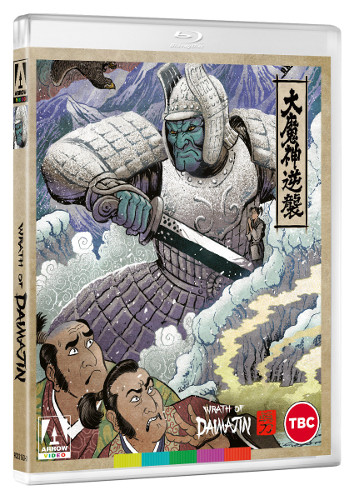

Daimajin, Return of Daimajin, Wrath of Daimajin (1966)

Directed by: Kazuo Mori, Kenji Misumi, Kimiyoshi Yasuda

Written by: Tetsurô Yoshida

Starring: Hideki Ninomiya, Kôjirô Hongô, Miwa Takada, Shiho Fujimura, Shinji Hori, Yoshihiko Aoyama

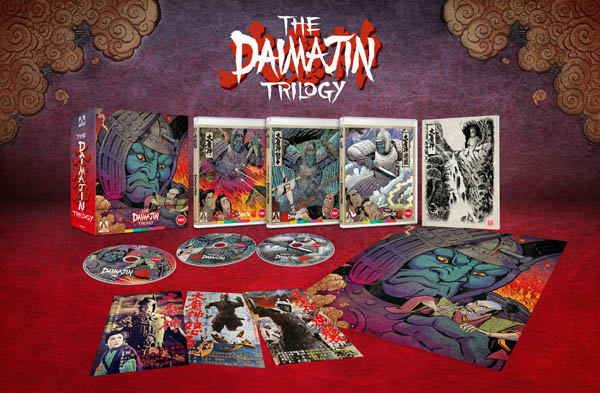

THE DAIMAJIN TRILOGY: On Blu-ray 26th July, from ARROW VIDEO

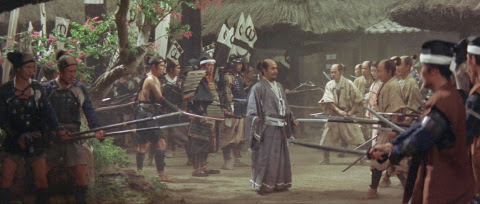

The Daimajin trilogy occupies an interesting place in the Japanese kaiju eiga [monster movie] genre. While they do indeed have a monster, a walking statue, for much of their length they’re medieval period pieces, and even more unusually were all shot simultaneously and released in 1966 with three different directors and predominantly the same crew, and all essentially tell the same basic story. contained similar plot structures involving villages being overthrown by warlords, leading to the villagers attempting to reach out to Daimajin, the great demon god, to save them. I hadn’t seen them in many a year, so of course I was most keen to check them out again courtesy of Arrow Video who have released all three films in their latest great-looking box set.

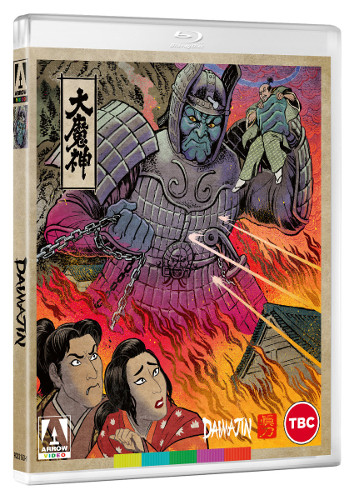

DISC ONE – DAIMAJIN [1966] AKA MAJIN THE MONSTER OF TERROR

RUNNING TIME: 84 mins

In medieval Japan, a large stone idol of a mountain god stands half-buried atop a waterfall. Supposedly this god trapped an evil spirit called the Majin inside the statue and the nearby villagers worship him at a shrine, hoping that the god will continue to keep the Majin imprisoned. Earth tremors are interpreted as him attempting to escape. Lord Tadakiyo Hanabasa is killed by his power-hungry chamberlain, Odate Samanosuke, but his son Tadafumi and daughter Kozasa, assisted by the samurai Kogenta, escape and are taken into what is supposedly forbidden territory by priestess Shinobu. As they grow up under the watchful eye of the Majin, Samanosuke enslaves the village and forbids gatherings and prayers at the shrine….

