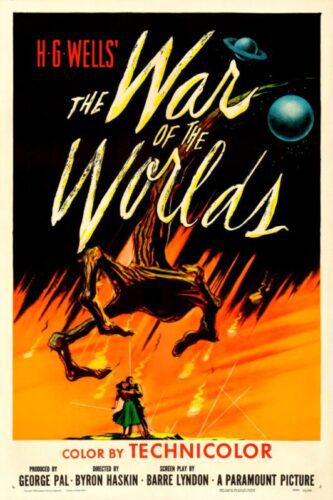

The War of the Worlds (1953)

Directed by: Byron Haskin

Written by: Barré Lyndon, H.G. Wells

Starring: Ann Robinson, Gene Barry, Les Tremayne, Robert Cornthwaite

USA

AVAILABLE ON BLU-RAY REGION A, C, DVD AND DIGITAL

RUNNING TIME: 85 mins

REVIEWED BY: Dr Lenera

In Southern California, well-known atomic scientist Dr. Clayton Forrester is fishing with colleagues when a large object crashes near the small town of Linda Rosa, to which he heads and meets USC library science instructor Sylvia Van Buren. Later that night, a round hatch on the object unscrews and falls away. As the three men standing guard at the site attempt to make contact while waving a white flag, a heat-ray obliterates them. The Marine Corps later surrounds the crash site, as reports pour in of identical cylinders landing all over the world and destroying cities. Three Martian war machines emerge from the cylinder. Sylvia’s father Pastor Matthew Collins attempts to make contact but is disintegrated. The Marines open fire, but are unable to penetrate the Martians’ force field, then the aliens counterattack….

I don’t think there’s yet been a definitive screen version of H. G. Wells’s still thrilling novel, and maybe there will never be one. Any potential adaptors have to make one very important decision right away; do they set it in its accurate Victorian time period or in the present day? The two movie versions did the latter, and did well with it, though I personally yearn to see the story happen in the time it was written [I’m choosing to forget that godawful TV miniseries that ruined Christmas a few years ago]. For a start we could have a recreation of one of the most exciting and tragic parts of the novel, the “Thunderchild” sequence where a heroic ship protects an evacuation fleet to Europe and even destroys two tripods before eventually succumbing to the invaders. To be honest I wasn’t too keen on this 1953 version the first time I saw it in the late ’70s. By rights it ought to have totally thrilled this eight or nine year old, but the trouble was he’d been listening to the Jeff Wayne album adaptation [which was basically the novel with songs] for the last couple of years, so he found a lot to complain about. Why were the Martians and their machines different? I was hoping for the tentacled creatures and the tripods and got inferior substitutes. Where was the red weed? Said weed was one of the best parts of the album, the earth’s surface being transformed into that of Mars. Why was there no “Ullah” war cry? Why was the plot changed so much? At least the scene in the house was there, sort of, and it was scary. The ending was right, but – honestly – this was not The War Of The Worlds as I knew it. Of course I later changed my mind. It is, after all, one of the most exciting of ’50s science fiction films, done and dusted in 85 minutes despite its scale. In terms of spectacle it remains pretty good too, though budget cuts did have an effect, there are clumsy aspects, plus there’s one element that producer George Pal put into the story which annoys the Doc considerably.

