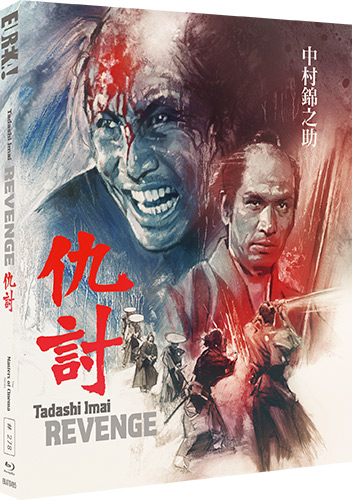

Revenge (1964)

Directed by: Tadashi Imai

Written by: Shinobu Hashimoto

Starring: Kinnosuke Nakamura, Takahiro Tamura, Tetsurô Tanba, Yoshiko Mita

AKA ADAUCHI

JAPAN

RUNNING TIME: 104 mins

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY: 19th June, from EUREKA ENTERTAINMENT

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

Ezaki Shinpachi, a low-ranking samurai with no prospects, gets into an argument with Okuno Magodayu, a high-ranking officer, resulting in an illegal duel and Magodayu’s death. To prevent more bloodshed, the judges declare that both Shinpachi and Magodayu were insane at the time of the duel. Shinpachi is then exiled to a local Buddhist temple and branded a madman. His girlfriend Ritsu wants to accompany him in running away, an idea supported by the Abbott, but Magodayu’s brother Shume wants to kill him, so shouldn’t Shipachi stay and do the honourable thing? Unfortunately, the situation then goes from bad to worse, in an environment where the appeal process protects the strong clans and punishes the weak, and judgments favour whatever will increase the retainer fees from the government. It’s small wonder that Shinpachi begins to lose it for real….

“Bushido” aka “the way of the warrior”, was a code, loosely related to the European concept of chivalry, which governed samurai attitudes, behaviour and lifestyle, combining sincerity, frugality, loyalty, fighting prowess and honour until death. However, Revenge does something which I found quite remarkable; it exposes it as a fraudulent ethos which is frequently abused by people for their own interests, in a social order where the driving factors seem to be greed and saving face. It’s a very tragic tale, almost painful to watch as its hero gets further into trouble simply for defending himself, in a world where in some cases you’ll be better off being killed in a fight than slaying your opponent, a world where a supposed moral code can deprive a fairly decent human being [I incorporate the word “fairly” because there’s one scene where he doesn’t seem to be very decent but let’s set that aside for now] of his station, identity and sanity. Not being much of an expert in samurai movies – I’m afraid that my knowledge and experience doesn’t extend much beyond Akira Kurosawa, Lone Wolf and Cub and Zatoichi – I was interested in seeing more and was therefore very keen to see Revenge – but writer / director Tadashi Imai’s film turned out to be rather different from what I expected, despite being scripted by Kurosawa’s most prolific screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto who scripted his two masterpieces Seven Samurai and Ikiru among others. Very low on the expected action, with the first of its three fights not even being shown, it nonetheless managed to impress really quickly, first and foremost because it was telling a very good story which right off the bat had me involved. It’s actually part of a subgenre I was previously unaware of, called the zankoku jidaigeki (cruel jidaigeki) film, where criticising the feudal system and the Bushido code in downbeat scenarios is what it’s all about. Imai, not a filmmaker I’d known of before but one I’m now keen to explore, also two other films of this nature, but I’d be very surprised if they’re as powerful as this one.

