The Fifth Cord, The Possessed, The Pyjama Girl Case (1965, 1971, 1977)

Directed by: Flavio Mogherini, Franco Rossellini, Luigi Bazzoni

Written by: D.M. Devine, Ernesto Gastaldi, Flavio Mogherini, Franco Rossellini, Giovanni Comisso, Giulio Questi, Luigi Bazzoni, Mario di Nardo, Mario Fanelli, Rafael Sánchez Campoy

Starring: Dalila Di Lazzaro, Franco Nero, Peter Baldwin, Ray Milland, Salvo Randone, Silvia Monti

GIALLO ESSENTIALS [1965-1978]: On Blu-ray 25th October, from ARROW VIDEO

Arrow have bundled together three earlier releases for this new box set. I was eager to check out two gialli I’d never come across before and rewatch the one I’d already seen. Does this set deserves its title, or are there much better examples Arrow could have included?

DISC ONE

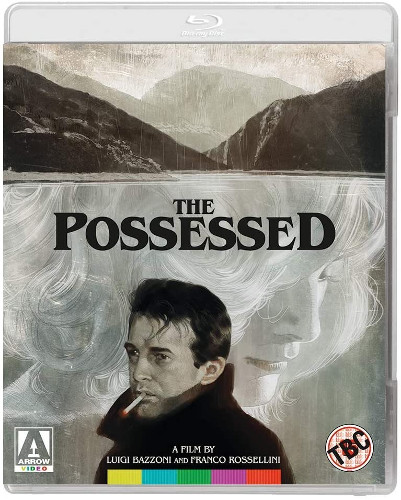

THE POSSESSED [1965]

AKA LA DONNA DEL LAGO

RUNNING TIME: 85 mins

Bernard, a well-known writer, arrives in a small Italian town near a lake to spend his winter holiday and hopefully get going on his new book which will be inspired by all the times he stayed at a certain hotel, going all the way back to his childhood. The place is owned by Mr. Enrico and his daughter Irma, but Bernard is most interested in their maid Tilde who he become infatuated with a year before. However, his friend Francesco tells him that she committed suicide by ingesting poison and slitting her own throat. Soon after that, a photograph reveals that she was pregnant, and when Enrico’s son Mario and his wife Adriana return from their honeymoon, Adriana silently walks around the lake at night. Bernard becomes curiouser and curiouser, but how much of what this haunted man sees takes place in the present or even in the real world….

Every now and again one comes across a film shot in black and white that would lose much of its effect in colour, and the most recent of these for me is The Possessed, whose generic, off-used export moniker is rather misleading and shouldn’t have replaced its far more evocative original title The Lady Of The Lake. Loenida Barboni’s work on this film is simply stunning and is perhaps the most important of the ingredients directors Luigi Buzzoni and Franco Rossellini use to create the dreamlike state which their main protagonist inhabits. Their rather experimental creation is not at all a typical giallo, but then it was made before the genre would really kick into gear. Yes, Mario Bava had already made The Girl Who Knew Too Much and Blood And Black Lace which together form the basic giallo template, but their effect wouldn’t truly be felt until the giallo boom of 1971. Before properly finding its foot, the genre would be taken down some different paths, but I don’t think that I’ve seen any as unusual as The Possessed. It’s based on the 1962 novel La donna del lago by Giovanni Comisso, which was itself based on a real murder case that took place in the village of Alleghe. Two killings, one in 1933 and one in 1946, occurred; the first was of Emma De Ventura, a maid who worked in the hotel Il Centrale and was actually considered to be suicide for many years, the second was of a lady named Caterina Finazzer, but I can’t really tell you any more details because the film does use some of the facts even if it’s not at all a conventional murder tale. The idea of the uncertainty of memory had already been used in The Girl Who Knew Too Much and made a return in a few later films courtesy largely of Dario Argento, but becomes the dominating element here. And Bernard may be trying to solve a crime, but plagued as he is by daydreams, flashbacks and hallucinations, he’s not the most reliable of narrators, and the absence of transitions to these scenes sometimes means that we have work as hard as Bernard in figuring things out. This hugely atmospheric mood piece is quite a rich experience as long as you realise it won’t give you the usual giallo thrills.

