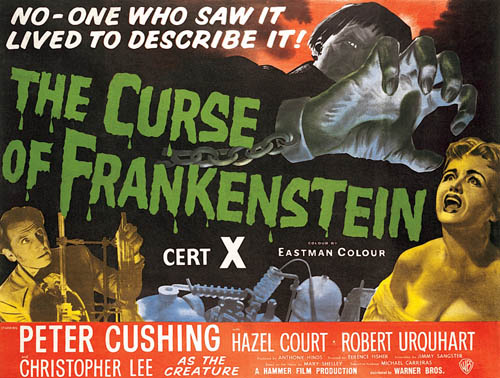

The Curse Of Frankenstein (1957)

Directed by: Terence Fisher

Written by: Jimmy Sangster, Mary Shelley

Starring: Christopher Lee, Hazel Court, Peter Cushing, Robert Urquhart

UK

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME:82 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Baron Victor Frankenstein is in a prison cell awaiting execution for murder. He tells the story of his life to a priest, beginning in his youth when the death of his mother leaves him in sole control of the Frankenstein estate. He engages a man named Paul Krempe to tutor him, but after two years of intense study, Victor has learned all that Paul can teach him, and the two begin to collaborate on scientific experiments. One night, after a successful experiment in which they bring a dead dog back to life, Victor suggests that they create a human life from scratch. Paul aids him at first, but eventually withdraws, unable to tolerate the scavenging of human remains which continues despite the arrival of Victor’s cousin and fiancée Elizabeth who has come to stay….

Though The Quatermass Experiment was undoubtedly the first horror film to come from Hammer, it was The Curse Of Frankenstein which really began Hammer Horror as we know it, setting the style for what was to continue and become a world famous brand, and already with pretty much all the key crew in place. In some respects, it’s a little awkward in places and the aspects which would define Hammer Horror would be refined in the films to come. Despite the glorious sets, the low budget means that it’s a very claustrophobic, even slightly cramped, picture with just a few characters and locations, though this at times works for the film as much as it does against it, coming across as an intelligently distilled, stage-like condensing of the famous story, with the emphasis now on creator rather than monster. It’s hard for a modern viewer to really appreciate how much of a sensation it was, because we’re now used to our horror films being much more graphic, but prior to 1957 films like this would never dream of showing severed body parts or a graphic face shooting, and in colour too! There wouldn’t have been many before with such a ruthless, unscrupulous anti-hero at its core too. I suppose one flaw with the film is that it’s hard to know who to root for, but that helps give it a very cynical, almost modern edge.

Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg, who went on to create Hammer’s main rival Amicus Films, took a script to Hammer called Frankenstein And The Monster, to star Boris Karloff, but Universal objected, threatening a lawsuit if there were any similarities to their Frankenstein films. The large scale adaptation of Shelley’s book was far too expensive for Hammer, so they paid Subotsky and Rosenberg off and got Jimmy Sangster to write a totally new screenplay which would be cheap to film and which Warner Bros. would be happy to co-fund. Christopher Lee beat out Bernard Bresslaw for the part of the Creature because his fee was £2 less a day, while co-star Peter Cushing asked to play Frankenstein because he loved the 1931 film. They had actually been in two previous films together but never met before. Their friendship was sparked when Lee stormed into Cushing’s dressing room, complaining that “I’ve got no lines!” Cushing responded, “You’re lucky. I’ve read the script.” Shooting fell behind schedule and some scenes involving young Frankenstein and young Elisabeth were cut from the script. Hammer initially showed the BBFC a black and white version so there would be less cuts, and the BBFC only wanted the dissolving of a head to be cut [stills survive of this], but Hammer were then asked to submit a colour print, though they cheekily did it just a couple of weeks before the release date so major alterations couldn’t be made. Aside from the close-up of an eyeball which remained in US prints, they were only asked to shorten certain gory shots, not remove them entirely. Despite being released to critical revulsion, the public flocked to the film, and Warner released it to great success [often double billed with Quatermass 2] in the US too. It held the distinction of being the most profitable film to be produced in England by a British studio for eleven years.

