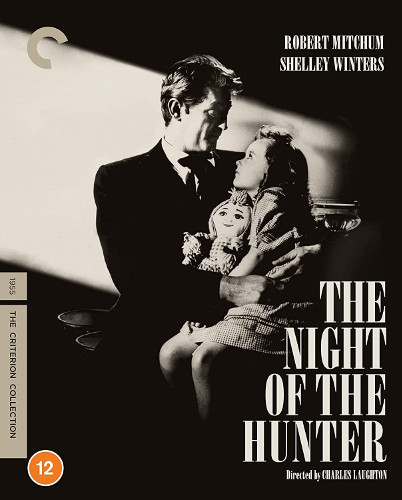

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Directed by: Charles Laughton

Written by: Davis Grubb, James Agee

Starring: Billy Chapin, Lillian Gish, Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: 28TH JUNE, from THE CRITERION COLLECTION

RUNNING TIME: 92 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

SPOILERS!

During the Great Depression, Ben Harper kills two people in the process of robbing a bank of $10,000 to provide for his children. Before he’s arrested, he convinces his young children John and Pearl to hide the money and not to tell anyone, including their mother Willa. Ben is sentenced to death, but not before he tells a cellmate by the name of Harry Powell about the money. Harry is supposedly a man of the cloth, but he’s actually a psychopathic swindler and murderer of widows. Harry decides that Willa will be his next mark, figuring that someone in the family knows where the money is hidden. Willa, who feels she needs to atone for her sins which led to Ben doing what he did, is easy prey for Harry’s outward evangelicalism, and Pearl likes him too, but John doesn’t trust him at all. Harry quickly figures out that John and Pearl know where the money is….

There are a fair few filmmakers who only directed one film. Three that immediately come to mind are Leonard Kastle [The Honeymoon Killers], Dalton Trumbo [Johnny Got His Gun] and Saul Pass [Phase IV]. Their movies were good enough to make us wish that they’d made more, but two other names are the real tragedies. Second is Herk Harvey, whose 1961 Carnival Of Souls is a creepy classic of micro-budget ingenuity. But he’s beaten by Charles Laughton with The Night Of The Hunter. Laughton was a prominent character actor in Hollywood for several decades. He first came to my attention with the 1939 version of The Hunchback Of Notre Dame where his incredibly sensitive acting shone through exceedingly grotesque makeup; The Private Life Of Henry VIII, Spartacus, Rembrandt and Witness For The Prosecution are other notable credits. And then he directed one film, a film I would automatically call a masterwork except that, hurt by its poor reception, he never made anything else again. The blend of film noir, horror, fairy tale and religious parable shows a unique cinematic voice that we could have done with hearing from a few more times. At its heart it’s a tribute to the resilience of children in addition to being a warning to look out for wolves in sheep’s clothing. It features one of the all-time great villains in movie history in the form of Robert Mitchum’s truly evil, yet charming when he needs to be, reverend; this guy haunts you for ages. You’ll realise where the oft-used idea of someone having LOVE tattooed on one hand and HATE on the other came from.

Literary agent Harold Matson sent a copy of the 1953 novel by Davis Grubb to producer Paul Gregory, who sent it to Laughton. He loved it and discussed a film version with Grubb who even drew sketches, many of which were used as storyboards. However, United Artists wanted James Agee to write the screenplay, a screenplay which for several decades was thought to be so messy that Laughton totally rewrote it, though the eventual finding of Agee’s draft revealed that Laughton just heavily condensed it as it was very long. After some fuss the script was approved, but Christian groups continued to object to the film’s production. Gary Cooper turned the role of Powell down as he thought it would be detrimental to his career, while Laurence Olivier was interested but not free for two years. Mitchum was eager to play Harry, and according to him impressed Laughton when the latter described the character as “a diabolical shit,” and Mitchum answered “Present!” Laughton’s wife Elsa Lanchester turned down the role of Rachel, suggesting silent movie star Lillian Gish. Filming took place at Pathé, Republic Studios, and the Rowland V. Lee ranch in the San Fernando Valley. Rather than shooting with traditional takes, Laughton had the crew only slate at the beginning of each reel of film and let the camera roll continuously until the reel ran out. It’s said that Mitchum directed a few of the children’s scenes, though there’s no evidence of him doing this on the Charles Laughton Directs The Night Of The Hunter documentary. He was, though, drinking heavily and, when told one morning by Gregory that he was too drunk to work, he went over to Gregory’s Cadillac and peed on the front seat. Despite objections from the Legion of Decency and other church organisations which would normally draw interest, the poorly promoted The Night of the Hunter was not a success with either audiences of critics.

