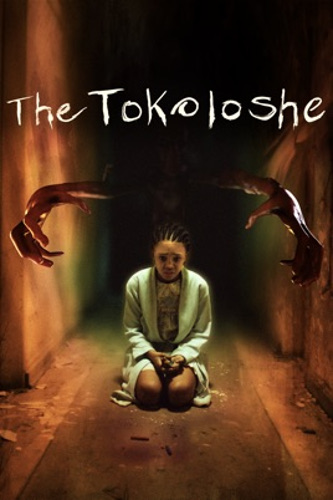

The Tokoloshe (2018)

Directed by: Jerome Pikwane

Written by: Jerome Pikwane, Richard Kunzmann

Starring: Dawid Minnaar, Harriet Manamela, Kwande Nkosi, Petronella Tshuma

SOUTH AFRICA

AVAILABLE ON REGION 2 DIGITAL PLATFORMS from EVOLUTIONARY FILMS, REGION 1 DIGITAL PLATFORMS AND DVD from UNCORK’D ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 91 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera, Official HCF Critic

Busi has moved to Johannesburg to escape a traumatic existence in her rural childhood home, and takes a job cleaning a hospital at night, hoping to earn enough money to bring her sister to the city. But Busi has to deal with her boss Ruatomin expecting certain ‘favours’, indifferent staff, and a hospital that, under budget cuts, is only half-operating. After overhearing a demonic voice threatening the voice of a young girl, she comes across little Gracie, who’s been abandoned in the hospital. She believes she’s being tormented by a tokoloshe, a creature that insists that it plays with her but who keeps on playing rough. Busi doesn’t see anything that’s proof despite being increasingly spooked by the place, but then how do you explain those scratches on Gracie’s shoulders….

So what is a tokoloshe? I had no idea either, but a minute’s worth of research told me that it’s sort of the Zulu equivalent of the Japanese kappa; a small but malevolent creature. This water sprite is often conjured up to cause trouble for others. At its least harmful, a tokoloshe can be used to scare children, but its power extends to causing illness or even death. They especially like to bite the toes off sleeping people, which could be why Zulus often slept in raised beds, and appear to be sighted by prepubescent girls more than any other age type of person. There’s apparently been only one feature length film concerning this creature, 2013’s Ghetto Goblin [aka Blood Tokoloshe], which isn’t generally considered to be much good. Knowing very little about African legends and always finding folklore of other cultures to be of considerable interest, this was enough for me to check out this 2018 effort from South Africa, the title of which my eyes alighted upon when deciding which of the many digital screeners on our never ending list to do next. And I was most glad that I did so, once I realised that [and this will undoubtedly disappoint some], the title thing isn’t much of a physical presence. However, it’s very much a metaphorical presence, tied in to the depiction of a society where, unfortunately, women are still often oppressed and the proportion of domestic violence is one of the highest in the world. I think that even Dr Lenera, despite often whinging about all this ‘woke’ stuff that’s taking over movies, can avoid his usual ranting on the subject when dealing with a film that takes place in an environment which is so genuinely unpleasant for many females in real life.

It’s superficially similar to Under The Shadow, with another woman living in a society that treats her terribly facing a demon which partly represents one kind of this oppression for the protection of a child, though to me Jerome Pikwane’s directorial debut seems closer to The Badabook in more than one way. He unashamedly wears the influences of others on his sleeve too, while some of the scares will be ones that you’ve seen over and over again, especially recently when so many horror films just seem content to rehash the same devices. Yet somehow The Tokoloshe still manages to be quite frightening in parts, something that, when you’ve seen so much horror for several decades like me and have therefore gotten awfully jaded, instantly makes a horror film worthy of some respect even if there isn’t much else good to be found about it. Fellow HCF critic Ross Hughes likes to use the term “got my horror juices flowing”, and that’s certainly what one particular scene in this film did to me, sending some beautiful chills down my entire body, when its heroine was on the phone in the foreground and in the background the little girl, unnoticed by the woman only a few feet away from her,began to communicate with this demonic thing, that’s been tormenting her. The monster remains hidden except for an arm we can just about glimpse behind a filthy window, after which we track both characters around the house together in a particularly virtuoso piece of film-making from Pikwane, somebody I hope we’ll be hearing more from in this genre in the future. Despite his often good staging, the main reason much of the film works so well might be because of the sheer amount of darkness in it, its characters inhabiting a world in which black is the dominant colour, a colour that’s always surrounding them, almost crushing them, giving them no escape. I almost wish that I could see it in black and white.

