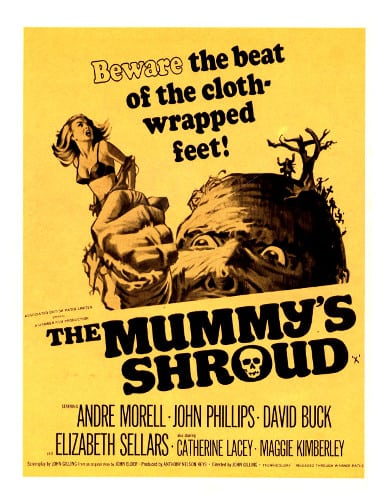

The Mummy's Shroud (1967)

Directed by: John Gilling

Written by: Anthony Hinds, John Gilling

Starring: André Morell, David Buck, Elizabeth Sellars, John Phillips

UK

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY AND DVD

RUNNING TIME: 91 min

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Ancient Egypt: Prem, a manservant of the boy prince Kah-To-Bey, spirits away the boy into the desert when his father the Pharoah Men-Ta is killed in a coup, but Kah-To-Bey dies and is buried. 1920: an expedition led by scientist Sir Basil Walden and businessman Stanley Preston has already unearthed the mummy of Prem and, ignoring a warning issued to them by local Bedouin Hasmid about the consequences for those that violate the tombs of Ancient Egypt and remove the bodies and the sacred shroud, soon finds Kah-To-Bey too. When Sir Basil is wounded by a snake just after finding the tomb, Preston commits him to an insane asylum to take credit for finding the tomb and the mummy himself. Meanwhile, after being placed in the Cairo Museum, the mummy of Prem is revived when Hasmid chants the sacred oath on the shroud….

I had to chuckle when I looked at my copy of The Mummy’s Shroud and noticed it was a ‘PG’ , but then come to think of it so is Hammer’s The Mummy. It’s a little surprising considering there are some vicious killings in it. One thing I really like about these Hammer Mummy films as opposed to the Universal ones is that the victims tend to be killed off in a variety of ways as opposed to just strangulation – they really are proto-slasher movies. Existing somewhere between The Mummy and The Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb in quality, The Mummy’s Shroud, even if it seems to derive a few ideas from the Tutankhuman affair, seems very constrained by its almost threadbare scenario which lacks the romantic aspects of the 1959 film and the crowded – if confused – plotting of the 1964 one. It’s not really about anything else than the Mummy killing just a few people, and that’s not really enough for a film which is around an hour and a half and rather longer than the Universals which tended to move pretty fast. It’s partly compensated for by some interesting human characters including possibly Michael Ripper’s greatest ever part for Hammer, more visual invention than director John Gilling usually went for, and some of Hammer’s best Mummy set pieces. It fails to rise above ‘B’ status, but certainly has its pleasures.

Producer Anthony Hinds wrote an outline which was turned into a script by Gilling in just five days for what was another film in the eleven picture deal Hammer struck with 2oth Century Fox in connection with their long-time partners Seven Arts. John Richardson was originally cast as Stanley’s son Paul, but for some reason was replaced by David Buck just a couple of days before shooting. While Dickie Owen, who had played the bandaged fiend in Hammer’s previous mummy picture, reappeared in this one as Prem in the opening flashback, it was stuntman and Christopher Lee’s double Eddie Powell who played Prem’s reanimated self. His appearance, different to the way most other movie mummies look with smaller bandages and shrouds, was based by makeup man Geroge Partleton [Roy Ashton had just left the studio] on a genuine mummy in the British Museum, as was Kah-To-Bey – and I actually visited the place a year or so ago and thought I recognised them from a particular Mummy film or films but couldn’t place them! Filmed mostly in Bray with just one day spent shooting in a nearby quarry at Wapsey’s Wood, Gerrards Cross, The Mummy’s Shroud turned out to be the studio’s last picture to be shot there aside from special effects footage for Moon Zero Two and When Dinosaurs Ruled The Earth. Stills exist of Andre Morell having gruesome makeup being applied to his head for a scene where his character’s bonce is crushed to a pulp by Prem, but the shot was removed from the finished print and seemingly without the BBCF requesting it. Reviews were pretty withering, but the double bill with Frankenstein Created Woman did good business.