It begins with a dumping, done by telephone so that Bernard seems to merge not just with the glass of the telephone box that he’s in but also the city buildings that are reflected on the glass. He hardly does it nicely with excuses like “I feel empty inside” yet even dares to also say “maybe I do love you”. Anyway, now he’s free, and free to pursue the person that he really wants, though why he waits a whole year is a mystery. His thoughts as he drives to his destination are told to us by a narrator, as they are a few times later. Sometimes narrators work in movies and sometimes they don’t, though I’m rarely a fan myself unless its classic era film noir or Apocalypse Now, and the inclusion of one here seems pointless. At the hotel owner Mr. Enrico offers him the biggest room in the place because there aren’t many other people staying, but Bernard would rather return to the room he stayed in last time. Gradually we learn some things about what happened that last time, though it’s done expressionistically as Bernard floats in and out the two time zones so that it sometimes seems as if Tilde is alive in the present, and we’re not sure if everything he sees ever was reality anyway. He developed a huge crush on her and stalked her. He even spied on her in bed with a man, watching through the tiny gap between the door and the doorway. What’s really interesting here is not just the way this is shot, with some shots being repeated several times, but that the identity of the man is hidden the first time Bernard experiences this ‘flashback’ yet is revealed the second. Rather than seeming to be a very lazy way of revealing something that’s crucial to the plot, it’s more an indication of Bernard’s mind. Maybe he blanked out the man’s identity for a while, or maybe he honestly just couldn’t remember?

The hotel is by a lake which exists above the ruins of a city; this detail isn’t important yet it adds an extra element of oddness. Bernard thinks that he can get busy on his new book, though this only what he says to Mr. Enrico; he could be lying. His nights are either interrupted by Tilde’s drunken bum of a father Saverio outside shouting “I’ll see you all in jail”, or he just wakes up and watches Adrianna, the new wife of Mr Enrico’s son Mario, wandering about by the lake she seems transfixed by. Bernard finds out that Tilde was pregnant, yet the autopsy immediately after the finding of her body revealed that she died a virgin. It’s possible that this could be because of a coverup, but who could be behind it? The knife with which she supposedly slit her throat belonged to Mr. Enrico, though of course that doesn’t mean that he was the one who used it on Tilde, and his daughter Irma, who by the way was the person who found the body, says that there’s no way her father could have done something like this. A visit to Saverio proves fruitless, the poor old guy saying “I don’t know anything”. Has pressure been put on him not to reveal things? Adriana seems to want to tell Bernard something, but Francesco seems less keen to help. The nicest person around actually seems to be Irma, who tends to him when he’s not well. Is he being poisoned too? There’s possibly a mutual attraction there, but that sort of thing can’t develop in this environment. The story gives us an unoriginal but still in context surprising revelation concerning one major character which throws us, as the leisurely paced film speeds up for the final act. Unfortunately the resolving is quite pat and makes little attempt to be exciting; we don’t even get to see the murderer’s demise.

I feel that screenwriters Bazzoni, Rosselini, Giulio Questi and, in the first of his many giallo credits, Ernesto Gastaldi, did a fairly good job of giving us the basics of the story while leaving room for style to dominate, though we’re often just as fascinated by Bernard, a most interesting protagonist. Played by Peter Baldwin in a seemingly deliberately detached fashion, he’s an obsessive creep, and we sometimes wonder if he may have committed the murder [or should that be murders?], yet for some of the time at least we’re still behind him in his search for the truth, though we fear for him if he’s ever in danger. He’s extraordinarily passive for a leading character, mostly just an observer who sees things, though most significant events happen offscreen. If you think about it, he’s barely involved in the plot, even though the story is told from his point of view. This heightens the sense of his ‘outsider’ status, though it means that we don’t get much action and certainly no elaborate murder set pieces. Instead we get subtly menacing scenes like Bernard staring [he does a lot of staring] from his window at an outbuilding where Maria is cutting up an animal carcass with a cleaver. Though she only appears in flashback, Virni Lisl’s Tilde, much like Rebecca, hangs over every scene, present in photographs, mentioned in conversations, and always in Bernard’s thoughts, yet she remains something of an enigma when the end credits roll. Performance-wish the person who makes the most impact is Salvo Randone as Mr. Enrico; he’s able to alternate between a genial and sinister countenance throughout. Pia Lindstrom who plays Adriana is Ingrid Bergman’s elder daughter.