Wells’ still thrilling novel was notoriously turned into a radio play in 1938, directed and narrated by Orson Welles. The “breaking news” style of its first half incited a panic by convincing some listeners that a Martian invasion was really taking place, though the scale of this was exaggerated by the press. The film rights were purchased by Paramount in 1925, and Cecil B. DeMille was to direct a version that year; for three decades he was still interested but few others were. Sergei Eisenstein who was intrigued for a while, and in 1952 Alfred Hitchcock became interested, while Ray Harryhausen sent test footage of an animated Martian to Paramount; he wanted to set the story in the Victorian era, but got no response. DeMille, who still had the rights, eventually gave up and handed control to George Pal, who chose Byron Haskin to direct. Pal wanted the audience to put on 3-D glasses when people put on goggles an hour or so into the film, the rest of it being in 3-D, but Paramount, as they had done for Pal’s When Worlds Collide, reduced the budget – science fiction was considered more for ‘B’ movies, after all. Two days into filming, production was briefly halted when it was discovered that filming rights were only for a silent version; this was quickly resolved. Corona, California doubled for the fictitious town of Linda Rosa, and the hills and main thoroughfares of El Sereno, Los Angeles, were also used, though sets were mostly used. The heat ray was created by burning welding wire with a blowtorch forcing the sparks off of it. Its sound was done by attaching a slightly off-center wooden disk to a power drill, running it at the fastest speed, and touching it to a string on an electric guitar. The film was a huge hit and, despite the many changes that Pal made to the book, with the human drama almost entirely different though some of its big scenes did make it in, Wells’ estate were happy and let Pal choose another Wells property to film; he picked The Time Machine, which became in my view his greatest work.

You can’t say that The War Of The Worlds doesn’t get you revved up and ready for excitement. Images from the two world wars with dramatic narration conclude with the words “And now, fought with the terrible weapons of super science, The War Of The Worlds”, leading into the credits, after which Cedric Hardwicke speaks a variation of the introductory words spoken by Welles in 1938, adapted from the novel [of course for me most implanted in my mind is Richard Burton’s version from the Wayne album]. “No one would have believed in the middle of the 2oth century that human affairs were being watched heavily and closely” intones Hardwicke, then a new bit is added so we can get matte paintings – with glass employed to create depth – of the planets [though oddly not Venus] and be told why these worlds would be unsuitable for the Martians. I watched the film on a recently bought Australian Blu-day from Imprint, as it was much cheaper than the other ones; however there’s a curious mistake in the colouring of Mars which is now more blue than red. Apparently not all releases contain this oddity. The meteorite that lands by Santa Rose is the first to land; some townsfolk are outside a cinema showing Samson And Delilah which must be a tribute to poor De Mille who tried to film this for ages. The scenes with the meteorite are absolutely brimming with suspense as more and more people gather and more and more things happen, and the pacing is just right, things moving along but definitely allowing for anticipation to build. Having our hero and a fellow scientist fishing nearby might be a weak coincidence; Pal could surely have thought up a better way to get Forrester into the action early? Yet the first encounter between him and Sylvia is amusing with her not realising he’s who he is, and there’s no time for boring romance thereafter [in screenwriter Barrie Lyndon’s first draft, they were already engaged], though as per the times she’s mostly regulated to serving coffee and cakes to soldiers, falling asleep and praying.

There’s a brief retreat to a square dance where everyone’s drinking coke [because of a clause in Anne Robinson’s contract which forbade her to drink or promote alcohol], but no sooner do we cut to there when lights go off and watches stop and become magnetic, while at the site there’s some definite unscrewing at the top of the meteorite and a snake-like mechanical object comes out and looks around for what seems like ages. What a tense scene this is, eventually relieved when a ray emits from the machine to turn the three humans present into white dust. The army soon arrive and anxiety is increased by reports like this one“Once they begin to move, no more news comes out of that area”. A plane drops a bomb and in the smoke we can see three manta ray-like war machines scarily rise. There are two interesting things about this scene. Firstly, wires were very visible in previous versions of the film I’d seen, though original cinema prints had them almost, if not quite, obscured, because for fifty years, from the late ’60s when 3-strip Technicolor prints were replaced by the easier-to-use and less expensive Eastman Color stock, the lighting, timing, and image resolution deteriorated and flaws in the special effects became increasingly visible. The Blu-ray has the wires obscured. And secondly, you can see three electronic beams underneath the machines which never appear again. Pal initially planned to have the machines be tripods as in the novel but, after being told by an army technical adviser that such things would pose little threat to ’50s military, he opted to change them but still have them to walk on visible electronic beams until, after the first two shots, it was noticed that having electronic sparks emanate from the holes at the bottom of the machine could become a major fire hazard. The cast remained under the impression that they were dealing with tripods, and the line “There’s a machine standing outside alongside us” was kept in, a curious oversight.

