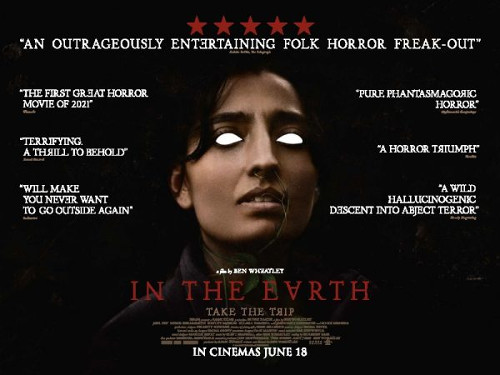

In the Earth (2021)

Directed by: Ben Wheatley

Written by: Ben Wheatley

Starring: Ellora Torchia, Hayley Squires, Joel Fry, Reece Shearsmith

US/ UK

IN CINEMAS NOW

RUNNING TIME: 107 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

It’s the aftermath of a deadly pandemic which killed Martin Lowery’s parents. Martin’s had to quarantine for four months, but is now venturing out, accompanied by ranger Alma, into a nearby forest to help his ex-colleague and ex-girlfriend Dr Olivia Wendle who’s working on a research project to use mycorrhiza [symbiotic association between fungi and plants] to aid crop efficiency . Legend has it that a monster also lives there, but it could just be a warning to kids not to go in there. On their first night in the forest, Martin and Alma are attacked and their equipment trashed and shoes stolen. They then encounter the seemingly friendly Zach, but is he really as he seems or something far worse….

For some of us, a new film by Ben Wheatley is an event, something to be greeted with excitement and the almost certain knowledge that the end result won’t be a disappointment. Well – until last year’s Rebecca. Seeing as we had reviews of all of his previous films except for his debut feature Down Terrace, I was intending to do Rebecca too, but never got around to it. Mind you, I may well have just repeated “why has Wheatley made this”? a huge number of times and posted it as my write up. It wasn’t so much that Wheatley was out of his depth as one wondering what on earth he saw in the material – and that’s not to knock Daphne du Maurier’s novel nor Alfred Hitchcock’s film adaptation, both of which are stone cold classics. But Wheatley had also made another film, the title of which alone conjured something much more – well – Wheatley-ish. One has to admire anyone who goes out and shoots a film in the middle of a pandemic, but the fact that In The Earth was written in ten days, then shot over just fifteen days with a very small crew, immediately brought back memories of his wonderful micro-budget historical drama/drug hallucination/folk horror A Field In England to which this film seems to be some kind of spiritual sequel. This would be the real Wheatley, delving again into his particular interests while still coming up with something fresh and original. Indeed, In The Earth is pure Wheatley through and through. However, whether it’s particularly good is a harder question to answer. The man is obviously playing with his beloved folk horror elements again, and presents us with a slow burning but intriguing first two thirds, but then virtually things away with a final act that refuses to answer any of the questions that have been thrown up – though maybe that’s the point.

There’s been some promotion around In The Earth saying that it’s about the current pandemic which is still ravaging the globe though seems to be finally showing signs of slowing down, though that’s not entirely true. There’s a brief mention of it during the opening scenes which also feature some very familiar-looking masks, plus a couple of scenes where people are sprayed down with disinfectant, but that’s it, and it’s not even made clear if the film’s pandemic is this pandemic or a fictitious one. Aside from the likes of Corona Zombies or even Birdsong which are basically exploitation, this does raise an interesting question. Should films acknowledge Covid or just pretend it doesn’t exist and continue to take place in the world we were living in before this hell started? Personally I’d much prefer they totally ignored it; seeing as it’s affected far too much of our lives already, it would be nice to go to the cinema and be secure in the knowledge that we won’t be reminded of it. But Wheatley nicely uses it as a starting point for his film then ignores it which I guess is a good way to go about things, though to be honest I’m not sure he needed to mention it at all seeing as it doesn’t affect the proceedings at all; I fully expected it to come back with a vengeance in the climax, but it fails to do so and by then we’re in a very different world. Anyway, we first meet Martin at the end of his four-month quarantine period in a place which doesn’t seem to be his actual house, passing a physical examination so he can go and help Olivia with whom he used to both work and play. She’s working in a government-controlled outpost located in a fertile forested area [we’re just outside of Bristol] to help crop efficiency with mycorrhiza.

