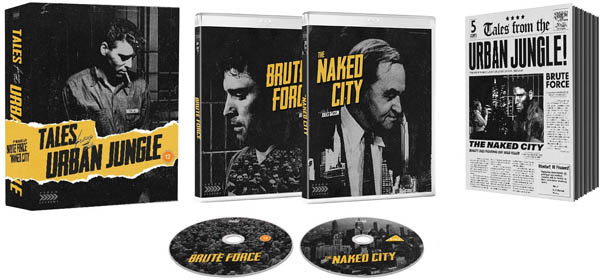

Brute Force, The Naked City (1947, 1948)

Directed by: Jules Dassin

Written by: Richard Brooks, Robert Patterson

Starring: Barry Fitzgerald, Burt Lancaster, Charles Bickford, Dorothy Hart, Howard Duff, Hume Cronyn

TALES FROM THE URBAN JUNGLE – BRUTE FORCE [1947/ THE NAKED CITY [1948]: On Blu-ray 29th March, from ARROW ACADEMY

The name of Jules Dassin first came to my attention with a TV showing of the stunning and highly influential heist thriller Rififi, though being a movie maniac means that one doesn’t always get around to checking out all the movies that you intend to, so I didn’t go on to explore his resume. However, Arrow Academy have come the rescue with this great-looking package of two Dassin films which pairs together two earlier releases but also upgrades them…..

DISC ONE – BRUTE FORCE [1947]

RUNNING TIME: 98 mins

Westgate Prison is supposedly ran by Warden A. J. Barnes, who’s under pressure from outside to be tougher on his unruly inmates, though it’s really Capt. Munsey, who wants Barnes’s job, who calls the shots. Munsey manipulates prisoners to inform on one another and create trouble so he can inflict punishment both psychological and physical. Joe Collins returns from his term in solitary confinement and wants to escape. When another prisoner is provoked into suicide by Munsey, this gives the higher authorities the opportunity to revoke all prisoner privileges and cancel parole hearings – and give Joe more aides in planning an escape….

Twelve years before he became The Birdman Of Alcatraz, Burt Lancaster was incarcerated in another movie jail, one of many prisoners who aave to dig this tunnel which his entirely pointless except maybe in symbolic terms. In many ways it’s more conventional, the searing prison drama containing many ingredients that were probably tried and tested even at the time. However, it really surprises with its bleakness and its despair in what seems to be a flat-out attack on not just the prison system but the world and society itself. It’s a vicious punch to the stomach of a film which suggests that life is an unfairly rigged system and the only meaningful act is rebellion. One wonders how on earth producer Mark Hellinger and Jules Dassin managed to get it made under the rigidity of the Production Code at the time when tamer films had to be censored; we have negative depictions of authority and law enforcement officers, brutal violence, a prison captain who looks he gets sexual release from torturing prisoners, and a seeming backing of revolt against law and order. There isn’t even any religion to offset the strong material, and therefore no sense of redemption. Yet I hope I haven’t made Brute Force sound overly depressing, because it oddly isn’t; its expression of rage, in a world where perhaps brute force is the most important thing, is rather liberating. It’s a 1940’s film, so it doesn’t make any of its prisoners seem particularly bad, while some flashbacks smack of so-called ‘women’s interest’ even if for me they enhance the fatalism, the idea that the cards will always be stacked against you. Yet towards the end it virtually becomes a film from the latter half of the ‘60s.