The visuals basically constitute a battle between black and white, a battle which is really ramped up during the flashbacks or daydreams which allow Barboni to push the stylisation ever further as silhouettes become characters as they get closer to the screen, black forms strange shapes, and pools of washed out white almost make us shut our eyes. People are often shot from odd angles or with jump cuts. The rundown hotel where most of the key events take place is a highly claustrophobic, almost Gothic mass of rooms, corridors and secrets right beside a graveyard. Inside you can hear the wind outside wherever you are. In fact there always seems to be some kind of natural noise coming in from outside. The recalled sex scenes are totally silent except for the sounds of wolves howling. Combining with the effective aural design is Renzo Rosselini’s eerie music score. Apart from the insistent three note pattern theme that is heard under the main titles, its largely minimalist textures and later blurring with sound effects wouldn’t seem out of place in a film today. I was quickly able to sink into The Possessed‘s mood, though found a tad unsatisfying, not because it was so different, but because there was so much more that I wanted to know – though of course that can also be seen as a good thing rather than a bad the. Less Sergio Martino or Umberto Lenzi than Alan Resnais or Michelangelo Antonioni, it will baffle and let down some, but delight and rivet others.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

New audio commentary by writer and critic Tim Lucas

Richard Dyer on The Possessed, a newly filmed video appreciation by the cultural critic and academic

Cat’s Eyes, an interview with the film’s makeup artist Giannetto De Rossi

Two Days a Week, an interview with the film’s award-winning assistant art director Dante Ferretti

The Legacy of the Bazzoni Brothers, an interview with actor/director Francesco Barilli, a close friend of Luigi and Camillo Bazzoni

Original trailers

Reversible sleeve featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Sean Phillips

DISC TWO

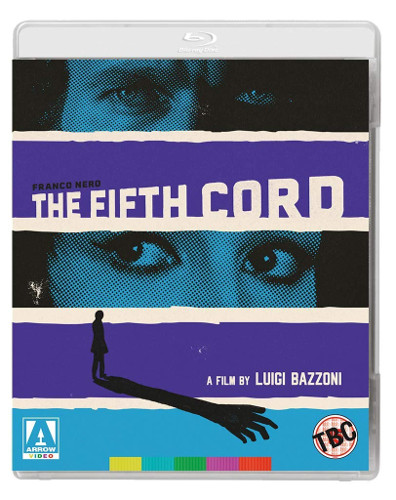

THE FIFTH CORD [1971]

AKA GIORNATA NERA PER L’ARIETE, BAD DAY FOR ARES

RUNNING TIME: 91 mins

Andre Bild is a reporter with a serious drink problem. He has an on-off girlfriend named Lu Auer, but still holds a torch for his ex Helene, who’s been married for the last few years but is currently going through a divorce. When school teacher John Lubbock is nearly beaten to death while walking home from a New Year party Andre was at, Andre, who can’t remember what he did due to being drunk, is the prime suspect, though he thinks it could be someone else who was at the party. Then the wheelchair-bound Sophia Bini, another guest, is strangled in her house with one finger severed and a black glove left as a calling card….

Andre Bild is a reporter with a serious drink problem. He has an on-off girlfriend named Lu Auer, but still holds a torch for his ex Helene, who’s been married for the last few years but is currently going through a divorce. When school teacher John Lubbock is nearly beaten to death while walking home from a New Year party Andre was at, Andre, who can’t remember what he did due to being drunk, is the prime suspect, though he thinks it could be someone else who was at the party. Then the wheelchair-bound Sophia Bini, another guest, is strangled in her house with one finger severed and a black glove left as a calling card….

