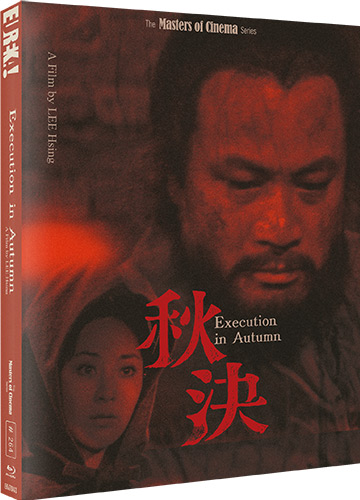

Execution In Autumn (1972)

Directed by: Lee Hsing

Written by: Chang Hung-Hsiang

Starring: Bao Yung-Tang, Bi Hui-Fu, Hsiang Ting-Ko, Wei Ou

AKA QUI JIE

TAIWAN

AVAILABLE NOW: from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 109 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Pei Gang, the sole heir of a wealthy family, has been convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of two men and a woman who claimed he was the father of her child. When he was very young, his grandmother Liao Nai-nai vowed that she’d always get him out of trouble, and she swears that she’ll do the same now, but the deck is increasingly stacked against her, especially when, during a retrial, he admits responsibility for the killings. The execution is a year away, and grandmother carries on doing her best, as well as realising that her failure to discipline him in childhood has led to his immense sense of entitlement and conviction that the rules do not apply to him. Then she thinks of a plan to carry on the family line, but will Gang go along with this?….

I have to say I’d never heard of Execution In Autumn until Eureka’s Blu-ray popped through my letterbox. It certainly wasn’t a film I specifically requested, but of course I was always going to watch it anyway. It’s the favourite work of its director Lee Hsing, who died last year at the age of 91. I think I expected a morally complex look at crime and punishment, and on one level that is what I got, though in a very different way from what I assumed. The starting point may have been the Chinese folktale about the condemned criminal who bit off his mother’s nipple in spite, blaming her for not being strict with him and thereby causing him to turn into the person he became. The wrong actions that many people take can often be attributed to a bad upbringing, but maybe an upbringing that’s far too good can also create bad apples? The big question the story really asks is; was the man right to blame his mother? Shouldn’t personal responsibility play a part? The antihero of Execution In Autumn is like a child. He’s killed three people, but regards his treatment as being extremely unfair, and is unable to understand why any of this is happening to him because good old grandmother should have got him out of this fix, shouldn’t she? But this is also a story of redemption, and these are almost always rewarding to watch on some level. This is quite a unique one, and not just because it’s set in the past, which is kind of odd because Hsing made mainly contemporary-set dramas, and this one could easily have been one too with only a few minor changes. Both downbeat [the film’s title reminds us that the end scene is never in doubt] and uplifting at the same time, it’s often predictable, yet also a highly emotionally engaging tale with fascinating, multi-layered characters.

Opening with a high angle shot of Pei Gang pacing up and down an outdoor cell made of wood, we then cut to two other prisoners being taken away to be executed while Gang forces the door of his cell open and makes a run for it. The titles take place over lengthy pans along portions of a studio forest – and there’s no attempt to disguise the artificiality. Instead the filming revels in it, which is possibly a brave choice, seeing as this is a deep melodrama rather than a fantasy picture. Gang runs pretty well for a person who still has his legs chained together, but he soon runs into Lao Tao the Stockade Governor, and two others jump on him, tie him up and drag him back to the prison where he’s forced to work doubly hard and frequently beaten if he slacks. Grandmother Liao Nai-nai turns up during one of these punishments, and after telling her grandson to “stop pushing that”, offers Lao Tao money to “treat him better”, but the Governor is having none of it. Laio then bribes Pei Sung a local official to engineer a good outcome at the upcoming retrial. Flashbacks show Gang not accepting responsibility for having fathered a child with a woman he was seeing casually [probably one of many], slaying one of her cousins in self defense before killing the other one plus the woman herself where he certainly didn’t need to. He refuses to lie to the court and admits his crime, claiming he was “overcome with rage” believing that the woman and her cousins intended to blackmail him but was otherwise in sound mind when he murdered her because he was sick of being duped and wanted to vindicate his family honour by taking vengeance on those who’d wronged him. Why does he do this? He’s probably so confident that grandmother will get him out of this mess that he just doesn’t care how bad things look for him, but could this be an ironic indication of buried goodness?