The sight of a woman running in terror in a field from something is the first shot that we see – and she really does look frightened. She stops as she nears a house, then is pulled off the left hand side of the screen. Is this the first of several dreams by Busi that are also flashbacks, or just a dream? Some brief background about the tokoloshe then plays over animated title images of stick people and a demon, and it’s interesting that, when we see some similar drawings on a wall much later, they aren’t dwelt on, there aren’t even any lines of dialogue “explaining” them to the viewer; as with some instances elsewhere, Pikwane and his co-writer Richard Kunzmann credit us with enough intelligence to work things out, though I guess that, immediately after the opening titles, us hearing on the radio news of Johannesburg being filled with immigrants who live in terrible conditions was felt necessary clarification for non-South African viewers who may not otherwise pick up on this. Busi arrives at her new job, and by god this hospital is a grim setting; dark, dirty, and with more staff than patients. “Welcome to the night shift”, says Ruatomin the manager with almost lip-smacking relish, before telling Busi that her kind “are all trouble” because they keep leaving. Of course we can already guess why, and the only other nurse tells her to stay out away from Ruatomin. Busi wants to make enough money so that her sister can come to live with her, and slightly more information regarding their background is revealed with each dream of Busi’s that give us quick cuts to images which gradually form a picture, and an upsetting one too, though I will say right now that it’s a picture that’s never entirely clear by the end; we have to complete it ourselves. However, the present day is no better; Busi finds the place extremely spooky as would you and I, she accidentally locks herself in a store room, and not just Ruatomin but Busi’s landlord tries to get sex from her because she’s behind with her rent.

The real and the supernatural are frequently linked together, as if each is making more sense of the other. Busi goes in for a shift and we see Ruotamin lurking in the darkness, but Busi is preoccupied by this little thing that she thinks she sees. We have something running in front of the camera, a device rather overused, and soon after that see what looks like a child wearing a hideous mask sitting down, though we’re not sure. Rusi follows it into one of the wards and bumps into a boy with the mask placed on a bed, so it was all a false scare, but surely when Rusi overhears a monstrous voice telling a girl to do something that can’t be false, can it? Pikwane keeps the tokoloshe virtually hidden, yet we’re still rather scared of it when young Gracie is. This is largely because, of course, she’s a child, and it’s usually scarier when a child is in fear than an adult. Compare for example the flashback scenes of horror to the ‘present day’ ones in The Haunting Of Hill House; there were definitely some shivers and frights to be found in the latter, but the comparable scenes in the former packed a far stronger punch. Kwande Nkosi acts fright more convincingly than any child performer I’ve seen in ages, though of course Petronella Tshuma matches her and the two make a great pairing. But, in another choice that may frustrate some, we never find out anything about Gracie; she remains just another abandoned child to whom Busi can act as a surrogate mother. Seeing as Ruotamin has docked her pay because her uniform was torn when he tried to rape her, and that something does indeed some to be around, Busi decides to take her and Gracie away from the hospital, but will they be safe from either?

To balance out its nasty male characters, we have a polite though cold technician and more importantly the character of Abel, a blind modern day witch doctor with an extensive collection of masks on his wall. He befriends Busi on the bus when she can’t pay the driver, and ends up giving her a mask which is supposed to be magical, though said mask rather laughably doesn’t prove to be of any help; all it does is have its eyes glow and then break. It’s as if Pikwane and Kunzmann really wanted to give us a sympathetic man, and fair play to them, but then didn’t know what to do with the character they created, leaving us with enticing hints of a deeper exploration of the local mythology which fails to happen. However, the merging of the literal and the symbolic, despite being fairly obvious, is usually done pretty well, and I almost wish that the film had remained ambiguous about its creature, a creature that could have been a manifestation of the fear of its two main female characters as well as maybe a few other things too. But – and I’m giving this away just so that those who want to see the monster know that they will be eventually rewarded [if that’s the right word] – towards the end the not too obvious becomes the obvious. This in itself wouldn’t be too bad a thing if the creature had looked good, but, while the Pumpkinhead-like design is alright even though not resembling much what a tokoloke probably should look like, the CGI is dreadful even though you only see the creature briefly. Yet again, I ask the question – why go down the digital route if you don’t have the money to successfully achieve things? The film then seems to end very suddenly with not everything resolved, including a mother/daughter relationship that’s introduced late in the day but which does immediately involve us. But then, sometimes that’s life.

The Tokoloshe takes place in a world of sexual threat, violation and trauma; even when the monster attacks Grace in bed in an exceedingly uncomfortable scene, there’s something horribly sexual about it. This doesn’t always make this film the easiest of watches despite not actually containing any graphic rape footage, and some may find it rather crass, but at least there’s no out of place humour, and this does ram home how horrible the world in which the characters live is, and a world in which it’s shown that it’s not entirely the white people who are to blame, another example where Pikwane and Kunzmann deviate just a little from the path most Hollywood film-makers of today would have gone down. Trevor A. Brown’s cinematography is very good seeing as this is a fairly cheap digitally shot production, and that the main colour palettes are black or brown, with a bit more of the former. There are some nice shots, like a face looming out of the dark, and some lengthy tracks around interiors and down corridors which sometimes recall The Shining’s steadicam work. A favourite device of Pikwane is for scene transitions to be black for a few seconds whether lights are going or not, leaving us feeling just like his main characters are. Of course many of the scares will be familiar, like a ‘something under the bed sheet’ bit which we’ve already seen in Under The Shadow, The Grudge and others, and yet another red ball being bounced about, though there are actually very few jump scares, Pikwane preferring to rely more on mood. All in all I think that, despite his film containing a slightly disappointing final third, Pikwane has a real feel for the genre as well as an ability to mix it with social commentary like Jordan Peele did [though without his humour] with Get Out – though let’s hope that his follow-up film is no Us.

Be the first to comment