The titles occur over the shots of the prison which is joined to an island by a long bridge, and the mattes and miniatures that create this fictional location are extremely convincing even though we see then; truly excellent work here. Score composer Miklos Rozsa provides one of his archetypal film noir themes which sets an appropriately forceful tone. It’s morning roll call time at the prison, and a group of prisoners cram into a small cell to watch through the window as Joe Collins returns from his term in solitary confinement. He’s not happy. “It’s not okay, and it never will never. Not till we’re out of here”. We don’t exactly what Joe did, but we do know that somebody planted a knife on him, and who this somebody is. The somebody is now very afraid, because, even though he was either coerced or even forced into doing this by Munsey, he knows that something terrible will happen to him in revenge for his act. He’s already being ignored by everyone else, and our sympathies are twisted; it was his doing that contributed to somebody else being punished so we ought to hate him, yet we start to pity him too and become frightened for him as he’s basically just a pawn in a rotten and corrupt system. Meanwhile an official from the governor is demanding more clamping down on the prisoners after what has been a series of bad incidents, though only because it makes the governor look bad. Warden A.J. Barnes doesn’t agree with this, saying that this may result in criminals coming out worse than when they got in, but is considered to be ineffectual and has to obey which Cpt. Munsey is clearly loving. The implication is clear; there’s more interest in control and punishment rather than kindliness and rehabilitation. Munsey sees that he might be able to get Barnes’ job if he stirs and incites among the prisoners. In this fraught and cruel situation, Dr. Walters turns to the booze to help him cope. He has great sympathy for the prisoners and hates the inhumanity with which they’re often treated, but what can he do?

The build-up to the stooge getting it is very tense, a lengthy tracking shot taking up much of a scene where the information ‘Wilson 10.30’ is passed around the prison’s machine workshop. A fight is staged and, as guards come in to stop it and of course just make the brawl bigger, three men corner the poor guy with blowtorches, one of which seers one of his hands, before he steps back in fear into the mouth of some large machine which crushes him. Of course Joe has an abili; he was talking to the doctor all this time. Before this is able to blow over, Munsey tries to get another prisoner to help him and when turned down torments him with the knowledge that both all his letters to his wife have been censored and that she’s filed for a divorce. We don’t know if these things are true or not, but it’s enough to make the poor guy hang himself. Joe presses another inmate, Gallagher, to help him escape. Gallagher has a good job at the prison newspaper and Munsey has promised him parole soon, However, the suicide incident has caused the prison to be much stricter immediately, and one senses that the pressure cooker is eventually going to boil over especially with Munsey’s sadism not abating. Hume Cronyn tended to play weak or ‘nice’ roles, but here, despite not being physically imposing he’s totally convincing as a borderline psychopath who believes in the natural order of the strong controlling the weak, therefore giving him the right to do what he wants to his inmates, and having no conception of right and wrong. His best scene is when he beats a Jewish prisoner with part of a hosepipe in his office while Wagner on the record player drowns out the action. Of course we don’t see bloody detail or even the bar hitting the person, but it’s still very sadistic, while this and him polishing one of his rifle in a vest daringly suggest homosexuality and that sexual frustration could be going on here.

At four instances the narrative flashes back as, spurred on by a picture of a woman that causes some to think about their own loved ones and even consider her to be real because they’re so lonely. This allows Rozsa to include some of his customary sad-flavoured lyricism in a generally dark, grim score. Spencer cheatingly wins loads of money in a gambling hall but when driving home with the girl he’s picked up, she pulls his own gun [that he’d asked to hide in her handbag when police appear] on him and takes both his money and his car. Robert Becker is a soldier in World War 2 Italy visiting his girlfriend when the military police come calling. The girl’s father alerts them to their presence and is shot by her, causing Robert to take the rap. Tom Lizzer embezzled money to buy his dissatisfied wife a fur coat. And Joe is clearly a career criminal who obviously isn’t that bad because he’s in love with a woman in a wheelchair, an obvious [and perhaps even crass by modern standards] device to create sympathy, but if it succeeds does this really matter? These moments were probably put in for the sake of female moviegoers [which I know is a very dated attitude, something which I can prove by saying that my ex-wife loved some totally male-dominated films and didn’t require some romance in order to enjoy a film], though it’s possible to interpret that Brooks decided to get back at this instruction by producer Arthur Hellinger by getting sexist and suggesting that women are the source of all trouble. I wouldn’t be surprised that, if the film were made today, many critics would come over all offended by this implication, though seeing as two of the women are clearly sympathetic characters it seems obvious to me that this is not what Brooks was saying. He’s probably just suggesting that, in the grim no-hope world of Brute Force, love is hardly the answer and is likely to end up with people in the s*** even if intentions are good.