Whatever, he’s still full of bravado and defiance, and Nai-nai is still doing her best. She has a year after all, because all executions are carried out in the autumn, in harmony with nature, something explained at the beginning. Sung says that his brother in the Imperial Court may help, but it more seems like he’s just sponging money off the poor lady. We feel even more sorry for her when she visits Gang who knocks the cakes she’s brought for him out of her hands and rages at her for not getting him freed yet. Even more tellingly, when Lao Tao starts to beat Gang for being so nasty, she begs him to stop, saying that “it’s a family matter”. Clearly grandson is always like this to grandmother and grandmother accepts this for being the way things are, though as she leaves she has a revelation and cries out “it’s my fault he’s here”! Flashbacks to Gang’s youth show Nai-nai bringing him up because both mum and dad died soon after his birth, telling him that she’ll buy him a real horse to replace the toy one he had taken away, and promising to always get him out of tight spots. It’s interesting because in many people’s experience [certainly mine], grandmothers are really kind and a haven from the supposed strictness of parents, and this is probably a good thing – unless mother and father are not around, whereupon such spoiling can’t be good for a child if it’s the only upbringing he or she gets. Nai-nai is eventually told that she can’t free Gang, his sentence will definitely be carried out, but she can still ensure that the family line continues, though this requires Tao turning a blind eye. When Gang was very young, Nai-nai adopted a girl named Lian’Er ,and now she wants her to marry her grandson and bear a child for him. The drama soon revolves around the peeling back of layers of three of its four main characters as they increasingly interaction with each other. This is generally so well done that we barely notice the slowing down of pace towards the expected finale – and anyway, such slowing down can be seen as appropriate in context.

Grandmother telling adopted granddaughter to do this this sounds cruel to modern eyes, but Nai-nai genuinely means well and Lian’Er has a strong sense of duty. The latter may sound like a complete pushover, though even that would be understandable considering the largely patriarchal society in which she lives. However, despite accepting Nai-nai’s order immediately, then slaving away in the prison so she can spend a portion of each day with Gang, she soon develops considerable strength as she confronts various obstacles including Gang himself, though it’s a shame that we don’t see her engaging in one confrontation nor carrying out one payback that she mentions. I wonder why screenwriter Chang Hung-Hsiang decided to leave these scenes out which are basically promised by the screenplay, in a film which is as much about her journey as it is about Gang? It could be because it may have diverted attention too much away from Gang, but it’s a bit frustrating. Nonetheless Lian’Er still becomes the strongest character in the movie. As for Gang, he initially doesn’t want to go through with this crazy plan and is dominated by resentfulness, arrogance and anger, but Lian’Er’s purity will have to cause him to melt sometime, surely? Despite having led a life of not giving a damn about anybody or having much in the way of morals, Gang is revealed to be little more than a child, and a child who has a good nature, and who becomes aware of it. The moments when this is revealed are absolutely delightful, especially his final act which completes a transformation which is always believable. And then there’s Tao, who appears keen to be brutal like his guards yet also seems conflicted and looks at Gang in odd ways. The reason for this is eventually revealed and it seems a little over the top for with particular story and film, but, as Tony Rayns explains in the featurette included on the Blu-ray, Taiwanese cinema was dominated by heated melodrama at the time.

