directed by: Alfred Hitchcock

Written by: Jay Presson Allen, Winston Graham

Starring: Diane Baker, Louise Latham, Sean Connery, Tippi Hedren

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME: 130 min

THE HITCHCOCK CAMEO: Entering from the left of the hotel corridor from a hotel room after Marnie Edgar has passed by with a bellman carrying her things. The director looks guiltily at the camera.

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Margaret “Marnie” Edgar is a troubled young woman who has an unnatural fear and mistrust of men, thunderstorms, and the colour red. She is also a thief, using her charms to get clerical jobs without references and then stealing the contents of the company safe and changing her appearance and identity. Her mother Bernice questions how Marnie is still alone yet has so much money, and is very cold to her daughter. Marnie gets a new job at a publishing company run by widower Mark Rutland, but Mark is a customer of Marnie’s latest victim, and recognises her, though he doesn’t tell her and instead befriends her and waits to see what happens….

And so we come to quite possibly the most divisive of all of Alfred Hitchcock’s films, at least in terms of balance, with the overall opinion generally split half and half on the picture. It’s either a poorly made, unconvincing, overly talkative, boring echo of Spellbound and Vertigo [I prefer to call it Spellbound revisited through the maturity and intelligence of Vertigo], forever tainted by its tortured making-of process, or it’s the director’s last masterpiece, an impressively daring, uncomfortable, highly stylised and very personal work that proves that great art can sometimes come from the most troubled situations. Though the film may certainly have some considerable flaws, I’m pretty much in the second camp, though that may be partly because it was the first Hitchcock film I ever saw. No, it wasn’t Psycho, or Strangers On A Train, or North By Northwest, it was the very strange and leisurely paced Marnie, yet I was absolutely transfixed by it, even if I was too young to entirely understand everything that was happening. There was something actually really exciting about the picture, I distinctly remember being so caught up in the characters and their plight. Even now, there’s something so painful, yet also so compassionate, about it, a film full of feeling, if feeling that is often ambiguous and confused. I still really love Marnie, though of course it’s sometimes hard to entirely separate one’s love for a film from an examination of its quality or lack thereof.

With his preceding three films North By Northwest, Psycho and The Birds, Hitchcock basically predicted future trends in major, commercial cinema, the man being incredibly ahead of his time. With Marnie, he returned to a strong personal obsession for him [though there were shades of it in North By Northwest]: love as a twisted corollary to hate. It’s far more in the Hitchcock tradition of not just Vertigo but Notorious, Rebecca, Suspicion, Under Capricorn and others. It’s as if Hitchcock had pushed himself as far as he could go and retreated to his comfort zone, albeit now with greater depth, and at least there’s considerable emotion in the picture, something which one can’t really say about Hitchcock’s final four films. Marnie remains perhaps the closest example of a cult movie in Hitchcock’s work [I suppose decades ago Vertigo could be said to have fulfilled that role until it was looked at again during its re-release and suddenly started topping ‘best film’ polls]. One thing common to many cult movies is that flaws which, to folk who are not fans of a film, are jarring and sloppy can see, to seem to its lovers to actually add to its quality. Marnie has been much criticised for its artificial aspects like obvious studio sets, painted backdrops and back projection, but many of its fans say they add to the dreamlike quality of a film influenced by German Expressionism. Which is it? I guess the truth lies somewhere in the middle. It’s possible that Hitchcock’s falling out with Hedren led to him not caring as much about certain things as he should, but the result definitely adds to the odd effect of the film [and I don’t really understand why the back projection is heavily criticised in Marnie and hardly ever in most other Hitchcock films].

Hitchcock wanted to make Marnie in 1961, it was intended to be Grace Kelly’s big return to the screen, and he got Psycho’s Joseph Stefano to write a script which closely followed Winston Graham’s novel about a troubled female kleptomaniac, but the subjects of Monaco objected to their Princess playing the role, and Hitchcock made The Birds instead. After its release, he resurrected the Marnie project, and The Birds’ Evan Hunter wrote another script that greatly altered the story, notably melding the husband and psychoanalyst parts into one, turning an admirer of Marnie into an admirer of Mark, and altering the event that caused Marnie’s traumas, but was fired when he objected to Mark raping Marnie, so Jay Presson Allen came on board. Despite Eva Marie Saint, Vera Miles and others being looked at, it was only ever really going to be Tippi Hedren playing Marnie, though Marlon Brando and Paul Newman, both considered, would have been interesting as Mark. Hitchcock’s infatuation with Hedren became nasty on set, with the director becoming extremely possessive and controlling, and, according to Hedren, eventually demanding sex from her. When she refused, he never spoke to her again. Co-star Diane Baker claims Hitchcock behaved inappropriately with her too. Hitchcock cut five min [content unknown] just before release and the studio insisted on part of Bernice’s final speech, concerning Marnie’s father, being removed, though it was too late to recall all prints. Despite its reputation as a flop, Marnie did actually make money and was the 22nd highest grossing film of 1964. Critically reviled, its reputation has greatly increased, though its quality is still much debated.

