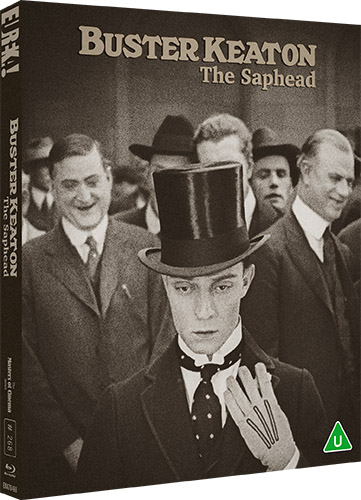

The Saphead (1920)

Directed by: Herbert Blaché, Winchell Smith

Written by: Bronson Howard, Herbert Blaché, June Mathis, Winchell Smith

Starring: Beulah Booker, Buster Keaton, Carol Holloway, William H. Crane

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: NOW, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

RUNNING TIME: 94 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Hugely wealthy New York financier Nicholas Van Alstyne isn’t too impressed with either of his children. His daughter Rose is married to Mark Turner, an unsuccessful broker who’s not just short of money but had a mistress named Henrietta Reynolds, he’s still supporting on the sly. Then there’s his son Bertie, a layabout who’s madly in love with his adopted orphan sister Agnes. He thinks that the best way to impress her is to behave like a bad boy, but this behaviour annoys and embarrasses his father who threatens to cut him off. Bertie has to get a job fast, but the fact that he rarely seems to know what he’s actually doing could be a problem – and then there’s the scheming Mark….

“Saphead”. I didn’t actually know what a saphead was until I looked it up and it translated as, “A weak minded, stupid person”, which I suppose I could have probably worked out for myself if I’d thought about it. The term clearly relates to Buster Keaton’s character in this movie, though I wouldn’t say that it’s wholly accurate; stupid he may be, blundering through because his pampered life hasn’t given him much experience in the real world, but he’s certainly not weak minded, even in the early stages; he most definitely knows what he wants and is trying hard to get it, if in a rather daft manner. This was Keaton’s first feature, and it’s a film that will probably disappoint many unless they have a good idea of what they’re going to get, after which there should be plenty of enjoyment to be had. It wasn’t written as a Keaton vehicle at all, being intended to star Douglas Fairbanks until [well, according to Keaton] he recommended Keaton for his part. It’s fascinating to see the Keaton archetype already partly formed, and the man does get to do a few things that he may have brought to the table himself, but he’s obviously constrained by the conventional melding of humour and melodrama of the piece, an adaptation of “The Henrietta” by Bronson Howard, a popular play first performed in 1887 and later updated by Victor Mapes and co-director Winchell Smith with the title “The New Henrietta”. Saying that though, he performs more than capably in a role that’s a bit straighter than we expect from him in this period, and is always able to focus the viewer’s attention on him when performing with others, his stillness and sheer magnetism contrasting hugely with those around him, though their acting too is very restrained, with little of that heavy emoting. Familiar situations and characters that we’ve seen in so many silent movies turn up, but all periods have their conventions, and it’s probably worth remembering that some of the genres we know today either didn’t exist or were still being created, with westerns, flat out comedies and the odd historical epic being the only major alternatives to melodrama.

The titles are cute, profiles of the characters appearing in mirrors looking at and even emoting with each other; nice matte work here. We’re first introduced to Nicholas Van Alstyne and his “very private secretary” Mr. Musgrave in their veritable castle in the middle of Wall Street, receiving “Jim Hardy from Arizona”, who’s brought some gold from the Henrietta mine, so therefore a deal is going to happen. Meanwhile his son-in-law Mark Turner, whose, “Morning mail as usual was all bills and no business”, receives a girl who has a letter for him which reads, “I’m destitute and very ill, I must see you” from a thorn in his side, a poor woman he knocked up and then dumped – okay, we only learn that she has a child much later but it will probably be very obvious to almost any viewer what the situation is. He doesn’t seem particularly bothered about Henrietta’s situation, just telling the girl to inform Henrietta that he’ll send some money in a few days, then enlists an aide to retrieve her letters [which he presumably sent back to her] and I guess destroy them. Unknowing wife Rose shows up and of course offers to speak to her father about giving Mark a commission. Keaton doesn’t appear for a while, and his character Bertie is first seen in the lounge eating a lavish breakfast in the afternoon, because he’s never home before three in the morning, with a servant bringing him a choice of jackets and boutonieres to wear for the [rest of] the day. He’s leading this “fast life” because of a book he’s reading called “How to Win the Modern Girl”, which claims that ladies now tend to go more for the bad boy type. All this is introduced with cutting between these situations which is surprisingly sharp for the time, with sometimes just a few lines of dialogue being spoken before we cut to somewhere else, as if directors Herbert Blache and Smith, plus their unnamed editor, were experimenting a bit, though this lessens after a while.