After meeting his guide Alma, he learns of the local legend of Parnag Fegg, a woodland spirit, a picture of whom adorns one of his lounge walls. He supposedly lurks in the forest and kills intruders, but maybe there’s no truth in it, maybe the being was invented to stop children from wandering off into the forest? The following morning, Martin and Alma begin their two-day hike toward Olivia’s site. Ellora Torchia and especially Joel Fry, who has a great ,unassuming ‘everyone’ quality about him, are fine in their roles, but Wheatley’s writing fails them. Their characters are flat and dull with no interesting attributes at all, while virtually all Wheatley has them say to each other is what the plot is; what they are doing and why is this happening and so forth. We don’t always need witty banter, but something better then what we got would have been nice. The two don’t really have any actual conversations. However, I did like the scene where Martin doesn’t have a clue on how to put up a tent; it’s something we rarely see in movies, even if it’s of course possible to groan at yet another modern film where the woman is more intelligent and capable than the man in seemingly every way; this ain’t equality folks! Anyway, Alma informs Martin that Olivia hasn’t been heard from in months, and then finds a small box where Olivia would leave notes and updates of her research, only to discover it empty. The next day, they reach each Olivia’s “mycorrhizal mat,” a wide-spanning area where the forest’s flora is connected in a singular network using fungal filaments, and pass by a wrecked campsite. At night, Martin discovers an odd, ring-shaped rash on his arm before he and Alma are assaulted by unknown assailants who also raid their camp, destroy their equipment, and loot some of their supplies. Forced to carry on barefoot, Martin unsurprisingly badly cuts his foot on a sharp stone.

The two other characters of this essentially four-person film [two appear at the beginning but are never seen again] are Zach and Olivia. Zach disinfects and stitches Martin’s wound and gives them both much-needed shoes, food and a drink made up of various flower petals. However, the latter sedates them, and Zach then takes their unconscious bodies, dresses them in white robes and takes several ritualistic photographs of them in various poses with white paper ellipses placed over their eyes. Martin also discovers that his arm has been carved and stitched with a strange symbol. It’s revealed that Zach believes that Parnag Fegg is very real, worships him, and periodically makes sacrifices to him. He also believes that Parnag’s presence is in this large stone. He’s brilliantly played by Wheatley regular Reece Sheersmith with just the right level of humour to make him somewhat endearing while ensuring that we’re still frightened of him. And then there’s Olivia, who was engaged in these mycorrhiza experiments but has now created this electronic soundboard full of lights and noises which which to hopefully communicate with the entity inside the stone. So what we have here is the old struggle between religion and science, between worshiping and studying, with the science and studying here hardly seeming like the rational side of things. And maybe neither are adequate to deal with Wheatley’s favourite interest; the fact that modern civilisation was built upon the irrational ancient world of our ancestors who were far more tuned into our planet and in particular nature than we are now. Maybe it’s best to just lose oneself in the wonder of nature and not try to make sense out of it all [maybe this is more about the pandemic than I initially realised]?

That’s fine, but Wheatley seems to lose the plot towards the end, and not just because characters keep being knocked out and then waking up what seems like a few minutes later, while others show up in specific places and at specific times just because the story requires it. There’s of course an argument for the idea that a quest to figure out the impossible only really gets better if it gets more and more confusing, but Wheatley, despite slightly riffing at times on other sources such as Stalker and The Stone Tapes, increasingly comes up with situations that decease in interest, and seems to rely on having many of them taking place in flickering strobe lights and strange sounds to have an impact – though what this does more than anything is just make it hard to see what’s happening, especially when Wheatley goes unpleasantly ‘shakycam’ on us. Camerawork is all over the place in style, though the forest is lushly photographed and cinematographer Nick Gillespie sometimes does some good stuff with his handheld work such as when Zach is firing arrows at a fleeing Alma; here, the whirling camerawork creates a real sense of panic while we still have clarity of what’s going on. There are plenty of grisly moments, some of which we’re clearly intended to chuckle at, such as Martin stumbling [though he still walks amazingly well all things considered] and accidentally putting his hand on somebody’s guts. I tend to find it rather lazy when filmmakers go for the “let’s not take this violence too seriously” approach unless the film in question is an out and out comedy, though I guess that when we’ve pretty much seen it all it’s getting harder for us to take things like yet another eyeball skewering too seriously.

Martin’s frequent pain is made into a darkly amusing running gag where nasty things keep happening to him, often for his own good. At one point his infection spreads to his toes, which is an excuse for what would be the most intense and grimmest scene of horror in a Wheatley film since that bit with the hammer in Kill List if it wasn’t for the humorous aspect lent by the matter of fact attitude of Zach – though some might say that makes it actually nastier! And then at the end things eventually go full-on psychedelic with some nifty trippy visuals; manipulated nature images and multiply printed shots probably weren’t hard for Wheatley to put together at home but impress nonetheless. However, this takes away from the themes that he seems to be looking at, such as the impact of isolation and an unknowable future [for a second time, maybe this is more about the pandemic than I initially realised], even though this is no doubt another work from him where fans are working out where it fits into this strange kind of cinematic universe most of his output seems to take place in. A very John Carpenter-esque synth score from Clint Mansell is a real highlight; indeed In The Earth has several highlights, and that Wheatley melding of realism,wryness and oddness is well to the fore, again showing up what a unique filmmaker he is, but this offering seriously falls down with the screenplay concocted which fails to do justice to the ideas it throws up.

Be the first to comment