After the appropriately Gothic titles against a smokey red background, The Curse Of Frankenstein opens unusually with Frankenstein in a prison cell relating his story to a priest before he’s executed for murders, something which was the only major thing used from the Subotsky and Rosenberg script. In a film which gives brilliant entrances to both Cushing and Lee, Cushing is first seen as a shadow in the corner of his cell from which his human form seems to step out. He begins to tell of his background, and I must warn first-time viewers of this classic is that it’s around three-fifths of the way through before the ‘Creature’ [I guess Universal objected to the word ‘Monster’ ] wakes up. The first part of the film is shot very statically and proceeds at a very measured pace, while the second half sees the camera move much more and the editing become quicker. Much of the emphasis is on Victor getting the various parts he needs for his creation, and this Frankenstein isn’t above murder to get a decent brain, but, in a variant on the 1931 Frankenstein, it becomes damaged in a struggle with Paul Krempe, the teacher who becomes his assistant and then decides he doesn’t want any part of it all. Small wonder, then, that the first thing the Creature [who is actually brought to life by an act of God rather than Victor] does is to try to strangle its creator. What an entrance Lee has in this film! Victor runs out of his lab for help and later runs back in with Paul, the camera tracking fast through the doorway towards a bandaged giant looming menacingly in the lab, eventually ripping off the bandages covering his face as the camera tracks in quickly again to reveal an almost impossibly hideous visage beneath.

Phil Leakey’s makeup, which was done at the last minute out of cotton, rubber and mortician’s wax directly onto Lee’s face after earlier designs didn’t come off, may not be iconic in the way Jack Pierce’s is in the Universal films, but it’s far closer to Shelley’s description of her monster and also more believable as something basically sewn together from body parts. Lee’s unsettling performance, with his puppet-like walk and jerky reactions, has I feel been undervalued. It’s extremely detailed to the effect where, while this Creature is constantly unfriendly and frightening, you do feel just a small amount of pity for this wretched thing, a thing which seems to be in agonising pain. There’s a superbly photographed sequence involving the murderous Creature which takes us outside to a neighbouring wood [not the soon to be overly familiar Black Park!], but the two primary set pieces of the final third are two splendidly suspenseful scenes of the two female leads going where they shouldn’t and putting themselves in peril, superbly handled by director Terence Fisher. When Hazel Court or Valarie Gaunt are getting closer and closer to where the Creature may be and James Bernard’s scoring evokes tremendous dread, you’re almost getting to the essence of Gothic horror, especially when, despite what many aghast reviewers at the time thought, Fisher employs such classical devices as the Nosferatu-like shadow of the Creature’s hand and face looming from the side of the frame. Oddly, the Creature is never seen to actually kill his victims either [nor does Elisabeth ever see him], and we don’t even see the bodies of the old blind man and young boy he murders! It seems that you’ve watched a very brutal film when it finishes, but you haven’t really.

The severed eye balls, severed hands and brains don’t seem shocking these days and we hardly see any actual surgery, though the Creature spurting blood after being shot in the face is still startling. Despite the low budget, which aside from the film’s restricted settings only really badly affects a party scene which lasts a few seconds and features just a few people, the sets and costumes are lavish. Set designer Bernard Robinson works wonders with the rooms at Hammer’s Bray Studios which was actually a large country house, while the laboratory certainly looks like it could be authentic with its Victorian-seeming bric-a-brac and, despite the immense clutter some of the scenes there, they’re shot in almost impressionistic patterns of yellow and green. The most striking thing about the film though remains its presentation of its title character, meticulously played by Cushing [and yes, he looks into a magnifying glass for the first time in this film hurrah!] mixing cold-bloodedness with elegant charm, though his matter-of-fact responses to problems are rather amusing. This Frankenstein is a dandy, always meticulously clothed as he moves from laboratory to drawing room, but he’s also totally obsessed by his work [reviving the Creature twice] and entirely devoid of moral scruples, killing an old professor for his brain and sending the maid whom he’s got pregnant to where the Creature is residing while totally ignoring his fiancée. Any moral dimension is brought by Paul, though I feel the movie would be stronger without him having obvious feelings for Elisabeth and her fate being different, while Victor’s plea for mercy seems out of place for the character. Hammer weren’t quite ready to go as far with their material as they could have done, but then they had just reinvented themselves!

Hazel Court, later to appear to three of the Roger Corman/Edgar Allan Poe pictures, exudes glamour and looks stunning in some outfits worthy of Grace Kelly. Her young daughter played her character as a little girl. Andrew Leigh has a tiny cameo as a drink-loving Burgomaster who provides a chuckle. Bernard’s truly menacing score, with its effective use of dissonant chords, is largely based around two motifs which are often allowed to build and build. He generally had little time to write his scores, which is why they’re often simply constructed, but they would go on to define the Hammer sound. The Curse Of Frankenstein can’t help but be a little static, and compared to how it would be made today it seems positively restrained, while at least two of Hammer’s successive Frankenstein films would be better – in fact, I could name at least fifteen Hammer films I think are superior. One could say that the Hammer style wasn’t actually perfected until Dracula, The Curse Of Frankenstein being more of a try-out. Nonetheless, it remains a vivid, often extremely tense movie which still impresses with its bravura and its two brilliant main performances. And one could say that this little, small-scale movie changed the face of the horror film forever and was the most important film for some time to come along in the genre until Psycho came out a few years later.

Rating:

Be the first to comment