There’s one important aspect to the storytelling which needs mentioning right away before I get into the meat of this review, as it’s not one that always worked for me. We open with the preparations for a duel, before flashing back to show how this duel came about, a device that comes off really well in this instance, but later moving around in time gets a bit confusing. I tend to love when this kind of thing is done in a film, and I’m somebody who’s sat through the horror that’s the chronological [plus heavily shortened] recut of Once Upon A Time In America, a film in which time and memory are the most important themes, but here it’s sometimes hard to work out when we’ve flashed forwards or backwards, exactly where we are in time. Anyway, we start off with the building of a fence. Two old guys come along, prompting the exchange: “What’s going on here then?”, “You don’t need no fence like that for a horse race”, before the two are shooed away. In actual fact the fence, which has to be built in exactly the right way with exactly the right measurements, will form the place where inside a duel will take place. The lead-up to the encounter really builds up the suspense with a series of establishing shots, a pan down from a notice on a roof informing passers-by of the duel, its participants, the time and the place, and short scenes of the two combatants ensuring that each one of them is ready and “will not do anything cowardly or underhand”, Shinpachi being on his own while Magodayu has somebody with him. Why is all this taking place? Somebody admits that it’s because of “a trivial matter”. We see Magodayu accusing a soldier of not polishing a spear properly, then Shinpachi telling him that “a quick polish and they’ll be fine” and that he’s being “needlessly harsh”. It escalates, and what’s most interesting is that Magodayu turns away twice but Shinpachi, to the concern of his retainer who tries to restrain him, won’t let it go. Yes, Shinpachi is our tragic hero and Magodayu was being both arrogant and picky, but if Shinpachi had let it go than all the crap that then happens to him wouldn’t have taken place.

Shinpachi wins, with Magodayu soon dying of his injuries. However, such fights are actually illegal, and the Okuno clan is one of the most powerful around. Losing face would be very bad, for them, which is why Magodayu’s body is transported down quiet roads at night so it’s not seen. One of Magodayu’s two brothers Shume wants revenge and is worried about the clan being called cowards, but the original purpose of a vendetta in Bushido was to save heirs that are now in jeopardy due to a killing, so the clan head insists in asking the authorities what to do. The two fighters are called insane and Shinpachi placed in a monastery and told not to come within seven miles of Kobe. However, Shume won’t rest. After all, killing a mad dog is justified, isn’t it? Shinpachi is visited by his aunt Michi and his sweetheart Ritsu. The Abbott thinks that they should run away together, and that does seem like the most sensible option, but her father might have something to say about that, and after all Shinpachi has already won one fight, hasn’t he? Despite this, we still want Shinpachi to win against Shume, which indeed he does. However, this just makes him more of a liability, and not just for the Okuno’s, with others wanting an end to it all and the authorities increasingly embarrassed by the issue. While he wasn’t mad before despite being branded as much, Shinpachi begins to get that way, despite his friendship with the youngest of the Okuno clan Tatsunosuke, and considering what he’s asked to do next, this is hardly surprising, though he’s not the only person in the story ordered to do something that angers and hurts him and goes against things such as pride and morality, despite the code of Bushido supposedly governing everything. Indeed this other character is actually forced to do what he’s told and therefore perhaps has it worse at the end. What with conspiring forces willing to do everything in their power to have things go their way, no matter how underhand, and almost everyone no matter how close wanting Shinpachi dead, not to mention a government which is most interested in how much money fortunes can leave, we can predict elements of the outcome, but the climax, taking place in front of a jeering crowd, still evokes some strong emotions.

Revenge doesn’t say much that’s nice about society, where everyone has to play their ordained, hierarchal role, though its theme of the sacrifice of the individual to a strict social system doesn’t prevent it from allowing sympathy for its characters, even its bad ones. Shume, for example, is a person whose thirst for revenge we can understand, while Okumo retainer Niwa Denbei is only performing his duty when he rigs a duel in a hugely excessive way so it can only have one possible outcome. Of course we can trust Hashimoto to write characters who have dimension. Most of them are trapped in some way, except for of course the supremely arrogant Sheriff whose drive for more and more money allows him to not just allow but to also openly enjoy fights that aren’t even legal. What a horribly slimy piece of work he is! As for Shinpachi, maybe it’s his pride [which can be perhaps better called “self respect”] that lets him down most? The Abbott is a great character, wordly, humorous in a sly way, and realising that going against what’s expected or just plain pride aren’t always the most sensible options. Even though a lot of attention is paid to ritual, the two fights are messy, frenzied and come across aa being very realistic. That’s not something one can really say about the very obvious sets, yet it’s amazing how much tension Iwai is able to create from a screenplay which largely consists of dialogue, some of it being out of necessity variations of what we’ve previously heard, while also having cinematographer Shunichirô Nakao shoot the majority of the film in a lingering fashion. For example a person on a horse takes ages to disappear behind some trees, though that’s not to say that there aren’t moments of strong editing from time to time, notable the use of jump cuts right at the end to enhance the effect of a moment. Character positioning is often very meticulous.