The beginning was originally going to be the ending; the disembodied faces of some children and an old lady against a night sky referencing the Bible and telling us to “beware of false prophets” commence things in an appropriately strange manner before several aerial shots take us to an bucolic scene of children playing and singing a song that turns to horror very quickly as they find a dead body. We’re left in no doubt as to the identity of the perpetrator of this foul dead; ‘Reverend’ Harry Powell, seen driving along in a car, talking to God. He’s not sure whether he’s killed six or twelve women, but he vents his hatred. “Not that you mind the killings, your book is full of killings. But there are things you do hate, lord. Perfume-smelling things, lacy things, things with curly hair”. While few Christians would see him as a properly religious man, there’s little doubt that the insane Harry thinks he is, even though money and a hatred of sexuality seem to be the main things that really drive him. And maybe he’s sometimes thinking of Alfred Hitchcock’s Merry Widow murderer from Shadow Of A Doubt which may have been an influence. We next see him watching a stripper, and when he puts his HATE hand into his coat pocket the blade of his knife flicks open and tears through, a startlingly obvious phallic symbol, while we get the first of the film’s many artful yet simple visual devices; Harry is illuminated, the people sitting in the row immediately behind him have half their faces illuminated, and everyone behind is in silhouette. He’s then arrested because his vehicle is stolen, but lucky for him he shares a cell with Ben. Thinking Harry’s a real priest, Ben tells him what he did and why he did it, though doesn’t reveal where the money he stole is. Ben is executed, and we linger on the hangman, even finishing with a lengthy shot of his face; the character does briefly reappear, but it still seems odd. But then this is an odd film where loads of strange details generally add to the overall effect.

Harry arrives at the town where the surviving Harpers live on a menacing black train, his presence first revealed to John and Pearl when the huge shadow of his hatted head looms on their bedroom wall, initiating a fantastic building up of suspense and terror which Hitchcock would have struggled to match. Many take to Harry, especially Willa’s employer Walter Spoon’s wife Icey who thinks it best that Willa remarry quickly. The initially suspicious Willa agrees, but the wedding night proves to be not what she expected. How on earth did him tormenting Willa with shame for her “filthy” sexuality get by the 1955 censors? The poor deluded woman, thinking that she should do penance for her sins, easily comes under his control, and while we only see her hit her once, this is clearly an abusive marriage. John accidentally reveals that he knows the money’s location, but when Willa overhears Harry threatening Pearl, she barely notices. In a truly extraordinary scene which is staged like a twisted ceremony with Willa seeming to know what’s about to happen and even welcoming it, Harry kills Wilma, leaving the two kids alone in the house with Harry, and these scenes have a really grim edge to them; rarely were children in such frightening and believable peril at the time. Harry calling “chill…..dren” as he looks into a cellar is probably the stuff of nightmares for children of a similar age to John and Pearl and still unnerves us adults. When they take flight, John is never far behind them even though he never seems to hurry. We get some reprieve from the terror when the kids arrive at the house of Rachel Cooper who looks after stray children, but we know that John will soon find them. Perhaps the actual climax isn’t quite the seat-grabber one may expect, but the dwelling on sentiment and positivity in the final scenes probably works for most because Laughton clearly seems to believe in such things, this is no studio-imposed softening.

The visual style, often inspired by German Expressionism with its bizarre shadows, distorted perspectives, surrealistic sets and odd camera angles, is cleverly worked out; this was most definitely not a case of Laughton and company just throwing in everything they could. The production design, taking advantage of the smallish budget, seems dictated by the idea that children only notice part of their surroundings, so places are missing bits or only exist in two dimensions. The town initially seems to be right out of a Norman Rockwell painting; we’re asked to feel nostalgic for a simple, idyllic Americana. However, as Harry’s influence increases, darkness replaces the sunniness, such as a picnic by a river; it should be bright, emphasising the beauty of the surroundings, but instead cinematographer Stanley Cortez uses as much darkness as he can while still giving the impression that it’s during the day. The Harper house looks far too small to live in from the outside and only seems to be a few feet deep even when we’re inside. Willa’s bedroom is topped by a steeple formed by beams of light and looks like a cross between a chapel and a crypt; a simple but genius device by production designer Hilyard Brown which is a perfect setting for what is essentially a bizarre sacrifice. When the children are on a boat going down a river, cutout hills, twinkling stars and foregrounded shots of animals from frogs to rabbits combine to create something that has an astonishingly dreamlike effect as strong as the best of David Lynch. The significance of the animals is something I’m not sure about. I like to think that they’re protecting the fugitives in their journey from total terror to sanctuary, but who knows what was always going on in Laughton’s mind? There’s even a shot where Mitchum is bathed in light and Gish in dark; a curious switch, though it reminds us of how Gish’s character seemed harsh when we first met her, even smacking John’s bottom when he’s already been through so much, while we’re possibly invited to see how Mitchum can attract people. Things aren’t always as clean cut as they seem.