Bertie goes to meet Agnes at the train station, but it’s the wrong train station. He then goes to a casino and she despondently sits with her father, thinking Bertie doesn’t care for her. At the casino Bertie accidentally wins $38,000. When he finds out a single gambling chip is worth two grand, he examines one and asks the dealer with comic earnestness, “What’s it made of?” Then the place is raided, and Bertie practically begs a cop to arrest him and even tries to hop into the paddy wagon, but he doesn’t even succeed in that. He goes home and confesses his love for Agnes to sister Rose, and she feels the same way. Old Nick doesn’t exactly approve, but he wants the best for his dear adopted daughter, so he cuts Bertie a million dollar check and tells his he and says that he’ll bless the union once Bertie starts working and makes a name for himself. Our hero promptly gets to it, purchasing a seat on the stock exchange for $100,000, and presenting Agnes with an engagement ring which is wrapped in several different layers. In fact he also buys five wedding rings so he’ll have one in each pocket for the wedding in case he has trouble at the crucial moment. Both the pace and the interest slacken a bit around the middle section, as the attention is mostly focused on this couple and their father, something which is especially a let down when the film was really beginning to seem like a more typical Keaton-starrer for a bit. However, nasty Mark then proves himself to be very nasty indeed. Henrietta dies and asks Mark to take care of their child, so Mark says in front of many that the child actually belongs to – well, I’m sure you can guess. Mark then gets up to even more villainy. Can Bertie save the day?

Well, we know that things will eventually turn out okay, but it’s a fairly solid story of its kind and does allow for a frantic and fairly large-scale climax with Bertie grabbing people who are crying “Henrietta”! and saying “I’ll take it”, for reasons that will be obvious if you watch the film, though I found funnier the scene a short while before when Bertie first shows up in the world of Wall Street and thinks that the others knocking his hats off is a game, even going off to buy some more hats, and this section also has the one big Keaton stunt, hurling himself over a crowd of people to land sitting up against a wall. There’s an obvious cut in the middle of the scene, but of course with films of this vintage it could just be because of damaged or missing frames. He’s able to add some little comic bits of business elsewhere, most notably when he’s going down some stairs. He walks down one flight before being so jolted by being shouted at that he slides down the next flight before recovering and going down the final flight the normal way. Fans will still love the way he goes through every situation somewhat bewildered, with his deadpan expression and his eyes. We know that Bertie is a really decent sort, so we’re totally behind him, who’s discounted by everyone in classic comedy style, and feel really sorry for him when, after disaster has struck, he goes home and is welcomed by servants as he sits sadly at the table full of food and drink that he should have been sharing with his bride. Keaton’s spoiled clueless young man, his being thrust into the role of the fall guy by the actual bad guy, and a prominent father-son relationship are but three things he would repeat in later features where he would have much more creative freedom.

Playing Nicholas is William H. Crane, who played the same role on stage twenty-two years before. He’s perfect as the exasperated old man who’s probably got where he is by lots of hard work. Beular Booker and Carol Holloway both make a strong impression as the two chief ladies of the piece, though we do eventually meet poor Henrietta, in the form of the uncredited Helen Holte, in a very sad scene that probably should have been longer seeing how important it is to the narrative. In fact it feels as if screenwriter June Mathis and Winchell Smith, in adapting the play, and directors Smith and Herbert Blache, had to rush through this subplot. I wonder if the fact that we never see the baby, and it’s only referred to as writing in a letter, was because of America’s moral guardians of the time? After 1934 it’s doubtful we’d have had a mention of the baby at all, seeing how strict things got. Blache and Smith, along with cinematographer Harold Wenstrom, seem to be confident enough with the material to allow odd touches like a still shot of people with their arms outstretched while the words “Henrietta” appears several times above their heads. The name Henrietta curiously exists as a dancer whom Bertie has a photograph of, the mine, and of course Henrietta herself. It’s a nice touch, and those who complain about its unbelievability might be missing the point, it probably wasn’t intended to be plausible at all in a story that contains other big coincidences. One lovely moment has Agnes and her father despondently waiting up for Bertie while a fire blazes. She looks at the fire, and imagines Bertie drinking with another woman on the other side of the fire; was this actually shot through the fire, as I couldn’t detect any matting? Another nice touch is the way locale changes are sometimes signified by a painting which symbolically links to the main action or a particular character; an introduction to Agnes shows a lamb away from the herd.

The Saphead isn’t anywhere near classic Keaton but it’s undeniably a pretty important transitional work in his career. Even though its overall format isn’t something Keaton would go for, it’s crammed with things he’d reuse and develop in later works. And – I thought I’d save this to last – he smiles, this being the only time he did this until the sound days aside from one very early short. and he does it twice. Well, one of those is more a half-smile, but still.