I suppose the first thing I should say is that, as I type, I’m a bit confused as to the title character. I think that the statue stuck in the side of a mountain is of the god that imprisoned Daimajin aka the Majin, but I’m not sure. And, if the Majin, who’s an evil spirit, is indeed trapped in there, why is it that, when the statue comes to life, we see a meteor-like object flying around. This object is possibly supposed to be the Majin, but surely if it is then why is the statue alive without him being inside it? I’d imagine that the Majin is supposed to be responsible for the statue coming to life, seeing as the statue doesn’t seem to differentiate between good and evil people until in the final scene, which leads one to think that the statue is more evil than good and therefore possessed by an evil spirit, not by the actual mountain god at all [though less a god in the way that we know] who imprisoned him in the Majin in the first place. And isn’t the Majin supposed to be the name of the statue too? Of course I could just be having a slow day but some clarification would have been good, though of course it’s possible that if I was Japanese I would understand things much better. Any way, the first film in the trilogy is still cracking stuff for much of the time. I hadn’t seen any of these films for a very long time indeed and I did wonder if they might come across a little more than lots of build-up to some very late in the day monster action. Around half way through, this one does begin to tease and tease us about the forthcoming awakening of the main attraction, but we’re involved all the way up to the big event because we’ve had a well balanced and well handled melding of action, drama and folklore that benefits greatly from a considerably larger budget than Daiei gave to the Gamera films of the time, and very assured direction by Kimiyoshi Yasuda.

The kaiju lover who’s not too familiar with these films may very well giggle with delight at the opening titles, not because of the fire imagery but because of the hugely distinctive music of Akira Ifukube who was to the Godzilla series to John Barry was to the James Bond series; in both cases the composer created a specific musical style and identity for each franchise which has stuck despite all the other composers who’ve created music for them since. Perhaps because he also wrote a lot of concert music, Ifukube often recycled themes and motifs for his film work, and his main title piece here, while full of ominous menace, employs the familiar da-da-da phrase that’s part of one of Godzilla’s themes. A close-up of an eye receding into the mountain also creates a strong mood while we then slowly pan across a lovely set of fog, rock and dead trees; it’s not remotely realistic looking, but shows that it wasn’t just the likes of Roger Corman, Mario Bava and the folk at Hammer who were interested in and good at creating this kind of aesthetic. We are shown a family inside their home before an earth tremor. “The Majin is stirring, trying to get out” says the mother. That night, a procession goes to the shrine to pray to the mountain god to keep the Majin at bay, shown in a shot which is both evocative and economic as we see a procession of torches in the distance before the camera pulls back to reveal Lord Hanabasa watching. He’s not around for long because, while the villagers are attending this ritual, Samanosuke leads a takeover and Hanabasa is killed. Blood is almost avoided, but the yells and cries of the combatants provides some realism. Little Tadafumi wants to go to his father but is thankfully prevented from meeting the same fate and is whisked away by Kogenta, who take her to the priestess Shinobu into a holy cave near the statue where they can grow up in safety.

Ten years later and the villagers have to slave away building things for Samanosuke who doesn’t even let them have most of their crops due to very heavy taxes. A worker with a very sick wife tries to help a man who’s been beaten but tells his son Take-bo to get away, partly mirroring the earlier situation with Hanabasa and Tadafumi. It’s a place that’s ripe for revolution, and surviving Hanabusa retainers are starting to return. While hardly thrill-packed, the story moves at a fairly quick pace so that one doesn’t dwell on the silliness of not one but three major characters who are obviously going to get captured or worse when they venture into the castle . There’s much pleading and threats like “change your mind or you’re suffer the consequences” but of course Samanosuke doesn’t listen and just wants to punish and kill. Take-bo becomes as much of a hero as Tadafumi, taking matters into his own hands and braving a forest which is reputed to be haunted. The scene where he imagines ghosts are around him has nothing to do with the story yet, despite the extremely primitive rendering of the spooks with sheets, a toy skeleton arm and rapis zooms into animal eyes, it has a strong atmosphere and is a really vivid illustration of a child’s imagination taking over. The Majin, as I’ve said before, takes ages to sort things out [though Mothra rarely seemed to be in a hurry to hatch or wake up either], and it takes actual desecration for him to come to life, in a positively seamless composition of him emerging from the mountain on the right hand side of the screen while two people watch in awe on the left. Clouds form and then part of the sky becomes red and the Majin is free to wreck and kill, his face now green.