Even haters of the film must admit it gets off to a fantastic start, the first shot being a close-up of Marnie’s yellow handbag as she walks past the camera and into the distance down a train station before we cut to a man crying: “Robbed!” For a while we follow Marnie on what has obviously become a usual routine for her. She escapes from where she has had a job and robbed the company safe, colours her hair, changes her identity, and throws the key to the safe down a drain. She then visits her horse, Forio, probably her closest friend. When she rides him, it’s as if she’s having the only release from her tormented life, and a tormented life it certainly is. She goes to stay with her mother Bernice, and she’s really distant, seemingly incapable of showing any love for her daughter, though she’s certainly nice to the young daughter of a neighbour. These scenes are brilliant in their understated but extremely uncomfortable tension. No, Marnie doesn’t contain much in the way of conventional thrills, and does rely heavily on dialogue for much of the time, but for me the only section that really suffers in this respect is around the middle, when Mark and Marnie move from one location to another and just whittle on and on. The Hitchcock of ten years before would probably have cut much of this down.

Hitchcock does give us one superb suspense sequence a third of the way through when Marnie is robbing a safe, with her cleaning it out on one side of the screen and a cleaner doing her cleaning on the other. We are totally on Marnie’s side, and feel like gasping when the silence is broken by her dropping one of her shoes [she’s going barefoot so she can’t be heard]. We are only given the information that the cleaner is actually deaf once Marnie is gone. Mostly though, Marnie is concerned with the very screwed-up love story [if it can really be called that] at its core. It soon becomes apparent that Marnie is not just terrified of the colour red [though this is sometimes inconsistently done – there are instances where Marnie is near red and is perfectly fine] but is frigid. However, Mark is basically a sexual blackmailer, forcing Marnie to marry him, and is clearly ‘turned on’ by the fact he has caught and trapped a thief. This comes to the fore in the rape scene, which despite being highly uncomfortable and making Mark unsympathetic, is essential to the story as told in the film. Frustrated after spending several nights on a wedding cruise separate from his wife, Mark storms into her room and tears at her nightgown, Hitchcock achieving a far more powerful result from showing Marnie’s legs rather than full nudity. Ashamed, Mark puts the gown round her and comforts her, but can’t help himself as he lowers her onto the bed and we see an agonising close-up of Marnie’s face, totally cold and emotionless. What is so disturbing is that Mark probably doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong [though of course attitudes were a bit different then].

Marnie is easily Hitchcock’s most fetishistic work, be it the first kiss between Marnie and Mark where the camera goes so close to their lips that it almost feels pornographic, or the director’s fixation with blonde hair reaching its peak, or even single kinky cuts like Mark grabbing Marnie by the wrists followed by a close-up of her leather riding boots, not to mention crude symbolism like a giant sea vessel pointed right at the camera as if it were about to be driven straight into the street where Bernice lives. The film, is without a doubt, a study of Hedren, be it her figure, her face, her hair, her body, whatever, and, while it’s easy to feel uncomfortable about it, it’s interesting that she says Marnie remains her favourite of her films despite what she went through whilst making it [and maybe after, considering that it’s reputed Hitchcock virtually ruined her career afterwards].

But then again, so much in this film is interesting. It may not be full of thrills and spills, but it’s definitely full of unusual, sometimes even unexplained touches, like the mysterious man Marnie meets at the racetrack. While in some ways Hitchcock’s darkest film [yes, more so than the more conventionally frightening Psycho], it’s full of often devastating emotion, bleeding off the screen just like the many instances where Marnie’s fear of the colour red is suggested by red flashes, from the intense moment when Marnie has to shoot her injured horse to Marnie’s several touching pleas for love and help. The script mostly avoids psychoanalysis except for one jokey [the film’s only] scene which gently mocks it. A hunt sequence and subsequent horseback pursuit gives the highly claustrophobic film some real outdoor air, but it also seems like they strayed in from another picture. Then you have the final revelatory flashback, shot with de-saturated colour, introduced by Marnie speaking as a young girl, and by scenery obviously moving around in stage fashion [but who cares?], which could be the most disturbing scene Hitchcock ever filmed, particularly when a sailor [an early appearance by Bruce Dern] tries to kiss little Marnie.

Hedren has always come in a lot of stick for her performance, but I think it’s fantastic, and entirely appropriate for her character’s state of mind, while Connery nicely plays on the dark side of his James Bond persona. Saying all this, it’s probably Louise Latham as Bernice [and yes this film is full of deliberate references to Edgar Allan Poe, who Hitchcock read as a child and claimed inspired him to make suspense films], who gives the stand out performance, so creepy and sad, even if she looks far too old to be Marnie’s mother if she had her at 15 [incredible makeup job by Howard Smit though]. Bernard Herrmann’s score is very loud and ‘in-your-face’, with the composer deliberately going for a very melodramatic, almost aggressively romantic approach. Very much comprised of one emotive theme throughout, it’s too repetitious to be considered one of his best Hitchcock scores, but certainly adds to the odd effect of the film. The musical highlight is probably the hunt sequence where very English hunt music turns into a nightmarish variant of Marnie’s theme. Marnie is an endlessly fascinating picture, maybe contradictory in some aspects, but a film that seems more complex and adult with each viewing, reduced to its simplest level being basically about one’s search for love and acceptance, but totally avoiding mawkishness. Take the final scenes. Marnie and her mother make make some kind of peace, but whereas most films, even now, would have the two embrace each other with declarations of love, this one stops well short of that. The healing has begun, but it’s going to take as a while. And as for Mark and Marnie….well, as they leave Bernice’s house and drive off, it’s possible that Marnie’s troubles could just be beginning.

Excellent review. You should read it Suzanne Lucas, John David Griffiths and Richard Griffiths.