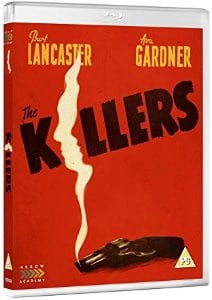

Director Jules Dassin plays some nice games with light, such as the way that characters are often lit from the side, or from underneath, making them look almost surreal. Having recently watched the series of Val Lewton-produced horror films of the ‘40s, I enjoyed seeing Sir Lancelot again as the prisoner who frequently sings to liven spirits including his own. The inmates are almost a Who’s Who of character actors from the period with the likes of Sam Levene, Jeff Corey, Charles McGraw, Vince Barnett, Jay C. Flippen, Frank Puglia, Gene Roth and Glenn Strange being cast to type, some of them carried over from Lancaster’s previous hit The Killers. That film may be slightly superior to this one, but there’s little doubt that Lancaster’s star-making persona is more on view here. His intense physicality means that he constantly seems like he’s about to start punching down walls, while his final moments have considerable power even if we’re not sure if we actually like the person he plays or not; background details are a little vague. His final image, holding a body high in the air atop a tower as fire burns, is as powerful symbol of rage against the machine as I’ve seen. Yet in the end it’s horribly futile [I know this might be a spoiler too many but this is still a ‘40s film and you’ve probably realised how hopeless the world view on display is]. Brute Force is a cracking prison movie that gives you a lot of what you expect and want, but it’s also an astonishingly grim outing that doesn’t seem to believe in justice nor redemption. The world is awful, and “nobody really escapes”, but we need to bloody well try, otherwise what’s the point?

Rating:

High Definition Blu-ray (1080p) presentation of new 4K restoration

Brute Force, as presented here and also on Criterion’s Region A release last September, has a preface attached to it informing us that the original negative is lost while decay, poor handling and messing around with picture and sound by different distributors has damaged the surviving 35mm elements. This restoration is taken from thirteen elements, but you can’t really tell. Sure, some shots don’t look quite as good as others and have a little bit of grain cluster and are a tad softer, but then you’d probably expect that from a film of this vintage anyway. Generally this is a very fine presentation with deep blacks and rich detail.

Original uncompressed mono 1.0 audio

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

Brand new commentary by historian and critic Josh Nelson

This release adds three new special features to Arrow’s 2014 release. The Criterion had a different commentary and two featurettes though it seems like the ones that Arrow offer are superior. Nelson teaches and specialises in “screen representation of violence, trauma and masculinity” so sounds perfect to do a commentary on Brute Force which he says is partly about “the unmasking of the American Dream”. And perfect he turns out to be too, provided a dense and detailed track continually enlightening us about things that are on the screen in front of us as well as what was happening behind it, and I came away with a hell of a lot. I never noticed, for example, that so much of the early imagery and events foreshadow imagery and events in the climax, while we learn that cinematographer William H. Daniels had got a reputation as an alcoholic by the time Dassin asked, against the wishes of others including Hellinger, him to do this film; Hellinger had him constantly followed but he never touched a drop. We’re also told that the MPAA had problems and the torture scene among others had to be heavily re-edited; frankly it’s still very powerful and I’m still surprised that they got away with as much as they did. Apparently Dassin didn’t like the flashbacks, nor does Nelson. There’s a lot to take in here, but things never get too dry. Excellent.