Laughton proved himself to be a highly inspired filmmaker. Probably the most iconic shot is when the silhouette of Harry is seen atop his horse on the horizon riding into the frame in the distance by John, but my favourite is when the children are sitting outside the front of the house with the money and Harry appears in the doorway and very slowly advances towards them from behind. Even back then, most filmmakers would try to enhance the excitement with cutting, but Laughton just lets it play out in one shot, making Harry even more menacing. Mitchum stepped outside his usual movie persona [as he did, though not to as great a degree, in Cape Fear where his character has certain similarities with this one]. He’s extremely frightening as the ultimate snake oil salesman and even gets away with some comedic bits like some bizarre yelling sounds he makes on several occasions. His tripping over something during one major sequence is something we buy because otherwise there’s no way those two kids would have got away from him. I’ve always loved Mitchum; his extremely laid-back manner, added to the fact that he rarely seemed to think much of his profession or indeed his acting [though he did mention The Night Of The Hunter as his favourite of his films], concealed, for me, a very intelligent performer who knew his craft impeccably. Gish is the perfect opponent for Mitchum; we believe in her goodness. The character is strong, yet is hardly angelic; she has a little element of coldness which we partly though not entirely come to understand. She’d be a great foil for Dracula.

Billy Chapin and Sally Jane Bruce as the children don’t always seem to hit their marks, but then they’re tough parts. James Gleason has some scenes as a heavy drinking riverboat captain who deviously seems to be set up as a major character who will take part in the fight against evil and greatly aid the kids. His final scene leads to the most haunting underwater corpse shot you’ll ever see, a shot imitated very often. So much in this film influenced later works, yet there’s still no film quite like it. It doesn’t even feel particularly dated except for maybe the insistent music score by Walter Schumann, though that’s also been carefully constructed to form part of the whole experience, its several distinct themes often being melded together as the elements of the story clash. There’s even an ironically romantic waltz accompanying the ill-fated marriage as well as a later scene involving the oldest of Rachel’s charges who’s attracted to Harry. An original song named ‘Pretty Fly’ is used several times but most effectively during the river voyage when Pearl sings it. I remember when I first saw this film this moment affected me immensely; it seems to emphasis the children’s innocence but I couldn’t work out at the time if it was their strength or hopelessness. Harry sings a hymn called ‘Leaning On The Everlasting Arms’, usually when he’s outside houses, much like seen Poltergeist 2‘s frightening religious bogeyman Reverend Henry Kane would do.

Of course by 1985 it was obviously okay to present Christian folk in a bad light, but in 1955 it was incredibly bold to present religion as an influence for unthinking conformism and hypocrisy, and this is not just regarding Harry; the sanctimonious Icey and her self-righteous ilk are easily converted into a lynch mob. But I don’t think that Laughton and Agee are attacking religion per se; they’re just showing how it can be corrupt and perverted. Alice’s Bible teaching is largely positive because she teaches by example, and stresses values like understanding and forgiveness which are important even if you’re not a person of God. The Night Of The Hunter reminds us that, even though unspeakable evil exists, evil which is exceedingly devious, there’s enough good to thwart it, but we should always be on our guard. And it does it in one of the most cinematically creative films of the 1950’s. It’s an amazing piece of work. It was ahead of its time in 1955, yet in some ways still seems ahead of its time in 2021.

SPECIAL FEATURES

New digital transfer restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive

As it says “new“, I’m assuming that this is not the same restoration that was on the 2010 North American Criterion release of the film, nor is it the one that was on Arrow’s 2013 UK Blu-ray. Not owning either, I can’t say for sure. In any case, this is a fine restoration of a film that’s probably problematic due to the number of composite shots. A few instances of grain cluster and mild flickering do come along, but nothing too distracting. The detailed picture shows up the artificiality of the sets far more than the DVD, but is that really a problem in this film? The many blacks sport no visible crush meaning that we can truly enjoy those incredible compositions.