I chuckled to myself as I typed that last paragraph. This particular killer just had to make sure that everybody knew they were in a giallo by leaving black gloves, and it’s probably not ruining things to say that this murderer must have an inexhaustible supply of the things. The second film in this set from director Luigi Buzzoni [who only made three other films], though this time without the participation of Franco Rosselini, it’s one of the many gialli made largely because of the success of The Bird With The Crystal Plumage, it really is an archetypal genre piece with its murder mystery plot and several killings, even though it holds back on the onscreen violence. It’s also just as or even more artfully photographed than The Possessed, with every other shot constructed for maximum effect. But does this mean that this is a case of terrific cinematography doing its best to make for humdrum everything else? Or are all aspects of the film striking? The screenplay by the director plus Mario di Nardo and Mario Fanelli certainly keeps you interested while being full of the expected ingredients [shady sexual going-ons, blackmail, red herrings etc.] that the likes of Ernesto Gastaldi liked to use, though it doesn’t really play fair with the viewer because it’s virtually impossible to guess the killer based on the clues present, and the explanation for the motive [which probably wouldn’t go down well with today’s sensitive PC lot] is vague to say the least and oddly told to us by Andre’s voice over – though I guess that makes a nice change from the killer confessing all in the typical hysterical fashion. And Bazzoni obviously realised how hard it is to keep up with all the characters [most of whom are sleeping with each other] because when somebody mentions an absent person, the film often obliges by cutting to an identifying close-up. But the film absolutely soars with its suspense sequences which really are expertly crafted and make me wish Bazzoni had become a prolific horror director.

A fish-eye lens roams a nightclub as our killer whispers “I am going to commit murder, I can imagine the thrill and pleasure I will experience as I stalk my victim” in a an almost dreamlike opening that certainly puts the viewer on edge. It’s New Year’s Eve, and we’re introduced to various folk all of whom we assume will be important later. Inebriated Andre is there on his own, as is disabled Sophia Bini, wife to an important doctor who keeps going out at night. Then there’s Isabella and Eduardo who are engaged, plus John, who’s in love with Isabella. Oh, and Helene, Andre’s ex whom he tries it on with to no avail, though he already has Lu and is later revealed to be sleeping with another woman too. John is attacked in a tunnel in the first of the film’s great set pieces full of bleak atmosphere, but isn’t killed, and a guy named Walter and his girlfriend who were nearby making out [people are doing it all over the place in this movie, and usually somebody’s watching too] find him badly hurt. Why? Well, it’s immediately obvious that more than one character knows something about this and isn’t talking. Never mind, Sophia is soon slain in her house, and this is quite a terrifying scene where you are really made to feel her plight, as the disabled lady hears the phone ringing, tries to grab her wheelchair and accidentally falls out of bed, after which she desperately tries to drag herself to the table the phone is usually on – only it’s not there! Then the killer’s disembodied looking hands burst out of the darkness in a really scary image [that’s repeated later] to choke her to death. Soon after, he rings the police up and taunts them in typical fashion.

Andre is determined to solve this mystery, though he’s continually a suspect because he can never remember where he’s been due to his drinking – and boy do I mean drinking – he even drinks straight from a bottle of J & B whisky [what else?] while he’s driving. He nonetheless thinks that he’s supposedly ‘with it’ enough to never need to take notes when interviewing suspects. He’s also bad tempered and violent, even whacking Lu in the mouth after he sees her get into a car with Walter, though in the next scene the two are really playful as if nothing had happened – he hasn’t apologised, she’s not bothered [and doesn’t sport a bruise either]. Is this normal for this relationship? It’s hard to work out how one is supposed to react to this as the film doesn’t seem to comment on this issue in any way whatsoever. Oh well, it was the ‘70s. Franco Nero, with characteristic lack of subtlety, plays this very flawed macho and never grateful character as if he could go all psychotic at any moment [though sadly we never believe that he could be the killer himself], his piercing blue eyes being used to their best advantage. He’s not especially nuanced, but he’s never boring as his character unearths more and more things about most of the other characters while making half-hearted attempts to juggle his love life and sort out his alcoholism. It all climaxes in some fine chasing and brawling in, alongside and up and down a disused building. Of course with Nero doing the chasing it’s hard to think that his quarry is a match for him, but the latter does his best to even things by using whatever’s at hand!