SPECIAL FEATURES

Limited O-Card Slipcase [2000 copies]

1080p presentation on Blu-ray from a restoration undertaken by the Cohen Film Collection from a first generation nitrate print

Kino Lorber released The Saphead in 2021 on Blu-ray in North America, but Eureka’s version uses a different 2020 restoration. Proceeding text tells us that, while two other versions in addition to the original print were looked at, none were different in terms of editing. The picture is marvelous considering the film’s age. Grain is pretty even, and textures and blacks are especially impressive. A few vertical scratches can be seen but they aren’t major. Very impressive.

Score by Andrew Earle Simpson (presented in uncompressed LPCM stereo)

Kino’s version had a score by Robert Israel. Eureka’s has a different track. I like Israel’s work but Simpson’s is more than good enough. It bounces along, its recurring themes and motifs memorable enough and forming a coherent musical experience. Some jazz sonorities are heard in the casino scenes and some great frantic action stuff for the climax.

Brand new audio commentary with film historian and writer David Kalat

Kalat’s typically very clear and enthusiast [he clearly loves Keaton’s films so much] track largely amounts to a defense of a picture which, despite being made between his first [which he shelved] short High Sign and his second One Week, is unfairly ignored and criticised. He [rightly in my opinion] says that it plays much better if you approach it from different angles to the normal critical ones. He goes into some detail about which things Keaton re-used and developed such as two people missing each other at a train station, tells us that Fairbanks had already played Keaton’s character in a different film, and most interestingly points out an actress who’s only in one shot despite her character, a love interest for Nicholas, having been important in the play and even appearing in scenes she’s absent from in the film.

Complete alternate version of The Saphead, comprised entirely of variant takes and camera angles [75 mins]

I only flicked through this edit, which was also available on the Kino. In the silent days films were often shot twice or more with the extra versions sold overseas. Therefore differences are almost always minor, yet noticeable if you compare the movies side by side, such as a slight change in timing or manner. The shorter running time is due to the inter-titles being relegated to flashes, because the distributors for other countries would then make their own titles and know where to insert them. The picture quality is inferior, with more print damage and obvious missing frames, but certainly not bad.

A Pair of Sapheads – featurette comparing the two versions of the film [7 mins]

This is also from the Kino, which means that the footage from the American version is tinted as per the version they used. Side by side comparisons are very useful in showing us the differences.

Bubbling Gravity – Brand new video essay by David Cairns [21 mins]

As usual Eureka have produced their own featurette. Cairns repeats some information we hear on the commentary [or vice versa depending on which was done first], but we also learn a lot of other stuff, such as details about the two directors [Smith actually directed the actors while Blache was hugely misogynistic to his wife who worked with him], while Cairns also wonders if the actors around Keaton deliberately played more subtly because Keaton’s subtle performing style. We also hear that Keaton explained said his lack of smiling was due to concentration, which can be applied to his characters as well. Cairns doesn’t like some of the melodrama which Kalat and myself don’t mind so much, but this is nonetheless a typically perceptive piece.

The Scribe (1966, dir. John Sebert) [29 mins] – In his last film role—produced to promote Construction site safety—Keaton plays a janitor who in his attempt to educate workers on safe practices, causes more accidents than he prevents

Well it’s hard to get used to the 7o-year old Keaton after watching him at age 24, though he does still do some cool stuff here which recall the glory days, such as coming out of a room and the doors on rooms either side of him fall off, narrowly missing him. The faster running and high-up footage was done by a stuntman. Keaton plays a cleaner who pretends to be a reporter investigating construction accidents, going all over a site with a list of safety rules but engaging in and causing mishaps. Though explicitly educational, there are some decent laughs here and Keaton is still mesmerising. The final scene is very poignant because it repeats an Arbuckle gag, reminding us of Keaton’s beginnings. Picture quality is average but, as the director says in his commentary, copies tend to be really poor. These were also on the Kino.

Previously unheard audio commentary on The Scribe with director John Sebert (recorded before his death in 2015) and writer / silent cinema aficionado Chris Seguin

This fascinating track tells us all we’d like to know about Keaton on set. He was game for most things and invented a lot of stuff, though his wife would do her best to restrain him and he was happy to train his stuntman to be like him. He often said the film wasn’t funny enough, perhaps forgetting its main purpose. Sebert recalls with great fondness.

Buster Keaton in conversation with Kevin Brownlow – a 2-hour audio interview with Keaton and film historian Kevin Brownlow from 1964 [120 mins]

I opted not to listen to the audio interviews, the first two of which play over the film, due to time.

1958 Buster Keaton Interview [90 mins]

Buster Keaton: Radio Interview [8 mins] – a rarely heard interview with Keaton

A collector’s booklet featuring new essays by journalist Philip Kemp and film writer Imogen Sara Smith, as well as an appreciation of The Saphead by film writer Eileen Whitfield

“The Saphead” has been given a simply superb release. It must have its fans at Eureka who have done their best to rehabilitate a film which is more important and indeed fun than seems to be the general opinion, as well as treating Keaton fans along the way. Highly Recommended!

Be the first to comment