One can’t help but feel sorry for poor these medieval folk having to make do with things like catapults, chains and fire to fight off a monster, no jet fighters or ‘maser’ cannons here. Thank goodness he’s only around thirty feet tall that’s what I say, otherwise everyone would have been wiped out in a couple of minutes. The blue screen work putting Majin in the same shot as humans is way above average for the period in any country; even on High Definition which tends to highlight seams in the special effects, blue lines are rare or greatly minimised, while the matting is nearly flawless. In some shots they’re clearly using a nearly-full sized prop, something obviously easy to do when your monster isn’t Godzilla-sized but still unusual. Shooting the Majin chiefly from low angles enhances the feeling of menace and the permanent scowl he has once he’s alive is very cool; yes, we can tell that a human being is making the scowl under lots of makeup, but it’s still pretty effective in a certain way – after all, realism is rarely what Japanese monster movie makers were after in the first place. Showing the eyes of Chikara Hashimoto the actor inside the suit but also in a few shots the skin around them was a mistake though; the suit can’t help but look like it’s made of rubber, and a scene with a giant hand is a low point even though filmed from behind so that – but then giant hands rarely looked good. Still, goofy antics of the kind that other kaiju were getting up to at the time are avoided; the Majin just walks slowly as we hear every foot step and single mindedly smashes, crushes and stamps. His end, which perhaps deliberately recalls 1920’s The Golem, is well staged too and the effect is very good. The person responsible for all was cinematographer Fujio Morita who was given special effects duties.

But in no way is the monster stuff all this film has to offer. The most memorable scene just involving humans has one character very slowly sway and fall down dead against an almost entirely black background with only a candle appearing on the far left handside as her killers watch; it’s hugely theatrical, but no Gamera or Godzilla film had a scene like this. Yasuda also does well with an extremely suspenseful and quite drawn out rescue attempt, aided greatly by Morita’s cinematography of making fine use of shadows; it almost feels like we’re watching a ’40s film noir. Tetsuro Yoshida’s screenplay gives us some violent sequences which Yasuda stages with relish even if the action isn’t shown in detail. Samanosuke tortures somebody with re-hot iron pokers while the Majin smashes a huge nail into somebody’s stomach, thereby impaling him on a wall. Performances are a bit more naturalistic than what you normally get in Japanese period pieces of the period; even Ryutaro Gomi as Samanosuke isn’t quite the over the top villain you may expect though he’s still very menacing and boo-worthy. Ifukube’s mostly moody score is often allowed to play out in long segments, often evoking the environment such as a lengthy journey to the cave. Two pieces later turned up, slightly different, in Godzilla Vs King Ghidorah. Well, as I said earlier, he did like to recycle, but his unique style is perfectly suited to this tale. Overall Daimajin might surprise newcomers with the care devoted to its production and its serious handling.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

Brand new audio commentary by Japanese film expert Stuart Galbraith IV

The special features kick off with a commentary from a veteran writer and talker about Japanese cinema, who adds in material from a telephone conversation he’d had with star Yoshihiko Oayama who plays Tadafumi. Oayama’s recollections of working on the film are interesting, but Galbraith unfortunately doesn’t talk much about it and hardly ever refers to what’s happening onscreen, preferring to discuss the background to the film’s production and spending a lot of time on my commentary bugbear – lengthy biographies, though I was interested to learn about the anibawa which are Japanese golems, while we do hear that the plentiful sand or dust was actually powdered sweet potato which often got in people’s eyes, a cable broke in the scene where Majin tosses a cross aside, and two origin stories of how the project came about exist; the head of Daiei Akinawa Suzuki claimed that he saw a photograph of a clay statue and the next day brought it to the studio saying “couldn’t we make a movie out of this” though most sources say that producer Hiyoshi Okada was the one who first mentioned the project, pitching it as a version of the 1935 version of The Golem. Galbraith IV is always very clear and easy to listen to, but the low amount of commenting on the actual film means that it’s one of his lesser efforts.