The usual flashback here opens the film, as a narrator tells a story over some reasonably convincing Ancient Egyptian paintings which become some not-so-convincing sets. Now I’ve always thought that it was Peter Cushing whose voice we hear, as it really does sound like him [unlike his Rogue One impersonator], but actually it’s a guy called Tim Turner. I wouldn’t be surprised if Cushing was unavailable and Hammer chose Turner to do it because of how similar his voice sounded. The flashback moves to the quarry and it’s rather obvious that all the desert scenes in this film were filmed in a small area of what is basically a sand pit, with no shots without any hilly surroundings. Fast forward to 1920 and we meet one of the most unpleasant characters in Hammer; the lazy, devious, lying, self-centred and arrogant businessman and financier of the exploration Stanley Preston. He reluctantly joins one of the search parties and finds the main expedition which was deemed lost, but then just lounges around while the others work, yet dictates his servant Longbarrow to type that he works endlessly in an environment of near mutiny. It’s Longbarrow who’s the character played by Ripper, and the actor manages to turn what could have been a very dislikeable weasel of a human being into a downtrodden guy you feel rather sorry for despite his bizarre dedication to a master who treats him like crap. In terms of the actual explorers the most intriguing character is surprisingly [but then Hammer were starting to provide more interesting female roles] a woman. Despite Hammer’s usual beefcake publicity shots of actress Maggie Kimberley being menaced by the Mummy with her tits virtually falling out of her top, Claire de Sangre, who seems able to accurately prophesise, is intelligent and even refuses to read out aloud the usual scroll that resurrects the Mummy, the first Mummy movie character to have such a scroll and not do the obvious!

The idea of a dynasty of protectors of the tomb comes from Universal, while we again have a character committed to an asylum – though this time so that Preston can take credit for and have everything. Basil Walden manages to escape off screen and finds himself in the home of gypsy fortune teller Haiti who turns out to be Hasmid’s mother, a home which is shot with wide angle lenses and red lighting so it’s rather unsettling. It’s these two who resurrect the Mummy –there’s a rather startling close-up of his eyes cracking open – and they do so just after half way through the film which means we have to get through lots of chatter in hotel rooms, though it’s earlier than in The Curse Of The Mummy’s Tomb where the star of the show only wakes up when two thirds of the movie have passed. The desecrators begin to be killed off and as usual the local police inspector is slower on the uptake than everyone else, though the film resists the temptation to make a fool of the character and he even plays a major part in the climax, a sequence which is is a little rushed and disappointing, However, it does contain one of Les Bowie’s most striking special effects moments as Prem claws away at his disintegrating head. His assistant’s hands crumbled a dummy wax head filled with fuller’s earth and paint dust atop a prop skeleton, and it took a month’s worth of tries to get the sequence right.

The Mummy’s Shroud lacks the humour that appeared every now and again in the previous two Mummy pictures, except for a moment where somebody gets something out of a cupboard and doesn’t notice the dead body hanging there. There’s an interesting theme of sight, whereupon the female characters, even Preston’s long suffering wife Barbara who nonetheless sees her husband for what he is, see far more than the male characters. The four murder scenes – all of men – all have the Mummy only partially glimpsed by the victims [and in two cases seen as a reflection in something] – and this is taken to extremes when Longbarrow drops and breaks his glasses so the Mummy appears distorted to him when he comes to wrap him in bedding and throw him out of a window. Then there’s the crushed head that was cut but is compensated for by gruesome sound effects, photographic acid in the face, and a head bloodily bashed against a wall. Only one of these shows any blood and it’s all done with some restraint, but the staging of these scenes still makes them come across as shockingly brutal as well as allowing Gilling to provide some slightly more offbeat visuals than he normally came up with. It also helps to atone for the fact that this Mummy, even though based on a real one, doesn’t look very impressive. On the other hand the preserved body of Prem looks disturbingly realistic. Bernard Robinson does his usual good work on the hotel room interiors which is just as well as this, despite occasional use of a limited street set, must be the most ‘indoor’ Mummy film ever made, helping to give it a rather claustrophobic feel which I must admit isn’t detrimental to the picture.

Despite a cast which all performs well – I haven’t yet mentioned David Buck who projects more personality than the usual Hammer young ‘hero’ and Elizabeth Sellers as Barbara Preston Stanley’s put-upon wife – it’s Catherine Lacey as Haiti who really stands out, helping to make the gypsy a quite unnerving character with her weird looks and odd pronounciation of some words, though even she can’t make convincing Haiti’s inexplicable change of sides near the end. Composer Don Banks contributes a simpler, more straight forward score than his previous two, with lots of quite conventional suspense work, though he employs Middle Eastern chord and note structures sometimes and his choral main theme is manages to be enjoyably bombastic yet slightly mysterious at the same time. The Mummy’s Shroud sometimes tries very hard to transcend its limitations, though taken as a whole it’s a solid but unremarkable effort from Hammer.

Be the first to comment