Nothing’s Okay, a brand new visual essay by film historians David Cairns & Fiona Watson [24 mins]

I’ve gotten very used to the relaxing tones of Cairns on Blu-ray releases from Arrow and Eureka. Here, as is sometimes the case, he’s joined by Fiona Watson in what is a quite thorough look at Brute Force despite not being that long [though slightly longer than usual. There’s surprisingly little overlap with the commentary. We’re reminded that Munsey and his lot are very much like Nazis, that the film was brave in having a gay character though dated in that homosexuality is still though of as something wrong, and told that Dassin, when asked about why he initially specialised in comedies, replied, “I specialised in shit”. We also see a still of some eye poking that was no doubt lost due to the censors. Cairns doesn’t like the flashbacks much either. Does anyone except me like them?

Josh Olson: Brute Force, a personal appreciation by the Academy Award winning screenwriter of A History of Violence [6 mins]

Olson tells of his love for Brute Force to which he was introduced to by his grandmother who’s favourite film it was and who is up there “wishing all of us a little Brute Force in our lives”. He comments on director, writer and likes the flashbacks. Yes!

Burt Lancaster: The Film Noir Years, an in-depth look at Burt Lancaster’s early career by Kate Buford, author of Burt Lancaster: An American Life [38 mins]

Buford goes through some of the life and career of the acrobat who ended up having much more control over his own career than most other Hollywood stars. He was spotted in a lift by a scout looking for people to be in a play, and the rest in history. The early films are covered, as is Lancaster’s relationship with The House of Un-American Activities Committee. He spoke out against what it was doing, and the FBI did watch him, but McCarthy and his lot generally didn’t go after big stars, so nothing happened to him. Interesting how his production company did so well for such a long time, then was sunk by the failure of just one film, The Sweet Smell Of Success.

Theatrical Trailers

Image Gallery

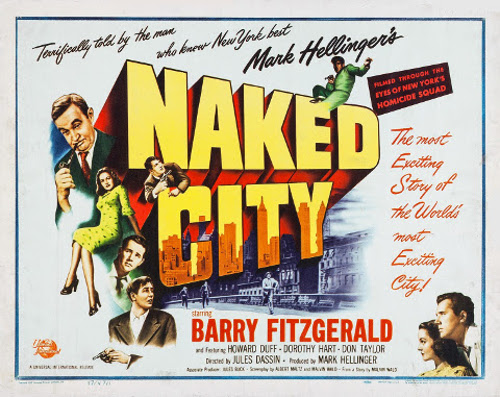

THE NAKED CITY [1948]

RUNNING TIME: 96 mins

In New York at night two men kill ex-model Jean Dexter. When one of the murderers gets conscience-stricken while drunk, the other kills him and throws his body into the East River. Experienced Homicide Detective Lt. Dan Muldoon and his young associate, Det. Jimmy Halloran, are assigned to the case. Martha Swenson, Jean’s housekeeper, tells them about a “Mr. Henderson”, but it’s Jean’s boyfriend Frank Niles, who has a bad habit of telling lies, who becomes the prime suspect. The detectives learn that Frank sold a gold cigarette case stolen from Lawrence Stoneman, a doctor who’s proscribed Jean sleeping pills, then purchased a one-way airline ticket to Mexico. They also discover that one of Jean’s rings was stolen from the home of a wealthy Mrs. Hylton who’s daughter was engaged to Frank….