Newly filmed introduction by critic Kim Newman [15 mins]

The always welcome Newman makes his usual good observations, from the villains being usurper, invader then exploiter, the similarities to the Zatoichi films, and the good guys having to be ineffectual

Bringing the Avenging God to Life, a brand new exclusive video essay about the special effects of the Daimajin films by Japanese film historian Ed Godziszewski [17 mins]

Another familiar expert talks over a series of great photographs about the special effects, many of which were composites of raw footage rather than matting, which explains why they look so good. We learn that the cleft in the Majin’s chin was intended to recall Kirk Douglas, how Morita wasn’t worried about Hashimoto, who could hardly see what with all the dust about, being injured by walking near explosives because he was wearing a suit and would therefore be protected, and of rows between the different departments which all thought that the Majin suit should be in their care. We even have a clip from the film where you can see debris hitting Hashimoto on the head. Fascinating overall.

Alternate opening credits for the US release as Majin The Monster of Terror

Trailers for the original Japanese and US releases

Image gallery

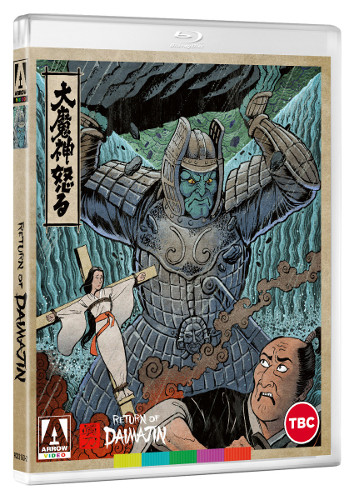

DISC TWO – RETURN OF DAIMAJIN [1966[

RUNNING TIME: 79 mins

Slaves of Mikoshiba flee their mountainous homeland which is ruled with an iron hand by the warlord Danjo Mikoshiba. Nearby are the Nagoshi and Chigusa villages, both situated on lakeshore land and coexisting in harmony. Both Nagoshi and Chigusa are happy to take on the refugees. When the Nagoshi residents pray to the Majin statue which is on a small island in the lake, they witness a prophecy come to life; the statue’s stony face turns red, portending the destruction of their homeland, though the real danger seems to be from the rulers of Mikoshiba who are plotting an attack on Chigusa and Nagoshi, scheduled to take place during a peaceful ceremony….

Well any confusion as the nature of the Majin is removed for this first sequel;. there’s no distinction to their being two mystical entities, one being the god statue, and the other the evil spirit confined within it. Here, it’s strictly the god alone who is prayed into existence. In fact not even the word Majin is used, but of course I’m going to call him the Majin anyway, or in fact just plain old Majin as it’s quicker. So Return Of Daimajin is sort of more of the same, returning screenwriter Tetsura Yoshida obviously asked to follow the template, but there are enough differences to distinguish it. Instead of beside and up a mountain, the film mostly takes place beside a lake, an island in the lake, and the lake itself, which means that Majin has also moved. There’s much more action, with plenty of swordplay, and the story is taken at a much faster pace; Daimajin did move, but it did maybe seem to mark time around the middle to delay Majin’s awakening for as long as possible. One doesn’t really get that sense here, something which is also helped by having more stuff happen right in front of Majin and involving Majin. The main villain Lord Mikoshiba has the bright idea of blowing Majin up this time, and early on too, yet soon after that a boat with him and some others in it is prevented from moving any more forward by the water, as if Majin is already alive but doesn’t possess enough power yet to animate the statue, and someone is found dead impaled by part of Majin. And Majin has a new power – shooting fireballs from ahem between his legs[!]. Overall I think it’s a better movie, director Kenji Misumi, who like the other two directors of this trilogy made some entries in the lengthy Zatoichi series but who will mostly be associated with some of the awesome Lone Wolf And Cub movies, still finding time for some nice, pictorial moments.

Again we open in a forest, though it’s a real one this time, and get hurled into the mayhem immediately as some slaves of Mikoshiba are fleeing their masters but are attacked by some soldiers. After several killings the leader of the soldiers demands that the survivors return, which they do except for a man and a woman who hide then, once everyone else has gone, make a run for it for the nearby Chigusa, where the leaders of the neighbouring village Nagoshi are attending a religious ceremony in honour of Majin. Plans are afoot to get Lord Juro of Nagoshi engaged to Lady Sayuri the daughter of Ikkaku Arai the lord of Chigusa, so things are very good between the two villages. Some escapees from Mikoshiba who’ve been allowed to live in Chigusa for free as long as they work turn up with a thank you gift consisting of loads and loads or rice; it’s really quite a moving scene as some of the ex-slaves try with delight at the acceptance of their present, obviously in Japan it being disrespectful to say “no it’s okay, you can have it”. Some people then go to the island to pray to Majin, while at the same time Mikoshiba and his men take Nagoshi. Jiro manages to escape to Chigusa, but there are soon attacked as well and Sayuri’s father dies in her arms. I couldn’t help but chuckle when his dying words to his surviving men are not to resist because their god will save the day, yet many of them carry on fighting for a bit. And, seeing as the hiding of Juro in Nagoshi subsequently causes so much problems for the people there, one can’t help but wonder if it may have been better for them if somebody had given Juro up.

