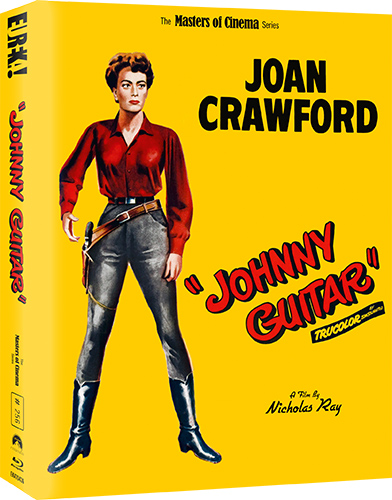

Johnny Guitar (1954)

Directed by: Nicholas Ray

Written by: Philip Yordan, Roy Chanslor

Starring: Joan Crawford, Mercedes McCambridge, Scott Brady, Sterling Hayden

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: NOW, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 110 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

On the outskirts of a wind-swept Arizona cattle town, an aggressive and strong-willed saloonkeeper named Vienna maintains a volatile relationship with the local cattlemen and townsfolk. Not only does she support the railroad being laid nearby which the cattlemen oppose, she permits “The Dancin’ Kid” and his confederates to frequent her saloon. The locals, led by John McIvers and egged on by Emma Small, who both loves and hates The Dancin’ Kid even though he’s in love with Vienna, are determined to force Vienna out of town. The hold-up of a stage and murder they suspect to have been carried out by The Dancin’ Kid offers a perfect pretext, while Emma is out for revenge because the dead man was her brother. McIvers gives Vienna, Johnny Guitar, and Dancin’ Kid and his sidekicks twenty-four hours to leave. But help is on Vienna’s side from a man from her past, the mysterious Johnny Guitar….

Johnny Guitar has a reputation as one of the cult westerns of the ’50s, though I hadn’t gotten around to seeing it until now. That is despite Nicholas Ray, probably best known for Rebel Without A Cause, having made one of my personal favourites of the decade, 1952’s On Dangerous Ground, a really special film to me which my love for I may explain in a review one day. Ray’s work tended to be regarded as decent genre pieces in the United States but was worshipped in France where he was regarded as one of the great auteurs working within the Hollywood studio system. With their frequent outsider characters, disliking of conformity and strong pictorial compositions, many of his films probably play well for modern audiences, and this should be the case with Johnny Guitar, whose basic plot was partly borrowed for Once Upon A Time In The West. It’s a rather odd western that on one level is relatively conventional and on another is strikingly revisionist in its subverting of conventions. It can be enjoyed by those after a simple oater yet is also crammed full of interesting elements. It’s extremely melodramatic, but it also seems to be deliberately heightening said melodrama while still totally involving us with the dilemmas and emotions of its characters. It seems to me to be amazingly feminist for the period and even switches gender roles in places, and along with hints of bisexuality, promiscuity, a slight kinkiness and a full-on criticism of the the House of Un-American Activities Committee [which at the time was trying to force alleged communists to “name names” of other alleged communists] was pretty brave for 1954. Were the censors asleep? It also boasts stunning colour photography by Harry Stradling despite being a very cheap production, a fact you can tell at times by things like us never getting a full view of the ‘town’ except for one very brief partial look.