Lead Kinnosuke Nakamura initially seems rather over the top, albeit in the manner of many Japanese performers, especially in period pieces, of the time. Yet as the film progresses his performance becomes more and more affecting and convincing. One of his best scenes is when he’s outside, training for a fight with his sword in a storm. He fails to properly sever a bamboo tree which then falls on him. What’s evoked well here is the sheer pointlessness of what Shinpachi is doing, an impotent single person against an all-powerful system despite his strength and his prowess as a swordsman. Yoshiko Mita is quite layered as Mitsu even though the character is rather thin. Her subplot leads to a rather unsavoury scene which is hard to know how we’re supposed to react to. Shinpachi finds out that she’s been told to marry somebody else, so what does he do? He drags her into a barn and rapes her, an act that we obviously don’t see, the camera discreetly retreating to the empty barnyard for a considerable amount of time in a rather agonising moment, a fine example of the power of subtlety. Then we cut back to the aftermath and Ritsu looking like she’s just had a good time and asking if they can get married [no I’m not joking]. Shinpachi’s treatment of Ritsu is probably realistic for the time and place, and may not have even been considered as a particularly bad thing, so it can be justified even if it lessens our sympathy for Shinpachi. However, it’s awfully hard to totally accept her manner afterwards.

Despite that, I liked virtually everything else in Revenge, a film that provokes the right kind of anger as it hammers home its main theme with considerable intelligence. Most moral codes are probably in essence good, but are so easy to abuse, yet maybe – just maybe – society needs to be rigid, needs for people to know their place, in order to function properly? Revenge causes the viewer to think as much as it causes the viewer to feel sad and angry.

SPECIAL FEATURES

Limited Edition slipcase featuring artwork by Tony Stella [2000 copies]

1080p presentation on Blu-ray from a 2K restoration of the original film elements

Deep blacks and vivid detail populate this restoration which shows signs of damage, most notably at the beginning where excess grain and tears are in evidence, but whose flaws are no doubt due to the state of the original elements.

Uncompressed original Japanese mono audio

Newly translated English subtitles (optional)

Brand new interview with Tony Rayns [22 mins]

As is sometimes the case, Rayns spends so much time talking about background, be it the undoubtedly interesting career of Imai who seemed to alter his style depending on what he was making was about, other films of this subgenre, or Japanese politics which does relate to why these films appeared in the ’60s, that he doesn’t say much about the movie in question, though he clearly admires it, finding it authentic while agreeing with me about Nakamura’s limitations as a performer. It’s interesting that Toei made it because they wanted to go more upmarket and enter a movie into the 1964 Arts Festival.

Brand new video piece by Jasper Sharp [10 mins]

A collectors booklet featuring new writing on the film

Sharp seems to ensure that he looks at different stuff to Rayns, beginning with the claim “we’d have a different view of Japanese cimema if Iwai was better known”, but it makes sense seeing as much of his work seems to be rather different from what we Westerners might consider to be the norm, though some of it wasn’t released in the United States for political reasons, such as a character suffering burns from Hiroshima. He seems to like sticking up for the unlucky, the poor, the individual against the system. Sharp talks about his major works. Apparently many critics consider his film to be little more than polemics and stylistically limited, but I know that I want to see more.

Though not what I expected, I’d say that “Revenge” was essential viewing for Samurai movie lovers, though it’s actually much more than that, its central narrative and themes being ones that one can still apply in today’s time. Highly Recommended!

Be the first to comment