Still, the tone is dark and gritty, perhaps even more so than before, despite the increased religious element which allows us to witness more of the rituals. And, even when Majin seems to be destroyed by Mikoshiba’s dynamite quite early on, the pace doesn’t slacken as we wait for the statue to walk, though teasing us with an earthquake and a red sky is maybe not quite fair. There’s also a scene where a small boy finds a piece of the statue and keeps it, which seems to set up expectations that this will be an important part of the plot for a while, but these expectations aren’t fulfilled except for the boy to throw it at somebody who’s about to kill someone else and it hit him on the head. The main emphasis is on Jiro, and I guess that’s okay because he’s played by the charismatic Kojiro Hongo who appeared in some Gamera films. He’s not bad with a sword either when Jiro has to fight others, which is quite often. Then, just when all the escaping and kidnapping seems to be on the verge of wearing, Majin comes out of the water in a spectacular entrance, parting the waves Moses-style. No, it’s not quite as well realised as that still hugely impressive scene from The Ten Commandments, but it’s still quite an achievement seeing as Cecil B. De Mille had all the money Hollywood could throw at him at his disposal, and you have to admire Morita for even attempting to realise such a thing. If only it wasn’t followed by a laughable moment where people suddenly release they can escape from cages that it looks like they could have easily got out of from the offset!

This time Majin stomps about when it’s already night time, whereas before it just seemed to get magically dark, while the previously used low angles are employed again. But there are more memorable shots here, from smoke clearing after two walls have been dynamited to fall on Majin to reveal Majin still standing, to Majin smashing down another wall to reveal loads of people fleeing on the other side. Both the model work and the matte work are of exceptionally high quality. Watching the earlier Gamera films on Arrow’s stupendous set of the flying turtle’s adventures revealed their special effects to be only a bit less in quality from the Toho productions of the time, and the Gameras were much cheaper. The Majins had a bit more money spent on them and, even if one takes into account the lower amount of effects work required due to Majin only rampaging at the end, they really shows what Daiei’s technicians could do. Of course we still see human eyes in Majin’s face, but I’ve come to like that now with this second film – Hashimoto, who clearly wasn’t allowed to blink, has quite expressive eyes. Likewise Majin’s island is quite clearly a model but isn’t there such artifice also worthy of enjoyment without mockery and even worthy of praise? What did bother me a little is that the irony of Majin saving the day yet wrecking much of Chigusa is ignored, but I guess that the villagers feel that it’s a worthwhile price to pay, and the final moment between Majin and Lady Sayuri is a tad touching. Cinema is full of improbable bonds between giant monsters and humans yet they often oddly work, and is helped here by Lady Sayuri having found succour in Majin way before he came to life.

A lakeside funeral with the rising son beautifully illuminating a line on the water on the right hand side is one of the film’s more tranquil memorable images, though the much speedier nature of this one means that there’s less time for this kind of thing, and the whole film has a less colourful look for the most part which does sort or suit it. This time the main villain is played in a broader manner by Takashi Kanda; he has a most memorable and rather sadistic death scene which also suggests, as do other moments, a Christian element despite the setting and the fact that Majin is obviously a kami, “holy powers” that are venerated in the religion of Shinto. Akira Ifukube’s score is again has that Godzilla movie sound and style, the composer reworking previously used harmonies, most obviously part of one of the themes from Frankenstein Conquers The World and War Of The Gargantuas for Majin himself, as well as reworking two pieces from Daimajin, but if it suits the film who really cares? The music adds suspense, atmosphere and excitement, so it totally works. I’ve argued against the claim that sequels are rarely as good as the original for much of my life, and Return Of Daimajin is now another film that strengthens my point of view, especially as it’s better than Daimajin which itself was pretty good. It’s as if the makers saw what was working with the first film and ramped it up. The third part of a trilogy can often be trickier than the second part though. Did they drop the ball?