Star Joan Crawford and Ray were scheduled to make a film called Lisbon at Paramount but rejected the script. Crawford then bought the rights to Roy Chanslor’s Johnny Guitar novel which Chanslor had dedicated to her. The script was credited to Philip Yordan but may have been by the blacklisted Ben Maddow whom Yordan sometimes ‘fronted’ for. Crawford brought it to the cheapie studio Republic Pictures where Ray, having just finished his contract with RKO, had moved to. They wanted either Bette Davis or Barbara Stanwyck for the role of Emma Small, but they were too expensive. Claire Trevor was next in mind but was tied up with another film. Finally Ray brought in McCambridge. She and Crawford disliked each other, something Ray felt added to their conflict on screen, while any technician or actor was supposed to choose whose side he or she was on. Crawford had once dated McCambridge’s husband, Fletcher Markle, which McCambridge needled Crawford about. Crawford and Ray were in the midst of an affair which McCambridge felt was wrong, and Crawford disliked what she perceived to be “special attention” that Ray was giving to McCambridge. Making things worse was that McCambridge was battling alcoholism during this period, though Crawford was also prone to the bottle and at one point drunkenly scattered McCambridge’s costumes along a road. Ray shot some of McCambridge’s footage before Crawford got to the set as Crawford didn’t like the crew applauding one of McCambridge’s scenes. Crawford even threatened to quit if Yordan didn’t come out to the filming location of Sedona, Arizona, to rewrite her part so that it would be bigger than Sterling Hayden’s. Ray later said that when going to work in the morning, he often had his car stopped because he had to vomit at the idea of working with her. All this effort only resulted in critical and commercial failure, at least in the US.

Now every film should open well and immediately involve and intrigue the viewer, but for some reason this seems to be especially important for the western. The one here is a doozy. We see a rider moving across the landscape that appears behind the titles, but he has one anomaly; a guitar strapped to his back, so immediately we’re being shown what we expect but with a difference. An explosion takes place beside him and people run out, then, before we’ve processed what we’ve seen, he watches from a very safe distance the robbing of a stagecoach, and we can’t make out the faces of the people involved. And why doesn’t this guy interfere, ride in and save the day like any hero worth his salt? Why did the explosion take place? These and several other questions stick in our mind and make us want to see more, as the man arrives outside this saloon. He goes in and orders a shot of whisky. The place is empty of other customers and staff members are few. He asks to see Vienna but she says she’ll see him later, and our first sight of her has her clad in black with six shooters standing on a balcony overlooking the main room of the saloon. “Never seen a woman who was more of a man; She thinks like one, acts like one, sometimes she makes me think I’m not” says one of the croupiers, putting into words what some of us are thinking and beginning a subtheme of emasculation. Vienna is busy trying to strike up a business deal but is unsuccessful, us immediately learning that she might often be in control but is also in trouble. A bunch of people then come in carrying a dead body, the townsfolk bearing the dead victim of the robbery victim, and his sister Emily is there and prominent. We’re often asked to sympathise with revenge seekers in films, but this one we dislike immediately as she insists that The Dancin’ Kid did it with no proof even if, in reality, we’d probably understand her anger.

The townsfolk leave but will be back, though the first third largely consists of most of the characters confronting each other and establishing many relationships with clever spatial blocking on the same set, this stage-like saloon that’s built onto a cliff, in one half-hour scene. Johnny is supposedly only there to play the guitar, which he does while backing down from a gunfight, though, when things are riling up between him and outlaw Bart Lonegan, we notice how he catches a shot glass rolling off the bar, showing that he has gunfighter-style reflexes. But it’s Vienna who’s really at the centre of things, and not just because she seems to draw men to her like a flame even though Joan Crawford is more ”mature’ than the norm. She and Johnny were once together but he left because, like most western heroes worth their salt, he didn’t want to settle down. Could their passion be reignited? Their relationship reminded me of the one in Shanghai Express with Marlene Dietrich’s famous line “It took more than one man to change me into Tiger Lily”. “I heard you had a little luck” says Bart to Vienna. “Luck had nothing to do with it” is the reply. Is this implying that she slept with many men for money? But then there’s also The Dancin’ Kid. He’s in love with her, though we’re not sure until near the end if she ever returned his feeling and if an affair took place. And there’s also Turkey Ralston, the youngest of the outlaws, who rather sweetly offers to protect Vienna, though ironically he does the opposite much later. Oh, and let’s not forget Emily, whose obsessive hatred of Vienna seems born out of sexual frustration. Mercedes McCambridge is probably best known for voicing the demon in The Exorcist but she’s just as scary here. The character is over the top but McCambridge sells it.