While I did know a little bit about Brute Force prior to watching it, my knowledge of The Naked City was very limited indeed, just consisting of the fact that it was the first major American film to attempt a large amount of realism in its depiction of police work and was therefore a major influence of many films and TV programmes that followed. It’s hard to for us to imagine what a breath of fresh air it must have been, how revolutionary its approach must have seemed like. It presented a world where cases were solved by average-looking detectives doing dogged investigation which mainly involved talking to people and finding out, for example, where somebody bought an item of clothing, rather than just happening to uncover major revelations either because of their brilliance or by chance. A world where bad guys blended in and seemed disturbingly normal rather than sticking out and soon revealing themselves because of their flamboyance. A world where there’s no time or place for romance. A world where a cop’s life is neither glamorised nor shown as terrible; it just is. The plot has some twists but is still fairly straightforward when compared to many others of the time, yet that was also part of the point, it being just “one of eight million stories in the Naked City”. A great deal of on-location shooting, some of it obviously done on the sly, was also done, but the film also proved to be more genuinely experimental than I expected, with tiny detours to various other inhabitants of New York City whose thoughts we often here via voice-over, while narration by producer Mark Hellinger himself comments on the setting, the story and its characters in a way that many viewers may find intrusive but is certainly unusual, coming across as the voice of the city in a film which attempts to be, and mostly succeeds at being, a rather impressionistic portrait of New York City itself, circa 1948.

I’m not sure that we needed Hellinger telling us, over the opening aerial shots, that there was no studio work [which I don’t believe] and that many real New Yorkers feature, while shots of empty parts of the city at night including interiors of banks and the like can’t help but be a bit unsettling seeing what we’re going through right. “Sometimes I think the world is made up nothing but dirty feet” says the interior voice of a cleaner while a radio DJ wonders “does anybody else listen to this programme except my wife”? We’re then shown some a busy restaurant with a couple ordering from a menu before a deliberately jolting cut to a silhouetted killing through a window. The story of the film continues to be introduced in between more Wings Of Desire-like snapshots of the waking up, like a mother wishing that her baby was a seven or eight o clock baby rather than a six o clock one. One of the murderers clubs the other to death and a cleaner discovers Jean’s body. Detectives Muldoon and Halloran show up and work out that she was knocked out by chloroforming and then drowned in the bath. Jean’s housekeeper mentions this mysterious Mr. Henderson who was “quite tall, on the thin side” and her jewelry has disappeared. We see some of the forensic stuff, and I’d have personally liked to have seen more though I guess that it wasn’t considered to be that interesting back in 1948 and not much is uncovered with it anyway. Instead, it’s mostly investigation with Muldoon trying to get Jean’s boyfriend Frank to talk while his much younger partner and some other detectives do the leg-work following up all leads. But all this is certainly not boring, with a lot of perfectly handled and even amusing scenes such as Jean’s boyfriend Frank talking a sack of s*** about himself and having all his lies destroyed by Muldoon who likes to act as if he’s not too with it and let witnesses confront each other, while an intriguing and sordid backstory is more than hinted at regarding Jean.

The lack of big-name actors really helps in bringing an authenticity to scenes like Jean’s parents identifying the body and then talking with Muldoon on a pier; the mother’s reactions on seeing the corpse hit us powerfully as she goes from shouting that she hates our daughter to breaking down in tears and crying “why was she born ugly”? It wasn’t necessary in terms of the plot to dwell for a bit here, but the fact that it doe sepitomises much of what makes The Naked City so unique, with even the fact that the identifying is shown through a window [presumably because the room was too small for them to get a camera crew in there] working to the scene’s advantage. The performing isn’t always smooth but this seems to be, at least in part, deliberate. I’ve always felt that this kind of unvarnished, rawer kind of acting often works in films going for a documentary-like feel and mixes with the scenes where many of the people that we see aren’t professional actors at all. Only Don Taylor, who became better known as a director, as Halloran irritates with his stiffness though he does perform really well one moment when he’s in the killer’s house and is getting nervous but doesn’t want it to show. And thankfully this is made up for by Barry Fitzrgerald as Muldoon who avoids making the expected world-weariness that you’d expect this veteran cop to have be a major part of the character, and is even given some little humorous moments to play, like when he admires a lady’s hair. “Lovely long legs, keep looking at them” is his way of instructing one of his men to follow Ruth Morrison, who’s Frank’s fiancee and none to happy when she’s told that her engagement ring is stolen property. Frank is a cad, a crook and a compulsive liar but not too competent and could become a target for someone else.