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

Brand new audio commentary by Japanese film experts Tom Mes and Jasper Sharp

Two people rather than one doing a commentary isn’t always better, but Mes and Sharp have a good if serious-minded rappour plus loads of knowledge. However, as with the previous commentators, they don’t chat much about the film in question. I appreciate that there’s not much in the way of production information, but so many major scenes are left unnoticed while the conversation covers other matters. We learn that Mizuno was highly regarded and was invited to be one of Daiei’s prestige directors but turned the offer down because he preferred making period programmers, a lot about a landmark film called Buddha which has been almost airbrushed from movie history, and a hell of a lot about Daiei and Nagata. Some of it interests, while biographies are kept short, but if you want an observant look at the actual film, prepare to be disappointed.,

My Summer Holidays with Daimajin, a newly filmed interview with Professor Yoneo Ota, director of the Toy Film Museum, Kyoto Film Art Culture Research Institute, about the production of the Daimajin films at Daiei Kyoto [33 mins]

Ota tells us how the vengeful god/statue was sometimes part of his life, beginning with a summer job as a boy being a carrier of camera equipment where Return Of Daimajin was being shot, and finishing with making Majin a major part of the 199y Kyoto film festival including building a replica. We hear that Morita collapsed as he finished the second film due to exhaustion which required him to be paired with somebody else for the third, that Yasuda and Misumi drew and used storyboards which Ota actually has a book of, and hear Ota’s views on certain things, such as Daiei caring more about making lasting and quality work rather than making money, which led to their downfall. A nice featurette.

From Storyboard to Screen: Bringing Return of Daimajin to Life, a comparison of several key scenes in ‘Return of Daimajin’ with the original storyboards [4 mins]

A short but most worthwhile extras.

Storyboard Selection

The same eight storyboards as the above; this time you need to use the chapter button on your remote to access the ones after the first.

Alternate opening credits for the US release as Return of the Giant Majin

Trailers for the original Japanese and US releases

Image gallery

DISC THREE – WRATH OF DAIMAJIN [1966] AKA THE RETURN OF MAJIN

RUNNING TIME: 84 mins

The ruthless Arakawa clan led by Toru Abe kidnaps groups of peasant woodcutters to use as slaves to build a weapons depot. One of the strongest log men, Sanpei, manages to escape back to Koyama his village. Near death, Sanpei proclaims they must go to Hell’s Valley to find and rescue their people. However, all paths are under tight security save for the mountain where the Majin statue exists. With winter approaching, the villagers fear angering their god should they trespass over his mountain. Sanpei dies, and no one wants or dares to make the trek. Four intrepid youngsters Tsurukichi, Kinta, Daisaku and Sugi decide to make the precarious trip in secret….

Well they didn’t drop the ball, but they lost control of it a few times. The third film is definitely inferior to the first two, even if one still has to respect that they tried to be significantly different to films one and two while still keeping some of their situations; a tricky thing to do. I guess it’s a little closer to number two than it is number one, with snow replacing water. The most obvious difference, apart from perhaps the religious element being far less strong, is the focus on very youthful protagonists, with four young boys as its heroes and spends much of its length following their progress as they trek across fields, forests, mountains, snow, you name it -and often what are obviously the same locations more than once! However, while Morita Fujiro’s and Hiroshi Imai’s photography is magnificent, capturing an array of natural vistas, very little actually seems to be happening, and even Ishiro Honda, who liked to put extended scenes of outdoor walking in his films because it was a hobby of his, would have chopped a hell of a lot of this footage out. The filming often seems lazy, with quite a few places seemingly missing close-ups. And, despite the fact that you’d probably expect this one to be more aimed at kids as a result, this oddly doesn’t seem to be the case. While the plot has been hugely streamlined to the point that it struggles to fill out the film’s running time, the grim tone is retained and there’s more violence than the other two, with even a fair bit of the red stuff on display.