Audio commentary by second-unit director Terry Sanders, film critic F. X. Feeney, archivist Robert Gitt and author Preston Neal Jones

Criterion have ported over all the special features that were on their Stateside release, meaning that UK fans who already own the Arrow Blu-ray should be tempted to buy this one too, the Arrow only having the Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter documentary and Cortez interview. This commentary is an absolute treat as our three experts plus the second-unit director discuss everything concerned with the film, including even some possible flaws; there’s a difference of opinion on some of the humour. There’s a great story on how Mitchum saw the rushes and vomited, but not because he was angry; it was because, as he said, “I had no idea I could be that good”. Sanders points out the bits he shot, and we are told a lot of things that I certainly hadn’t noticed before, like the way many shots are replicated with often different actors later on. Great stuff!

“The Making of Night of the Hunter” documentary [37 mins]

Gregory, Sanders, Jones,Feeney and another film expert Jeffrey Couchman repeat a lot of stuff from the audio commentary here, but it’s interesting to see some of the sketches by Grubb, Sanders and Laughton. We also learn that Agee actually wanted a mosaic of loads of kids of different ethnic backgrounds at the end, and that Cortez shot the film with a new format called the Tri Ex process which deepened the contrast between light and shadow.

Interview with Laughton biographer Simon Callow [10 mins]

The always erudite Callow remarks that these days Laughton is far better known as the director of The Night Of The Hunter than for his acting, how his fear of coming out as a gay man and his sexual journey may have been important in the film’s view of religion and sex, and how he doesn’t see it as a frightening film at all.

“Moving Pictures” BBC TV show excerpt [14 mins]

Obviously not all of the programme, this 1995 effort has Mitchum, Winters, Gish via a 1978 interview, Cortez, Sanders, editor Robert Colden and production designer Hilyard Brown celebrate the film’s 40th anniversary. It’s all very warm and fuzzy, and mostly stuff we’ve heard before too, but it’s nice to hear how Laughton got so insecure from others giving him their ideas tghat they stopped doing so.

“The Ed Sullivan Show” TV show excerpt [3 mins]

It doesn’t say whether the deleted scene performed here by Winters and Peter Graves in 1955 was filmed or not, but it’s very good. Willa is visiting Ben in prison, and he wants her to marry someone else “good, kind and steady” but she tries to get him to tell her where the money is.

Interview with cinematographer Stanley Cortez (12 mins]

Presumably part of a French series on great cinematographers, this has Cortez, between being every so slightly grumpy at the journalist’s questions or not being allowed to finish, tell of how he used four rather then the usual ten lights in a scene, how it was his idea to have the waltz musically dominating one section and Laughton told Schumann to write one, and how a good cinematographer changes his preconceived notions when he arrives on set and sees the performers and the environment.

“David Grubb Sketches” picture gallery

Theatrical Trailer [1 min]

DISC TWO

“Introduction” featurette [17 mins]

Leonard Maltin interviews Gitt about the feature to follow. There were a huge number of outtakes and rushes in Lancaster’s possession because of the cameras running uninterrupted through each reel. Gitt spent many years matching sound with picture, then cutting the material down to a manageable length. He also tells us that the occasional dissolves sometimes with music indicate where finished footage has been put in because the corresponding material was missing, and how the train shot was footage from another film which Cortez remembered and hunted down.

“Charles Laughton Directs The Night Of The Hunter” documentary [159 mins]

It’s possible that you may want to watch this in two parts due to its length, and some of the information at the beginning will be very familiar, but this is mostly fascinating stuff, almost playing as an alternate version of the film due to the scenes being placed in the order they appeared in the finished product, rather than the order in which they were shot. It begins with the originally intended introduction to the film which had Laughton speak the lines that were eventually given to Gish, then proceeds with most of the film’s scenes being tried out, often many times and seen from different angles. Laughton is indeed very patient with the children, though one senses an impatience with Winters especially during one small portion where the visuals are missing. The many treats include lines that were later cut out, Emmet Liden’s scenes before he was replaced by Gleason, Bruce singing which was dubbed over by someone else, and Mitchum replying to “keep talking preacher” with “I would if I could remember the next line”.

A one of a kind all-time classic in an excellent package. Very Highly Recommended.

Be the first to comment