The time spent on the Johnny/ Vienna romance keeps action at bay for some time and may come across as too overheated in its dialogue for some, but much of the dialogue elsewhere is also this way, often more resembling song lyrics. An early brawl has the camera cruelly cut away from the fighting as soon as it begins to other characters talking. Only after some time are we taken back to what we really want to see. The final third moves outdoors and is full of incident as things hot up and our heroine and hero, the outlaws and a posse where everyone is in funeral garb are soon to properly collide. Some of what we see is slightly more graphic than was the norm for the time; how often did we have a bullet hit a forehead with a shot of said impact? Moments like Vienna’s smile, unseen by the two guys arguing over her but indicating to us that a part of her likes this attention [and yet we still like her], remain in the mind. Was the conventional ending was put in just to soften things?Though by then we’ve had so much to ponder on it hardly matters. Both women wear fetishistic black leather, silk and denim costumes. Both are usually in control of the men around them while the supposed hero is quite passive and not conventionally masculine for the time. Sterling Hayden didn’t know how to ride a horse, play the guitar or shoot a gun. Vienna even seems to remain in control while having a rope around her neck, while Emma insists on leading the posse. Is that the good guys wearing black and the bad guys wearing white, or maybe the other way around? Apart from our central couple and Emma, we’re not always sure who’s good and bad. Pacifism is shown as a good thing; we share Vienna’s disappointment when Johnny becomes his old self again – and this in a western! And the climax parallels McCarthyism really explicitly, with demands to stop sitting on the fence and to name names.

John Carradine has a memorable smallish part but, after the three main leads, it’s Ernest Borgnine [Bart] who made the greatest impression on me. Bart, who “doesn’t smoke, doesn’t drink and is mean to horses”, comes across as thuggish yet seems annoyed when he has to knock someone out. Harry Stradling’s cinematography makes strong use of colour and perhaps reaches its peak when film noir-like blacks resembling bars threaten to envelope protagonists fleeing through an underground cave; it’s a great example of being visually striking yet also commenting on what’s happening. Richard L. Van Enger’s editing includes several deliberately mismatching shots, though this wasn’t new to Ray. Victor Young’s music score is very prevalent and very loud in the mix even by 1954 standards, obviously intended to stylistically heighten matters further. His romantic but slightly edgy main theme has similarities with his one for Samson and Delilah. Well, the men tend not to have much strength and this is even without their hair being shorn. Today, the feminism aspect might be seen by some as more of a joke than anything else, and I think it was partly intended as such, yet it was still daring for the time, and not many films back then had lines like “A man can lie, steal, and even kill. But as long as he hangs on to his pride, he’s still a man. All a woman has to do is slip once, and she’s a tramp!” Even for someone like me who’s sick of the way men often seem to be hated on in current cinema, I loved the overall approach. Johnny Guitar has some plot issues in its final third, such as the unconvincing way the posse gives up the chase, and a few scenes don’t really have the impact that they should. But it’s certainly a film that richly deserves its cult status. I didn’t totally fall in love with it first time round like Francois Truffaut and John-Luc Godard did. But that may happen if I go steady with it for a while.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

Limited Edition Hardbound Slipcase [3000 copies]

1080p presentation on Blu-ray from a 4K restoration of the original film elements, framed in the film’s originally intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1

Seemingly the same 4k restoration used by Olive Films for their Region A Blu-ray release but probably given a new encode by Eureka, this is very fine looking indeed, with the sometimes sophisticated colour schemes really coming through yet the level of grain remaining filmic and even. A few very dark shots have minor crush, nothing to have a problem with. This is a 1954 film after all, and has probably never looked this good.

Archival introduction to Johnny Guitar by Martin Scorsese

The Olive Films has a whole different set of extras except for this, which was on the Universal DVD. They consist of two discussions, three interviews but no commentary, so it’s an equal ‘win some lose some’ situation. Here, a typically enthusiastic Marty describes two highlights and mentions briefly some interpretations, though it could be worthwhile watching the film without it so you come up with your own of the latter. I did.