However, where the film truly takes off is when people are being stalked or threatened, notably an old man in the forest with some odd handheld camerawork which doesn’t quite turn out the way you expect it to, and most memorably of all, a young child in a house which has a real charge of terror about it. These scenes are often silent, while cinematographer Vittorio Storaro – who in a way is the real star of the film – continually paints the characters as being trapped by or reflected in their surroundings, and showing them either as silhouettes or continually on the verge of being swallowed by blackness. But then he makes the most of scene after scene. Andre meets with the police inspector in an underground car park and the frosted windows behind the two are reflected in the roof of the car in front and join with the widescreen framing to form a cage. Another conversation they have takes place in front of some prison bars which are also reflected in the car in the foreground. A chat in a car has lights from buildings reflected through the windscreen and all over the characters. One reflection even moves. It’s as if Storaro was desperate to experiment and Bazzoni was happy to gave him free reign. Blue is the main colour but others often intrude in a painterly fashion. Settings are also used very well, like a simple slow pursuit which suddenly comes across a huge number of very old steps, the characters all but disappearing in the expanse. Meanwhile Ennio Morricone’s score, which is perhaps one of his lesser giallo efforts at a time when he working at a phenomenal rate, has some of the usual free-form jazz stuff but prefers to score dialogue rather than action, his main theme, which uses the same accompanying chords as one of his cues from A Lizard In A Woman’s Skin, usually playing quietly behind chatter until we get to a sex party where Morricone’s wordless female vocalist Edda Dal’ Orso is given an actual song to sing, and it’s appropriately rather erotic in flavour. His other main theme is a groovy lounge-like number heard as source music.

The Fifth Cord is very nearly a top grade giallo with plenty to enjoy even if you’re disappointed at the relative lack of bloodshed, though there’s one throat slashing that used to be cut in the UK. Seasoned fans will have fun seeing the slight variations on ingredients that had already become cliche; 1971 really did see a hell of a lot of these films released, after which things would slow down considerably even if the genre would continue to be a major part of Italian cinema. And the sole American in the cast Pamela Tiffin is appealing as Lu while Silvia Monti, Ira con Furstenberg and Rossella Falk [if you’ve seen a lot of these films you’ll certainly recognise the faces if not the names] bring the Euro glamour, though there are also several less familiar performers to spot in this particularly entry in a genre rife with folk who would turn up again and again in the films, often as similar characters. It has its genuinely frightening moments, but it’s most worthy of note for its look which can almost be said to bring German Expressionism into the cosmopolitan, chic ‘70s, Storaro and the set designers skillfully putting together a strikingly sinister and oppressive yet still very modern-seeming universe of pools of darkness, reflections and lines, lines, lines everywhere. And J & B – well, I’ve mentioned it once already in perhaps the ultimate product placement, but both Andre and Helene are also seen pouring themselves a glass later.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

New audio commentary by critic Travis Crawford

Lines and Shadows, a new video essay on the film’s use of architecture and space by critic Rachael Nisbet

Whisky Giallore, a new video interview with author and critic Michael Mackenzie

Black Day for Nero, a new video interview with actor Franco Nero

The Rhythm Section, a new video interview with film editor Eugenio Alabiso

Rare, previously unseen deleted sequence, restored from the original negative

Original Italian and English theatrical trailers

Image gallery

Reversible sleeve featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Haunt Love

DISC THREE

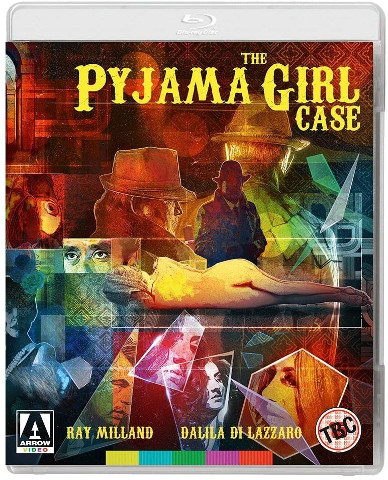

THE PYJAMA GIRL CASE [1977]

AKA LA RAGAZZA SAL PIGAIMA GIALLO, THE GIRL IN THE YELLOW PYJAMAS

RUNNING TIME: 104 mins

Two stories in New South Wales, Australia. The burned, murdered body of a young woman is found on the beach, and the obvious suspect seems to be Quint, a sleazy, grubby man who lives on the same beach, but retired Inspector Thompson thinks otherwise and goes back on the job. And Glenda Blythe, a Dutch waitress and ferry attendant, has three boyfriends and eventually marries one of them, the Italian waiter Antonio Attolini, but can’t stop requiring the company of the other two; older sugar daddy Professor Henry Douglas and Antonio’s Danish friend Roy Connor….