Said scene is also the culmination of the subtle performance of Hsiang Ting-Ko which , despite the sheer power of Wei Ou as Gang, the striking luminosity of Bao Yung-Tang as Lian’Er and the intense sadness of Bi Hui-Fu as Nai-nai , might be the very best in the film. Then there’s Gang’s two jail neighbours. One is a common thief who soon reveals to Gang that he often burgled his house and believes in living for the moment, and one is a scholar who’s serving a one-year sentence in place of his elderly father who couldn’t pay his debts and who goes on about the inevitability of death. As well as serving a heavily symbolic function, they also lighten the mood just a little bit without actually making things comedic. Likewise, there are a few minor action beats, not at all of the martial arts kind but well staged anyway, which don’t at all detract from the drama, which is sometimes so absorbing that you may wish the film were longer. I haven’t seen any of Tsing’s other work, but Execution In Autumn, which is resolutely non-specific in time and place, seems not so much Shaw Brothers but rather Japanese in style with its precise framings and obvious sound stages. The main outdoor set obviously had to be significantly redressed four times in order to evoke the changing of the seasons; it’s extremely well done. The unobtrusive camera tends to stay back and just glide along, meaning that when, for example, Lian’Er gets an extreme closeup, the shot has some power, not to mention the use of several rapid zooms into a face in what is Gang’s greatest moment of clarity, which is very sudden.

Unobtrusive is certainly not a word that can be applied to the music score of Ichiro Saito, which is quite western in style. Passages where it becomes extremely forefronted in the sound mix evoke Hollywood-style scoring of some time before. While there are chords of menace and despair and some especially notable use of harps, the score is mostly lyrical in nature, and somewhat softens the darker elements of the tale. For me it still added power to many moments, though some viewers may find it to be rather over the top. The very important character of Nai-nai remains a bit vague and hard to exactly define [which seems to have been intentional], but in general Execution In Autumn is a very fulfilling and emotionally satisfying piece. “We all have to die, but we must die in peace and honour” says the scholar several times, summing up one of the themes, and it’s a theme that’s been employed in the movies a fair few times. However, the idea of loving grandparents being not always right is rather more unusual, especially in Asian countries which tend to venerate their elderly far more than we do here in the west.

SPECIAL FEATURES

Limited Edition O-Card slipcase [2000 copies]

1080p presentation on Blu-ray from a stunning 2K restoration of the original film elements undertaken by the Taiwan Film Institute

Never before available on any digital format until very recently in France from Carlotta Films, Execution In Autumn receives a vivid transfer which brings to the fore its deliberately rustic, brown-dominated look. There are a few occasions where grain may be a little too heavy for some, but better that than any grain removal – this is taken from celluloid after all. Detail is impressive and blacks exhibit no crush.

Original Mandarin audio (uncompressed LPCM)

Optional English subtitles, newly revised for this release

Tony Rayns on ‘Execution In Autumn’ [44 mins]

Well, Rayns also goes into the career of its director and stars, the state of Taiwanese cinema at the time and the situation of Taiwan itself, all of which were probably worth doing seeing as few of us probably knew much about any of this. Even he admits his knowledge of Taiwanese cinema before the 1980’s is limited and much information seems to be missing from sources. I found it interesting that Tsing’s films tended to promote Confucian values which the Taiwanese government also liked to do, though Rayns thinks that with Execution In Autumn he was able to subvert this a bit despite quoting from the film’s press book which mentioned the morally poor state of cinema at the time and that it was trying to bring back “traditional Chinese ethics”. We also learn that Ou Wei took his stage time from a character he played in a successful 1958 film.

Before and After Restoration Demonstration [5 mins]

Visual comparisons of many of the film’s shots in original and restored form, a good reminder of how important these restorations are to anybody who seriously cares about cinema. The picture for this was really faded.

A collector’s booklet featuring new and archival writing

Emotionally and intellectually fulfilling, ‘Execution In Autumn’ is a little known gem. Highly Recommended!

Be the first to comment