The narration provides an almost god-like perspective while providing a few more chuckles, like lines like “how about those eyebrows, ever had them plucked”? as Halloran walks through a hairdressers – in fact it’s surprising how much humour screenwriters Albert Mutz and Malvin Wald incorporate. Certain narrated passages such as “James Dexter is dead and the answers must be somewhere down there” almost come across as childish and this is certainly one of those films where the narration plays a hugely important part and may grate considerably if you don’t tend to like narration in the first place. As someone who likes, for example, Terence Malick’s films, I was fine with it. It and the vignettes, which include a rather upsetting one of a small boy drowning, lessen considerably after about half way through and things do become a bit more conventional, with more use of soundtrack music where hardly any had been heard before, Frank Skinner doing the duties up to what sounded like the last three cues where Miklos Rozsa took over. A dramatic scene involving Frank and Ruth didn’t really need musical backing considering the overall aesthetic and it’s strange when we’re given two soft-focus close-ups of Dorothy Hart in said scene; they seem out of place. But we’re still surprised when things turn into all-out action for a very lengthy climactic chase set to one of Rozsa’s most exciting musical cues towards and up the Williamsburg bridge where narration comes back and seems to increase sympathy for the murderer who even gets unheeded advice from Hellinger. He becomes like so many of those old movie monsters who end up high up, cornered, defiant but sympathetic, while we marvel at the fact that there doesn’t seem to be any visible fakery, with the camera really seeming to be up there, though elsewhere a few studio sets do look like they’re being used, and hearing traffic outside while we’re inside a location is good attention to detail, but sometimes when we’re inside places we don’t hear anything at all.

The Naked City isn’t particularly interested in its characters. We see very little of Muldoon’s home life but do get to see Halloran’s wife trying to persuade him to whip their son with a belt because he walked across a park on his own. What’s unusual for the time is that the man is the one who’s opposed to doing such a thing, and he later says he admires his son. Nor do we get the expected complaining about his job; she seems to have accepted her lot, though the most memorable female character we see on screen is an old lady who thinks she’s twenty. There seems to be some social commentary on the rich being idle, narcissistic and corrupt without really laying it on. But the most intriguing thing about this film apart from its style is the tragic Laura Palmer-style backstory of its murder victim. This film being as old as it is, it has to be coy in such matters, yet we still get a picture of a thrill seeker who drove men wild. It’s not unexpected for a rascal such as Frank to cheat on his fiancee and hook up with someone like Jean and maybe they were made for each other, but then there’s also this man who delivered her things who’s been driven so mad by her being in her negligee that he says he stabbed her to death, plus another character whose life will probably be ruined by the affair that he had. But was she the user or the used? I have a Fire Walk With Me-style prequel running through my head as I type. But more than anything else one is left with the poetry that Jules Dassin brings to his portrayal of New York City, the city that never sleeps, a city full of stories, a place where a delicate balance existing between those who break the law and those who uphold it.

Rating:

High Definition Blu-ray (1080p) presentation of new 4K restoration

Again we have a preface explaining how the restoration had to be done from thirteen sources and that the original negative was lost, and again it’s hard to tell. A few shots bear a very light scratch or too, but there’s hardly any visual discrepancy between the real and studio footage; the differences in the audio stick out rather more. Blacks look terrific and depth of field seems a tad better than it was in Brute Force.

Original uncompressed mono 1.0 audio

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

Naked City Radio, a unique new audio commentary by historian and critic David Cairns featuring actors Steven McNicoll and Francesca Dymond