Well you can’t accuse of Arrow of going for the obvious in this set. Despite the first two films in it having the same director, they are quite different, and this one, which reminded me most of a certain cult TV series and its movie prequel more than anything else, is different again, so that really only The Fifth Cord can be considered a typical giallo. Well, if Arrow wanted to get more people into this intriguing subgenre then I guess this was a good idea, though The Pajama Girl Case is very unusual indeed. It comes from a period where the giallo proper had seriously wound down and those filmmakers still making gialli were preferring to vary the format. Like The Possessed it’s based on a real murder case which began in 1934 where the horribly burned and therefore unrecognisable body of a woman was found in a hessian sack in a car on a beach. She’d been badly beaten, an x-ray revealed a bullet in her neck, and she was wearing yellow silk pyjamas with a Chinese dragon motif. Would you believe it, the body was put on public exhibition in the hope that somebody would recognise her. Ten years later the forensic evidence was re-examined and dental analysis revealed the culprit. The film follows the basic details and adds its own possibly explanatory material as it intercuts two stories, one of them a police procedural, one of them the tale of a promiscuous young woman. I reckon that virtually anyone would spot the connection between the tales almost immediately which is why I’m not going to try very hard to conceal it, but there are still a few surprises including a real whopper about an hour in that may take a few moments to adjust to. There are no elaborate murder set pieces to be found here, no black gloves, and the narrative is by neccessity reliant far more on dialogue than action, but the cross cutting keeps the pace up and there’s a desperate sadness at the centre which gradually becomes more prominent. And there’s still a fair bit of sleaze so you exploitation lovers shouldn’t feel totally let down, plus much use of architecture to create a particularly mood.

The introduction to the discovery of the corpse is well done, even though one can be distracted from the almost documentary-like shots of a young girl with a kite and three motorcyclists on the beach by the song with its chorus that goes, “Yellow pyjama the thing that you wear, your yellow pyjama, perfume in your hair” that’s heard over the images. Then both the girl and we get a shock, and boy does the body looks convincingly gruesome. This prompts crotchety, retired Inspector Timpson, who misses the action and has grown bored spending his days tending to his flower garden, to offer his services on his own time. Timpson is an old-school sleuth who follows his instinct and doesn’t think much of the psychological analyses of college-educated cops like Inspectors Taylor and Morris who’ve been put in charge of the case. “They all think we want to bury our mothers” says Timpson, though they all that Timpson is a relic. Timpson is played by Ray Milland, and I must admit that I was a bit disappointed when the screener that we were able to view turned out to be the Italian-language version, not so much because it would have been more believable having all these people in Australia speak English, but because I wanted to hear Milland’s distinctive Welsh tones. Still, his performance, which gives the impression that he was enjoying himself, comes through, and a bit where he says “enjoy yourself” while making the masturbation gesture is an amusing late-career highpoint. The person he makes it to is Quint who he surprised masturbating while watching his neighbour bending over. He’s the main suspect, and is even more so when a child produces a watch, but Timpson follows his own clues, namely some grains of rice and a tag found in the sack with the body. A woman named Patricia names the victim as her daughter, but that’s only to collect an insurance policy.

While all this is going on of course, we have the story of Glenda and her three lovers, the former introduced looking for her knickers after a night of passion. Said three lovers are almost four in a quite strikingly staged and shot flashback, thunder illuminating the white bedroom where a female friend of hers jumps into her bed though the two don’t have sex, and why is the scene in the film anyway? If it was just put in there to add more sleaze, then maybe they should have gone further with it. Glenda quite happily cheats even after she marries one of her men, and is rather selfish and inconsiderate of other people’s feelings. I couldn’t decide whether I liked her or not, or whether we’re supposed to like her or not. This can perhaps be partly laid at the feet of Dalila di Lazzaro who just doesn’t have the acting chops to pull off a role like this, someone who becomes more complex than your conventional giallo free-willed and free-loving female character. And the screenplay by director Flavio Mogherini and Rafael Sánchez Campoy doesn’t seem to quite understand the character they’ve created; I’m not an ardent feminist but this is really one role where some female insight would have helped. As it is, we’re rather baffled by one major thing that Glenda does even if we accept that her mental health is starting to decline, and the uncomfortable nature of this scene, despite being quite subtly shot, is made even more uncomfortable because it feels like said scene was another added for purely exploitative purposes. Yet the climactic scenes of her story do have some power despite director Mogherini soft-peddling the violence that we actually see.