Nonetheless the machines look hugely impressive, even if their second, green ray is a disappointing replacement for the chemical black smoke of the novel; I don’t know why they didn’t have that. But the disintegrating, using 144 matte paintings to create, looks really impressive, as does the impenetrable force field that appears during the battle, which resembles, when briefly visible between explosions, a glass jar. This was accomplished with simple matte paintings on clear glass, which were then photographed and combined with other effects, and optically printed together during post-production. The elongated snake-like thing with a camera looking for our hero and heroine is extremely menacing, but the alien? Hmmm. The briefly glimpsed pink blobby humanoid with wavy arms running about outside works okay because the shot is so quick; the first time we watch the film, we’re not sure what we’ve seen. Then it comes inside the house, glimpsed as a misshapen shadow in a great few seconds which belong in a horror movie. Tapped on the shoulder, Sylvia turns around and sees – well – a slightly pitiful being that does look commendably extra-terrestrial but hardly inspires fear or awe. However, it’s certainly weird, with its crab-like arms, machine-like face just like the one on the camera [so are these creatures part mechanical?], which helps. A scene not long before did have Forrester who, in typical ’50s sci-fi style, is everywhere, hypothosise that “Physically, they must be very primitive”. The scene where Forrester and Sylvia are trapped in a house by three machines [and the only scene in this film which suggests that the Martians may want humans for something other than pure extermination, unlike the book, album and 2002 remake] is tremendous otherwise. And the Martian arm which crawls out of the first war machine which crashes due to – well come on, you know the story even if you haven’t seen this particular version of it – the earthly virus taking effect, is very effective.

The battle sequence includes real military footage well cut in. Less successful is a narrated montage of global destruction which includes black and white footage and real disaster shots, though it may have seemed fine to many 1953 cinemagoers and even provided some immediacy, despite the same building being shown falling down three times. A sense of no hope does increase. Blood from the killed Martian and a severed camera provide insight, leading to a scene where the Martian’s perspective is somehow viewed on a TV screen which may have inspired an even more outlandish one in Quatermass And The Pit. But the scientific equipment that might produce a weapon is destroyed in a riot, and even an atomic bomb does nothing. There’s a moving, if quick, shot of a small boy sitting on his own sucking a lollipop while everyone around him is evacuating the city. The big destruction of Los Angeles is spectacular, but gives the impression that the Martians, who seem to do everything in threes, are rather inefficient and stupid seeing as nearly everyone has left for the nearby hills just outside. Surely they’d be better off wasting all the humans first, especially seeing as they all seem to be gathered in one vulnerable area? The climax of Forrester running from church to church as everything is being blasted to smithereens around him is a bit goofy. Why is he doing this? Because Sylvia once hid in a church as a kid, which brings me to my major issue with this film. Welles was a staunch atheist who hated religion and in his book included a cowardly and uninspiring Curate, whom the narrator regards with disgust. Yet here we have the sympathetic and heroic Pastor Collins who dies a martyr’s death early on, while the finale strongly emphasises the Divine nature of Humanity’s deliverance. What an insult to Wells. Though, for the sake of balance, I must mention that Wells did mention God in the very final line of his book – though I’ve always thought that it had been intended ironically!

In any case, I don’t want to end this review with strong negativity. It’s still a pretty cracking show. The characters are thinly written but do they need to be rich? Lee Marvin was originally considered for the lead Gene Barry role. How wrong that would have been, despite Marvin being a good actor and Barry being just an average one. The sets are very obvious to our modern eyes but the vibrant colour, finally looking as it should do [well, except for Mars in my edition] on Blu-ray, is gorgeous, especially good use being made of the green and red of the Martian’s rays. The barrage of sound effects is immensely effective; they turned up in many TV programmes including The Outer Limits, Star Trek and Star Trek: The Nect Generation, and overshadow Leith Steven’s surprisingly [especially for the time] sparse – but dramatic when it needs to be – music score. Lacking much in the way of subtext the way many sci-fi films of its period do, except for a Cold War fear of enemy invaders who have much better weapons than we do, it more than gets by on sheer punchiness and showmanship.

Rating:

Be the first to comment