Arrow have opted not to use the audio commentary that was on their earlier release and also on the Criterion Region ‘A’ version. Nonetheless, I was greatly looking forward to the replacement one seeing as it’s mostly done by Cairns, though it’s a brave attempt at being different which doesn’t really come off. Steven McNicoll and Francesca Diamond are very useful when reading deleted narration and thoughts of more New York people and dialogue, none of which was necessary and in terms of the narration may have been too much. However, the interruptions by vintage material – for example, a reference to a Sam Spade radio series being immediately followed by an advertisement for one and a supposedly humorous short clip, or a reference to a particular airplane being followed by news advertising of the same plane – get irritating very quickly. Still, we learn a lot; Cairns tells us that Dassin and cinematographer William H. Daniels both made claims for originating the idea of on-location filming, how Hellinger promised Dassin final cut but either lied or the studio did the edit because Hellinger died of a heart attack just before the film hit cinemas, and how Dassin worked as an assistant director for Alfred Hitchcock on Mr And Mrs Smith and was taken too lunch by him every day but didn’t understand a thing Hitchcock said to him!

The Pulse of the City, a brand new visual essay by historian and critic Eloise Ross [16 mins]

Ross talks about the film pointing out locations and how it views New York, how it’s a film noir but doesn’t attempt to draw us in like most noir, and that some social commentary was removed from the final cut which wasn’t apparent much in the commentary. She makes the great observation that this city “needs crime to pulse”. A good overview of the film with not much overlapping with the commentary

The Hollywood Ten, a 1950 documentary short on the ten filmmakers blacklisted from Hollywood for their refusal to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee, including The Naked City’s screenwriter Albert Maltz [14 mins]

Two interviews that were on the Criterion didn’t make their way onto either this release or the previous one from Arrow, but thankfully this did. It’s a stark and chilling piece that gets through to the viewer how awful the McCarthy era was. We’re shown the “ten” in turn, told of their considerable achievements which often included films of a patriotic nature, then leaving us with the line “he is now in prison” before we move on to the next person. It’s easy for us to laugh at the description of what their supposed “crimes” were because it seems so absurd, but this was in reality a horrible period where the United States acted in a manner that would be more expected of the Soviet Union.

Jules Dassin at LCMA [52 mins]

This 2004 appearance by a very elderly Dassin at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art was not on the earlier Arrow but did appear on the Criterion. Dassin is on terrific form, often really funny as the interviewer takes him through his career. There’s a lot of emphasis on Rififi which had just been shown, and not much about these two films, though Dassin does tell of going to the premiere of The Naked City and being so upset at the editing that was done behind his back that he walked out. Highlights include Dassin’s telling of his encounter with the writer of the Rififi novel who’d had his book heavily changed by him, remembering how he’d hide out of shyness on the Alfred Hitchcock set but Hitchcock would shout out for his approval after every take, and pretending to be really embarrassed when asked about his early work. He’s a great sport and even pretends to fall asleep at one point.

New York and The Naked City, a personalised history of NYC on the big screen by critic Amy Taubin [39 mins]

I was interested at first as Taubin takes us through New York on film, saying how filmgoers never saw the real thing in cinemas until newsreels came along and movies felt they had to catch up. It’s hard for me to get to grips with the fact that my personal favourite New York film, The Clock, was shot entirely in a studio. Taubin’s account of how Pickup On South Street affected her is interesting, but my attention wavered when she went through all these underground filmmakers, and I felt that she missed some important stuff out. Woody Allen anyone?

Gallery of production stills by photojournalist Weegee

Theatrical Trailer

LIMITED EDITION CONTENTS

Illustrated booklet featuring writing on the films by Alastair Philips, Barry Salt, Sergio Angelini, Andrew Graves, Richard Brooks and Frank Krutnik

Reversible sleeves featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Sister Hyde

Two striking ’40s dramas which should have much to interest modern viewers in a fine set with plenty of additional material. Highly Recommended.

Just a quick correction: all the audio in my commentary, apart from the original script sections performed by Steven and Fran, are authentic audio from the time: all the trailers, radio and TV shows, and documentaries are real. I can understand how they might feel like annoying interruptions if you thought they were spoofs, but they’re there to give you an authentic flavour of the media world THE NAKED CITY comes out of.

Thank you for your correction…will amend review accordingly.