The opening scene is unusual, and you could say that the filmmakers were cleverly able to say that they began this one with some Majin action instead of leaving it to much later. A mountain and a village beside it is subject to a multitude of natural disasters all together, with volcanic ash rising from the mountain followed by flooding, tremors and a blizzard, resulting in trees being uprooted and houses wrecked, though most of the villagers seem to survive. Some of the events seem haphazardly cut together but maybe we’re observing things happening during different seasons. And, in amongst all this, we see some dark matter forming the Majin and catch a glimpse of one of Majin’s arms and one of his legs, as if he’s just another part of this explosion of angry natural phenomena. Then a voice over tells us that “this story takes place when people used to think that these disasters were caused by an irritable mountain god”, which curiously almost negates what we’ve just seen. Anyway, we find ourselves in yet another peaceful village where a young boy tells of a woman for saying that she’s hungry before a weary, beaten and on his last legs Sanpei stumbles in. He’s one of hundreds of villagers who’s been taken away to slave away for Toru Abe of the ruthless Arakawa clam, and soon dies from his wounds. Lord Koyama wants to send some men to rescue them, but the only way that won’t take weeks is over the mountains, and that’s forbidden and holy, though Sanpei managed it, so three kids decide to make the trek. They tell the even younger Sugi, brother of Tsurukichi the sort-of leader of the kids that he can’t come, but he treks after them anyway. An old woman tells them they “cannot enter here, this is the Majin’s mountain”, but they ignore her and journey on.

And on and on and on, so that tension evaporates despite cuts to worried parents at home and Abe being bossy and cruel. It’s nice though that the seemingly weakest member of the group Sugi proves to be a very great help indeed with his bow and arrow and lightness, but Mori was unable to get good performances out of his child stars, who rarely attempt to emote. An escape attempt is made by Daisuku’s brother, but it doesn’t lead to the expected major action sequence. A dream sequence really smacks of padding, though there is one really fine scene that, even though it seems to be missing a close-up or two, has a real emotional impact precisely because it’s underplayed, even if it’s hard to get one’s head around the idea of these kids being able to build a raft. After a trip down some rapids with speeded up footage and some rather annoying ‘shakycam’, one of the boys slides off a rock and is lost to the water, and one of the others just gazes onto the rock, the camera holding on his face for quite a long time. The shift from real landscapes to sets is very obvious but rather charming, as if it’s emphasising the fact that things are soon going to get more fantastical. But generally this is the Majin film where you may begin to count the minutes till the giant genie awakens to dole out justice to the villains, and you really want him to, because these villains are truly brutal except for three rather incompetent samurai chasing after the kids who fail to see them when they’re in plain sight. Majin’s [it’s The Majin again but I’m sticking with Majin] awakening is proceeded by what the kids call his “avatar”, a black bird who saves them at one point, while blood runs down his face, something we also saw in Daimajin though it’s more effective here.

Majin comes to life surrounded by yellow light which might be lava and might not be; he then seems to disappear before bursting out of the ground saving somebody, so he basically has two opening entrances here. In each film he seems to be more a force for good. In the first, he was indiscriminantly killing left right and centre and only found some goodness right at the end. In the second, he seemed to kill only bad people because of his bond with Lady Sayuri though still destroyed a village. And here, he forms a bond with the kids, just like Daaei’s big jet-propelled turtle [though they don’t ride on his back or anything], so he just kills villains and smashes their fort. These kids aren’t royalty either. Lots of fire and explosions provide a nice color palette amidst the snowy landscape and snowstorm when Majin rampage, though less low shots are used of Majin and he seems to shift sizes which wasn’t something I noticed from the previous two films. Some shots look recycled from the previous features; it appears some of the same effects bits have been done over; or reused, but enhanced with snow effects, such as Majin knocking down a mountain to gain access to the villains stronghold, though we can almost forgive that because here Majin finally uses that sword he’s been holding. The highlight is perhaps when loads of logs are toppled onto Majin, whereupon he just throws them at loads of soldiers, killing loads of them. Some of his killings seem more painful than before, notably a foot crushing where you can hear the bones snapping.

