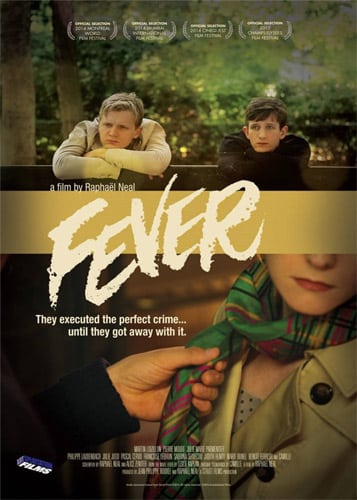

Fever (2014)

Directed by: Raphaël Neal

Written by: Leslie Kaplan, Raphaël Neal

Starring: Julie-Marie Parmentier, Martin Loizillon, Pierre Moure

After festival screenings in 2014 Fever was released by Artsploitation Films in May 2016.

The DVD release can be found here and for details on the film itself please see their site.

Fever is a French crime story (not to be confused with the German drama directed Elfi Mikesch) about two young boys studying literature and philosophy who, in the opening seconds of the film, have murdered a woman in her apartment. This happens off screen with just a few sounds of the death being heard. This impersonal act starts the whole thing moving and gets to the core themes of a story in where they have decided that without motive, without even knowing the victim, it’s not really a crime at all. Getting away with something like this has come up in thrillers of the past, like Hitchcock’s classic Strangers on a Train; but this premise and the way it begins might have more in common with Rope with its intellectual duo of killers. But to sell this as a suspense thriller or even a straightforward murder mystery would be incorrect, and this jumping off point is used to take the plot into a more unusual direction.

The title of the film, and the song it refers to, suggest this is going to be a slow burning drama, but pacing aside it’s a decidedly chilly affair. There’s a great sense of unease running through the story, which is aided by the desaturated colour scheme. The score also includes some eerie vocals which are accompanied by a few moments of sparse percussion along the way. This is in contrast to the locations on offer with their stylish Parisian streets and the human warmth of restaurants and homes which the two leads spend much of their time in. It soon becomes apparent they the pair have done this simply because they could, not because of any social problems or difficult upbringings.

They do their homework and eat out, and this sense of normality becomes ever more awkward as the weight of the deed becomes heavier on their minds. Initially Damien (Martin Loizillon) is the more confident of the two and shows all the bravado. He has more disrespect for his family than his friend Pierre (Pierre Moure) who is more reserved and shows the first signs of a guilty conscience. The dual nature of their personalities is given a lot of time and to keep things interesting their roles do not stay fixed as things progress. It’s not a unique character dynamic and is perhaps predictable, but it’s still compelling.

The growing strain on their friendship isn’t helped when they realise a glove was lost outside the crime scene and there are later police reports of DNA under the victim’s fingernails. The growing suspicion of Zoé (Julie-Marie Parmentier) who was working at the opticians across the street from the location is also a problem for them. In a standard thriller plot all this would lead into mounting tensions, police action and a slow descent into paranoia as things unravel and the walls start to close in. But it’s here the story starts to take a more unusual approach to the subject matter and the character drama becomes something unexpected.

While there are some suggestions that Pierre’s potential romantic interest will threaten to strain his friendship with Damien this is soon cut off by the second act, which sees them taking time off for study during the summer. The growing shadow of their individual family heritage during the Second World War becomes a plot element when Pierre begins to suspect one of his relatives may have been a Vichy government administrator, and a Nazi collaborator. This begins a new tangent that is a surprise but as a result feels like it comes out of nowhere. The suspense atmosphere from the opening is drained away and replaced by something that is thought provoking, but not entirely effective.

Meanwhile Zoé realises what has happened but finds herself unable to act on the possible evidence she has found, instead obsessing over the murder and finding her own domestic situation coming under pressure. This kind of meditation on the nature of evil and whether those who act (or do not act) in immoral situations is at least an interesting element to add. The possibility of having to live with this knowledge or the idea that getting away with a crime is worse than confessing offers plenty of food for thought. But this is in conflict with the other plot strands which have been woven in since the beginning, and the lack of standard procedural elements mean it lacks drama. Which is particularly true when so much time is spent in the optometry store or with Zoé’s own romantic relationship.

While there are certainly a few tense moments in the climax the pacing and focus of the narrative is often far too cold and distant, much like it’s two central characters. Personal crises are reached and big questions are asked, but it never builds a real sense of urgency. Rather than ever threatening to boil over it just sort of simmers for most of the duration. It’s a story which will certainly make you think about these themes after the drama concludes, but don’t expect any kind of immediate gratification when the credits roll. It’s interesting enough on the whole but perhaps a few more conventional ingredients here and there might have helped.

Rating:

Be the first to comment