There’s certainly a bit of padding, though boredom is kept at bay because of the oddities. The recreation of the exhibition of the corpse is a several-minute long montage of predominantly gawping male faces while Riz Ortolani’s musical score features what is virtually a proto-techno track. Here, as elsewhere, the film seems to be actually critiquing the predominantly male gaze of these films, a fine case of having your cake and eating it. Despite the way that she lives her life, we don’t like it when men openly leer at Glenda wherever she goes, and she’s not shot particularly leeringly most of the time, but aren’t us straight males really looking forward to the next time she shows some skin? In fact except for Timpson, the men in this film tend to be downright immature in various ways. The Australian setting is interestingly used, the way outdoor scenes tend to have hardly any people about and the use of sleek but sterile architecture looking forward in some respects to Dario Argento’s vision of Rome in Tenebrae. White is often the main colour both indoors and outdoors, while Douglas’s apartment is a particularly hideous example of ’70s interior design. Most of the main characters are also immigrants, and the use of nearly empty outdoor locales emphasises their feelings of isolation and loneliness. The dialogue even makes this theme explicit a few times and the final scene, set very symbolically in a graveyard, really rams it home, not so much saying that Australians don’t receive immigrants with kindness but transmitting the feelings that immigrants have when settling anywhere. While this wouldn’t be unusual in a film made now, it’s strange and rather pleasing to find it in a film of the ’70s, especially in something like a giallo which is usually hardly the most politically sensitive [though it’s sometimes astute] and ‘progressive’ of genres.

Director Flavio Mogherini made no other gialli and from a look at his filmography no other films of real note, yet he gives this rather unique giallo – some would say more of a spin on the giallo – a distinctive feel and, seeing as he also collaborated on the screenplay was clearly trying to make something which would provide more food for thought than the normal entry. Two scenes set in Glenda’s apartment where vivid red and green lighting from a hotel sign opposite bathes her bedroom in colour even seem to wryly rib the style-over-substance approach of many of the better known gialli while paying homage to Mario Bava and Dario Argento at the same time. Of course subtlety is still hard to find, a good example of this being Ortolani’s music. The two songs, “Your Yellow Pyjama” and “Look at Her Dancing” heard throughout in different versions, sung by a lady named Amanda Lear who seems to be channeling Marlene Dietrich of all people, hardly represent Ortolani’s knack at writing tunes well, yet I’ll be damned if they aren’t going through my head right now as I type, even the awful lyrics. That techno track, a lazy harmonica-led piece and a very Goblin-like track also stay in the mind. You may want to listen or buy this soundtrack after watching The Pyjama Girl Case. I may have already have done so. I’m not sure if this was intended, but this film leaves you with some virtually existential thoughts on life and death. I wasn’t always sure if it was that good while I was watching it, but I reckon it’ll stick in my mind for some time. Indeed much like The Possessed, it doesn’t often give you what you want, but what it does give you has its own rewards.

Rating:

SPECIAL FEATURES

New audio commentary by Troy Howarth, author of So Deadly, So Perverse: 50 Years of Italian Giallo Films

New video interview with author and critic Michael Mackenzie on the internationalism of the giallo

New video interview with actor Howard Ross

New video interview with editor Alberto Tagliavia

Archival interview with composer Riz Ortolani

Image gallery

Italian theatrical trailer

Reversible sleeve featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Chris Malbon

Rather than going for three obvious or well known choices, Arrow decided to pick three films that represent both the diversity and the artistry of the giallo, with only one of them being a typical example. Lots of special features also help to make this set Highly Recommended unless of course you own the films already.

Be the first to comment