Whereas before blood was hardly ever seen, here people are impaled often with bloody impact wounds showing, Abe smashes a guy in the face with his staff and kicks another into a sulphur pit, and best of all the hawk gorily goes for throats and faces. I’m not convinced that it’s particularly unsuitable for children today considering what many of them get to see, but it’s surprising that a film clearly aimed more at the younger set is like this. But then the Gamera films of the period were, after the first two, extremely goofy, childlike films, yet had some pretty graphic monster violence, so maybe it’s what Daiei liked to do back then. Despite the many landscapes on offer, director Kazuo Mori generally just seems interested in telling the story simply; despite being by far the slowest of the three films, it’s far less keen on giving us lovely or impressive shots. Still, Akira Ifukube provides another eminently suitable score. His Majin music essentially combines elements of his two previous Majin themes, while one piece accompanying mainly traveling scenes was re-used with slight variation in Latitude Zero, and another, a memorably moving piece, had a variation employed in King Kong Escapes. Ifukube maintains the essentially serious and even grim tone. Indeed it’s said tone which is perhaps most interesting about these Majin movies. Even if one takes into account the way that they were made, usually by film number three a monster series was getting a bit silly. Maybe that’s what would have happened if they’d made any more. In any case, even if Wrath Of Majin is a let down, it can hardly be called a disaster.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

Brand new audio commentary by Asian historian Jonathan Clements

I’m going to admit that I’d never heard of Clements before looking at the specs for this set, but I’m very impressed by his commentary which I think is the best out of the three here. And it begins by telling us what was a real surprise to me: Majin was originally though up as an opponent of Gamera! Even more curious is when he criticises the subtitles for not being totally accurate, yet he’s obviously reading different subtitles to what we are! The ones on this Blu-ray are much closer to what he thinks they should say. I guess he was just watching an earlier release of the film. Clements, who doesn’t even really do any biographies, is frequently scene-specific though only sometimes resorts to telling us what’s happening on the screen, tells us that around half the footage was accidentally damaged ruined by the wrongful placing of a stapler so they had to reshoot it which explains the lack of cuts in many scenes, and points out inaccuracies with the use of muskets. Clements, who shows a sense of humour that goes as far as to quote Monty Python, is fully aware of the film’s flaws and seems to have fun pointing them out. A not just informative but entertaining listen. I hope Arrow have him back to do more tracks.

Interview with cinematographer Fujio Morita discussing his career at Daiei and his work on the Daimajin Trilogy [86 mins]

Though a bit disjointed, as if the sections had been shuffled about, this lengthy interview, which begins wonderfully with Morita telling his excitement as a boy when he would sneak into film studios, maintains interest even when he’s not discussing the Daimajin films. As a fan of old school special effects, I was absolutely fascinated by much of it. The best bits are when he watches scenes from the Daimajin films and comments on them, revealing how he did the effects and sometimes saying when he thinks he didn’t quite achieve what he wanted, such as the river parting from Return Of Daimajin being too straight at the top. He explains very technical stuff with ease, meaning that this is an essential watch for those interested in how the world of cinema managed without CGI. Things like a materalising Majin being realised by rubbing stuff onto the negative might sound crude, but any mistake would have required whole scenes to be shot again, and more to the point they look good. He wanted Majin’s second death to be more complex, but time was running out. It seems that Morita really was a special effects genius despite being often classed as a cinematographer, and deserves to be far better known and praised.

Trailers for the original Japanese release

Image Gallery

LIMITED EDITION CONTENTS

High Definition Blu-rayTM (1080p) presentation of the three Daimajin films

All three films have fine picture quality with fine colour balance and realistic skin tones. Some very minor specks and fading are probably only noticeable if you’re on the lookout. There’s aren’t even any especially grainy shots or parts of shots despite all the compositing because of the way that the latter was done.

Lossless original Japanese and dubbed English mono audio for all films

I watched the Japanese language versions but sometimes switched over to the English dubs. Thankfully, these are the dubs provided by American International Pictures who released the films on TV in the United States; as we’ve seen before, Daiei don’t have some weird problem with letting people hear such dubs, unlike Toho. There are later dubs which are probably very poor. These ones are sometimes over-enthusiastic but generally decent as these things go; the voice artists make an effort and have some personality.

Optional English subtitles – Illustrated collector’s 100 page book featuring new essays by Jonathan Clements, Keith Aiken, Ed Godziszewski, Raffael Coronelli, Erik Homenick, Robin Gatto and Kevin Derendorf

Postcards featuring the original Japanese artwork for all three films

Reversible sleeves featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Matt Frank

Like on their ‘Vengeance Trails’ set, Arrow’s special features are all new, which makes this release all the more impressive even though I found the third film to be decidedly inferior to the first two. Majin himself would consider it to be a worthy tribute. These films are fascinating, fun and well made. Highly Recommended!

Be the first to comment