Brand new audio commentary by film scholar Adrian Martin

One of my favourite commentators opens his track by saying “this is one of the greatest films ever made” and later says “the next four minutes in Johnny Guitar are four of the best minutes ever”. At the moment I don’t agree with either claim, but Martin certainly argues his case very well. He says so much to say that there’s not even much time for biographies or making of information; he just showers the film with love and it’s absolutely great even if you may think, as I did, that he sometimes goes too far. There’s loads of observations on things like staging [I never noticed, for example, a ‘high and low’ visual motif] and editing, a reminder that it all really centres around land, and the suggestion that women, rather than men, are the future in this film’s world.

Brand new video essay by critic Geoff Andrew, author of The Films of Nicholas Ray: The Poet of Nightfall [14 mins]

Both of these chats compliment each other well because they’re so different. Andrews discusses aspects of the film including the idea that Emma’s hatred of Vienna is based on envy rather than lesbian desire, a description of what he sees as mythic qualities like the dusty storm bringing many of the main characters together, and how the story is freudian.

Brand new video essay by Tony Rayns [15 mins]

For his chat, Rayns, usually talking about Asian pictures, goes down a different route and discusses how the film came to be at a time when short term contracts were taking over from long term contracts and the emphasis was more on packages, informs us that the novel and the first script [no mention of Maddow oddly enough] didn’t have Vienna and Johnny having had a previous romance, and discusses the film’s popularity and seeping into popular culture on the Continent.

Never In A Long Time – Brand new video essay by David Cairns [23 mins]

This typically informative piece from Cairns goes into much greater detail about the on-set tribulations, so we learn things like Ray being ordered to “keep Joan Crawford happy”. She’d obviously already become a prima donna. How great it is that we can enjoy watching such people without having to endure their absurd egotism. Cairns goes into the authorship question, the script resembling both a Maddows and a Yordan script, while he also thinks that Ray may have tried to increase Hayden’s role. He also makes some valid criticisms of the plot. Cairns has been somewhat experimenting with his pieces of late, hear adding clay-like characters representing the likes of Ray and Crawford who enact conversations they may have had. I wasn’t a fan, but I’m a bit of an old fuddy duddy with this kind of thing so it’s fair to say that many will find this addition to be enjoyably quirky and provide some freshness.

Stranger – Brand new interview with Susan Ray [29 mins]

Susan was Ray’s much younger second wife and dominates this slightly uneven but fascinating piece which is largely about Ray in his later film teacher phase, along with what Ray thought about Johnny Guitar amongst other things – the tale of how he got a student to describe his experience at a protest is especially revealing of how he thought. We also learn that Ray regretted being dominated by Hollywood, had a dream during the making of 55 Days In Peking about dying and did indeed collapse under mysterious circumstances, and that he disliked Crawford’s phony eye lashes. Interviewer David Cairns also got Tom Farrell and the seemingly ageless Jim Jarmusch to provide further insight. We get a good picture of Ray here.

Alternate Opening Credits [1 min]

Trailer [2 mins]

A Limited Edition 60-page illustrated collector’s book featuring two new essays by western expert Howard Hughes, and an archival interview with director Nicholas Ray [3000 copies]

If you love Westerns you should buy ‘Johnny Guitar’ on Blu-ray. And if you normally don’t like them, you may still really enjoy it. Fans should need no further persuasion; even if you own the Olive Films disc, there’s so much difference in the special features that you might want to buy this one too. Highly Recommended.

Great article but Ben Maddow had nothing to do with this script, he said so.

Can’t wait to see this version. Yordan was called in late and rewrote the « « script » on location.

Thanks.

Well sources seem to vary, even the film experts on the disc seem to disagree as to the authorship of the script. But if Maddow said that he definitely had nothing to do with it then I guess that’s the final word.